Chug Rigsby, crazy drunks, radio pleas, a riverside boulevard, a new football coach, and Knoxville’s Christmas of 1925

Written by Jack Neely.

A century ago it was snowing over much of the eastern part of the nation. People anticipated a White Christmas, even if they didn’t yet have a song to go with it. Hope for a White Christmas soared in Knoxville on Dec. 23 as the temperature plummeted to 18, with precipitation likely on the way. But then it warmed a bit, and it just didn’t happen. Bristol reported snow, but in Knoxville it appeared only as a frost that had thawed before the turkey was out of the oven.

Republican President Calvin Coolidge, a true conservative in all respects, set a standard for the nation with conservative holiday decor. His White House Christmas Tree of 1925 was reportedly only four feet tall. Coolidge had lots of admirers in Knoxville, and they may have followed his example.

Of course, things change. We don’t always know why. But the current White House tree is reportedly close to 20 feet tall.

In 2025, expectations for Christmas Day are sacrosanct. If we go by holiday commercials and family sitcoms, on Dec. 25, there’s only one place to be, and that’s sitting in the living room by the tree with family, opening presents.

There was certainly that option in 1925, but there were other options, too. If you were Catholic in Knoxville, you might get up long before dawn to make it to Christmas Day Mass at Immaculate Conception at 5:00 a.m. St. John’s Lutheran was a little kinder to its parishioners; they’re Christmas-Day service didn’t start until 6:00 a.m.

If you were Episcopalian, you might already have the holiday service taken care of nocturnally; both St. John’s and St. James’ offered a Christmas Eve midnight service.

It would appear there was a period of only a short interval in the wee hours of the morning when there was no holiday music emanating from one or another of downtown’s churches. If you had two or more of those denominations in your family, the night would hardly offer enough time for a nap.

When Christmas dawn arrived, if you had a kid who was a football player, especially in Inskip, you might feel obliged to attend the big neighborhood-rivalry game between the Inskip Rollers and the Bookwalter Bears at 9 a.m. Christmas Day. (The Rollers included several stars from the Central High Bobcats.)

If you got tired of that game, and didn’t have anything else pulling on you on Christmas morning, you could take the streetcar over to Caswell Park for another, bigger game at 10 a.m. Caswell was best known for minor-league pro baseball, but community football teams used it, too. The Gray-Piper Military Academy Flying Cadets, who had played the industrial Fulton Sylphon team at Shields-Watkins Field the previous week, came to Caswell on Christmas morning to challenge a group of former high-school heroes, mostly from Knoxville High and Central, called themselves the Old Stars. One key player for the Old Stars was reportedly a veteran of the Irish Navy. Of course, sportswriters of the 1920s loved inside jokes, and it’s sometimes hard to pry fact from fiction. But Gray-Piper was a drugstore on West Cumberland Ave. Its “Military Academy” is never mentioned except in the context of that football team. The Journal covered it. “The gridiron was muddy and very slippery,” they noted, referring to players by their nicknames: Pinkie Walden, Sheeny White, Granny Horne, Strawberry Hines. The Old Stars won in a tough defensive struggle, 12-7.

If that wasn’t enough live, in-person local football for you on Christmas Day, another neighborhood rivalry was over at Knoxville College’s field, where the Knoxville Negro Red Jackets were playing the Mechanicsville All-Stars at 2:00. One section was reserved for white spectators.

To attend it, of course, you’d have to miss some matinees downtown. The Bijou, in particular, was hosting “A Christmas Festival of Fun!” with several vaudeville acts, as part of a show performed three times that day, the first at 2:30. The headliner was comedian Stan Stanley, but also drawing interest was singer Ted Leslie. Ted was a young woman, actually, reported to be “chock full of talent and magnetism.” Comedian Jimmy Fox put on a humorous short farce called “The Goat.” The Wheeler Trio, a family of acrobats, kept things from getting tiresome. Then there was “A Trip to Melody Land.” Descriptions aren’t handy, but it presumably involved live music, in an era becoming famous for melodies.

The Keith Vaudeville troupe put on a total of 15 shows during their Knoxville stay, three a day on Dec. 24, 25, and 26. Then on to the next city. Competing for the Christmas-Day traffic, movies were showing at several theaters. The biggest and newest was the Riviera, which was showing Rudolph Valentino’s Cobra, billed as “a strictly modern story of tempestuous love,” co-starring the dark and voluptuous Nita Naldi. It was one of Valentino’s last movies. The original matinee idol died of appendicitis the following summer, at age 31.

