The often-forgotten diversity of 1790s Knoxville

Ken Burns’ The American Revolution was a powerful prelude to the 250th anniversary of the United States. One point the documentary makes over and over concerns the surprising diversity of America’s original patriots. If they were dominated by Anglos, they also included people of French, Spanish, German, African, and Native American backgrounds.

Not that they all saw much of each other before the Revolution. During the colonial era, most colonists tended to stay within their own colonies. After the union of colonies for a common cause, and the creation of a new nation without colonies, they moved around. Where many of them moved were towns that seemed to have a future, like territorial capitals. During George Washington’s presidential administration, the capital of the Southwest Territory was Knoxville. It was still attracting newcomers later, when it was the capital of the new state of Tennessee.

Many people, sometimes even historians, assume Knoxville was formed mainly by folks from the mountains, mainly Scots-Irish, who finally got up the gumption to come down and found themselves a city. It’s not hard to come to that conclusion. The three settlers we hear most about are James White, William Blount, and John Sevier, who were from North Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia respectively, not very far away, at least not at first glance.

We’ve always heard about the staunch Scots-Irish, who have been the subject of dozens of books and countless lectures. They were the people of Scottish ancestry, many of them Presbyterians, who had lived in Northern Ireland for a few generations before migrating further to America. Characterized as independent-minded, pugnacious, and generally rootin’ tootin’—whether ethnic personality characteristics are sometimes exaggerated is not our subject today—they may well have composed the single biggest ethnic group among East Tennessee’s earliest European settlers. People talk about them as if they were the only people here. But that impression lasts only as long as it takes to start looking into the background of our founders.

The Scots-Irish were indeed an interesting group, and many of those stories are real. James White, credited as founder of Knoxville and a former captain in the North Carolina militia in the latter part of the Revolutionary War, was apparently of Scots-Irish stock. His mother was born in Ireland, and his father’s parents were both from County Donegal, in Northern Ireland where the Scots-Irish predominated.

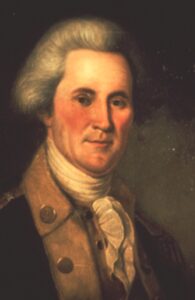

White himself grew up in what’s now Iredell County, N.C., just 200 miles east of here. Territorial Gov. William Blount, who named Knoxville and made it a city people had heard about, was from North Carolina, too, but a world away from White’s hillside home. Blount grew up in Bertie County, N.C., bordering on the saltwater Albemarle Sound, on the eastern seaboard part of the state where, even today, accents are noticeably different. He participated in the Revolution, too, if mainly on the paperwork side of it, as paymaster of the Continental Army. Which, if Burns’ documentary is accurate, must have been a frustrating job, because they rarely had any money. By the time he came to Knoxville, he had also lived in Philadelphia for a while, during which time he became a signer of the U.S. Constitution.

Said to have been of English and Norman French ancestry, Blount doesn’t sound very Scots-Irish. The fact that Blount was not a loyalist Tory may seem a little surprising. He may have borne some secret sympathy for the British, as the facts of his later career, which included a serious charge of treason, would suggest.

The other famous settler seen in the streets of Knoxville was John Sevier, regarded as one of the southern heroes of the Revolution; he commanded troops at the decisive Battle of King’s Mountain (which took place not far from James White’s childhood home). He was born and raised in Northern Virginia, about 400 miles northeast of here, and not far from Jefferson’s home. His father, Valentine Sevier, was an immigrant from England, but that doesn’t tell much of his story. The Seviers were from northern Spain, a part controlled by the French. Valentine’s father—John Sevier’s grandfather—was named Juan de Xavier. John Sevier was probably mostly English, but at least a quarter Spanish. Portraitist Charles Willson Peale gave him dark eyes and features that could pass for Mediterranean.

Some of the first Knoxvillians were from neighboring states and territories, but many weren’t. A rather large component of our first citizens were from Eastern Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, and the location of Valley Forge and the battlefields of Brandywine and Germantown. We can only guess what they witnessed of all that, but Pennsylvania names resonated all over town then, and to this day.

Charles McClung was one. Son of an Irish immigrant, he had worked in business in Philadelphia before he moved south, where he married James White’s daughter. It was Charles McClung, a teenager for most of the Revolutionary War, who laid out Knoxville’s street grid in a pattern that seems inspired by Philadelphia’s, with a little borrowing from Baltimore.

