National Cemetery Part III

A SOLDIERS MEMORIAL

Of all the National Cemetery’s stories, that of the Union monument may be the strangest.

Perhaps wisely, neither Confederate or Union factions had ever had the temerity to erect a partisan monument in a high-traffic area of Knoxville–certainly not downtown, when arguments about the war sometimes led to street violence and even murder.

On the courthouse lawn, defended by no ornamental cannons, a memorial to Revolutionary-era pioneer John Sevier rose in the late 1880s, in the form of a tall marble obelisk. No one alive remembered Sevier, and as a gesture in stone, it was a safe one.

In postwar Knoxville, Unionists had been more numerous and generally more prosperous than their former opponents, but Knoxville-area Confederates became the first to erect a major statue as a memorial to their dead. It stood in the secluded, mostly unmarked Confederate cemetery on the east side of town. A marble shaft with a bold, defiant-looking rebel soldier on top, it went up over a mostly unmarked Confederate graveyard in May, 1892–leaving Union sympathizers wondering why they hadn’t come up with something similar for their larger, more prominent cemetery.

According to Captain Rule, the monument effort began with a committee meeting in Athens, Tenn., including members from Nashville, Chattanooga, Greeneville, and other Tennessee cities. The proposal reportedly originated with Col. H.C. Whittaker of New Market. Rule was the only Knoxvillian in the group, and it may be a testament to his persuasion that the committee agreed that a state Union monument should be in Knoxville.

In Tennessee’s state government, where the dominant Democrats had begun to romanticize the Confederacy, were unlikely to approve funding for a Union monument. Furthermore, the soldiers of the war were graying, many of them passing.

Union Generals Burnside, Sherman, Grant, and others who had led the East Tennessee campaigns of 1863 had already died, as had the intrepid Parson Brownlow. Even the brilliant young engineer of Knoxville’s defense, Captain Orlando Poe, died in 1895.

On July 4, 1893, the GAR announced an ambitious fundraising effort. It was slow going.

“How the Big Monument Looks”

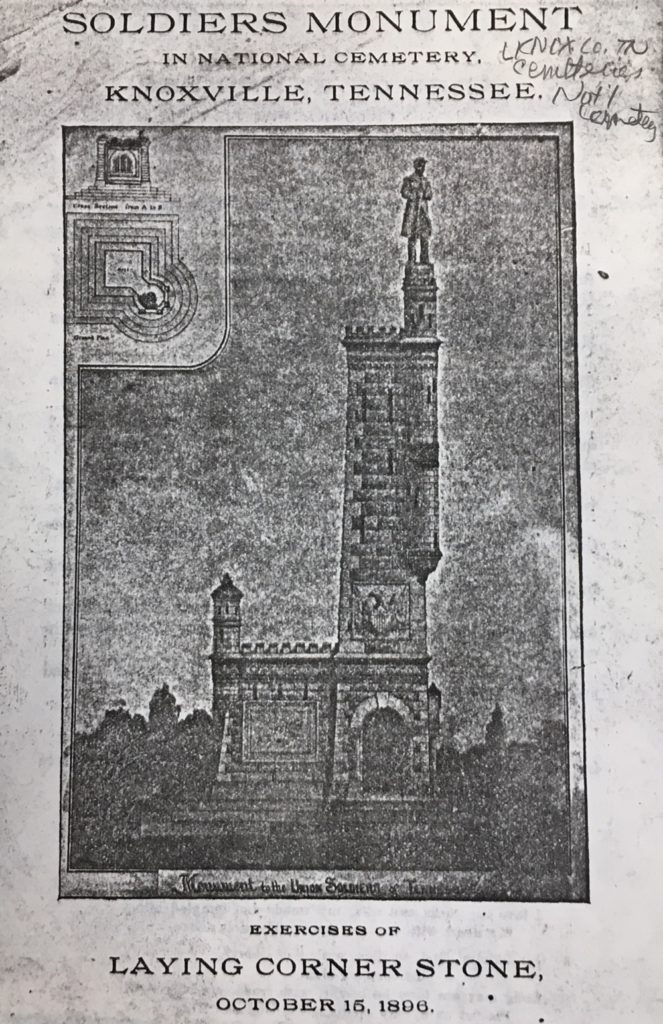

An early promotional lealet shows a memorial that was very slow to get of the ground ater the

laying of the cornerstone in 1896. This early sketch pictures a soldier on top, nothing like the

monument as it was completed five years later–but very similar to how it was rebuilt in 1906. McClung Historical Collection.

