National Cemetery

A SHORT HISTORY – PART I

< CEMETERY IMAGE GALLERY >

A selection of photographs by Shawn Poynter and KHP taken at Knoxville’s National Cemetery.

Please note: This short history is spread over four parts. Follow the navigation links at the foot of the page to continue.

INTRODUCTION

Knoxville’s National Cemetery offers a bright, orderly contrast to everything around it.

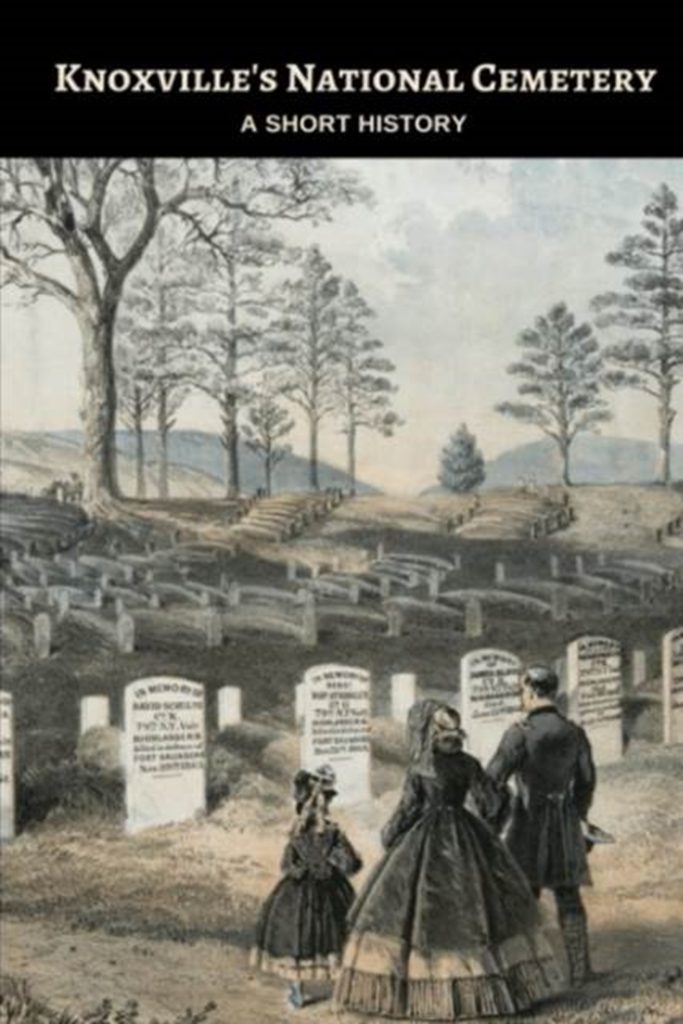

Written by Jack Neely, and published by KHP, the book received a historic preservation award by Knox Heritage in 2018.

It’s the final resting place of several thousand men and women, black and white, who in a wide variety of circumstances, signed up to serve their country in uniform. Some of them died as aged veterans; many others were young soldiers who died in combat.

On a sunny day, its white marble stones almost glow amid the bright green grass, as the United States flag flies high above it all from a tall pole in the center. Compared to much that surrounds it, the cemetery looks almost modern. In fact, it’s more than 150 years old. It was founded as an urgency of North America’s most violent war.

https://www.knoxvilleweekend.com/knoxville-chronicles-knoxville-national-cemetery/

This region’s role in the Civil War was in several respects unusual. At the same time, the region was emblematic of the whole war, and experienced much of its drama and tragedy. The National Cemetery reflects that chaos, while offering a visual antidote to it.

These ten acres memorialize the American dead of every war in the last 155 years: the Civil War, the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Begun as a practical exigency of war, in the days when the Union dead arrived in mule-drawn wagons, and the city was expecting a siege of Confederate troops, it was intended to be a final resting place for soldiers who lacked the resources to be buried elsewhere–and, in fact, hundreds of those buried here lacked even identities, many of them buried under slabs marked UNKNOWN. In the last century the National Cemetery has become a place of honor, where veterans of means often prefer to be buried, regardless of their wealth, fame, or rank, among their comrades in arms.

