Just like we do today, Knoxvillians have long come downtown looking for some entertainment. For many years, Staub’s Opera House (later known as Staub’s Theatre and the Lyric) served as the city’s most dependable live-performance venue. But in the early years of the 20th century, some came to seek and try out a relatively new spectacle: moving pictures.

Several small cinemas came and went quickly in those early days, but one of the most enduring proved to be the Queen Theatre. It opened in 1914 just two doors away from the durable East Tennessee Savings Bank on the corner of Gay Street and Union Avenue.

When it opened in the heat of the summer on July 6 that year, the Queen’s owners proclaimed it to be “one of the most modern and fanciest movie theaters in town.” They also boasted “one cubic foot of fresh air, conditioned for every one of its 800 seated customers every two minutes.” On a hot, stuffy summer day that welcome comfort was likely worth the price of admission.

Looking to rise above some of its downtown competition, the Queen also promised high-quality film shows, but that’s hard to judge when looking back more than a century as many of the names of films shown during the theater’s early years appear obscure (The Man From Home, Sign of the Cross, both 1915 for example)¸ though we can relate to Cinderella (1915) starring Mary Pickford in any era. That same year, another Pickford film, Esmerelda, showed here, based on a story by Knoxville’s own Frances Hodgson Burnett, who lived here as a young girl in the 1870s. It’s possible that in 1915, a few locals actually knew Frances back then or remembered seeing the young author on Gay Street 30 years or so earlier.

One might also recognize Brewsters Millions, based on the 1902 comedy novel by George Barr McCutcheon in which one lucky young man has to spend $30 million in 300 days to inherit $300 million. Sound familiar? It was the first of many film adaptations, including a high-profile version starring Richard Pryor and John Candy in 1985.

There were other local connections. In the years before he became known as the city’s most prolific commercial photographer, and arguably the greatest photographer of the Smokies, a young-ish Jim Thompson began showing his own moving pictures here. In 1917 he brought his film to the projection booth to show footage of the “Pilgrims of Patriotism.” With a curious MAGA-like slogan from the future, “Our Country First—Then Knoxville,” the pilgrims were essentially a short-lived group of like-minded city boosters embracing President Woodrow Wilson’s call for national preparedness ahead of what would be the country’s involvement in World War I. The film showed Knoxville’s boosters (aka “Trade Trippers”) wearing their trademark grey hats with a green “Knoxville” band and red-white-and-blue umbrellas, on a southern tour of 42 towns over four days. The contingent included Col. David Chapman and Judge H.B. Lindsay (who six years later would help found the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association that would lead efforts to establish a new national park) and Lt. Gen. Lawrence Tyson, who later became a senator.

A close-up of the lobby of the Queen Theatre in 1918. Note the portrait of the mustached Lt. Gen. Lawrence Tyson in the display on the right. Click here to zoom in on these incredible vintage photographs courtesy of the McClung Historical Collection.

If the Queen wasn’t showing a film you wished to see, you could head up the street (perhaps resisting the urge to pop into popular Miller’s Department store on the way) to the corner of Wall Avenue, where the Gay Theater welcomed its first movie-goers the year after the Queen opened. The Gay initially stood apart for its use of Kinemacolor, an early type of color film using red and green filters. How much patrons cared about the novelty it’s difficult to speculate.

The Gay Theatre also touted its air conditioning, claiming to be the “coolest place in the city.” If you wanted to chill out watching a short film (most films were pretty short back in those days) like the bizarrely titled, School Ma’am of the Snake (1911), this was the place to be.

