The steps of the Dr. John Mason Boyd memorial arch at the corner of Gay Street and Main Street offer a fine perch to ponder bygone times in this old section of downtown. Anyone who has more than just glanced over at the Knox County Courthouse and its lawn scattered with various monuments knows there is deep history on this southwest corner. For the most part, we’ll let “Our Beloved Physician, Dr. John Mason Boyd” be our guide for this story.

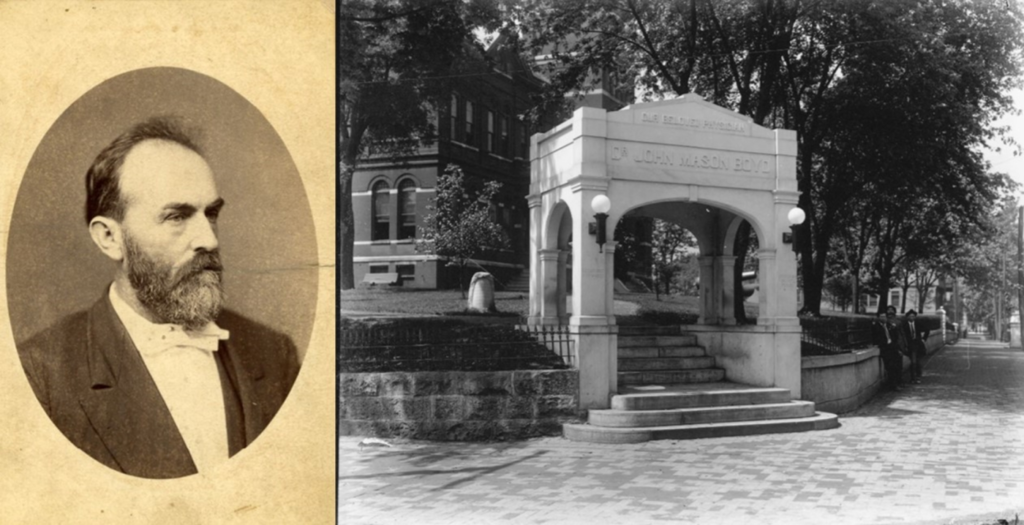

These words form the main inscription on the monument, the doctor’s birth and death dates (1833-1909) are inscribed on the left-hand pillar, while on the right, “Erected by a grateful public.”

This arch, made of white marble, was paid for by public donations (all the donors were women) to memorialize Dr. Boyd, who enjoyed a long and respectable career. He studied medicine here, in New York and Philadelphia and later abroad in France, Germany and England.

Dr. John Mason Boyd and the memorial arch, circa 1915, when it was still quite new. Photo courtesy of the McClung Historical Collection.

Boyd was known in his early days as a “horse and buggy” doctor, riding around on a bay horse. Before the Civil War he began to specialize in the field of obstetrics and in his early 20s he assisted the renowned Dr. William Baker, who performed the first hysterectomy, anywhere in the nation, on a Black woman named Matilda. (See story and podcast links below.) During that war, he acted as a surgeon for the Confederate army.

Dr. Boyd’s father was Judge Samuel Beckett Boyd (1806-1851), who served as Knoxville mayor for four years beginning in 1847. His sister, Sue Boyd Barton gained some local status as a soprano, known as “Knoxville’s Jenny Lind,” and for her short-lived courtship of Union Gen. William Sanders, who was killed during the Siege of Knoxville in 1863. His cousin was none other than Belle Boyd, the Confederate Civil War spy, who sought safety with the Boyd family during the conflict.

The location of the memorial arch, completed two years after his death, appears to be based on earlier comments by Boyd himself about his fond memories of the place when he ran around barefooted as a young child.

Perhaps he enjoyed some playtime here while his father performed judicial duties in the old Knox County Courthouse when it stood right across the street near the northwest corner of Gay and Main. At that time the Boyds were living just around the corner in the circa 1792 frame house built by Gov. William and Mary Blount. While it hasn’t always been cherished, what we know today as Blount Mansion was for many years a ramshackle old home, especially around the time that the arch was completed, and often just called the “Boyd Place.”

Although John Mason Boyd grew up in Blount’s old house, he was actually born in the home of Knoxville’s other founding father, Capt. James White, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, who settled here in 1786 before anyone else. Together, Blount and White founded the town in 1791. But in 1833, when Mason was born, White’s original log cabin (one of several structures that comprised his frontier stockade) was then incorporated into the James Kennedy home on State Street. If it was in its original place today, the Kennedy house, and White’s Fort before it, would be just north of the First Presbyterian churchyard, in the vicinity of the northern end of the State Street Garage.

When young John was playing around Gay and Main in the late 1830s, Knoxville was still little more than a small, dusty town, perhaps still smarting from the fact that it had lost its original status as the administrative capital of Tennessee. (After Knoxville, the capital moved to Murfreesboro and then Nashville.) There is nothing showy downtown that commemorates Knoxville’s status as the capital marking, except a small stone monument on the courthouse lawn opposite the Andrew Johnson Building. It’s a memorial probably better known to tourists than locals.