At other theaters were two new silent movies starring lovely young Alice Joyce, “The Madonna of the Screen.” Her recent film, The Home Maker was at the Queen, across from the Riviera, with an interesting story about a husband and wife reversing their roles as a result of his failed attempt to commit suicide; and The Mannequin was at the Strand, before its formal release date. It was another story about marital stress, this time elicited by a nurse who kidnaps a baby. In supporting roles were Zasu Pitts as the kidnapper, and the young Walter Pidgeon.

Both those movies starring Alice Joyce were playing on Christmas Day in theaters a block from each other on Gay Street. (Joyce was later Knoxville-raised director Clarence Brown’s fourth wife; Brown became her principal supporter after her career ended, and even after their marriage ended. Of course, none of Knoxville’s moviegoers could have guessed that in 1925, when Brown was then still tarrying with his second wife.)

You could walk from one cinema to the other on the 25th, and have a Christmas dinner on the way. O’Neil’s Café at 515 Gay St. was offering “Special Christmas Dinners” from noon to 3, and from 6 to 9, for $1.

Whittle Springs Hotel was the stylish place for dancing, and it hosted a “large holiday dance” on Christmas Eve, and then a Christmas evening dance, with what was described as “Special Music.”

In 1925, there was so much special music, it seems careless of the advertiser not to specific, for history’s sake, what sort of special music it was. The house band at Whittle Springs was conducted by Charles H. Craig, a Cincinnati Conservatory alum, a violinist known as an interpreter of Massenet. He was bitterly skeptical of jazz, which he considered a fad that had already overstayed its welcome. But we don’t know who held the baton that night, and Whittle Springs was known to have featured both jazz and country music.

The women of UT announced another “Manless Dance” for Barbara Blount Hall—one of several forgotten trends of the 1920s. Some women would dress as men, and invite other women to attend with them. The next one would be on Jan. 8, just as everyone was returning from the holidays.

***

Many things were new and stirring in the Marble City in the mid-1920s. Radio was new. Blues and jazz were new, as was even country music, at least as a form available on record or broadcast. Bertha Walburn was conducting her Little Symphony at the Farragut Hotel. Automobiles were still pretty new, and residential developments that you needed a car to get to were brand new.

The Smoky Mountains national-park proposal was new. They were inspiring new art shows of painting and photography at places like the new Journal Arcade. Chop suey was new.

A much-smaller park, J.G. Sterchi’s 63-acre patch, open to the public since the 1880s but always privately owned, was offered to the city, for a price, to serve as a permanent park free to the public.

Football had been around for a while, but was catching on like never before. That fall, under Coach M.B. Banks, the Vols had gone 5-2-1, beating Georgia, tying LSU, losing to Kentucky and Vanderbilt. They weren’t really national contenders. Coach Banks, who was also basketball coach, left the Vols to coach at Central High.

Young men clearly loved playing football in 1925, but the messy game was not considered serious news, even in Knoxville, where the bleachers at Shields-Watkins Field held 3,200. On Dec. 23, 1925, the Knoxville Journal ran a six-paragraph article, “Captain Bob Neyland Is New Head Coach at Tennessee.” That news about the 33-year-old engineering instructor was the headline at the top of page 8.

At shops downtown, like Sterchi’s or Clark-Jones Music, you could buy 78 rpm disks of “Play Me Slow” by jazz bandleader Fletcher Henderson, or “John Henry” by Gid Tanner and Riley Puckett or the “All Go Hungry Hash House” by Uncle Dave Macon. Sterchi’s, eager to expand the market for its latest lines of cheaper phonographs, subsidized that Middle Tennessean’s early recording career.

Local favorite Charlie Oaks, the blind guitarist and singer known on the streets of Knoxville for a quarter century, had cut a few sides, including “The Death of Floyd Collins,” “The John T. Scopes Trial,” and “The Death of William Jennings Bryan.” Another, “We’re Floating Down the Stream of Time,” was the latest by George Reneau. Both Oaks and Reneau, who both played guitar and harmonica, had been known as street musicians before Sterchi Bros. sent them up to New York to make some records. They both enjoyed a moment of national fame, but then returned to the streets to play for more nickels.

Of course, the Scopes trial and the death of Bryan, the previous July, was still on the minds of his many admirers of the progressive Democrat turned evangelist, those who had crowded his funeral train when it came through Knoxville last summer. The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan, hastily cobbled together from his writings, with commentary from his widow, was selling briskly that Christmas.