Also from Pennsylvania was Samuel Carrick, our first educator and churchman, founder of both Blount College, in 1794—it evolved by degrees into what we know as the University of Tennessee—and our first church, First Presbyterian, though he died without ever seeing his congregation build a church building.

The prominent Ramsey family were from Pennsylvania, too, probably a little farther west than the McClungs, but in the eastern half of the state, to parents who had previously lived in Delaware and Maryland. Samuel Ramsey was an educator and Presbyterian clergyman and seems to have been the guy who shamed Knoxville into finally building its first church.

His older brother Francis Ramsey was a surveyor, clerk of the state senate, an early leader in banking, and builder of Ramsey House, the durable first known use of Tennessee marble in architecture.

The guy who designed and built Ramsey’s famous house, Knoxville’s first accomplished builder and architect, was neither Scots-Irish nor Appalachian. Thomas Hope, an Englishman from Kent, learned his trade in London. During the Revolution, he was just a young man living and working in England. He crossed the ocean in the 1780s to work on some jobs in Charleston, and seemed to be a respected architect of fine homes there. But he crossed the mountains to try his luck at the new territorial capital in 1795 and spent the rest of his productive life here. Although he had designed several fine houses in Charleston, Hope’s only work that is known to have survived is here, Ramsey House and the West Knoxville private home known as Statesview.

Our first journalist was from almost a thousand miles away. Born and raised in Boston, George Roulstone may well have passed Henry Knox in the streets. Roulstone founded the Knoxville Gazette, Tennessee’s first newspaper, and his sympathies were obvious from the very first piece he published in it: Thomas Paine’s brand-new book-length essay, “The Rights of Man.” Printed in the Knoxville Gazette serially in 1791 and 1792, it was probably the longest piece of nonfiction ever published in a Knoxville newspaper, even to this day—and perhaps also the most controversial.

If Roulstone was the most radical of the early Knoxvillians, maybe he had learned radicalism firsthand. The Bostonian was 9 at the time of the Boston Massacre, 13 at the time of the Boston Tea Party, and about 14 at the time of the fighting at Lexington and Concord and the subsequent Battle of Bunker Hill, and 15 when British lifted the Siege of Boston.

He was likely within earshot of wherever he was at the time. For all we know, he may have suffered post-traumatic symptoms before he was old enough to be a soldier. But Blount recruited Roulstone to come to Knoxville, because a government needs a printer to publish the laws passed by the legislature, and a capital city needs a newspaper. Roulstone likely thought of himself as working indirectly for General Washington, a hero to many his age, and whom he might have seen in person.

Besides serving as Tennessee’s first newspaper editor, this Bostonian was the city’s first postmaster, a cofounder of our college, and the publisher of Tennessee’s first law books. He accomplished a great deal for a guy who died at 36. But he left much of it to his wife, Elizabeth Gilliam, who for the next four years was publisher of the Gazette, and the official state printer, one of very few women who held an official state post in the 19th century. (Her origins are less well known; Gilliam is an English name, but with French and German roots.)

Of Knoxville’s first five mayors, two had foreign accents, as immigrants from Ireland and Scotland. A third—our first doctor, Joseph Strong—was from coastal Connecticut. He hired Thomas Hope to design and build his “Maison de Sante”—literally House of Health—in downtown Knoxville.

James Park, who was Knoxville’s second and fourth mayor (we’re just counting him as one) was from Ireland, could be called Scots Irish. He built the brick house, commenced by John Sevier, that still stands at the corner of Cumberland and Walnut.

The other immigrant was not Scots-Irish, but just Scottish, in fact about as Scottish as it’s possible to be. Donald McIntosh was born at Inverness and studied at the famous University of Edinburgh before coming to Knoxville, for reasons of his own.

Paul Cunningham, one of the very first known pioneers to make a home in what we know as South Knoxville was from Scotland; one story has it that he was born on the ship as it crossed the Atlantic in 1735, but sources suggest he was about 5 at the time he arrived.

