Another historic downtown building whose future is in question

We recently ran a piece about the 1875 Peabody School / Labor Temple building, threatened by the fact that it appears to be erased in a landowner’s proposal for the property, which by one architect’s vision looks like a place for high-rise residences.

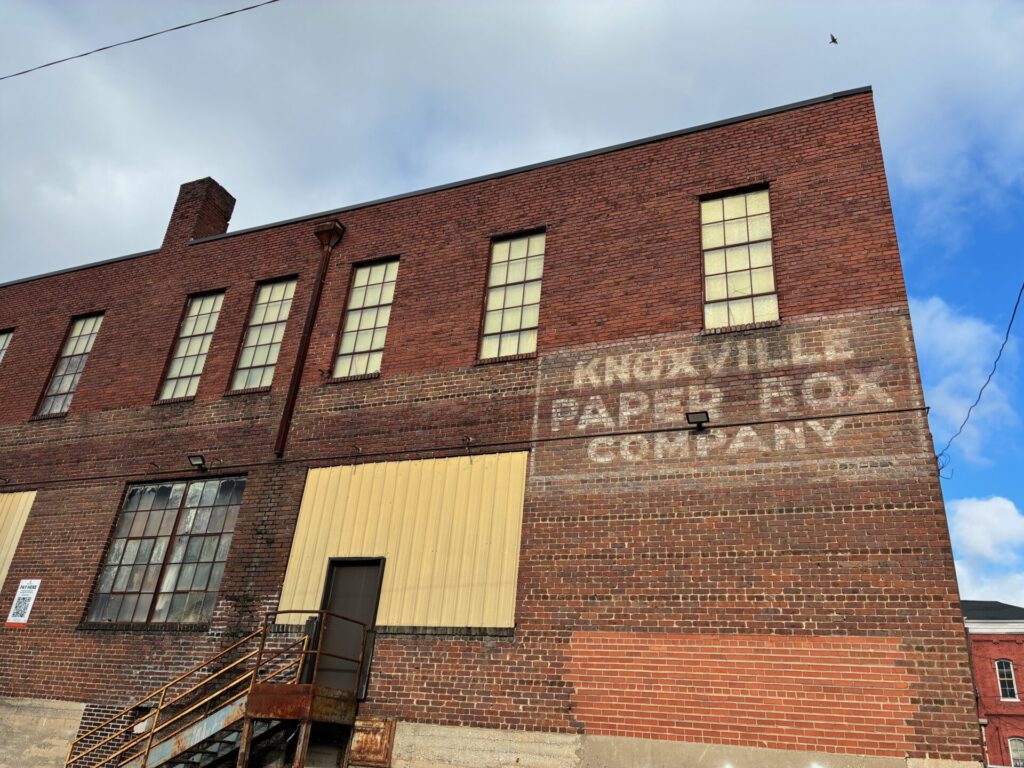

Also in the line of fire is another historic building, next door on the same piece of property. Also at least speculatively proposed for demolition with that same ideal, it’s a handsome two-story brick building more than a century old. Just east of the old mid-century Greyhound Bus station, whose future has been the subject of interesting speculation, it’s a little off the grid of what has traditionally been considered the Central Business District, or the Old City. The big brick building holds more than 40,000 square feet of floor space, but to my knowledge has never been written about. It’s the Knoxville Paper Box Building.

The former Knoxville Paper Box Co. building on E. Magnolia Avenue at Morgan Street, November 2025. (KHP.)

The name might sound mundane and not necessarily evocative of great architecture, but this paper-box building is built of solid brick and stone. The paper-box business was essential to the success of several other industries, who shipped their products in paper boxes, and as if to remind people of that fact, Knoxville Paper Box Co. built a landmark. Described in the newspaper as one of Knoxville’s three biggest construction projects of 1921, it was stylish for the early ‘20s, when we still considered it important to fill Knoxville with buildings that looked substantial and permanent.

It was finished in early 1922, when the old Knoxville Sentinel announced, “Knoxville Paper Box Co. expects to be in its handsome new home on Park Avenue between Central and Morgan Streets by March 1. The building is one of the most attractive plants recently erected, and has every modern convenience for a factory.”

That reference to its location on “Park Avenue” may be puzzle us today, but that name “Park Avenue” dates to well before the Civil War. Likely named for the Irish Park family, who supplied Knoxville with its second-ever mayor, James Park the Elder, who was also our fourth mayor; and his son, the Presbyterian leader and author James Park the Younger. Both were associated with one of the city’s most durable early homes, the Park House still standing at Cumberland and Walnut.

Near what was in the 1850s Knoxville’s northern border, Park Avenue was the first street north of the brand-new new East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad tracks that led to the dynamic cities of the East Coast. Just after World War I, to simplify things, Park Avenue was rechristened as the western end of Magnolia Avenue, a newer but much longer street, to the east.

Historians knew about the Park family, but by 1920 they were no longer prominent. In that rapidly changing era of quick decisions, of massive annexations and major road projects, the city fathers, some of whom probably didn’t even remember anyone named Park, decided they could do without a Park Avenue. It’s likely they just deemed the name change a little gesture to make it easier for people downtown to find Magnolia Avenue, the lovely treelined residential corridor leading to the city’s most famous park.