***

After a predecessor radio station failed, the more durable WNOX had launched about the same time as the Bryan funeral train departed, with programming three nights a week, in association with the People’s Telephone and Telegraph Co. Most Knoxvillians didn’t have radios in 1925, but WNOX gave them a reason to pick one up at Sterchi’s or the Henry Moses Electric Shop on Market Square.

The radio studio was on the mezzanine of the St. James Hotel on Wall Avenue, at the north end of Market Square. Listeners were amazed to get to listen to the World Series via the local transmitter that October, an especially exciting series when the Pittsburgh Pirates beat the Washington Senators, and also the play-by-play for at least three Vol football games. But WNOX broadcast music, too. Among its first in-studio performers were Maynard Baird’s Southern Serenaders, the popular 10-piece jazz dance band; the Miles Banjo Quartet, which seems to have existed mainly on the radio; and a “quartet of Negro singers from the Oakland Church,” accompanied by piano. On Friday, Dec. 18 was the Hill String Orchestra, featuring “Old Time fiddling members” along with mandolin and guitar soloists. A few years before either Cas Walker or Roy Acuff were on the air, it sounds like one of the first country-music broadcasts in local history.

Set back that fall by a fire that damaged the transmitter, the station was obliged to reduce its signal to 50 watts.

In early December, Mayor Ben Morton, the first mayor to broadcast on the radio, used the opportunity to make an urgent plea for his favorite project, the one to make a national park of the Smoky Mountains. “We are all ready to roll up our sleeves and spend money to get factories for the city, and by the way to make our city even dirtier than it is today, with its clouds of smoke,” Morton said, over a signal probably crackling and weak. “In the park proposition, we have an opportunity to get a thing of beauty” that would also bring an economic benefit to the city. The next day, David Chapman, the leader of the park project, made a similar plea over the air, specifically about saving what he claimed was the last stand of virgin timber from the Gulf to Canada. “If they are cut, they are gone forever,” he said over WNOX. The “ancient trees antedating the discovery of our country… this collection of trees, plants, and shrubs that is the greatest collection of its kind in so small an area … this hardwood forest without equal in the rest of the world” were in imminent danger because profit-driven “lumbermen” wanted them now. The need for donations, Morton and Chapman both emphasized, was urgent.

On December 29, WNOX returned to the air with full power and a “special program of Christmas music” by local musicians.

***

Then as now, Christmas could often seem an accumulation of ironic tragedies. The night before Christmas Eve, Fayette Bishop, age 7, was trying to cross the street in Happy Holler, at Anderson and Central, when he was hit by a Ford coupe, and “fatally crushed.” The driver, whom witnesses believed to be a bootlegger, rapidly drove away. The boy died, his funeral held on Christmas afternoon. The driver was never identified.

A few minutes after noon on Christmas Day, 91-year-old Jennie Gammon, who lived on North 4th Avenue, was out in her Ford sedan with a younger friend, Mrs. Wright Culton, of Fort Sanders Manor. They were distributing wrapped gifts to friends in the Park City area, and on their way to a family holiday dinner, when at the intersection of East Fifth and Winona, a young carpenter named Albert Still slammed his speedy late-model Earl into their car, so hard a rear wheel came off and rolled down the street. Gammon died three hours later at General Hospital.

You might need to be an antique-car enthusiast to know what an Earl was. By 1925, the short-lived Michigan company was already out of business, having produced only 1,900 cars in its two-year history. Although police officers attending the wreck said Still didn’t seem drunk, they couldn’t help but notice that as they approached him, he was pouring whiskey out on the ground. Officers charged him with possessing whiskey and involuntary manslaughter.

The same Christmas Day, an old man from Powell collapsed on Vine Avenue. He died at General Hospital just after midnight, reportedly another “victim of Christmas whiskey.”

A woman arrested at a house on McKee Street for being “drunk, disorderly, and fighting” admitted to a judge she was “crazy drunk.” He forgave the $25 fine, on the condition that she go home to Florida.

At 5:00 on Christmas afternoon, a man named Tellico Burris was at the corner of Patton and Willow, in the Bottom, when he got in a fight with Ube Syphers, who stabbed him repeatedly. Police found Syphers hiding under a cot in a nearby rooming house. Burris was not expected to survive the Christmas season, but he did; we know mainly because three months later, the “police character,” as he became known, was arrested for stealing cars, and later for bootlegging.