Another Scot was the proprietor of what was probably Knoxville’s best-known early hostelry, Chisholm’s Tavern. A lively character with an unpredictable side, John Chisholm was one of the partisans of the abortive State of Franklin, and sometimes doubled as a judge and as a diplomat, traveling to Philadelphia on a few occasions in the company of Native Americans to mediate peace between tribes; his second wife, Martha, was a mixed-race Native American. He also returned to Britain at least once, partly on a secret mission concerning his friend William Blount’s international conspiracies, tarrying in London just long enough to be arrested for vagrancy.

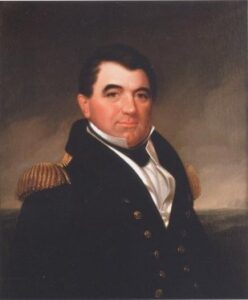

Among Knoxville’s early Revolutionary settlers, the most exotic was a Spaniard from the Mediterranean island of Minorca. He called himself Jordi Farragut-Mesquida, but we knew him as George Farragut. Raised as a seaman, before he came to Knoxville he had seen much of the world, even battled with the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, and reportedly came to America just to fight the British, which he did at Charleston Harbor. That service has earned him some posthumous acclaim as one of the most prominent Latino patriots in the Revolutionary War.

Befriended by Blount and lured to Knoxville, Farragut became a popular character among the earliest Knoxvillians, even though he never learned to speak English fluently. He might have stayed here if not for Jefferson’s initiative to recruit Spanish and French-speaking people to take charge of the new Louisiana Purchase, and govern New Orleans, which had seemed ungovernable by Anglos. He took with him his remarkably bold son, the future admiral.

It’s a challenge to try to guess what they sounded like; many of Knoxville’s first settlers had very different accents. One of those was Irish-born Thomas Humes, who built the building we know as the front of the Bijou Theatre—he apparently didn’t live to see it finished. His son later became an Episcopal priest and an important leader at the university, president when it became the University of Tennessee. And John Adair, who has an interesting distinction.

In early 1796, 55 delegates from across President Washington’s Southwest Territory gathered in downtown Knoxville to create Tennessee’s first state constitution. There were people you’d expect to find, James Robertson, Andrew Jackson, W.C.C. Claiborne, guys associated with the South. But if you review all the backgrounds of the founders of Tennessee, about a third of them were from Pennsylvania, each with his own story of how he found his way south. (Of course, though women sometimes make surprise appearances in our history, we can use the male pronoun safely in this case.)

Moreover, two of the founders of the state had Irish accents, and one of them was Knoxville’s John Adair. Unlike many immigrants who arrived as children, Adair was almost 40 at the time he came to America from County Antrim, first settling in Baltimore. Like anyone who was well into adulthood before crossing the ocean, he probably always sounded like a foreigner, but he found important roles here, including helping to provide financial backing for the soldiers who fought at King’s Mountain. Adair was on Knox County’s first governing body, a member of Blount County’s first board of trustees, and one of the first ruling elders of First Presbyterian Church.

Of course, there were other people, too, some even of different hues: Black people, enslaved and some perhaps free, who were part of the mix. We know only a few of their names, and usually just first names: Cupid, Hagar, Venus, Jack, Nann, Hector, Esther, Isaac, Mauk, Issabella. We can only hope more details of their lives come to light someday. There were also Cherokee traders who became familiar figures downtown. It’s not impossible that the Cherokee Nation’s most influential scholar, Sequoyah, a partially disabled silversmith from Tuskegee, about 30 miles to the southwest on the Little Tennessee River, might have found himself in town on occasion. There’s some dispute about his birthdate, but at the time of Knoxville’s founding, he was probably a teenager. Years later, his Cherokee alphabet would be used in the Cherokees’ first newspaper, the Phoenix—and the first known books to be published in the new written language, including a guide to Sequoyah’s work, rolled off Knoxville’s printing presses.

Evidence of enslaved handprints who helped build Blount Mansion. (Michael Jordan/Blount Mansion Association.)

There are more. Knoxville in the 1790s was a sort of imperfect rainbow coalition, or sometimes perhaps more resembling a Babel of different backgrounds, accents, and points of view. We will tell more of the story of Knoxville’s original founders, where they were from and how they connected to the Revolutionary War, as we approach the nation’s 250th birthday next year.

By Jack Neely

Leave a reply