Today, more than 9,000 soldiers (and, in some cases, close family members) are buried here, almost three times as many as were buried here during the last war on American soil.

Today, a walk around National Cemetery tells a distinctly American story.

A BURYING GROUND

Founded at the dawn of the Republic, Knoxville was the birthplace and first capital of Tennessee, home to territorial Governor William Blount, a signer of the U.S. Constitution, and to Revolutionary War hero John Sevier.

As the new state filled out to the west, Knoxville lost its state-capital status, and stagnated for some years with no very obvious purpose. With the arrival of railroads in the 1850s, Knoxville reinvented itself as an industrial center, attracting business and new citizens by the thousands. By the time the Civil War began, Knoxville was a rapidly growing small city dominated by newcomers, from the North, from the Deep South, and from overseas.

For more than sixty years, most of Knoxville’s business and daily traffic had remained clustered on the river bluff where the city was founded. Early Knoxvillians showed little interest in the low-lying areas north of town, parts of which were swampy. However, the arrival of two important railroads in the 1850s created new interest on the north side of town, bringing the city new economic life. Knoxville began stretching in that direction.

Just before the Civil War (1861-1865) broke out, small factories were springing up along the railroad routes, between what’s now Depot and Magnolia, and along Second Creek. The city laid out new streets north of the old business district. It attracted newcomers, especially Irish immigrants, who formed their own cohesive community known as Irish Town.

One of the biggest landowners on the north side had once been a colorful figure in antebellum Knoxville. Originally from Virginia, John Dameron carved a niche for himself in the very specialized field of designing and building county courthouses. He provided several for East Tennessee and Western North Carolina. His 1836 Knox County courthouse was perhaps his first, a three-story domed, columned, “temple of justice” on Main Street. (The predecessor to the 1886 courthouse still used today, Dameron’s was directly across the street.) Employing a crew of skilled slaves to make the brick, from red clay found near the site, they built the courthouse that served the county for about fifty years.

That courthouse was demolished over a century ago; Dameron’s name is better remembered northeast of Knoxville in Rogersville–where the Hawkins County Courthouse and other historic buildings of the 1820s and 1830s are rare survivors of his business.

By a family account, it was Dameron’s success building the Knox County Courthouse that provided capital to purchase dozens of acres on the yet-to-be-incorporated north side of a town he believed was on the verge of growth. His wife was skeptical of his purchase, remarking ruefully that “you’ve just bought a very poor farm.” He countered that Knoxville’s future growth would prove it to be a profitable purchase.

His family was associated with the area for some years. His name (sometimes recorded as Damron) is the source of nearby Dameron Avenue. One of his daughters married a Wray, the likely origin of Wray Street, which connects Dameron Avenue to the National Cemetery.

One of Dameron’s first sales was to the Gray Cemetery organization. In 1850, leading citizens of Knoxville, confident of the city’s imminent growth, purchased fourteen acres of rural forest land to establish the small city’s first general-purpose graveyard. The design, deliberately asymmetrical, following the contours of the land with meandering lanes, reflected the ideals of the international “Garden Cemetery Movement” to make cemeteries beautiful, attractive places that would make for an interesting stroll.

Gray Cemetery’s name came at the suggestion of a daughter of a statesman and wife of a university president, Sarah Cocke Reese, who hoped the graveyard would evoke the pastoral images of a favorite poem, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” by English poet Thomas Gray. The cemetery was familiar and well established by the time of the Civil War, and became the burial place for hundreds of

prominent soldiers and statesmen of both sides of the conflict. Their burials were paid for by their local families. Some could afford burial at Gray Cemetery; many could not.

Knoxville was just blooming as an industrial center when the Civil War all but killed it. The city was divided in its sympathies, with more than two political factions – but perhaps the largest number of loyal Unionists, soon to be known as Republicans, in any Southern city.