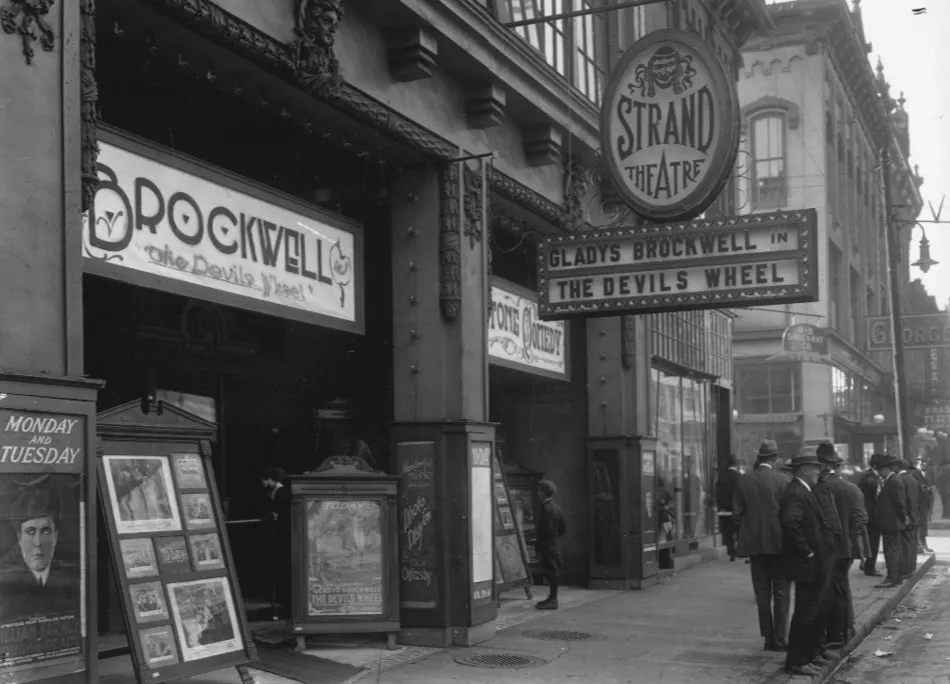

Enjoying some success, or the promise of some at least, the Gay added 500 more seats in early 1917 then closed its doors. Within six months it re-opened as The Strand, a venture that proved to be way more durable than the Gay, lasting until 1949.

The Strand Theatre on the 300 block on the east side of Gay Street, 1918. Photo courtesy of Thompson Photograph Collection, McClung Historical Collection.

If you didn’t fancy something like Thompson’s “pilgrim” film, nor what the Gay was offering, then you could just keep going up the street. On the north side of Wall Avenue, one could drop in to the Majestic Theatre, which ran for 12 years from 1910 and was the Lyceum briefly before that. But the place may have been majestic in name only. According to historian Jack Neely, the theater in no way lived up to the grandeur of its name, originally being “hardly bigger than a shoebox.”

Yet, this small unimpressive theater has achieved a small slice of immortality over the years, courtesy of Knoxville’s own literary son, James Agee. In his autobiographical novel, A Death in the Family (published in 1958 after his death), Agee described himself as a young boy, Rufus, watching a Charlie Chaplin flick there with his father. Agee wrote:

“They walked downtown in the light of mother-of-pearl, to the Majestic, and found their way to seats by the light of the screen, in the exhilarating smell of stale tobacco, rank sweat, perfume, and dirty drawers, while the piano played fast music and galloping horses raised a grandiose flag of dust.” Shortly after, Agee goes on to say…”then the player-piano changed its tune, and the ads came in motionless color.”

In those segregated times, if you were a Black Knoxvillian you had few options to catch a movie on Gay Street. The Bijou had segregated seating up on the second balcony when it opened in 1909 (and Staub’s too had separate seating for some shows), which couldn’t be said for other whites-only cinemas. For a cinema-only experience, you had to head north a couple of blocks where, clustered around Vine and Central (and up Central as well), there were several theatres for African American audiences, most only lasting a couple of years apiece, including the likes of the Dixie, Arcade, Iola, and the Lincoln.

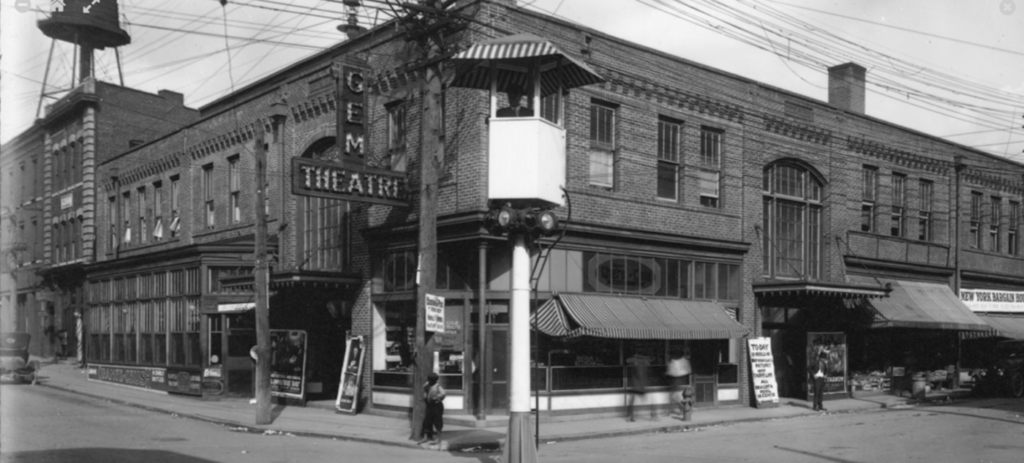

The Lincoln (on Central near Vine) belonged to the well-respected former slave, industrialist, jockey, horse trainer, racetrack owner, and saloon keeper, Cal Johnson (whose name graces his own former clothes factory building that still stands on State Street), and ran for about four years, beginning around 1907. Only the Gem Theatre endured from 1913 to 1964 (in two locations).

The original Gem Theatre for African Americans, circa 1921, when it was at 102 W. Vine Avenue. Following a fire, it moved down to 106 E. Vine. Photo courtesy of the McClung Historical Collection.

