The doctors and patient who pioneered a new surgery on Gay Street

If you browse around 19th-century graveyards as much as we do, and do some quick math, you’ll find an alarming number of untimely deaths of young married women. Many of them died in childbirth, or of disorders of reproductive organs. We see fewer of those untimely deaths today because of advances in medical science that include one radical bit of surgery called the hysterectomy.

One Knoxville doctor, with assistance from a few others including his suffering patient, hurried medical science along a bit, perhaps right in his office on Gay Street. It happened 165 years ago this month.

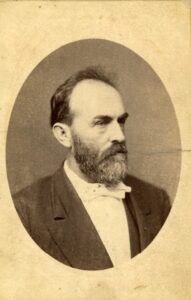

Born in Kentucky in 1800, William J. Baker was a graduate of venerable Transylvania University. He came to Knoxville around 1825, for reasons that may have been hard to explain to his family and friends. There wasn’t much going on here. When he arrived, the former capital didn’t have either railroad or steamboat access, and the rough-edged riverbluff town was commencing a decades-long period of doldrums.

His was a family of doctors. One brother, Leonidas, joined him in his practice for a while before—perhaps wisely—returning to Kentucky. A much-younger brother, James Harvey Baker migrated down here too, and stayed.

William married a local woman, Mary Ann Cox. They never had any children of their own, in an era when nearly everyone who could have children did have children, often as many as a dozen of them. But for some couples, it just didn’t happen. We can only guess whether that fact influenced Baker’s interest in gynecology. He developed a reputation as a diagnostician and as a skilled lithotomist—a remover of stones from places they weren’t supposed to be—and for gynecological surgery.

In his early Knoxville years, Baker lived on the downtown end of Cumberland Avenue, but the Bakers’ home as later remembered was on Gay Street between Clinch and Church—the same block that now includes the Tennessee Theatre and the History Center. It also included his office and operating room.

A younger doctor later described Baker as a “large, rather portly, dignified, cultured gentleman, with a red complexion, so flagrantly noticeable that strangers invariably attributed it to excessive use of one of the three products for which even at that early date his native state was famous, but they would be entirely mistaken, for the doctor was religiously temperate.”

We can guess at two of the products alluded to: bourbon and tobacco, perhaps—but beyond that, Kentucky was also known for corn moonshine, rye whiskey—and hemp. In any case, it sounds as if Baker didn’t indulge in any of them.

He was probably still considered a newcomer in 1830, when he was one of five charter members of the first Tennessee state medical association. (The all-Knoxville group boasted two future mayors, including Scottish immigrant and University of Edinburgh trained Donald McIntosh.) They faced a big challenge in 1833, with the state’s first cholera epidemic. Dr. Baker was later one of the founders of the Knox County Board of Health and the East Tennessee Medical Society. In 1853, he led an effort to build a hospital in Knoxville, obtaining land for it apparently around what’s now Caswell Park. Slow to gain funding, it was delayed by war; Baker didn’t live to see it develop.

Community-minded outside of the medical profession, Dr. Baker was a member of a county commission working on plans to repair or replace the aging courthouse, and served as a trustee of East Tennessee College—not long after that forerunner of UT had established its campus on the Hill.

Dr. Baker himself was a complicated fellow. In 1834, when he was still a young man, he had been a leader of a Knoxville-based emancipation movement called Friends of the Abolition of Slavery. He signed a public document that declared slavery to be “MORALLY, POLITICALLY, AND ECONOMICALLY WRONG”—they chose to emphasize that phrase with capital letters. The anti-slavery cadre proposed a “system of abolition” through the new state constitutional convention, declaring every child born into slavery beginning in 1835 to be free.

By some accounts, that early anti-slavery movement was led mostly by slaveholders, including Baker himself. That probably seems more hypocritical today than it did then.

East Tennessee abolitionism was a wave that crested and collapsed. The writers of the new state constitution in Nashville ignored the Knoxville committee’s plea, and the new Constitution did nothing to end slavery, gradually or otherwise. In fact, it imposed new limits on free people of color, denying Black men the right to vote.

