Just beyond the edge of the town’s original 64 lots laid out in 1791, the intersection of Gay Street and Clinch Avenue has long been a bustling place in downtown Knoxville. Today, thousands of people walk or drive through here on their way to work, to see a show at the Tennessee Theatre, visit the East Tennessee History Center, grab a beer at Clancy’s, spend a night or two at Hyatt Place.

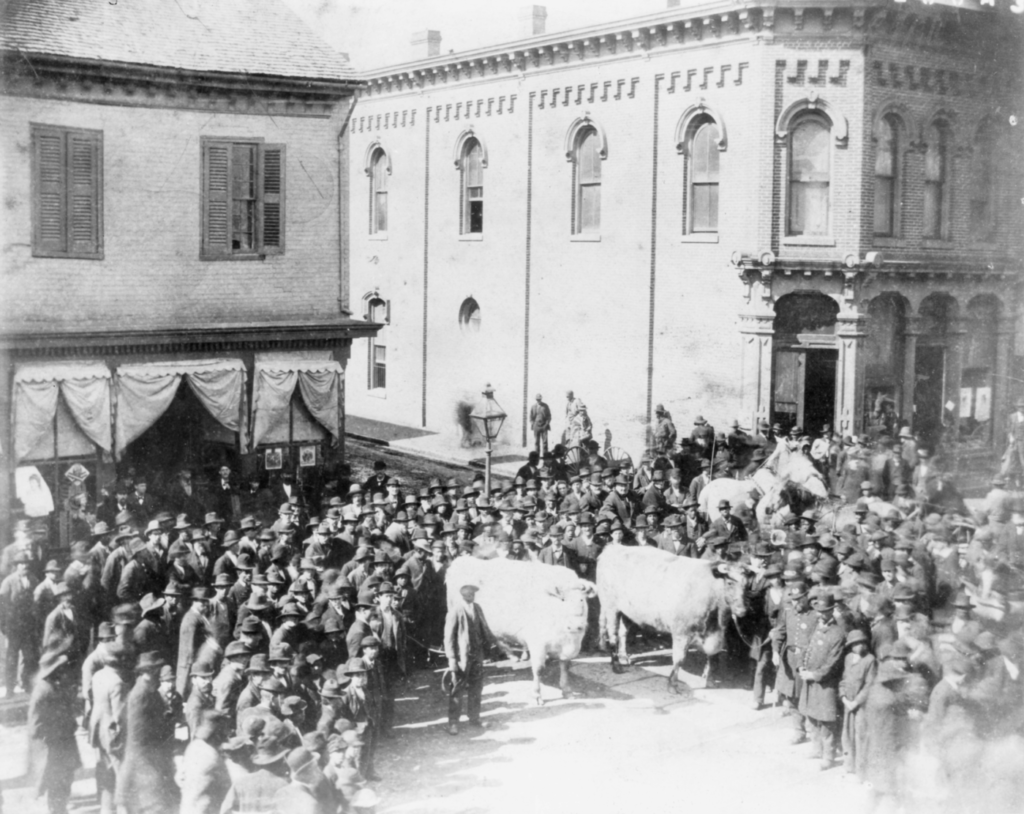

About 150 years ago, a large crowd gathered one day on the southwest corner here to pose with Col. Perez Dickinson and his “Mammoth Island Home Steers.” They would achieve photographic immortality.

Col. Perez Dickinson and his prize steers on the southwest corner of Gay Street and Clinch Avenue, circa late 1870s. (McClung Historical Collection.)

A wealthy Massachusetts-born merchant and banker, and cousin of poet Emily Dickinson, Col. Dickinson had moved to Knoxville in 1829, following his brother-in-law who served as the principal of the Knoxville Female Academy. After studying at East Tennessee College (later UT), Dickinson went into business with James Cowan (one of the town’s earliest merchant families), which led to a prosperous career in the wholesale grocery and dry goods business. Dickinson once served as president of First National Bank where, during his tenure, its stockholders were “often paid in gold.”

Raising cattle, as well as pigs, vegetables, and ornamental plants, on his 1870s “Island Home” model farm in South Knoxville, where his steers were considered a star attraction, Dickinson was more than just a notable Knoxvillian. He was genuinely loved and appreciated for his generosity to everyday people, who he invited to his farm as often as well-to-do folk.

That photograph is a classic of the bygone days of Knoxville. And the steers were indeed massive—they each weighed about 2,500 pounds. Selling them at 10 cents a pound made Col. Dickinson a fair profit, maybe about $16,000 in today’s money. After being purchased at auction, they were sent to the Palace Livery Stable on Commerce Avenue near Central and then shipped to Petersburg, Va. A few days later, a massive steak from one of the butchered steers was sent back to Knoxville and auctioned off, with the proceeds going to charity.

The closest auction site would have been just few yards from here, behind the main building on the left in the photograph.