By the late 1830s, here would have been a cluster of buildings on the corner of Gay and Main, likely a combination of private houses, hotels, and taverns. We get a sense of these buildings in the classic 1865 panoramic photograph of Knoxville, which continues to offer more clues about early Knoxville every time we look at it.

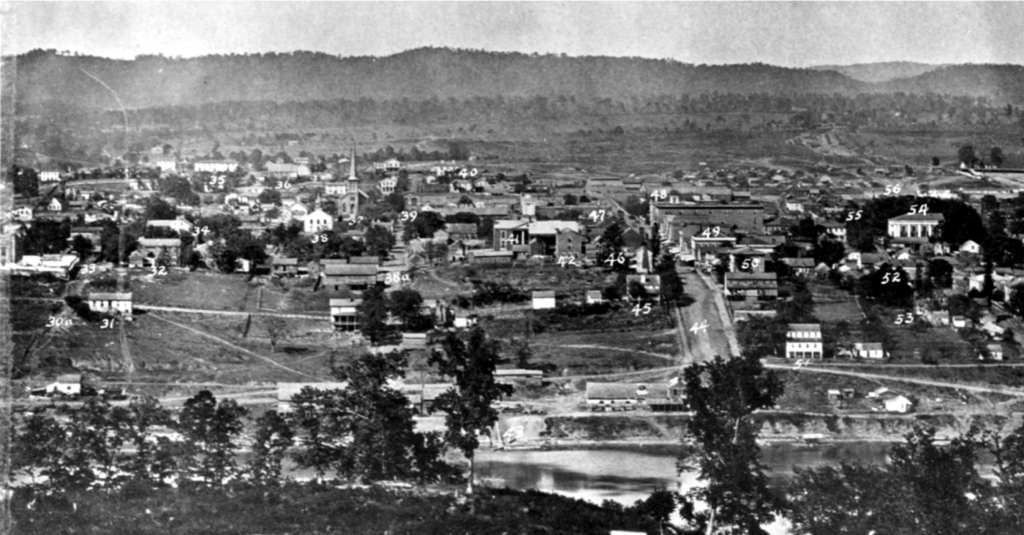

Part 3 of a four-part panoramic photograph of Knoxville, 1865. Photo courtesy of the McClung Historical Collection.

Identified in the center of the marked-up photograph as #46, on this corner, is the home of Matthew Nelson, who served as a state treasurer for the region and as a city alderman from 1817 to 1821.

The old courthouse is labeled #41 while #42 is the Mansion House, just to the west of the Nelson home. Formerly Mynatt’s Hotel, later the Franklin House, the Mansion House was run for a time by James Williams (likely the city alderman who served from 1839 to 1840). Citing poor health, Williams offered the house for rent in 1840, and described it thus:

“The mechanical execution of the building which is three and a half stories in height is of a superior kind, and the arrangement of the rooms is admirably adapted to the purposes of a hotel. The house is well supplied with furniture…the stables and outbuildings are large and commodious…”

Suitably equipped, the Mansion House was positioned to provide handy lodgings for a traveler, particularly one who had duties at the courthouse, and needed a bed and a meal for the night, and stable for their horse.

By the way, according to Presbyterian minister Rev. James Park (1822-1912), whose father of the same name was a two-time Knoxville mayor, wrote in 1910 that the Boyds had a tavern on Gay Street, up just past the Lamar House on the northwest corner of Gay and Cumberland. Built by John’s grandfather, Capt. John Boyd, about 1820, it was gone 16 years later when our young John was only three.

What’s fascinating is that behind Nelson’s home and the Mansion House is an open field and two other open lots overlooking the river. This is likely where young John played as a child while his father was at the courthouse. This was the former site of the Federal Blockhouse, built in 1793 to offer the fledging territorial capital some military protection, although reports of drunken soldiers, often not paying their store bills, led to some mixed feelings about it at the time.