One of the perplexing realities of that era is that so many idealistic young abolitionists, with age, lost faith in an ideal that might have made them seem heroic to future generations. Public abolitionism in Knoxville evaporated. In fact, Dr. Baker and his allies drew criticism two decades later for having opposed slavery.

Meanwhile in those complicated times, Dr. Baker remained a slaveholder. In 1844, the physician advertised for help finding a runaway, Shadrach Henderson, “a bright mulatto boy between 19 and 20 years of age” who “can read pretty well and is a tolerable barber.”

In his political sympathies, Baker was known to be a Whig, an opponent of President Jackson and his legacy. He had publicly supported William Henry Harrison in 1840, endorsing a Fourth of July rally for the Ohio Whig hero that year. (Young Abraham Lincoln supported the same fellow, who enjoyed his victory only briefly. He’s the president who died one month after he was inaugurated.)

By 1851, some allies were sufficiently impressed with Dr. Baker to propose him as a candidate for U.S. Congress. He responded decisively in Brownlow’s Knoxville Whig: “I cannot now merge the Doctor in the Politician…. Absolutely discarding all congressional and other political aspirations, I announce myself now, as uniformly heretofore, devoted to medical practice. In this profession of my early selection and long experience, I feel that I may still be useful.”

As it happened, Knoxville may have proved to be a good investment for Dr. Baker. Thirty years after his arrival, he was still downtown, but by 1856 it was an altogether different place. The railroad had finally arrived, factories followed quickly, and Knoxville was suddenly a crowded place. The town now had a capacious market square, and the streets, some of them paved, had gas lights.

Despite the esteem with which he was held, Dr. Baker might be forgotten if not for one remarkable case, that of an African American woman named Matilda.

It’s impossible to contemplate the image of white doctors working on an African American patient without acknowledging that it took place in an unequal society where slavery was still legal, and most members of one race were not often free to make their own choices. Interracial surgery has a troubled history, with credible charges that some white surgeons used enslaved patients for experimentation—and, even generations later, that women of color were subjected to hysterectomies when less extreme solutions were available. Medical professionals who have studied the records of this case do not believe that to have been the case with Dr. Baker and Matilda.

Matilda presented herself at Dr. Baker’s office in June, 1856. She’d been suffering from chronic uterine inflammations for five years. A married young woman, she had been pregnant the year before, but miscarried. She thought she was pregnant again—there was a large, hard thing in her abdomen—but she sensed something was wrong.

Matilda was described as a “a negress, a servant.” The word “slave” doesn’t appear in the doctors’ descriptions of her. She was married, and in some states that might imply that she was a free person of color; most states did not permit the enslaved to marry, but Tennessee was a rare state that did.

She was a subject of an operation, and as is often the case today, the full name of a patient of any race is not often revealed in medical reports. That may have been the decent practice, but it also makes it hard on historians who are trying to find out what they can about her life.

One rare clue is the name of her employer, who was an especially interesting woman. Matilda was described as a servant of Laura Bearden. Originally from Connecticut, she was the young widow of Marcus DeLafayette Bearden. A major figure in antebellum Knoxville, he was a wholesale grocer who became a pioneer in steamboating and one of the two guys who built the papermill for which Papermill Road is still named. Laura was his third wife, and the only one who outlived him. Laura later married a Unionist lumber-products executive named David R. Richardson.

Several researchers we’ve conferred with—Kevin Bogle at UT, Danette Welch at McClung Collection, and Janine Winfrey at the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, note that the census “slave schedules” of 1850 and 1860 list Bearden and then Richardson owning an unnamed young woman—perhaps inherited by Laura, then acquired through marriage by her second husband. The census didn’t list enslaved people by name, but it’s a strong guess that Matilda was not a free woman at the time of her medical crisis, but that she was the African American woman known after the war as Matilda Bearden.

For what it’s worth, Laura Richardson, who likely inherited Matilda upon her husband’s death in 1854, and regarded her as a servant in 1856, is a remarkable woman, herself. She’s remembered in some national sources for something else: an innovation that changed how Americans celebrate a holiday. But that’s years down the road.