It doesn’t serve that purpose anymore. For the almost 20 years since SmartFix, this older “Park Avenue” part of Magnolia is no longer connected to the rest of Magnolia, and it’s pretty certain that that fact frustrates somebody every day. To reach long Magnolia Avenue, you have to drive down Hall of Fame from short Magnolia. It might make sense to revive the old Park Avenue name, just to end the confusion. That may be a subject for another day. Just now we’re talking about a building.

Behind its handsome design was the architectural firm of R.F. Graf & Co. The son of a Swiss immigrant, Richard Graf (1863-1940) was one of Jazz Age Knoxville’s busiest architects. He was already notable for the landmark St. John’s Lutheran Church, on Broadway, and the rebuilt Mechanics Bank building on Gay—the 612 building that the Tennessee Theatre has acquired to expand its rehearsal and reception options as a performing-arts center. In the near future, Graf would design the newspaper office and Tennessee-marble showcase known as the Journal Arcade and the tall Sterchi Brothers building, when Sterchi was claiming to be the largest furniture company in America. The building at 200 E. Magnolia isn’t in some lists of Graf’s work, perhaps because students of architecture don’t know about it.

The Knoxville Paper Box Co. had some precedents, but was founded by name in 1913, and grew rapidly. Paper boxes were then much in demand, and are one of the few constants in business, maybe even more in demand in this day of Amazon.

At Christmas time, KPB advertised “Christmas Holiday Boxes” and “special designs in candy boxes” as well as hat boxes and other kinds of clothing containers, including glove boxes, tie boxes, shirt boxes.

Its young president, not yet 40 when he was planning this building, was Alex Hickman (ca. 1885-1960). Son of a Sevierville medical doctor, the business-college grad went into business with his brother, James H. Hickman (1883-1971), making and marketing paper boxes. James was a Baptist, Alex a Presbyterian. James seems to have been the jollier and more outgoing of the two, a leader in several social and charitable organizations.

At the time of his retirement, James Hickman, described as “a top-flight walker and talker… swinging a sturdy cane,” was known to lunch daily at the S&W on Gay Street, about half a mile from headquarters. (Just before he retired, the older Hickman was one of the first residents of the modern Hamilton House complex in Sequoyah Hills.)

Knoxville Paper Box Co. opened their new building in 1922.

It was a different city. When this building was completed, Knoxville had never had a radio station, but the predecessor of WNOX went on the air later that year. The city did have three daily newspapers, two of which, the News and the Sentinel, would later merge. No national park, the Smoky Mountains were privately owned; it was hard to get a good look at them without trespassing. Two downtown train stations were open around the clock, sending and receiving passengers to and from every corner of the nation.

Despite some efforts, by the way, in 1922 no preservation movement in Knoxville had ever succeeded. UT had just recently torn down its only antebellum buildings. The last remnants of the old Union Fort Sanders were discernible about that time and not afterward.

This immediate neighborhood of 200 E. Magnolia, still served by electric streetcars, was changing. A couple of blocks to the east, Friendly Town, the old semi-legal red-light district, had closed in 1915. To the west a few elderly neighbors with Irish accents who could recall the days of Irish Town, but by 1920 the immigrant community left few traces other than Jim Long’s old saloon somehow still open during prohibition, still with its painting of Custer’s Last Stand behind the bar. Peabody Elementary was still open just behind the paper-box building, while the much-newer Knoxville High School had introduced teenagers to the neighborhood. The townhouses of Fifth Avenue were still posh. Every Sunday, hundreds of Presbyterian, Lutheran, and Disciples of Christ parishioners walked to church.

To succeed, the Knoxville Paper Box Co. really just had to make good boxes. That market seems to have been pretty stable throughout the last century and more. But soon after they built this building, the KPB Co. began using a motto in their advertising: “We believe in Knoxville.”

The Knoxville Paper Box Co. name still lives on! (KHP.)

Knoxville Paper Box Co. occupied the building for about 45 years, leaving the building around 1967, not long after the death of one Hickman brother and the retirement of the other. Its assessed value plummeted about 30 percent. The retail chain Almart (pre Walmart) used part of it temporarily while they built a big store north of downtown. The rail-salvage folks began leasing parts of it around 1969. Eventually they shifted the building’s main entrance from the street façade to the parking lot in the back. To their credit, this company that scavenges merchandise from stressed sellers, including the owners of derailed freight cars loaded with furniture and architectural supplies, began thriving here when many other businesses were giving up on downtown. Operating here by several names—mostly Knox Rail Salvage since the 1980s—they’ve got their own history here, too.

In discussing our ideals of downtown’s redevelopment over the last 30 years, we’ve mostly ignored this building and its neighborhood in northeastern downtown. But with downtown’s mostly preservation-minded revival bursting at its seams, and the popular new baseball and soccer stadium, there’s been a lot of fresh construction nearby. People like 1920s- style brick buildings, whether they actually date to the 1920s or are just built to look like them.

Remarkably, some new residential and commercial buildings in Knoxville resemble the Knoxville Paper Box Co. building of 1921, as if they’re cheaper versions of an ideal. This one’s real.

By Jack Neely

Leave a reply