National Cemetery Part II

PERMANENT DIGNITY AND TRANQUILITY

Attempts to beautify the cemetery came early. “A gang of twenty-five men will be employed hereafter to plant shrubbery and otherwise ornament [sic] over the graves,” it was reported two years after the war. “A fence will be erected separating the cemetery from Gray Cemetery and the walks paved.”

In May, 1867–one year before the first national Decoration Day–controversial Governor “Parson” W.G. Brownlow’s paper, the Knoxville Whig, remarked on the state of the cemetery: “About 2600 of the nation’s defenders now sleep in the National Cemetery at this place. The graves are being handsomely decorated with turfs of blue grass and by no means are spared by the nation to show the high appreciation of the services of these men. A picket fence is soon to be placed around the grounds and other improvements to be made.”

There follows a bit of polite criticism of some perhaps recklessly arranged burials, followed with a characteristic swipe at the Confederacy:

“The graves have not been as regularly laid off as they might have been, but with proper care they may be made to have a very handsome appearance. The memory of those who have fell in the great cause of freedom and liberty should be held sacred by every local American citizen to the latest generation. These National Cemeteries are a sad comment on the wicked men of the rebellion.”

The following November, an item headed “The National Cemetery” reports that “Major Wainwright, Quartermaster, U.S.A., has made extensive additions to the National Cemetery at this place. Grounds have been laid out for 600 more graves for bodies to be taken from Cumberland Gap.”

Originally from New Hampshire, William Alonzo Wainwright (1832-1904) was U.S. assistant quartermaster in Knoxville after 1865, apparently succeeding Capt. Chamberlain, who left the army at war’s end, married a local girl, and went into business. Like Chamberlain, Wainwright was principally in charge of the new National Cemetery.

A shadow fell over his career due to a complicated tragedy in early 1866, only two months after he arrived in Knoxville. At a federal warehouse on the north side of town, probably not far from the cemetery, Wainwright was in charge of a military surplus sale. He had posted a private with the U.S. Colored Troops at the back of the warehouse. A war enlistee described as a “farmer” from Middle Tennessee, the black private was about 19. Legal documents written that month have his name as Alvin Brodda. However, the army eventually listed him as Alvin Brody. He was given orders not to let anyone in the warehouse without special permission.

A former Union officer, Lt. Col. Calvin Dyer, made a purchase at the sale, and went around back to pick it up. Dyer had some sort of a conflict with Brody, and the black private shot and killed the white officer.

It was a matter of local outrage, especially considering that the dead officer had served during the war with James Brownlow, brother of the editor of Knoxville’s main newspaper, and son of the Unionist governor. Friends of the deceased criticized Wainwright for his lax treatment of a murder suspect. Wainwright placed the alleged killer under the custody of other black soldiers. In short order, Brody escaped.

Although Brownlow’s Whig was a pro-civil-rights paper, especially by the standards of the time and place, the paper accused the black soldier of vicious and intentional murder, and fanned the racist flames among a postwar populace already uneasy about the presence of armed blacks in military uniforms.

Rooted out of hiding in a slum section on the north side of town, Brody was lynched by an angry mob composed mostly of Union veterans who may have felt they were avenging their comrade’s death. The mob chose to hang the accused right in front of the Gay Street home of the new quartermaster, W.A. Wainwright.

Unusual as it was, it’s the only certain example of a racially motivated lynching in Knoxville history. Although there were other postwar lynchings–a former Confederate soldier accused of murder had been lynched downtown five months earlier–a note left with Brody’s body included a racial slur. Combined with multiple other episodes of violence involving soldiers or former soldiers of both races, in the unsettled postwar era, it was quickly forgotten. Alvin Brody, as the inscription on his grave has it—was buried at the National Cemetery.

In some parts of the South, blacks and whites were segregated even after death. This rule does not seem to have been followed quite as strictly in Knoxville in general, though most graveyards are overwhelmingly occupied by members of one race or the other. (A few blacks, some of them servants, are buried at Old Gray, within white family plots.) It seems never to have been an issue at National Cemetery. In the first two years of the National Cemetery, many of the soldiers who lived and died in the Knoxville area were members of the U.S. Colored Troops. The abbreviation “CLD” appears on dozens of gravestones. Soon after the Civil War, Knoxville National Cemetery may have been the region’s most racially integrated cemetery.

