Originally written by Paul James and published by Inside of Knoxville.

Have you ever noticed how quiet it is around Gay Street and Main Street in the evening? During the day, it’s reasonably lively with lawyers, bankers, government employees milling about. It will be even more so in the coming years after the redevelopment of the Andrew Johnson Building breathes more life back into this part of downtown. But in the evening, unless you’re looking for dinner at the Bistro or going to a show at the Bijou, this section has the appearance of a bit of a ghost town.

That’s because three large complexes take up a few acres around here: the Knox County Courthouse, the City-County Building, and the Howard Baker Jr. Federal Courthouse that occupies almost all of the long block between Gay and Walnut and Main and Cumberland. When the latter complex was originally planned by Chris Whittle as a new HQ for his publishing empire, it caused some controversy as the site cut off Market Street when it opened in 1991. Still, on most days you can walk through the open courtyard to reconnect with Market and head up to Market Square.

But as we’ve come to learn on these ghost walking rambles, there’s always a story or two from the past that can bring these rather unassuming places into a more interesting historical focus.

If you were standing on the sidewalk in 1906, right where the entrance to the courtyard is today, you would have been faced with two interesting places to visit. For almost a decade the Woman’s Building’s stood right here. Originally built for a destination about 200 miles away, that structure first served as the Knoxville Pavilion at the Tennessee State Centennial that ran in Nashville for six months in 1897. A coalition of Woman’s Clubs in Knoxville banded together to raise funds to dismantle the structure and transport it to Knoxville. Being made of wood, it would have been likely broken down into sections and brought here by train. It opened as the Woman’s Building in 1898.

An early 20th century postcard of the striking Woman’s Building on Main Street. (Alec Riedl Knoxville Postcard Collection/KHP.)

Organizers and members of City Council determined its location on Main Street at the intersection of Market Street (then called Prince Street, making an initially steep but straight shot from the river wharf to Market Square), where the old courthouse had once stood before the one we know today was built across the street, to the south, in 1885.

Once re-erected, the Woman’s Building became the city’s first permanent art institution. According to historian Laura Still in her book, A Fair Shake: The Leaders of the Fight for Women’s Right’s in Knoxville (Knoxville History Project, 2021), the building served as a home for “club meetings, banquets, classical music recitals, art studios, and museum exhibitions during the annual Fall Carnival. It served as the headquarters of the Ossoli Circle and the Knoxville Symphony Quartet, among others, and held numerous studios for artists and musicians. In the great hall, there were grand pianos, huge Italian mirrors, and on the ceiling a fresco of long, graceful mermaids in shades of green.”

Most but not all of those artists who kept studios there were women, including Harriet and Eleanor Wiley, sisters of impressionist painter of statewide renown, Catherine Wiley. Piano teacher Lou Krützsch had a studio here too (her brothers were soon to change their last name to Krutch, with Charles Edward Krutch later leaving a legacy gift to the City to establish Krutch Park in the mid-1980s.)

In lieu of paying rent for a small studio, Robert Lindsay Mason served as custodian of the building. A talented artist and writer, Mason grew up in East Tennessee and attended the University of Tennessee briefly before moving to Philadelphia where he studied with renowned illustrator Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute. An active member of the Nicholson Art League, in the 1920s he set up an art school at his own home on East Church Street, and in 1927 published one of the first books on the history and culture of what was fast becoming Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The first pressing of Lure of the Great Smokies sold out in less than 30 days. Few of Mason’s original works are known to exist today.

Like many wooden structures, the Woman’s Building didn’t last very long. The last day that anyone could have stood on the sidewalk and admired it would have been Christmas Eve in 1906. Early in the evening a fire began at the rear of the building and quickly took hold. Firemen were able to contain the blaze relatively quickly, but practically all the artistic treasures within, including works of art and ornate furniture, were completely consumed.