They laid the cornerstone three years later, with an oration by Gen. Gates P. Thruston, Ohio-born veteran of Shiloh, Stones River, and Chickamauga–who had become noted after the war as a Nashville lawyer, and as an author on prehistoric Native American culture as interpreted from archaeology.

An 1896 Knoxville Morning Tribune story describes the cemetery as it was: “situated upon a swell of land, sloping from the center in all directions, but more sharply to the west…it is enclosed by a good rubble stone wall laid in mortar coped with slabs four inches thick, and is four feet, eight inches high.”

At the time, the main, formal entrance was at the bottom or the western slope, what was then Jacksboro Pike (now Cooper Street), which then connected cleanly to downtown. But there were also two entrances on Holston (now Tyson), one for horses and carriages, one for pedestrians.

A committee of Union stalwarts, among them Parson Brownlow’s old associate in journalism, William Rule, himself a Union captain, tried to get something going.

Although it was in Knoxville, it was to be a statewide memorial. However, after a strong start, fundraising dwindled. A design for a castle-like monument with a Union soldier’s statue on top was approved by the U.S. Quartermaster’s Office in 1896—but with the disheartening proviso that no federal funds would go to support it.

A grand laying of the cornerstone in 1896 was an occasion for speeches and patriotic anthems, but little more than that. That cornerstone was a lonesome oddity for several years.

In 1897, the National Cemetery’s neighborhood was annexed into the city, and drawing unaccustomed attention from municipal authorities. It was now, formally, in Knoxville proper. The same year, the GAR insisted that Tennessee’s eight thousand Union pensioners should each donate at least one dollar to the effort. That turned out to make the bulk of the need.

It would be no ordinary monument, but reportedly “the only monument to the memory of Union soldiers in the entire South,” except for those in military parks and one in a national cemetery in New Orleans.

Things had begun stirring in 1898, when an unexpected war captured the nation’s attention.

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

With the mysterious explosion of the Maine in Havana Harbor, the United States went to war with Spain, and Knoxville suddenly became a training area for soldiers bound for Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines in the Spanish-American War. Thousands of soldiers arrived from locations all around the eastern United States. Barracks are notorious breeders of germs, and during a four-month period fity-nine soldiers died in Knoxville, most of an ongoing epidemic of typhoid fever. Thirteen of those recruits who died in camp before ever making it to a battlefield were buried at National Cemetery.

The military hospital was located along Broadway, less than a mile from the cemetery. East Tennessee lost scores of men in that short war, but some would be better remembered than others. Two were memorialized with a ceremony at the University of Tennessee later that year for their coincidental deaths.

Henry L. McCorkle grew up on a farm in Hawkins County, but came to Knoxville to go to UT. After graduation in 1891, bored with a businessman’s life, he joined the Army. A personal recommendation from an unlikely source, 80-year-old Isham Harris, the secessionist governor who led the movement to ally Tennessee with the Confederacy–but who later served as a prominent U.S. senator–helped get McCorkle a commission as lieutenant.

Born in California, John Jay “Jack” Bernard had a very different upbringing. Son of an Army general, Reuben Bernard, notable for his role in the arrest of the Apache Chief Cochise, Jack grew up riding horses with his father’s mounted company across the still-Wild West, from South Texas to the Dakota territory. Gen. Bernard had lived in Knoxville as a young man, and John attended the University of Tennessee, majoring in chemistry, but then joined the Army on his own, out West again, serving in the Cavalry.

Both McCorkle and Bernard were first lieutenants, and both had been members of some of the same groups at UT, like the YMCA and the Philomathesian Literary Society, but McCorkle graduated just as Bernard entered, and there’s no indication the two knew each other well. They were in different regiments in Cuba. But they died near each other the same day, among the 81 American losses at the fierce Battle of El Caney, on July 1, 1898, just as Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders famously charged up San Juan Hill.

Both were buried at National Cemetery, side by side, under two very different non-regulation monuments. El Caney appears in some other inscriptions in National Cemetery.