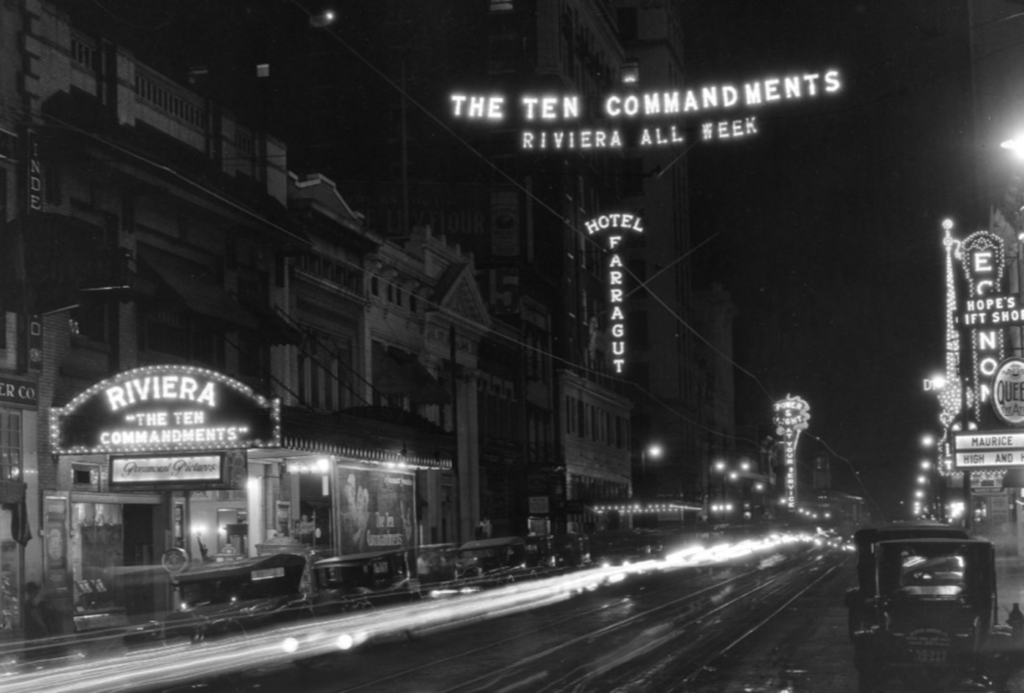

Tracing our steps back down Gay Street to Union, only six years after the Queen opened, it was surpassed by the opening of the impressive Riviera with close to 1,200 seats. When it opened its doors to the public, and not without a little hyperbole, it claimed “Those who are not familiar with its design and structure are unable to realize its stupendous magnitude and elegance, or appreciate, perhaps, what the theater will mean in the future progress of the city.”

Yet elegant it certainly was, with mahogany panels and also “Ross pink” Tennessee marble gracing the lobby, from the Ross-Republic Marble Company’s South Knoxville quarries and “dark pink” from Union County. Local Sterchi Brothers Furniture even supplied 500 yards of velvet carpet. That description paints quite a Knoxville-centric picture.

By the way, the Queen Theater lasted only eight years after the Riviera opened, closing when the far grander and longstanding Tennessee Theatre opened in 1928.

Gay Street, circa 1925, with the Queen on one side of the street and the Riviera on the other. Back then, for only a few cents, you could spend all day in the cinemas of downtown. Photo courtesy of McClung Historical Collection.

The Riviera lasted several decades until it was damaged by fire in 1963. Seven months later it was reborn as the New Riviera, running its film projectors until January 7, 1976, when rather fittingly (for this story at least), its last screening was the western, Adios Amigos. Who starred in the film? Richard Pryor, who you may recall appeared in Brewsters Millions (1985). After years of proposed restoration, the Riviera was torn down with little public notice in the 1980s.

It’s agreeable when the old names are kept alive. Thirty years later, a new publicly and privately funded cineplex opened on Gay Street right on the same spot as the Riviera once had. The Regal Riveria opened in the heat of the summer on August 31, 2007, and I hope is still going strong, or as strong as a modern-day cinema can be.

Regal Riviera at 510 S. Gay Street. Photo courtesy of Mike O’Neill for the Knoxville History Project.

PS. If you would like to learn more about the city’s cinema history, head on over to the Tennessee box office. Jack Neely’s The Tennessee Theatre: A Grand Entertainment Palace, is a book so sumptuous in its design it’s like stepping into the Tennessee itself. Plus, the lobby of the Regal Riviera features old photos of theatres as well.

Special thanks to Jack Neely for insights on early Knoxville theaters.

“Ghost Walking” is my own take on life on the city’s streets in bygone times; how these streets and their buildings have changed through the years, and how through old pictures and stories we can glimpse the echoes of people’s past lives and particular events. If you’re looking for spooky ghost stories, please allow me to direct you to historian Laura Still’s book, A Haunted History of Knoxville, and her “Shadow Side” walking tours. Laura has been leading historic walking tours for years and she also generously donates a portion from most of her tours to the Knoxville History Project. Learn more here. ~ P.J.

Leave a reply