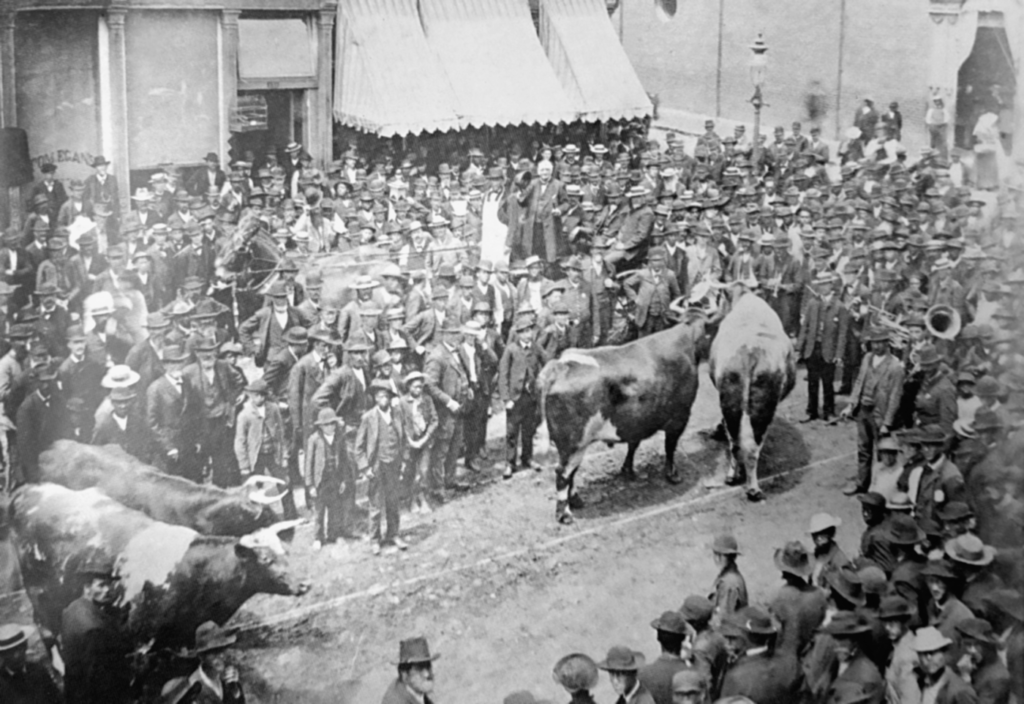

But there’s another, similar photo that I noticed a few years ago in an old book by Betsey Beeler Creekmore. I recently tracked down an original copy of the picture at the McClung Historical Collection. It’s from a slightly later date and shows Dickinson showing off more of his fine cattle, and shows almost everyone’s faces in greater detail, young and old, and every hat and crazy beard. Amongst the crowd are members of a brass band (news items suggest that it was Tom Humes Brass Band), and to the far right, walking by the entrance to what I believe is a drugstore, are at least two women, giving a slight balance to all the testosterone on view. You can tell this photo was taken a few years later as the building on the left has had a slight makeover and you can even see a newer gas lamp on the street. It may be one of the very best photographs of Knoxvillians from the really old days, and the details of the building on the left offer more clues about this intersection.

Col. Perez Dickinson stands on a carriage outside Tom Egan’s saloon at Gay and Clinch, circa 1878. (Betsey Beeler Creekmore Collection, McClung Historical Collection.)

The Fouche Block (to the left) was built in 1875 by John Fouche (1817-1898), recognized as the city’s earliest dentist, and a respected one. According to news columnist Carson Brewer, Fouche first rented rooms here for his dental practice on this corner in 1847 while his family lived above. By 1865, he had purchased the building, and a decade later purchased the lot and replaced it. By 1878, he let his rooms to another dentist, J.T. Cazier from Jonesborough, Tenn. His name is just visible on the window ledge in the photo.

Below Cazier’s practice was Irishman Tom Egan’s bar room—just the sort of place to take a swig of brandy after having a tooth pulled by those old and scary looking tooth extractors one might see at the Museum of Appalachia. If it is indeed the same man, Tom Egan later ran the bar at the Hattie House Hotel across the street.

The Federal Custom House, behind the Fouche Block, was designed by U.S. Treasury Department architect Alfred Mullet and completed in 1874. Clad in local Tennessee marble, the building still stands on the corner of Clinch and Market Street as a monument to Knoxville’s burgeoning marble industry of the period. Post Office operations occupied the entire first floor.

The courtyard between the Custom House and Post Office (left) and the rear of the Fouche Block (right), circa 1880s or 1890s. (McClung Historical Collection.)

The courtyard between the two buildings would have created a nice open space to service postal deliveries, and also stage auctions like in the following image where an assortment of cabinets, beds, and chairs are all laid out.

The courtyard proved to be a fertile ground for peddlers, hucksters and mountebanks, and at least one, well-liked auctioneer, as a 1922 news story on the Custom House attested:

“Do you remember when the eastern half of the federal building was an empty lot, and medicines and drugs, that it was claimed would cure every known ill known to humanity, were vended from it by sleight of hand, of hand artists, and orators mounted on soap boxes? Also, when “Uncle Ned” Akers was heard there every Saturday morning in the role of auctioneer of house-hold goods?”

Col. Akers arrived in Knoxville about 1870 from Virginia where, in his “stentorian tones,” he had already enjoyed a long career, auctioning off practically everything that one could think of, including, before emancipation, slaves. Here, he was described as a “good-natured, jolly, popular, inimitable, irrepressible, and indefatigable, auctioneer.”