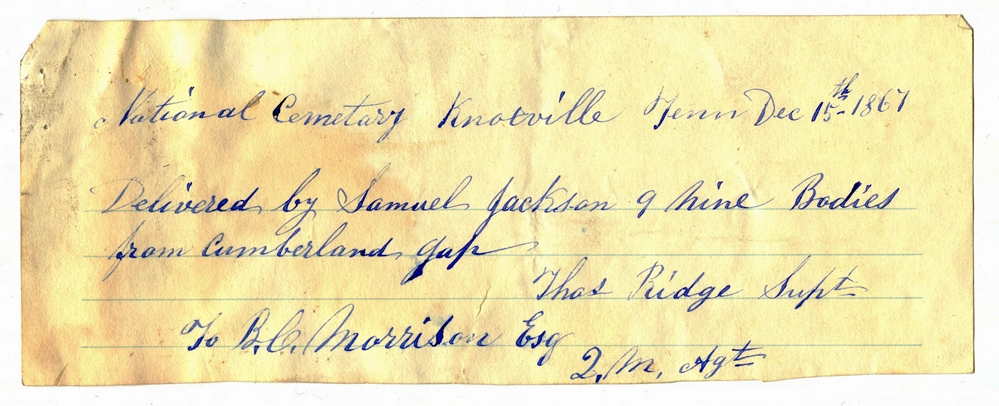

Receipt for soldiers bodies moved to National Cemetery for reinterrment. The note reads, “Delivered by Samuel Jackson 9 nine bodies from Cumberland Gap. Thos. Ridge Supt.” Tennessee State Library & Archives.

In late 1867, National Cemetery received scores of Union bodies from Cumberland Gap, which had been a battlefield off and on throughout the war. The government paid a bounty for each body delivered to the National Cemetery. Hauling corpses that were a few months or years old, for miles over dirt roads, was a job that likely appealed only to the desperate, or the very ambitious.

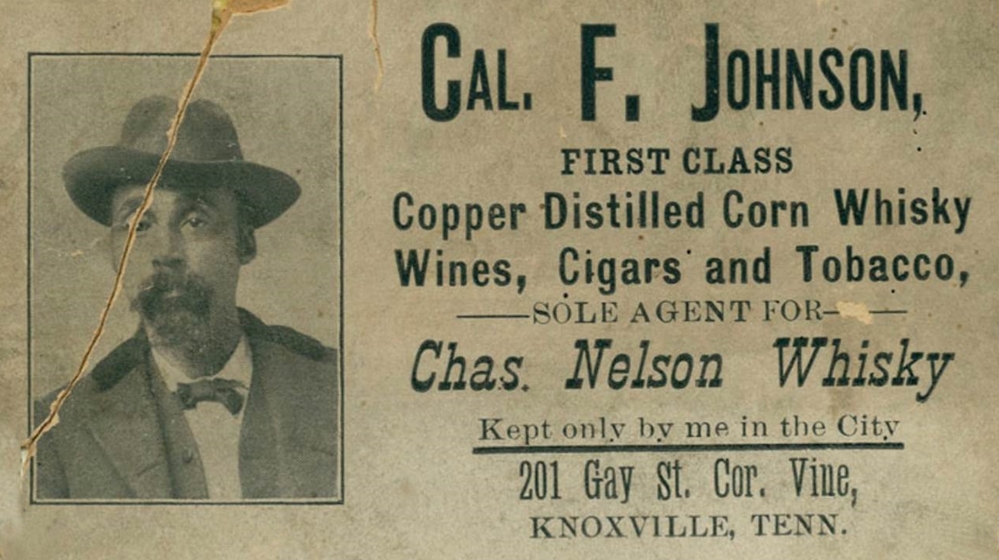

That’s likely the time that the industrious young former slave, Cal Johnson, about 21 at the time, participated in the program, according to a story published repeatedly since 1887, earning the capital to begin a significant business career. Within twenty years of his emancipation, Johnson was a leading businessman in Knoxville. Despite the obvious problems of a black man in the South during the days of

Jim Crow — moreover one with no formal education — Johnson became the owner of a chain of saloons serving both the black and white parts of town, became involved in horse racing and real estate, and even became a philanthropist, donating funds to improve the city park that bore his name.

Thus the Knoxville National Cemetery apparently played a role in launching one of the most remarkable business careers in American history.