***

Dr. Baker examined Matilda, observing that her appearance was that of a woman was indeed about seven months pregnant. But she wasn’t.

Just to figure out what her problem was, he would have to operate, and he couldn’t do this one by himself. He assembled a team of doctors he knew well. Dr. Baker’s three assistants at the operating table are interesting. All of them were young men compared to Dr. Baker. Dr. James Rodgers was around 38. He was an alumnus of the Hill, when it was known as East Tennessee University, and like Dr. Baker, he’d also studied at Transylvania. He was an obstetric specialist with an office on East Main. At a time when Knoxville, including its medical community, were dividing politically, Rodgers was destined to be a Unionist.

A younger partner of Dr. Rodgers was Dr. James H. Sawyers, who was married to fiercely pro-Union editor Parson Brownlow’s eldest daughter, Susan. We don’t know much more about him except that he contributed several articles to a regional medical journal. He was only 24, but he reportedly died in 1857, just months after the operation he assisted.

Of that historic team of four surgeons, the youngest is the one best remembered today. If you walk around downtown much, that final name may ring a bell, even if you don’t remember right away where you’ve seen it. It’s the name of “Our Beloved Physician,” memorialized with the stout marble arch at the courthouse corner of Gay and Main. At 23, Dr. John Mason Boyd was the youngest of the team.

Son of a judge, Boyd had been born downtown, in the cobbled-together Kennedy house off State Street that included, almost unrecognizably, James White’s 1786 log cabin. He was another alumnus of the pre-UT Hill, and studied medicine at the University of Louisville, then the University of Pennsylvania, from which he had graduated earlier in the year. Like most of the Boyds, including his cousin, the spy Belle Boyd, he would soon be leaning toward the secessionists, serving the Confederate army as a surgeon.

That was all in the future. In 1856, Dr. Boyd was Dr. Baker’s young partner in the Gay Street office.

***

Hysterectomies were not completely unknown in 1856. One had been attempted in Charleston in 1846, but the patient died five days later. A partial hysterectomy of one ovary, in Lowell, Mass., in 1853, was a success, although much of what happened on the operating table was not planned. Another hysterectomy, the removal of the uterus, took place in the same city, the same year, by another doctor—but without an oophorectomy, the removal of the ovaries.

Like much surgery, it was uncharted territory, and dangerous to the patient. Young Dr. Boyd wrote up the detailed report about exactly what they accomplished. “It was determined to operate the following Thursday, Nov. 13,” he wrote. “At 10:00 a.m., Drs. Rodgers and Sawyers kindly assisting, the patient was anaesthetized. Chloric ether was administered by Dr. Sawyers in the outset, but its action was very tardy, and chloroform was substituted.” He goes on to describe the patients’ enormous tumor and malfunctioning organs to which it was attached. It sounds as if they did much more than they expected to. She was sutured up when they were done, and watched with uncertainty to see how the patient would respond.

Matilda was up and down for about seven weeks, occasionally bleeding, sometimes in severe pain. But after seven weeks, she was “free from uneasiness,” as well as from most of her symptoms. She was finally discharged on Jan. 3, 1857.

The surgery was mentioned in the local papers the following month, and an account of the operation was a last-minute addition to The Southern Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences.

Her surviving doctors presumably kept track of her. By the 20th century, a few references note that Matilda lived for another 34 years.

The operation has been referred to, rather vaguely, in Knoxville histories for years, but usually just as a little “how-about-that” detail in the lives of the doctors who performed it. In the biographical sketch of Dr. Baker in the 1946 volume, The French Broad-Holston Country, notes, “As a surgeon, his most notable operation—a hysterectomy—was performed … upon a woman who lived for 34 years thereafter …. It is claimed that this was the third such operation known to medical science.”

Others strongly suggest it was the very first—at least the first successful one, with the patient surviving long enough to appreciate life after a hysterectomy.

In an internationally published 1949 book called Gynaecological Surgery and Instruments, medical historian James V. Ricci reported that “A remarkable operation for a uterine tumor was performed by William J. Baker of Knoxville, Tenn., on Nov. 13, 1856.” He follows with an extensive quote from Boyd’s account, letting his medical description speak for itself.