Spurring the city’s loyalties was William G. “Parson” Brownlow, editor of the Knoxville Whig. His colorful anti-Confederate rhetoric caused him to be burned in effigy as far away as Texas, while he was invited to speak to cheering crowds in Northern cities.

Despite Tennessee’s ultimate alliance with the Confederacy, Knoxville remained the population center of a Congressional district that somehow retained its seat in U.S. Congress.

However, the city was home to many powerful secessionists, too–as well as many others, hundreds of them new to the region, who, unsettled by the war, merely hoped it would be over soon. Knoxville struck some as an unstable place, and many were grateful to find opportunities to leave the city.

As a result of the horrific demand for large numbers of burial spaces after the Civil War’s first year–three months after the bloody Battle of Shiloh–Congress passed an omnibus bill on July 17, 1862 that included a new idea in American history, a provision that the president could “purchase cemetery grounds and cause them to be securely enclosed, to be used as a national cemetery for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country.” At the time, Knoxville was securely in Confederate hands, and the dictates of the U.S. government were of little concern.

Confederate troops occupied Knoxville early in the war, eventually jailing Parson Brownlow. Pro-Union saboteurs were publicly hanged in downtown Knoxville. It became obvious to Union authorities during the Civil War’s first year that the sheer number of dead, already in the tens of thousands, would be far beyond the worst predictions, worse than any war in American history. Among its many other challenges, the nation would face an unprecedented demand for burial spaces.

THE HONOR DUE A BRAVEMAN

Occupying Confederates fended off a cavalry attack by Col. William Sanders on June 20, 1863. Sanders’ artillery lines were along modern Fifth Avenue, on the city’s northern edge. That day the future site of the National Cemetery came close to becoming a battlefield, itself.

The skirmish cost lives of both Confederates and Union men, including some civilians. But a little more than two months after defending the city from the Union attack, the Confederates evacuated the city to assist in the Chickamauga campaign to the south. In early September, 1863, Gen. Ambrose Burnside occupied the city without bloodshed, surprising Confederate authorities, who the following November orchestrated a plan to retake Knoxville.

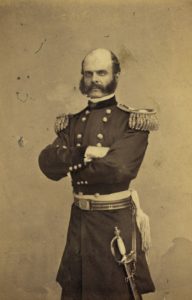

Burnside was by then one of the Union army’s more famous commanders, but perhaps better remembered for his distinctive whiskers than for his strategy. Still in his thirties when he was promoted to major general and given charge of the Army of the Potomac, he had fought to a stalemate against Gen. Lee’s army at Antietam and made choices that proved costly and tragic at Fredericksburg.

A few months later, he found himself in charge of the invasion of East Tennessee. Here, he redeemed his reputation. Burnside was an Indiana native who settled in Rhode Island, but unlike most Union commanders, he had a deep affinity for the South. His family had roots in South Carolina, where his father grew up.

During his fall in East Tennessee, as he and his chief engineer, Capt. Orlando Poe, planned an extensive network of defenses, Union troops were dying in skirmishes elsewhere in East Tennessee, both in battle and of disease. Knoxville, the region’s population center with rail connections, seemed a logical place for burials. When the inevitable need for a soldiers’ cemetery emerged, the site choice may have seemed obvious. Knoxville area’s best-known cemetery, Gray Cemetery, later known as Old Gray, was already an attraction in 1863. As Burnside and his officers noticed upon their arrival, there were several undeveloped flat acres on higher ground along Gray’s northern edge.

By some accounts it was within only a couple of days of his arrival that Burnside first eyed this spot, just under ten acres and barely beyond Knoxville’s northwestern city limits, as a place for burials of the Union dead, even if the new term “National Cemetery” didn’t immediately come to mind.