***

A report of the quartermaster to the Secretary of War in 1868 described Knoxville’s National Cemetery. “it is beautifully laid out in concentric circles, with walks and avenues (which have been macadamized with broken rock) radiating from the centre, where a flagstaff has been erected, from which floats a beautiful national flag, presented by the ladies of Knoxville.

“It is enclosed by a substantial panel fence. The graves are well sodded and are provided with numbered stakes to correspond with the records kept by the superintendent, for whose accommodation a lodge has been erected. “The remains of deceased Union soldiers interred in this cemetery comprise all those removed from various localities in East Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and Ashville, [sic] North Carolina, and are as follows:

Number Known: 2,079

Number Unknown: 1,074

Total: 3,153″

It’s hard to tell which secretary of war might have read that report. That year, Lincoln’s combative old cabinet member Edwin Stanton was fired by President Andrew Johnson, an East Tennessee Unionist who was acquainted with this cemetery. It was his firing of Stanton that set off his impeachment proceedings in the U.S. Senate. Following Stanton in the office of the Secretary of War was John Schofield, former Union general involved in some Tennessee campaigns, but he served only for the final months of Johnson’s single term.

By several accounts, the superintendent’s lodge was substandard, in poor repair almost from the time it was built, and badly insulated. The first superintendent obliged to live there was Thomas Ridge, an Irish immigrant from County Galway, likely a refugee from the famine. (His nationality is interesting, by the way; the “sexton” of Old Gray, at the same time, was Irishman Neddy Lavin. It was during the era that the closest population center to both cemeteries was Irish Town, the immigrant community on the north side of the railroad tracks.) Ridge was, in any case, a U.S. Cavalryman, and was claimed to be the first soldier to hold the post of National Cemetery superintendent.

Seeking to make the National Cemetery system more attractive to visitors, the U.S. government contracted with Frederick Law Olmsted, already well known as the designer of New York’s Central Park, and well on his way to becoming America’s most influential landscape architect, for advice on the sudden permanent responsibility. National cemeteries, Olmsted said in 1870, should be planted with trees and shrubs, he recommended, with a wall or fence to keep it decisively separate from the secular world outside. Still, it should be “studiously simple,” in his words, “the main object should be to establish permanent dignity and tranquility.” It should be a sacred spot, Olmsted said, “sacredness being expressed in the enclosing wall and in the perfect tranquility of the trees within.”

***

In 1873, representatives of the New York 79th Regiment, the famous Highlanders, contacted the mayor of Knoxville, who happened to be journalist and Union veteran Capt. William Rule, asking specifically that the graves of their comrades who fell at Fort Sanders and elsewhere be recognized each Decoration Day. As Rule later recalled in his 1900 history of Knoxville, as if it were a moment of considerable significance: “their request was so handsomely complied with and the entire ceremonies on May 30 were impressive and satisfactory to all.”

Attended by thousands, it was an enormous spectacle, perhaps the biggest peacetime event in Knoxville history up to then: a four-block-long parade starting at the courthouse included the German Turn Verein Band, all four fire companies, veterans both mounted and on foot, and a car loaded with women somehow representing each of the 37 states. At the cemetery, the band played a “Funeral March” conducted by its composer, German refugee Gustavus Knabe, a former member of Mendelssohn’s famous orchestra in Leipzig who had directed Union army bands during the war.

The orator was Brig. Gen. Joel A. Dewey, a combat veteran who had served under Gens. Pope, Rosecrans, and Sherman, a colonel of Colored Infantry who had done time in a Confederate prison camp, but now served as a district attorney-general.

Gen. Dewey was only 32 at the time of his speech at National Cemetery, an abstract religious and philosophical rumination on freedom and human rights. “We meet that we may not forget the departed brave–those who met hand in hand with us in the great struggle, but whose forms have vanished, whose voices are hushed….”

Only 18 days after his memorable speech in what may have been the first big commemoration of Decoration Day at National Cemetery, Dewey died. The sudden public death of an apparently healthy young man in the Knox County Courthouse (the same one built by the original owner of the cemetery plot) shocked witnesses, and was ascribed to a heart condition. Capt. Rule, by contrast, would be closely involved with the National Cemetery for more than half a century afterward.

***

In decades to come, a legend spread about a Knoxville woman named Laura Richardson who had an idea that changed how Decoration Day–later to be known as Memorial Day–would be celebrated in national cemeteries across America.