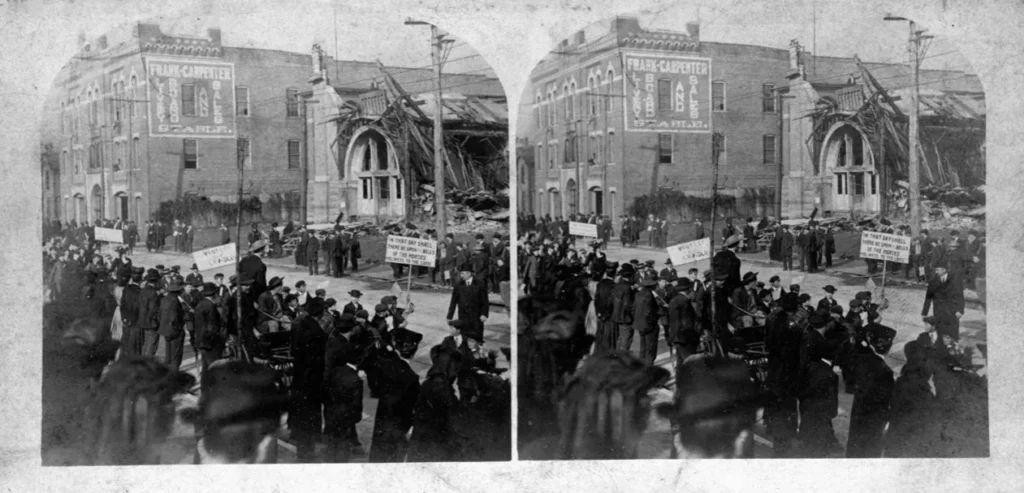

A stereographic photograph of a Temperance Parade in March 1907 (three months after the blaze) showing the charred remains of the Woman’s Building on Main Street. (McClung Historical Collection.)

Robert Lindsay Mason claimed that all was fine when he locked up the building that late afternoon and he had made sure that the furnace was out and electricity disconnected. In the aftermath, fire department officials declared that they were stumped about what actually caused the conflagration.

Mason’s janitor, an African American fellow with the curious name of Canary Curtis, suggested one clue. After finding remnants of a large firework rocket among the building’s charred remains, he proposed that a stray firework may have set the building alight. That’s plausible since raucous Christmas Eve celebrations were common in those days, when rowdy men set off fireworks indiscriminately around town amid general merriment, if not outright mayhem.

Rather than rebuild the structure, leaders of the Woman’s Building moved into an existing house around the corner on Walnut Street (then known as Crooked Street), across from the James Park House. That spot is now a staff parking lot for the downtown post office. After enlarging the house, the new artistic venue became known as The Lyceum.

Despite the 1906 fire, the buildings adjacent to the destroyed Woman’s Building were not harmed. Frank Carpenter’s Livery and Stables stood to the west, and to the east, near the corner of Gay Street stood the Auditorium Rink, which had opened 10 months before the blaze. Primarily a roller-skating rink, the Auditorium looked like a large arch-roofed building.

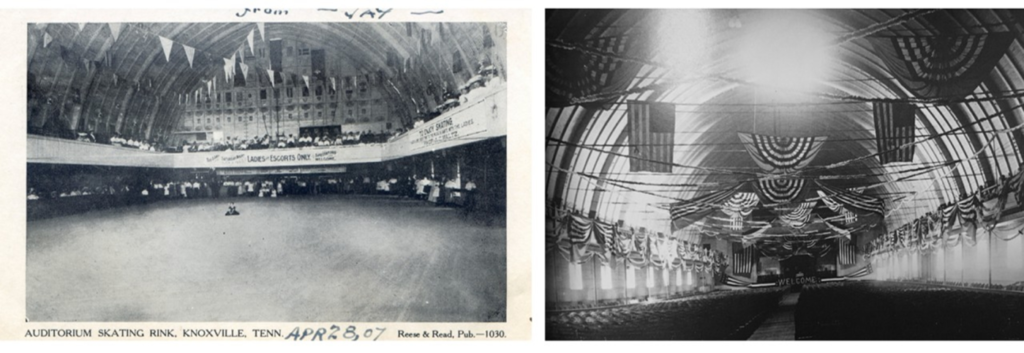

Two views of the interior of the Auditorium Rink: a rare postcard from 1907 and a patriotic display, possibly for President Taft’s visit in 1910. (Left: Merikay Waldvogel Postcard Collection/KHP. Right: McClung Historical Collection.)

For a short while at least, the rink proved to be a popular attraction for skaters. Contemporary ads proclaimed that “management guarantees that no objectionable characters will be permitted in the on the floor, and special attention will be shown ladies and children.”

Open daily for beginners in the morning and a short public session in the afternoon, the rink aimed to attract its largest audience during the evenings when military bands provided accompaniment. The facility also catered to “Roller Polo” teams for boys and girls, as well as basketball games on skates. The so-called “Champion Skater of the World,” Alfred C. Waltz, came here one time for a high-profile demonstration, as did a lesser-known one-legged skating wonder named Kilpatrick.

For a few months in 1910, skating took a short hiatus so the rink could accommodate the Journal & Tribune’s cooking school. But there were also more unusual attractions, including trick cyclists, pig races (whatever they were if not timed porcine competitions?), two-mile race-and-pie-eating contests, Halloween parties, and Masquerade balls—Little Red Riding Hood won first prize one year.