Burnside’s acquisition came by way of the rules of war, without the consent of the landowner. John Dameron, now in his mid-sixties, was living on a plantation near Charlotte, North Carolina. His courthouse-building business had depended on slavery, and he was not necessarily sympathetic to the Union cause. (Dameron could hardly have guessed at the career of a great-nephew–born in 1864, during the war. The younger relative was Thomas Dixon, the popular novelist who in the 1890s romanticized the Confederate cause and even the Ku Klux Klan; his novel The Clansman inspired the controversial 1915 film, Birth of a Nation.)

The land Burnside acquired for the new federal cemetery amounted to “about ten acres” (9.83 acres, to be precise). A legal judgment in U.S. District Court in Knoxville, after the war, in March, 1867, when it was already the site of more than 2,000 burials, affirmed the U.S. government’s purchase of the land.

It was barely beyond Knoxville city limits, which formed the boundary between Gray and the new federal cemetery – which was, literally, out in the country. Knoxville became the site of the region’s primary Union hospital, located at the old Deaf and Dumb Asylum, barely half a mile to the southeast of the new cemetery site. “Asylum” in those days connoted “refuge.” It was really the original Tennessee School for the Deaf, a nationally known institution, and one of Knoxville’s largest and sturdiest structures. It was first requisitioned as a hospital by Confederate forces, but became a formal Union hospital, with staff surgeons, nurses, and orderlies, for the last nineteen months of the war.

The Confederates moved their institution to Georgia, but, accustomed to the name, kept calling it the Asylum Hospital. So, for several months, both sides had military medical facilities, each called the “Asylum Hospital,” in different states but named for the same building in Knoxville. Although many Union soldiers recovered there, many did not. Their bodies were loaded onto horse carts for the short ride to the new soldiers’ cemetery.

Burnside’s esteem for the Union dead is obvious in his choice of names for the new Union fortifications, most of which were named for Union officers who fell in the East Tennessee campaigns.

The urgency to establish a cemetery so soon seems to have been a personal response to one particular soldier’s remains.

Private Orville Hosford, of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry, had been part of Colonel William Sanders’ daring raid on Confederate-held Knoxville three months earlier. He was so severely wounded that Sanders left him behind to be cared for by the Confederates. Hosford died a few days later. With no friends in town, and no organization to object, Hosford was buried in the “county cemetery”–Knoxville’s “Potter’s Field,” for paupers. Perhaps it was Sanders himself—now recommended by President Abraham Lincoln for a promotion to brigadier general–who remembered Hosford, and thought the Ohioan deserved a proper soldier’s burial.

According to the Knoxville Daily Bulletin of September 7, 1863, “His remains having been discovered in the county cemetery, his comrades disinterred them and gave them the honor due a brave man and a true patriot.”

Hosford soon had company. Nine days later, and still within the first two weeks of Burnside’s occupation, the same newspaper remarked, “Recently the soldiers have been removing the Union dead from the county burying ground and reinterring them in Gray Cemetery near the grave of Private Hosford, whose remains were removed there last week. Nearly fifty graves have been removed so far and placed on the crown of the hill at the new cemetery.”

That paragraph refers to the site loosely as “Gray Cemetery” because there was no obvious distinction at the time, and no other name to use. These new soldiers’ graves were in the Gray Cemetery area, but just beyond it, with no wall or fence to divide them. The same paragraph calls it “the new cemetery,” a phrase that couldn’t apply to the familiar part of Gray, then 13 years old. The modern National Cemetery lies at a

higher elevation than most of Old Gray, and can be described as “the crown of the hill.”

So as the cicadas of late summer droned, and as soldiers labored all around the city urgently building earthworks to defend Knoxville from the expected Confederate assault, at least a few were hard at work on the priority of properly burying their comrades from previous campaigns, and christening a new military cemetery.