A rare photo of soldiers on Gay Street during the Spanish-American War. During that short conlict in

1898, Knoxville hosted training bases for recruits from all over the nation. Several of them died of a

typhoid outbreak, and are buried at National Cemetery. Others were killed in combat, from Cuba to the

Philippines, and were returned here for burial. In this photo, the most prominent building in the

background is the Imperial Hotel, which burned down in 1916–to be replaced by the Farragut, an

homage to a Knox County native who became the U.S. Navy’s first admiral. “Photographs of Tennessee

Cities Collection, MS.0951. University of Tennessee Libraries, Knoxville, Special Collections.”

As the short war came to a close, America’s national-cemetery system was generally still considered to be reserved for Union soldiers of the Civil War. In 1899, President William McKinley’s Secretary of War Russell Alger, himself a Union veteran of Gettysburg and other battles, formally opened National Cemeteries to meet the demand for new burials associated with the Spanish-American War.

As a new century opened, the role of the Knoxville National Cemetery became almost the opposite of what it had been before. During the Civil War, it was the resting place of men mostly from far away who died in or near East Tennessee and were required by necessity to be buried here. Now it was to be the resting place of men from East Tennessee who died far away–and preferred to be buried here.

The National Cemetery was handsome and much-visited, and became positively attractive to the families of soldiers who had the means to be buried anywhere. For a time, there was little regulation on the installation of private monuments within the cemetery, as long as they were outside of the interior circles. Most of the large monuments date from the Spanish-American War and the subsequent Philippine insurrections, which became much more costly in American lives than the war itself. It was just during that patriotic fervor that the aging Unionists of Knoxville finally succeeded in raising the funds to address the long-nagging lack of a Union monument.

THE MONUMENT

The unexpected war may have delayed progress on the monument. When it was over, beloved journalist and sometime Knoxville Mayor William Rule, now in his 60s, was still chairman of the monument efort. But also helping with the long-delayed project was the committee’s most prominent veteran, Gen. John T. Wilder, leader of the legendary “Lightning Brigade” of Illinois regiments, and most famous for his valor at

Tullahoma and Chickamauga. He had settled in Knoxville as a businessman in 1897, when he accepted a federal appointment here with the McKinley administration. At the time of the monument project, Wilder was the city’s most famous surviving Union-veteran celebrity.

In Rule’s own landmark history of Knoxville, completed in 1900 and still cited by historians today, the project gets a mention as “the incomplete monument standing in this national cemetery.”

Advocates argued about what the monument should depict. Each “camp” of the GAR had its own hero. One proposal was to honor Ed Maynard, a combat veteran who died young–albeit not in the Civil War; he had succumbed to a tropical fever during diplomatic service on Grand Turk Island. (He’s buried at Old Gray under a symbolic broken column.) One leading proposal was to honor a Knox County native, Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, the Union’s greatest naval commander, who was suddenly getting more attention in Knoxville, 30 years after his death, than he ever had before.

Admiral George Dewey himself, then famous as the hero of Manila Bay, visited Knoxville in May, 1900. Here, with much fanfare, and national headlines, he dedicated a small marker at the birthplace of his hero. It seemed to begin a cascade of local accolades for Farragut, who had never previously been honored with the name of a Knoxville-area community, school, or business.

One Frank Seaman, Union veteran and commander of the East Tennessee GAR, was also a romantic poet, and strongly supported the idea of Farragut as the symbol of Tennessee’s Union dead, declaring Farragut the Union’s “Thunderbolt-Stroke.”

What was unveiled on October 24, 1901, was glorious, but different from anything discussed in the 1890s. There was no soldier on top, but, perched upon a large cannonball, a menacing bronze eagle with its wings spread wide.

The year 1901 would have been a signal year for the National Cemetery, anyway, because it was the year of the burial of Medal of Honor laureate Timothy Spillane. A native of County Kerry, Ireland, he was part of the wave of refugees from the Great Famine, and enlisted with the Union army in New York. In the final months of the Civil War around Petersburg, Virginia, at the Battle of Hatcher’s Run, Private Spillane showed extraordinary courage in attacks on the Confederates.