But the landmark surgery has remained little recognized. Some modern historians have gone a bit further with claims of the 1856 Gay Street surgery as America’s first successful hysterectomy. A 2006 issue of the medical journal Obstetrics and Gynecology ran an article by physicians Jason J. and Don J. Hall of the University of Texas Medical Center. It’s titled “The Forgotten Hysterectomy: The First Successful Abdominal Hysterectomy and Bilateral Salpingo-Oopherectomy in the United States.” Dr. Don J. Hall now practices here in Knoxville, specializing in gynecological oncology.

Less than two years after the operation, Dr. Baker retired at age 58, and moved to a brick house on Kingston Pike, in the Cedar Springs area, near where his brother Harvey Baker, another aging physician, lived. His former partner, Dr. John M. Boyd, took over his practice.

He would have witnessed the skirmishing associated with the approach of the Confederate army in 1863, and it was during that period that his brother Harvey was killed in his home by rogue Union troops.

Dr. W.J. Baker was an elder at First Presbyterian Church, which is sometimes cited as a reason his nephew, Abner Baker, is buried at the old churchyard on State Street. Son of Dr. Harvey Baker, Abner Baker was former Confederate soldier who was lynched from a tree on Hill Avenue in September, 1865, for killing a former Unionist on the courthouse lawn. Several years before the war, the old churchyard had been closed to new burials, but they made an exception.

Dr. Baker himself died just 16 days after his nephew did. It was an odd coincidence without a handy explanation. He’s buried at Old Gray.

Dr. Rodgers, the most obvious Unionist on the team, wore several hats in his postwar career, working as a physician but also president of the short-lived Knoxville and Charlotte Railroad project, and owner of a downtown drugstore. He was appointed by President Grant to be Knoxville’s postmaster. He died at 80 in 1898.

Today, the marble porte-cochere-like monument to Baker’s closest associate, John Mason Boyd, “Our Beloved Physician” probably honors his half-century as a local doctor. Dr. Boyd was remarkable for treating patients without expectation of remuneration, and for his courage in the face of deadly epidemics. He would go into the homes of victims of cholera and yellow fever, but never got ill, himself.

Boyd, the last surviving member of the surgical team of 1856, died in May, 1909. Obituaries, written by people who remembered Boyd in his last half-century years as a selfless physician, mentioned little about either the Civil War or his role in the historical hysterectomy. He was buried at Old Gray, with mourners of both races in attendance. The same month that he died, an effort led entirely by women formed the John M. Boyd Memorial Association. Two years later, they erected a marble arch at the corner of Main and Gay.

***

Except for the obscure and short-lived Dr. Sawyers, it’s easy to learn the destinies of the white surgeons who were there that morning in 1856. Naturally, we want to know what became of their patient.

Much of what we might ascertain about the rest of Matilda’s life is educated guesswork. We don’t know with certainty what became of her. It’s not impossible that she left town. But research strongly suggests that she stayed, and that her middle age might have been better than that of most African American women of her era, before it took a tragic turn.

McClung Collection researcher Danette Welch found records that a Black woman named Matilda Bearden married in 1866, to a man named Archy Karns, who was a teamster—a driver of horsedrawn wagons.

When her profession was listed, Matilda Karns–or Matilda Carnes, as she’s listed in the 1880s, assuming she’s the same person, was listed as a “domestic.” Did she remain in the employ of Laura Richardson, and stay with her household? That would not have been unusual. Unionists during the war, the Richardsons moved to the North for safety, but returned to Knoxville when it was over. David Richardson was for a time a partner of Connecticut-born George Burr in his major architectural lumber mill, along the tracks in what we now know as the Old City. They lived at the corner of West Vine and Prince (later Market), on the hill barely north of what’s now TVA headquarters.

By the time David died in 1870, Laura Richardson was active in a Union women’s auxiliary. It was in that role that she would claim a modicum of national fame. Laura Richardson has been credited with introducing the idea of planting miniature U.S. flags in National Cemeteries on Memorial Day, or Decoration Day, as it was known in her time.