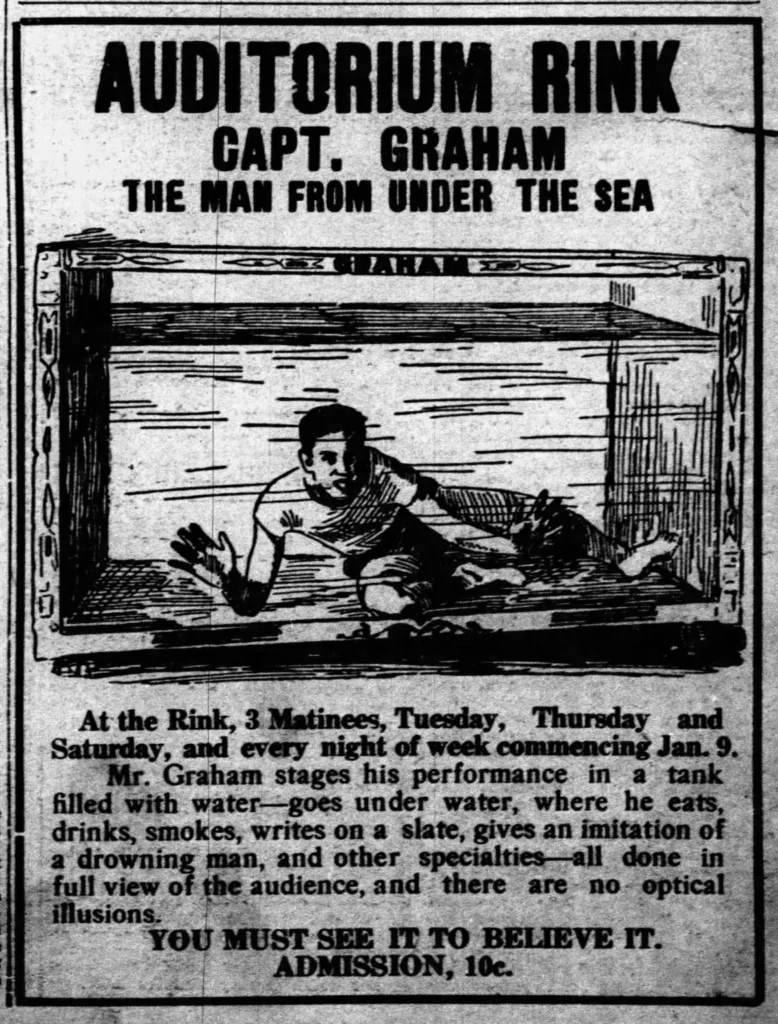

Even among these activities, weirder ones stood out. In 1911, Capt. Graham, the self-styled “Fish Man” performed here with his own show: “The Man from Under the Sea.” Inside a tank of water, Graham “eats, drinks, smokes, writes on a slate, gives an imitation of a drowning man, and other specialties.” It turned out that the Fish Man was a local who lived just up the street on Cumberland Avenue.