Even after being wounded twice, he refused to leave the field. He lived to receive the commendation in 1880. He died at age 59 on December 3, 1901, not long after the impressive new monument to his comrades had been dedicated.

The bronze-eagle Union monument stood for almost three years, visited by thousands of Tennesseans in the era of vaudeville and the first noisy automobiles. Many rode the electric streetcar to the site.

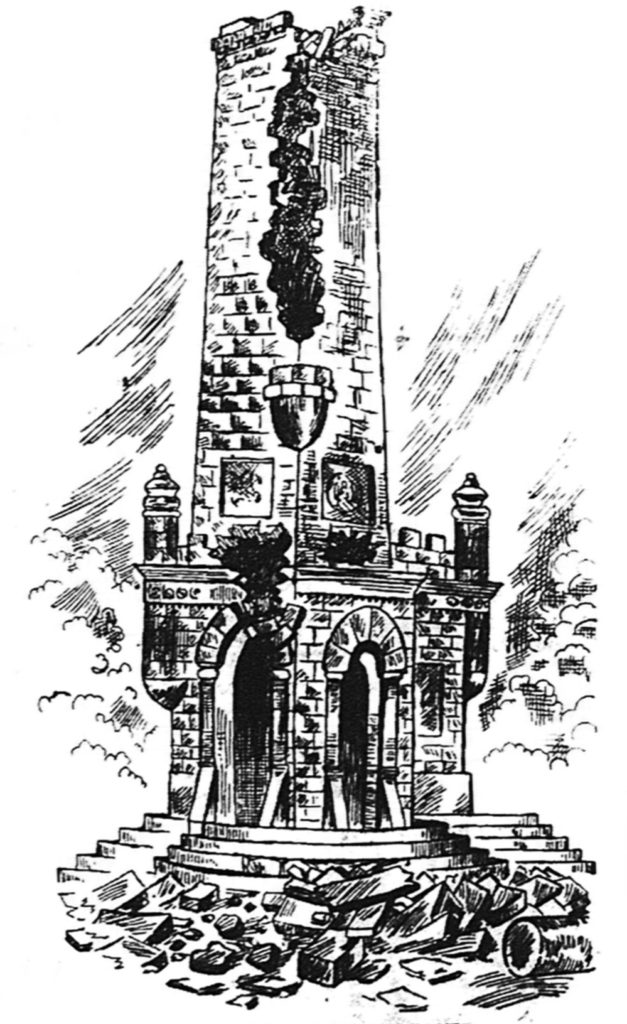

“How the Big Monument Looks”

This hasty drawing appeared in Capt. William Rule’s Knoxville Journal & Tribune only

about 36 hours ater a lightning bolt ruined the three-year-old monument in 1904.

McClung Historical Collection.

On the evening of August 22, 1904, a summer storm rumbled over Knoxville, and a bolt of lightning shocked the city with an explosion that emptied downtown’s saloons. It was so loud that bystanders on Gay Street thought that it had hit the building next door. But the problem was at the National Cemetery, and as word got around, hundreds walked over to see the damage.

The castle-like foundation was a ruin; the blast had sent chunks of marble into the houses that stood across the street. The bronze eagle and its cannonball were missing from the monument’s top. The eagle was found on the ground in four pieces, its head and wings severed, cut apart, remarked one observer, as cleanly as by a surgeon.

Those with engineering minds observed that it had been attached to the foundation with a long steel rod.

The lightning found that rod and blew everything around it apart.

Knoxville may have felt cursed. About one month after the bizarre blast in the National Cemetery, two trains collided on the Southern tracks just to the east of town; the New Market Train Wreck killed about 70, and is remembered as the region’s worst transportation disaster in history. The most famous person killed in the wreck was beloved Rev. Isaac Emory, for whom Emory Park (later place) was then named. One of those injured in the wreck was a Union combat veteran named Henry Gibson, who also happened to be Knoxville’s Republican U.S. Congressman. He recovered in time to sponsor a bill to provide substantial funding for a new Union soldiers’ monument. Gibson then retired to his avocation, epic poetry.

Historians have tried and failed to find more about what prompted the design change, and why it trumped previous proposals depicting human figures. It may have been a compromise to avoid rival loyalties to specific personalities. But one leader of the monument efort, Judge Newton Hacker, hailed it, declaring, “there is no monument in all the broad land that marks a higher degree of patriotism…. May no vandal hands ever mar its beauty.”