Richardson, originally Laura Catlin, was one of several Connecticut natives who settled in Knoxville in the mid-1800s. As a young woman in 1849, she married a wealthy, twice widowed older man, Marcus de Lafayette Bearden, who was involved in riverboating and local industry. (Knoxville’s Papermill Road is named for one of his ventures, but his politically prominent cousin is the origin of the name of the west-side community.) Bearden was in fact part of the original group that established Gray Cemetery. Laura bore one son, Frank Bearden, before her husband died in 1854.

The widow married a strong Unionist named David Richardson, and though they went north for safety during part of the Civil War, the pair remained in Knoxville after the war was over. She was an admired, resourceful associate of the women’s auxiliary of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), and selected to chair the committee to decorate the graves of soldiers at the National Cemetery.

In late May, 1874, Richardson was disappointed with the flower harvest. In the window of a downtown shop, she noticed bulk rolls of fabric printed with American flags. She bought the rolls, and with several of her fellow volunteers, she clipped the flags out and attached them to 3,500 small sticks cut and sharpened specifically for the job at the Burr & Terry Sawmill. Then, in time for Decoration Day, they planted one flag at each grave.

National Cemetery, circa 1915 showing lags placed by each grave.

Knox County Two Centuries Photograph Project, McClung Historical Collection.

Contemporary records of the event are elusive, though the amount of specific detail included in later accounts argues in the story’s favor. Laura Richardson was indeed a Knoxville resident in 1874, associated with Union commemorations. A story quoted from the New York Times reported she got the wooden staffs from the Burr & Terry Sawmill. There was a well-known sawmill called Burr & Terry’s Sawmill, thriving in 1874–and run by Connecticut transplants like Richardson, not far from National Cemetery. The approximate number of sticks needed, as quoted decades later in New England–3,500–was near the number of graves at National Cemetery that year.

Although she never lived to see it become a universally observed custom, up until her death at age 85 in 1911, in Massachusetts, Richardson believed that she had started the national flag-planting custom out of a combination of necessity, chance, imagination–and, of course, some pretty hard and meticulous work. Her story appeared in a 1915 publication of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association (Massachusetts), written by Rev. Lewis G. Spooner, who presented the society with the late Mrs. Richardson’s handwritten account of the story. (In an aside, without citing sources, Spooner claimed the flag-planting tradition had older precedents in the north–but he was too young to remember that era personally, and Decoration Day was still new at the time of Richardson’s innovation.)

Richardson’s make-do gesture may not have caught on dramatically, at least not right away. For many years after that legendary innovation, Decoration Day continued to be celebrated mainly with lowers in Knoxville, with only occasional mention of flags.

In 1878, the cemetery had begun to be such an attraction on Memorial Day that its supporters built a permanent rostrum, perhaps like a gazebo, in the northeastern section of the cemetery, to support brass bands and speakers.

An 1896 newspaper story mentioned that the rostrum was “called into service every 30th of May by the GAR, who assemble on that day to pay tribute to their dead comrades by placing flowers and flags on their graves.”

By the time flag-planting became a national standard in the 1930s, supplanting flowers, Laura Richardson’s charming and plausible story was becoming well known, noted in at least a few national publications.

***

Civil War burials might have been assumed to be completed by the 1870s, but in 1884, the National Cemetery received an unusual case. Union veteran John Hughes had been “an inmate of the insane department of the County Asylum for the poor.” He was first buried near that institution, in what was probably a pauper’s grave.

When it was discovered that the unfortunate had been injured in the explosion of the riverboat Sultana, an Officer Hicks ordered that he be buried at National Cemetery. The still-mysterious Mississippi River disaster of April, 1865, killed the majority of the overloaded Sultana’s 2,000-plus passengers. Most of them were Union veterans who, recently freed from Confederate prisons, thought they were on their way home. Around 200 victims were from East Tennessee; they’re memorialized with an unusual monument featuring a sculpted representation of the ship at Mount Olive cemetery in South Knoxville.

In the Twentieth Century, Memorial Day ceremonies included dropping wreaths into the Tennessee River from the Gay Street Bridge, in memory of the victims of the Sultana, often involving a walk, or march, to National Cemetery afterward, often including stops at the courthouse and the Doughboy Statue at Knoxville High on the way. Although the Sultana was forgotten in much of the country, it was remembered by name during Memorial Day ceremonies in Knoxville for decades.

Every Unknown has a different story. One turned up not far from the cemetery itself.