It was a tradition to pardon convicts on Christmas. Gov. Austin Peay pardoned Knoxvillian D.D. Lowery serving a sentence of 5 to 15 on a robbery conviction. His pardon was “conditional on his staying away from whiskey.”

In researching the 1920s, you’ll find a lot more newspaper stories about drinking whiskey during Prohibition than at any other time in history.

Folks were less likely to be arrested at Cherokee Country Club, which was then barely outside of city limits. That same Christmas Eve, Eleanor Spence Sanford, who was with her publisher-industrialist husband Alfred owned the land soon to host the Sanford Arboretum, on Kingston Pike, hosted a party at Cherokee in honor of her visiting niece, Polly.

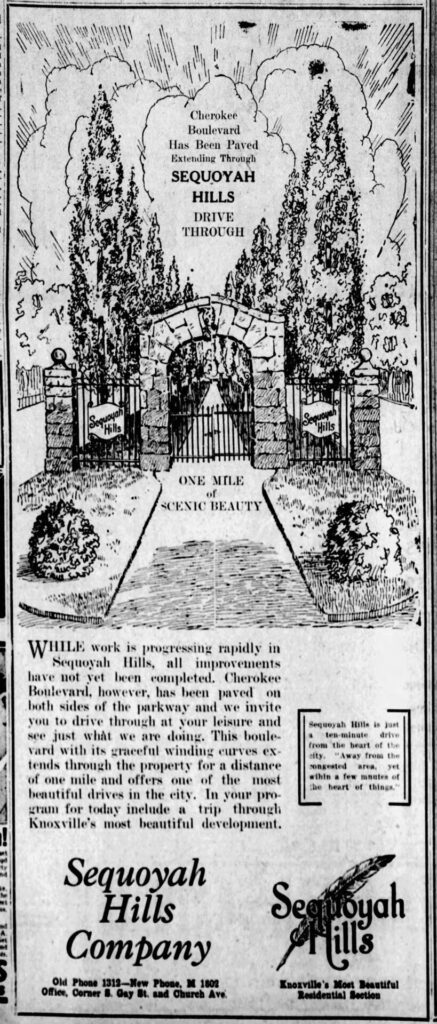

Completed that Christmas, alongside the Sanford property, was brand-new Cherokee Boulevard, hailed as a lovely drive even before there were houses on it. By Christmas, the North Carolina consortium that invested in it had already installed the stone arch hailing the entrance to the new “Sequoyah Hills,” which was promised to feature a polo grounds and an “Aviation Field” suitable for biplane landings.

At the police station was a Christmas Eve surprise party for “Mother Thompson,” the retired police matron, the first female employee of the police department. Cora Thompson, then 68, was the mother of Jim Thompson, the photographer just then becoming known for his influential photographs of the Smoky Mountains, promoting the park ideal. All her old friends were there, some of whom she hadn’t seen in years. In appreciation they gave her a Morris Chair, a classic early recliner.

“Chug Rigsby” might sound like a Damon Runyon character, but he was real, a captain in the fire department. The World War veteran was the most popular fireman at the downtown fire station, then at the corner of State and Commerce Street. As he had since about 1905, he hosted a Christmas party for the 42 children at St. John’s Orphanage, at the corner of Linden and Spruce in Park City, serving them a turkey dinner. He was a motivated philanthropist. Rigsby, whose real first name was Austin, was an orphan himself, and an alumnus of St. John’s. Portly as an adult, said to be 5 foot 8 and 240 pounds, he became the city’s unchallenged Santa Claus, soon to be hailed by thousands of children in the city’s first Christmas parades.

Rigsby had a few other claims to fame. He’d been in the news earlier in the year, at the time of William Jennings Bryan’s death. Back in 1910, on the train from Cincinnati, he shared a car with William Jennings Bryan himself. Unable to sleep, the two had sat up all night telling stories. Rigsby related that story again in 1925.

He was a favorite at the orphanage; because of Chug’s example, they said, most of the boys wanted to be firemen. He never had a family of his own, but he could get sentimental about his hometown. At the time of his death, 30 years later, a friend said “Knoxville was the only thing he had.”

His modest savings went to support the holiday dinners at the orphanage for several years. He was fondly remembered in newspaper columns by Bert Vincent and Carson Brewer for about 34 years after his death. Not much after that.

Memories fade, and the Christmas of 1925 is thoroughly forgotten. Fortunately, for that period at least, we have newspapers.

Leave a reply