Securing the restoration of a Union monument in Knoxville was one of Gibson’s last gestures in a long career in Congress. The government had decidedly declined funding for the monument eight years earlier, but this time the bill passed in April, 1905, the month after he left his seat. The quartermaster general remarked, “It does not appear that the Government has heretofore been called upon to take action in any case similar to the one presented in this bill.” It was perhaps an understatement.

Baumann Brothers, Knoxville’s best-known architectural firm at the time, supervised the reconstruction. As formally completed on October 15, 1906, it had a different design, less dramatic, and very similar to the original plan as revealed in 1896: an eight-foot-tall “soldier of the line,” fashioned of marble, not bronze.

As art scholar Fred Moffatt later remarked, the soldier was unlike his older Confederate counterpart across town–less passionate looking, and more clean-cut, “a somewhat disinterested individual for whom personal honor and prerogatives of race are valued less than military department and obligations of service”–but, significantly, four feet higher.

In its early decades, it was almost always referred to simply as the Soldiers’ Monument, the Union Monument, or occasionally as the Tennessee Monument. However, by the mid-Twentieth Century it was sometimes referred to as the Wilder Monument, in honor of its most famous veteran supporter. (There’s another “Wilder Monument” at the Chickamauga Battlefield, named for the same man. It’s larger than this one, a castellated tower with an interior staircase, but with no statue on top.)

***

National Cemetery was almost 40 years old, around 1902, when the city built Knoxville General Hospital just to its north. The city’s first public hospital, it was Knoxville’s first large permanent medical facility since the Union withdrew from the Asylum Hospital at the end of the war.

Knoxville General was the most prominent feature of the National Cemetery’s immediate neighborhood for half a century. Although it closed in the early 1950s, some aspects of its medical mission, like the county health department, remain in the 21st Century. The nursing home known as Serene Manor occupies what was originally the Negro Wing of the segregated hospital.

One of the cemetery’s larger, non-regulation monuments is the large, granite dedication to Walter M. Fitzgerald. It draws attention not just for its size, but the puzzles suggested by its inscriptions. He died at age 40, but in 1906, not wartime–and in Knoxville, where there was no war outside of midnight saloon fights. Nevertheless, he could be marked as a casualty of war. Fitzgerald had been captain of infantry in Cuba during the Spanish-American War when he came down with malaria, a much-dreaded disease, considered treatable but incurable.

The infected could often manage the disease, though it could remain dangerous for decades. After a battery of experimental treatments, Fitzgerald was his old self for a while. A former printer, he had become a lawyer, and was even elected to County Court, Knox County’s main governing body, and therefore called Squire Fitzgerald. But then, almost eight years after his return, he fell ill again. He died unexpectedly, at his home in the middle of old Irish Town. His doctor called it “apoplexy of the brain,” but considered it a complication of malaria.

Among the pallbearers at his burial at National Cemetery was John P. Murphy, the colorful “Mayor of Irish Town.” National Cemetery’s proximity to the old immigrant community, and Holy Ghost Catholic Church, may have inspired a sense of intimacy with the Irish minority.

In the 20th Century, the National Cemetery became a place of honor more than necessity. Veterans were proud to qualify to be buried there, and even made arrangements to include their spouses, which had not been part of the original plan. That new sense of status couldn’t have been more effectively proven than the fact of one particular burial in 1910. Joseph A. Cooper was a major general.

A Kentucky native who had spent his youth in Tennessee’s Campbell County, Cooper had commanded troops in major battles like Stones River, Chickamauga, and Nashville, as well as Knoxville. He was also a significant Tennessee politician, at the time of the birth of the Republican Party. Disappointed with post-Reconstruction politics in his adoptive state, Cooper moved to Kansas, where he spent his last thirty years.

At the end of his life, Cooper was buried here at Knoxville’s National Cemetery, under a standard Union soldier’s slab in the corner nearest the Union monument. Few officers beyond captain were buried in National Cemetery. Over the years, Cooper’s corner became associated with a small minority of majors and colonels and, much later, one other especially remarkable general.

<<< BACK TO PART II