Every Unknown has a different story. One turned up not far from the cemetery itself.

In 1889, Superintendent James McCauley, who served the post for four years (a relatively short interim in Thomas Ridge’s long occupation of that office) heard a report, based on memories, that a Union soldier who had died in Confederate custody had been buried along Second Creek, just north of the National Cemetery. Digging at the indicated site, they found a skeleton and five brass buttons. “The remains were taken to the National Cemetery and re-interred. Nothing was found to establish the name of the soldier. The ladies say he was an Ohio man and the probability is that he was captured somewhere in North Alabama, in the neighborhood of Huntsville or Decatur….”

***

The Civil War had been such a horror that the United States avoided war for more than three decades, with the exception of limited actions against Native Americans tribes in the West. During that long period, National Cemetery was considered mainly a Union soldiers’ and veterans’ cemetery. Meanwhile, Knoxville quadrupled in size in the 20 years after the Civil War, with much of the new residential growth on the north side of town, much of that in the vicinity of National Cemetery, which no longer seemed to be on the fringe of the pastoral countryside.

Just about one quarter mile to its northwest, Brookside Mills, one of the largest textile mills in regional history, began weaving fabric, with well over 1,000 employees in 1885. Almost all Brookside employees lived within walking distance of the factory, many of them near the cemetery. The downtown section known as Happy Holler began developing as a cluster of saloons and stores. The area just to the east and north of National Cemetery became a densely developed suburban residential neighborhood, so popular that by 1888 it incorporated as its own town, North Knoxville. It existed as a “city” with its own government for nine years before being incorporated into the growing city of Knoxville in 1897. Today, what remains of North Knoxville mainly comprises two reviving neighborhoods: Fourth and Gill, a few blocks to the east of the cemetery, and Old North, a few blocks to the north.

The Fountain Head Railroad Company, which ran the locally legendary “dummy line”—a small steam train on a streetcar track–to Fountain City, obtained permission to run a line up “Holstein Street” (aka Holston, later known as Tyson), from Broadway to Munson (now Bernard) to serve the National Cemetery. Still, until 1897 the National Cemetery still lay outside of Knoxville city limits, meaning that funding for modern paved roads was limited.

In 1886, the U.S. Senate passed an act with specific terminology to make Knoxville’s National Cemetery more accessible. It made plans for a road then known as Holston (Tyson) to connect Broadway to Munson (Bernard). As the legislation made clear, “said cemetery lies outside of the city of Knoxville, and in a locality where it will be many years before the city authorities will be able to, or find any necessity for, improving the roads now designated as streets leading to said cemetery, and the present condition of said approaches makes it both difficult and disagreeable to visit said cemetery to pay the tribute of respect to the nation’s dead on Decoration Day and other appropriate occasions.”

During the Blue-Gray Reunion of 1890, thousands of veterans from both sides of the Knoxville campaign 27 years earlier returned to a city that was almost unrecognizable from the rough village they’d attacked or defended, now with theaters and streetcars and telephones and electric lights. Hundreds of Union veterans attended this unusual party that included former Confederates; among the attractions was a fireworks show over the ruins of the old fort. National Cemetery got special attention in promotional material as a site to visit. That week, after Fort Sanders itself, National Cemetery may have been Knoxville’s chief tourist attraction.

During the Blue-Gray Reunion of 1890, thousands of veterans from both sides of the Knoxville campaign 27 years earlier returned to a city that was almost unrecognizable from the rough village they’d attacked or defended, now with theaters and streetcars and telephones and electric lights. Hundreds of Union veterans attended this unusual party that included former Confederates; among the attractions was a fireworks show over the ruins of the old fort. National Cemetery got special attention in promotional material as a site to visit. That week, after Fort Sanders itself, National Cemetery may have been Knoxville’s chief tourist attraction.

Those visits likely had some results, in terms of raising awareness of the National Cemetery among veterans, who, visiting it for the first time, likely noticed gaps in the cemetery’s memorials. In May, 1891, just a few months after the reunion, a new, non-regulation stone appeared at National Cemetery. It memorialized two Union defenders of Fort Sanders, killed in the Confederate charge almost three decades earlier. Isaac Garretson and Aaron Templeton were 22 and 25 years old respectively.

“Erected by surviving comrades,” it reads.

This project was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Afairs’

Veterans Legacy Program through the University of Tennessee.