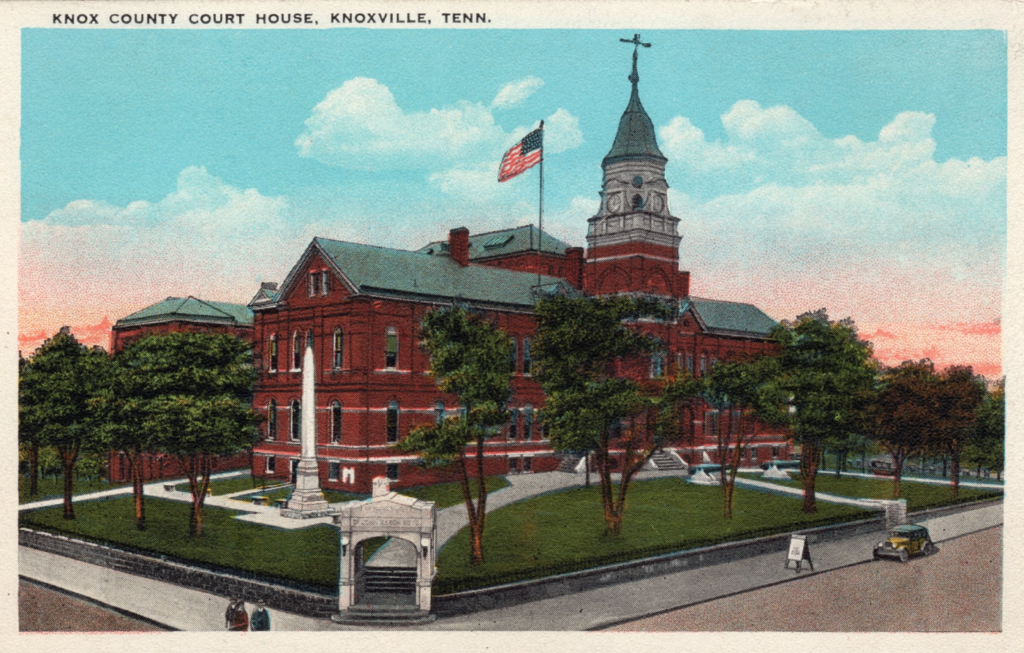

When John was nine in 1842, construction was completed on the third courthouse on the north side of Main Street, which lasted 42 years until a newer one (the fourth and present one) began to be built on the south side of Main in 1884. It was later enlarged with two wings added around 1919.

Several memorial monuments on the present courthouse lawn continue to serve as reminders of those frontier days, and frontier hero John Sevier (1745-1815), aka Nolichucky Jack, who, living in Knoxville, on and off, was asked to serve as the first Governor of the state when it was formed in 1796. He didn’t get very far building a house here—perhaps just a foundation—and then sold it to James Park, the elder, who built what we know as the Park House on old Crooked Street at Walnut and Cumberland.

A view of the expanded Knox County Courthouse as we know it today, with the Sevier monument behind the memorial arch. Source: Alec Riedl Knoxville Postcard Collection/KHP.

It’s been said that the larger-than-life Sevier had a genuine way with people, but almost 75 years after he died there would have been only a few souls in Knoxville who might have remembered seeing him in person when they were young. Still, in 1889 a mind-boggling crowd of 30,000 people showed up to pay their respects and witness the reinterment of his remains that had been found in the wilderness of Alabama.

Sevier’s wives are also memorialized here on large stones standing either side of the giant Sevier obelisk. His first wife, Sarah Hawkins (1746-1780), died before the days of Knoxville, but his second wife, Katherine “Bonny Kate” Sherill Sevier (1754-1836) was revered in her own way. Her name can be found on streets and schools in South Knoxville.

***

As Dr. Boyd passed middle age he would have seen new buildings replace older ones along Gay Street. From the corner of Hill Avenue, four Victorian houses were built in a row, followed by an alley, then another house and a commercial building that in the late 1800s operated as a marble shop on the southeast corner of Gay and Main. In old postcards, the block looks like an inviting, stylish place to live. On the corner of Hill, the house with a rounded turret was owned for a good while by the Atkins family, notably by C.B. Atkin (1864-1931), the wealthy mantel maker and owner of the Atkin House Hotel at the northern end of Gay Street by the railroad station. Next door to him was the respected photographer Joseph Knaffl, whose studio was just up Gay Street, too.

The 900 block of Gay Street between Hill Avenue and Main Street, early 1900s. Source: Alec Riedl Knoxville Postcard Collection/KHP.

All of these homes were demolished (with the exception of the front of the Knaffl house, which was moved to Burlington and incorporated into another house on Speedway Circle) to make way for the Tennessee Terrace Hotel, which broke ground in late 1925. In the following photograph, to the right of the demolished Gay Street block, you can see the row of houses on the south side of Hill Avenue. Just visible, set back a little, is a fifth building – that’s Blount Mansion, probably around the time that it was slated for demolition to make room for a parking lot for the new hotel. In 1925, the forward-thinking preservationist Mary Boyce Temple would write a $100 check as a down payment to save the structure and set in place plans to save it as a historic museum. By the late 1920s, the Tennessee Terrace was given a new name, the Andrew Johnson Hotel.

But between the demolition of these houses and the erection of the hotel, it would have been the only time that there was a clear line of sight between Dr. John Mason Boyd’s memorial arch and the Blount home where he grew up.

The demolished 900 block of Gay Street, close to East Hill Avenue, during the early stages of construction of the Tennessee Terrace Hotel, circa 1926. Photo courtesy of the McClung Historical Collection.

For more on Dr. John Mason Boyd, read Jack Neely’s story, “Matilda X,” here or listen to a podcast of the story on Knoxville Chronicles.

“Ghost Walking” is my own take on life on the city’s streets in bygone times; how these streets and their buildings have changed through the years, and how through old pictures and stories we can glimpse the echoes of people’s past lives and particular events. If you’re looking for spooky ghost stories, please allow me to direct you to historian Laura Still’s book, A Haunted History of Knoxville, and her “Shadow Side” walking tours. Laura has been leading historic walking tours for years and she also generously donates a portion from most of her tours to the Knoxville History Project. Learn more about the city’s history and culture at Knoxville History Project. ~P.J.

Leave a reply