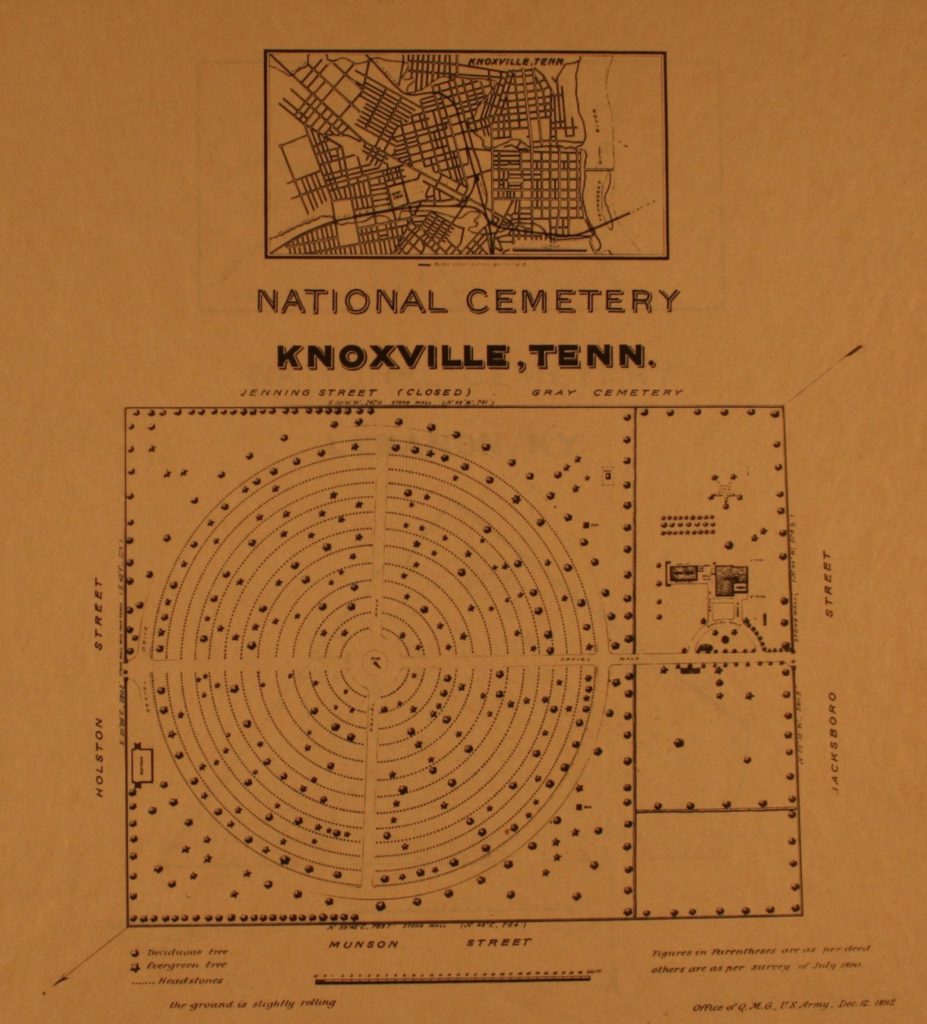

The new burial ground arrived with one surprising feature. Although at least two other National Cemeteries in Northern Virginia, at Richmond and Petersburg, were employing the concentric-circle design by the end of the war, Knoxville was one of the earliest. The “wagon-wheel” design, as it was known, was agreeable to the eye, but also had a practical inspiration. A long string could be attached to the central flagpole to assist with laying out graves in perfect symmetry.

By some long-cited government accounts, it was Burnside’s assistant quartermaster, a Capt. E.B. Chamberlain, who was in charge of the project, and who came up with the concentrically circular design. However, no Union officer with those initials appears in handy contemporary accounts, including the Official Records of the war.

By several accounts, Burnside’s divisional quartermaster was Capt. Hiram S. Chamberlain (1835-1916), an Ohioan of 28 when he arrived. It’s an important distinction, because H.S. Chamberlain became a significant figure in Knoxville history. He’s often cited in accounts of the war as the officer who received prominent secessionist Joseph Mabry’s surprising pledge of loyalty to the Union. After the war Chamberlain, whose home was just north of Cincinnati, settled in Knoxville, the city he first visited with an occupying army.