Previously, it was common to strew flowers on soldiers’ graves. Unsatisfied with the flower harvest, she had a brainstorm when she was walking by a fabric store downtown. Inside were bolts of fabric printed with American flags. She asked her former husband’s sawmill for help, and they obliged with some 3,500 little sticks. With her allies, she prepared 3,500 little flags suitable for planting.

National Cemetery, circa 1915 showing flags placed at each grave-a tradition that may have been started in Knoxville by Laura Richardson. (McClung Historical Collection.)

We don’t know whether Matilda was still working with Laura at that time, but it’s certainly possible that she was one of the women stitching flags onto sticks to plant at the National Cemetery, where Union soldiers of both races were buried.

Laura Richardson remained a Knoxvillian until about 1902, when in her 70s, she moved to Massachusetts to be near the family she had known in her youth.

***

By the late 1870s, Matilda Carnes was widowed and living alone on Crozier Street, later known as South Central, just as the rough-edged neighborhood was becoming known as the Bowery. She lived just north of Union Avenue, on the same block as the Black public school, Austin High, about 40 other modest households, mixed-race but mostly Black, and at least one saloon.

In the 1880 census, she’s living there with a 13-year-old niece named Rosa Alexander. Matilda was at least modestly a landowner, an unusual status for a Black woman in the 19th century, and that may have been her undoing.

In 1882, Matilda Carnes was one of the nine incorporators of the Daughters of Zion, “a benevolent organization, originated among the colored women of the town, for mutual benevolent purposes.” That was likely been a high point in her life.

Industrializing, fast-growing Knoxville was a little different from many cities. In Matilda’s middle age, African Americans were represented on City Council and on the police force and fire department. Her Knoxville included a respected college for the emancipated, and a growing parallel African American culture, with its own churches, festivals, ball games, and bands. The city might have offered something that made her extra years seem worth the living. But the proud, booming city, where fortunes were made and lost in a moment, had a dark and sometimes vicious undercurrent, perhaps most obvious in the murder rate, which was several times what it is today. People of both races killed each other, often with what seems like minor cause.

In Matilda’s household in particular, something went wrong. The childless widow sometimes took in other younger relatives, and around 1888, her step-granddaughter moved in with her. Sometimes referred to as Matilda’s niece, Mary Carnes was apparently the natural granddaughter of Matilda’s late husband. Around 40 years younger than Matilda, she was about 19.

On a Sunday evening March, 1889, Matilda, who had been in good health at age 59, was found dead at her home. A coroner’s investigation into the fact that Matilda had died “very suddenly” led to an autopsy, which found that she had been a victim of arsenic poisoning. An investigation led to the arrest of her niece, Mary Carnes, who confessed. She had served Matilda Sunday dinner, with rat poison in her greens. The brand, “Rough on Rats,” was blamed for several poisoning murders and accidents in the Knoxville area. It was alleged that Mary Carnes “killed her aunt to get possession of her property.”

If Matilda Carnes is indeed the same person as the patient in the 1856 hysterectomy, as several researchers believe her to be, she died just shy of the 34 years she’s always been reputed to have lived after the operation—more like 32 years and four months. And it’s odd that those medical texts don’t include a footnote that she was murdered–and if she had not owned property, and been too trusting of her heirs, she might well have lived much longer than that.

Mary Carnes was convicted and sentenced to 12 years for second-degree murder. (Light sentences for murder in that era are repeatedly surprising.) She went to prison in Nashville.

In 1896, Gov. Peter Turney, a former Confederate colonel whose gubernatorial career is known for prison reform, commuted her sentence to nine years, without publicizing a reason.

Where Matilda is buried is unknown. Her own personal fortitude surely helped with the outcome of a historic case. Despite her untimely death, she outlived two of her four surgeons. In her lifetime, she was never publicly identified by her full name as the patient who survived a landmark operation. It’s unclear whether she or her peers ever knew the role she played in medical history.

By Jack Neely, October 2021

Leave a reply