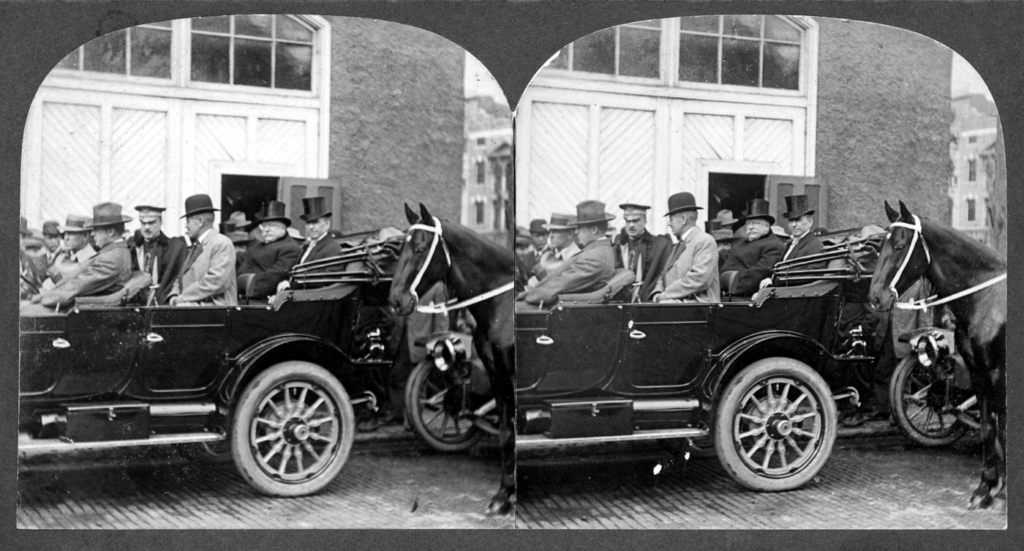

In contrast, the building also served more serious roles. President William Howard Taft came here in 1911 to address a biracial crowd for an hour as part of his visit to Knoxville that included a trip to the Appalachian Exposition held at Chilhowee Park. Arriving in the morning at the Southern Station on Depot Street, operators at the J. Allen Smith flour factory on Central Street blew a signal to surrounding factories that joined in with welcome whistles to herald Taft’s arrival. After visiting the Exposition, the presidential motorcade, accompanied by a fleet of local dignitaries, proceeded along Magnolia Avenue and then Gay Street, from Fifth Avenue to Main, where houses and shop windows were decorated with flags and bunting the entire way.

While thousands waited outside the Auditorium, bursting at the seams as it was, front row seats were reserved for veterans of the Civil War. Candles flickered in the Auditorium’s interior archways as Knoxville Mayor Samuel Heiskell introduced the President: “You will have found nowhere a warmer welcome than that awaiting you in Knoxville.” Taft’s message extolled the virtues of peace, while declaring his own understanding that “war is hell.” Three years later, at the outset of the Great War, those words may have seemed prophetic.

A stereographic photograph showing President Taft (the mustached man in the back seat) arriving for his speech at the Auditorium Rink in 1911. (McClung Historical Collection.)

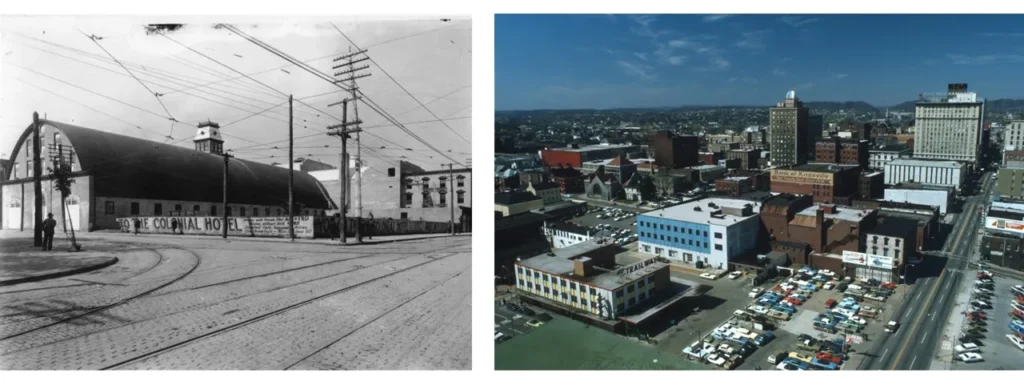

By 1916 or so, enthusiasm for the Auditorium Rink appears to have run its course and was converted into a streetcar barn. Then, after being forced out of the Union Terminal Bus Depot up on the 300 block of Gay Street following a “ruling by the State Railroad and Utilities Commission,” Smoky Mountain Trailways, part of the National Trailways Bus System, built a new bus depot here that lasted for several decades.

Two views: The Auditorium Rink, circa 1909, and the Trailways Bus Depot (lower left), circa 1970s. (McClung Historical Collection.)

Which brings us back full circle to the former Whittle Communications building. After acquiring Esquire magazine in the late 1970s, Chris Whittle built a publishing empire (originally called 13-30) here in 1991. After the company collapsed three years later, the complex was restyled into the Howard Baker Jr. Courthouse and remains so today.

The Beloved Woman of Justice bust by Audrey Flack at the Howard Baker Jr. Federal Courthouse. These photos were taken in 2018 and 2024 so it appears it’s had a recent facial. (KHP.)

While you may never need to go inside this federal courthouse, there is certainly one remarkable feature that’s worth checking out if you’ve never seen it yet—one of downtown’s most memorable statues, the “Beloved Woman of Justice” bust by Audrey Flack (1931-2024). It looks a bit like a ship’s masthead of the Greek goddess Hera as seen in the 1963 Ray Harryhausen stop-motion epic Jason and the Argonauts. But the startling sculpture actually depicts a Cherokee tradition where an honored woman is entrusted with special judicial powers and harkens back to the 18th century and earlier times when the area that later became Knoxville was a cherished hunting ground for Cherokee people. The artist and Sen. Baker attended the statue’s unveiling back in 2000, so it has graced this courthouse for a quarter century already.

Leave a reply