He became a major leader of industry in the city, founder of Knoxville Iron Works (whose “Foundry” still stands in World’s Fair Park, hardly half a mile south of the National Cemetery) and even an early promoter of civil rights, touring to promote the work ethic and economic independence of the blacks who had worked shoulder to shoulder with whites in his factories. He later moved to Chattanooga, where he became even more prominent in industry. An 1896 newspaper description of Knoxville’s cemetery states that it was “founded in 1863 by Captain Chamberlain of Chattanooga as first quartermaster.”

But Chamberlain may not have been the actual designer. In 1900, journalist and veteran William Rule– who probably didn’t witness the cemetery’s establishment, but was much involved in its evolution afterward–remarked that it was “laid out according to plans from Washington.”

It was not referred to right away as a “National Cemetery,” but it would be known by that phrase before the end of the war.

Most of the early burials were those of Union enlisted men who fell in East Tennessee campaigns, but among them were several notable officers, like Capt. Joel P. Higley, of Ohio, who was killed in action at Blue Springs, near Lebanon, on Oct. 10. He died at age 38, certainly unaware that he would soon be the honoree of a tiny fort in an unfamiliar city. Fort Higley was a two-cannon redan that strengthened the Union defenses of the city on the critical bluffs south of the river.

Today it’s one of the two best-preserved Union earthworks in the Knoxville area. After being threatened by development pressure, it became the centerpiece of the Aslan Foundation’s public project, High Ground Park.

Burnside honored fallen officers in his East Tennessee campaign to distinguish the small forts and batteries that ringed Knoxville by the end of November, 1863.

Other fortress honorees interred at National Cemetery include Lt. William H. Stearman, for whom Battery Stearman, on the northeastern part of town, was named. Stearman was killed near Loudon in the early days of the siege of Knoxville. Frank Zoellner (or Zollner), and Lt. Charles Galpin, both members of the 2nd Michigan, died in a Nov. 24, 1863 attack on rebel positions near Fort Sanders. Just after their deaths, a gun emplacement just northeast of Fort Sanders, along what’s now Western Avenue, became Battery Zoellner; and a fortification on Summit Hill (previously Gallows Hill), overlooking the train tracks on the north side of downtown, became Battery Galpin. Today, there’s no known trace of these three small fortresses except on old military maps.

Their honorees are buried at National Cemetery alongside men whose only memorials were slabs just like theirs.

In 1863, of course, military cemeteries were reserved mainly for soldiers, whether known or unknown, but mainly those who didn’t have obvious family on hand to bury them in a more traditional family plot, churchyard, or private cemetery.

Most officers were buried in private cemeteries, and that was the case with Brig. Gen. Sanders – who died in the Lamar House downtown, and was buried, at first secretly, at night in the Second Presbyterian churchyard a few blocks away. When that churchyard was commercially developed, 40 years later, Sanders seems to have been reinterred about 100 miles away, in the National Cemetery in Chattanooga. At least, that’s the location of a marker with his name on it. Why he was moved there is something of a mystery.

As soon as Sanders’ death was revealed in the nervous and almost surrounded city, it was applied to the Union Army’s largest fortification, on the west side of town. Fort Sanders, or Saunders, as it was often misspelled both in Army and newspaper reports, withstood a major pre-dawn charge by Longstreet’s Confederates. The Battle of Fort Sanders constituted the fiercest fighting in Knoxville-area history, and was such a decisive Union victory that Longstreet lifted his siege and offered his resignation to

Gen. Lee, who rejected the offer and sent Longstreet back to the front in Virginia.

The Confederates had lost 129 dead on the battlefield in only twenty minutes—not counting hundreds wounded or captured during that horrible moment. Only eight Union soldiers died in the assault, members of the proud 79th New York Volunteers, the “Highlanders.” Several of them would soon be buried at the new National Cemetery.