There is currently an enlargement of this photograph on the exterior of the East Tennessee History Center, right at this very spot. Along the north side of Clinch Avenue one can see a mismatched row of buildings, and next to the “FISH” sign, the office of “J.W. Gaut.” Born near Dandridge, Col. James W. Gaut (1823-1904) developed a successful wholesale grocery business, and held several prominent positions, including president of the Knoxville Board of Trade in the early 1870s. Having an office here, assuming he kept it for 20 years, would have been especially convenient when he landed the job as Knoxville postmaster in the 1890s.

The Frances Willard Women’s Christian Temperance Union public drinking fountain, looking south from Clinch Avenue toward the old Deaderick Building (that fronted Market Street) on the far right, circa 1900. (KHP.)

In 1898, this courtyard received a major makeover, and a small park was laid out. Not long afterward, a public drinking fountain was erected and paid for by the Frances Willard Women’s Christian Temperance Union, in memory of the nationally renowned educator, temperance leader and suffragist. About 10 years after that, the park was reduced in size when an addition was built on the eastern side of the Custom House.

Although the new addition mirrored the look of the western side on Market, today we can no longer see the original east-facing Custom House façade. Or can we?

In fact, yes, we can. Head into the East Tennessee History Center, take the elevator up to the third floor, and walk through the McClung Historical Collection. Before you get to the reading room (where the Federal court convened) you can look through a window and still see most of the eastern façade, at least the top two floors of it. When the 1909 addition was designed, the architects created a “light court,” to naturally illuminate the Federal Courtroom.

A view of the “light court” and the original east-facing façade of the Custom House at the McClung Historical Collection. (KHP.)

After it was built, the Fouche Block stood on the corner of Gay and Clinch for more than a quarter of a century before it began to be dwarfed by tall buildings on all the other corners of Gay and Clinch. In relatively short succession, beginning in 1907, the Knoxville Banking and Trust Building (later named the Burwell), went up, followed five years later by the marble-clad Holston Bank Building, and in 1920, the Farragut Hotel was completed (much taller than its predecessor, the Imperial Hotel).

Still, the Fouche Block endured. One notable business lasted 40 years, yet most people probably didn’t even realize that was even there: Comer’s Sport Center. Located on the second floor, perhaps part of the old dentistry rooms, above later mainstays like the Brass Rail restaurant (run by Greek immigrant Frank Kotsianas), the colorful pool hall, run by Dick Comer, was immortalized by Cormac McCarthy in his classic Suttree (1979) and also one of his last titles, The Passenger (2022). At one time, Comer’s was known for its legendary burgers and beef stew, and also prided itself on being a “serious pool hall” that didn’t sell beer. But during its early days it was raided multiple times by police attempting to root out illegal gambling.

In Suttree, set in the 1950s, McCarthy described how the title character, Cornelious Suttree, “went up the alley and up the back stairs at Comer’s,” where Dick Comer winked at him on arrival, and where Suttree liked to sit and look down on street life at this intersection across from the Tennessee Theatre.

“He’d sit on the front bench at Comer’s and watch through the window the commerce in the street below, the couples moving toward the box office of the theatre in the rainy evening, the lights of the marquee slurred and burning in the wet street.”

Another time, after a rare shopping spree with a new lady friend, Suttree “…appeared at Comer’s in a pair of alligator shoes and wearing a camelhair overcoat.”

The 600 block of Street with the Fouche Block on the far right, near the Holston Building. The red sign on the lamppost advertises Comer’s. (Knox County Archives/McClung Historical Collection.)

An early 1970s aerial view, looking east towards the rear of the Fouche Block (top left), gives a sense of the depth of the building, and its location in relation to the Custom House. (Knox County Archives.)

When the Fouche Block, and its connected buildings, were demolished in 1993 for a city development project that went unrealized, the vacant lot sat idle for a decade (the East Tennessee History Center addition to the Custom House was completed in 2003). Someone planted some grass seed that grew to spell the word “P A R K,” which not only described their hopes, but also, perhaps unknowingly, referred to the old days when there was indeed a park back there behind the building in the Custom House courtyard. But no steers, or cattle of any kind, staggered along Gay Street to munch on the grass.

Thanks to Betsey Creekmore, Brent Minchey, Wes Morgan, and Joanna Bouldin at McClung Historical Collection, for their help with this story.

“Ghost Walking” is my own take on life on the city’s streets in bygone times; how these streets and their buildings have changed through the years, and how through old pictures and stories we can glimpse the echoes of people’s past lives and particular events. Some of the photos featured in this series are included in Downtown Knoxville that I co-authored with Jack Neely, and part of the popular “Images of America” range. If you’re looking for spooky ghost stories, please allow me to direct you to historian Laura Still’s book, A Haunted History of Knoxville, and her “Shadow Side” walking tours. Laura has been leading historic walking tours for years and she also generously donates a portion from most of her tours to the Knoxville History Project. Learn more at Knoxville Walking Tours. ~P.J.

Leave a reply