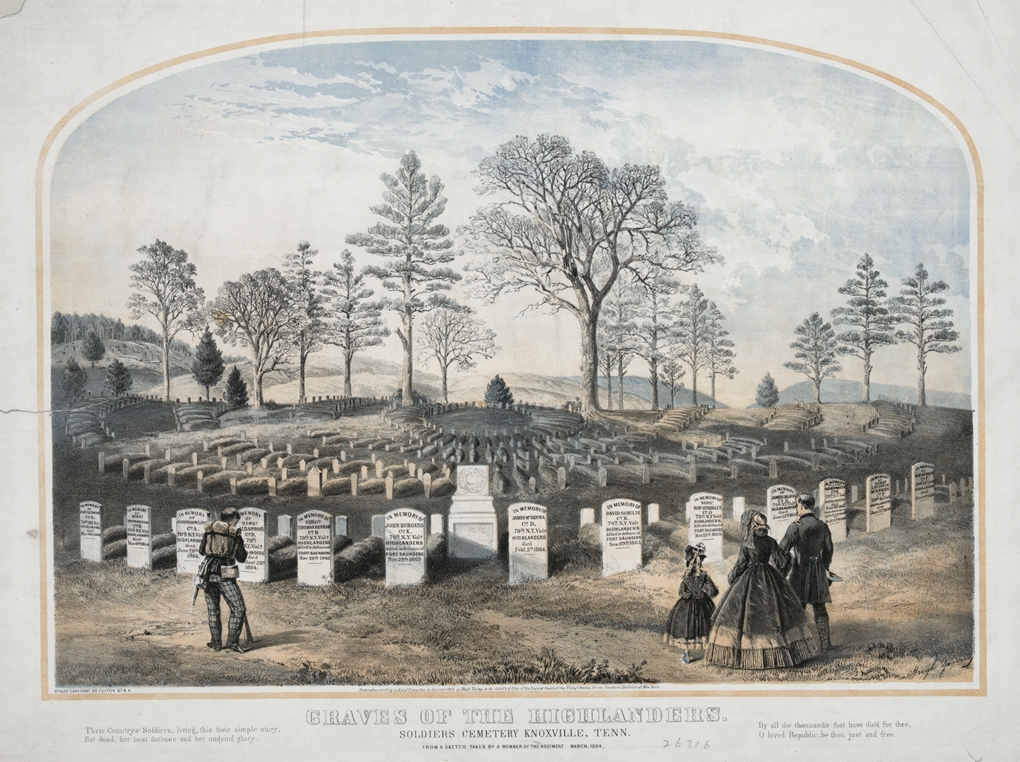

This romantic image of the National Cemetery, depicted when the Civil War was still underway, shows a series of real graves as they still appear in the cemetery’s inner circle–though in backwards order, as if the artist reversed the side of the grave on which the soldiers’ individual names appear. It’s possible that this depiction shows painted wooden graves, and that when the permanent marble graves were installed, the inscriptions appeared on the opposite sides. Library of Congress.

Knoxville was securely occupied and fortified in August, 1864, when a military newspaper, the Army Mail Bag, refers to the new military burial ground as the “Knoxville Cemetery” in a poetically quotable passage:

“Wonder, courteous reader, if you ever visited the Knoxville Cemetery with gay company to talk on grave subjects? We have. We went Wednesday, August 10th, 1864.

The hours of our choosing were those of the afternoon, the heavy clouds having cleared away, leaving fragments of rainbows floating fantastically through the sky, like the fleecy cloud visions of a young life….

Our line of march was by the Asylum Hospital, from which so many martyrs have been borne to the burying ground, that the ambulance horses keep stately step to the dead march and quicken their measured tramp when, while returning, the band plays, ‘And we sent him to the happy land of Canaan.’ …”

That passage affirms the grim association of the cemetery with the Asylum Hospital. Built between 1848 and 1851, that building still stands today, overlooking the intersection of Henley Street and Summit Hill Drive, serving the Lincoln Memorial University School of Law.

“How desolate!’ exclaimed the pedestrian, “as we passed several mounds of ashes, brick and broken fragments of houses burned down during the siege. A sad contrast between domestic tranquility and war’s unsparing devastation. Passing on to Gray the cemetery, we discovered little or nothing to break the oppressive desolateness, no fresh-strewn flowers upon the unfenced tombs, nor wreaths of affection to fling a faint gleam of love’s sunshine through this lonely abode of shadows…. After strolling through the

cemetery and paying the soldier’s circle especial admiration, ’twas pensive but not unpleasant to sit in the sad shade and reflect how gloomy seems the grave when no token of tender regard from the living gives proof that they gratefully remember the departed.”

The description of ashes and broken fragments of buildings is interesting. Deliberate arson was not part of Union or Confederate strategy in Knoxville, and the city didn’t see the degree of destruction witnessed in several Southern towns. But there are other vague references to houses burned down during the war on the north side of town, along the north side of the railroad corridor. And is that reference to the “soldiers’ circle” the first published mention of Knoxville National Cemetery’s unusual design?

A month later, on September 17, 1864, the Army Mail Bag describes how large the cemetery had become, in its first year. That article also provides several early references to its proper name, if a little inconsistently. “Up to the present time about 1,475 bodies have been buried in the National Soldiers Cemetery. It was established sometime in September 1863.”

In the war’s final year, with Knoxville apparently secure from Confederate invasion, U.S. Colored Troops formed a large part of the city’s occupation forces. It was extraordinarily unusual anywhere in the United States to have armed blacks with some authority over whites, and friction between the Colored Troops and civilians occasionally resulted in injury or death.

***

Second Creek, one of the city’s principal water sources during the era, runs just about 400 feet west of the cemetery. The combination of the railroad and Second Creek attracted business, notably one of Knoxville’s first beer manufacturers, the Union Brewery. Whether its name bore any relation to the Union cause, the Union Brewery thrived just after the Civil War, advertising its fresh ales and lagers, noting its location near the cemetery, which was still a bit off the beaten path.

As the war ended, most or all of the National Cemetery’s graves were marked only with numbered stakes, later to be wooden planks with names painted on them. The cemetery evolved with influences both locally and from Washington. In 1865, the Quartermaster was administering the Federal Reburial Program, with orders to recover and identify as many Union soldiers’ remains as possible. The following year, Secretary of War Stanton issued an order to “secure suitable burying places in which [soldiers] may be properly interred; and to have the graves enclosed so that the resting places of the honored dead may be kept sacred forever.”

When the National Cemeteries first began burying fallen soldiers in the 1860s, temporary stakes and wooden grave markers were used, as shown here at the Soldiers’ Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia. The National Cemetery in Knoxville likely later replaced initial wooden grave markers with the white Vermont marble gravestones. Library of Congress.

But it was not until the National Cemetery Act of February 22, 1867, that it was all official. That legislation offered funding for perimeter walls, fencing, planting, and lodging for superintendents who were expected to live on the property of the cemetery. A twenty-four hour attendant helped discourage vandalism, in an era when former Confederate sympathizers sometimes disrupted Union veterans’ parades. (Partisan violence broke out in Knoxville as late as the 1870s.)

By several accounts, however, it was a shack, “very badly built,” according to an 1869 report, “the plank is not seasoned, and the shingles were most inferior.” Quality was more a priority in terms of the stones used to memorialize the dead. Federal legislation specified that gravestones should be fashioned from Vermont marble. Although in the post-Civil War years, Knoxville was becoming one of the nation’s leading marble producers–and local marble is used for markers and monuments in most local cemeteries, especially Old Gray–Vermont marble has a reputation for being harder, more durable, and more uniformly white, than Tennessee marble. Army specifications have assured that Vermont marble is what has been used in National Cemeteries.

Many of these markers say “UNKNOWN.” The remains of tens of thousands soldiers who died in the Civil War were never identified. According to a report of burials in the seventy-three National Cemeteries in 1870 America–including Knoxville’s–only 58 percent of graves were connected with the name of a soldier. In Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New York, the families of these men perhaps heard that their husbands, fathers, brothers were missing–but never learned that they were buried in Knoxville.

This project was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Legacy Program through the University of Tennessee.