National Cemetery Part IV

THE GREAT WAR

After about 1906, the National Cemetery had become what it would be forever. From then on, it served to reflect dramatic events in faraway places and, frequently to make room for another worthy soldier’s grave.

World War I drew thousands of recruits from the Knoxville area. About 140 Knoxvillians died in that war, most of them in the fierce fighting of the war’s final weeks, but of course National Cemetery represented a much larger region. A total of 465 soldiers killed in World War I were eventually buried at National Cemetery. Many of the regulation stones bear dates from the terrible autumn of 1918. The non-regulation monuments on the periphery of the original circles honored some of the Great War’s dead. Some of them tell just a bit of a story.

Sergeant Charles McGuire’s stone says, “He lost his life in the World War at Bellicourt, France.” The small, pastoral town was the site of fierce combat during the war, especially in September, 1918, when Americans suffered 13,000 losses in a hard-won fight.

Corporal Ralph E. Boles died in Europe on October 7, 1918, just a few weeks shy of his twenty-fourth birthday. His stone includes a poignant inscription that sounds like last words: “Tell them I did my part.”

One eye-catching World War I-era marker is that of Thomas Ridge. He was a Civil War veteran, but died in the fall of 1918, during the weeks of fiercest fighting and dying in Europe, as if in sympathy. Ridge had been the superintendent of the cemetery for more than 20 years immediately after the Civil War.

He and his wife, Margaret, had made the scarred burial ground a beautiful place to visit. She had died before he did, and he got a special permission to have her buried in the cemetery they had both cared so much for. Although the government didn’t supply Ridge with a comfortable cemetery “lodge” in the early days, their monument is one of the most elaborate in National Cemetery, describing not just his service in the Civil War but his background in County Galway. His obituary praised him as the one who transformed the cemetery from “rugged trenches” to a place of “ornament and beauty” with his careful planting of trees and shrubs.

Much of Knoxville’s memorialization of soldiers killed in wars occurred in the years just after World War I. The first municipal airport was named for Navy flier McGhee Tyson, who went down in the North Sea in October, 1918.

An elaborate Road of Remembrance was established along Kingston Pike, with monuments, and plantings of flowers and trees, but eventually yielded to development pressures, and seems to have disappeared before the next world war. In 1922 the Doughboy statue was erected in front of Knoxville High School, on Fifth Avenue, with Gen. Pershing himself in attendance. In years to come, Decoration Day ceremonies would involve both that statue and nearby National Cemetery, often with participants walking from one to the other.

And many roads were named for war dead, all over town. It was during this time that the roads adjacent to National Cemetery were renamed Cooper, Bernard, and Tyson, after soldiers buried in the vicinity. It had been the war to end all war, and many believed, or hoped, it would be the last, at least the last one to involve Americans in harm’s way. But even enlisting during peacetime can be dangerous.

Seaman First Class Walter Ross Tolson was among the 39 crewmembers lost when a Navy destroyer rammed an S-4 submarine off the coast of Massachusetts in December, 1927. Perhaps the horror of picturing the final minutes of a sailor in a sinking submarine inspired a peacetime community to offer him extraordinary honors. Tolson was buried at National Cemetery with honors rarely known to heroic combatants: a parade from downtown, and at the cemetery, an airplane circling overhead, strewing memorial flowers.

MEMORIAL DAY

What had been known as Decoration Day after the Civil War was more often called Memorial Day by the 1920s, and it was the most popular time to visit the National Cemetery.

The May 30 ceremony was often different year to year, but often involved a multi-station parade, typically originating at the Gay Street Bridge, with a morning memorial to the victims of the Sultana disaster, always involving tossing a wreath, or an anchor-shaped arrangement, or just baskets of flowers, into the river.

Then came a stop at the Knox County Courthouse, and sometimes a speech and a wreath at the feet of the large Spanish-American War statue on the front lawn. Then a parade down Gay Street, all the way to the Doughboy Statue in front of Knoxville High School. There, often, a Gold Star Mother of the World War would lay a wreath, and there might be more recitations of poetry or a short speech. Then the pageant would move to the nearby National Cemetery, and that was typically the main event, a lengthy but diverse ceremony that included a brass band playing the National Anthem; sometimes a choral group singing a patriotic song like “America”; a local celebrity reading of Gen. Logan’s Order No. 11, which established Memorial Day as a time to visit and decorate graves of fallen soldiers; a prayer by a prominent local minister; a reading of the Gettysburg Address; an address, sometimes a lengthy one, by a prominent citizen, sometimes a visiting dignitary, typically a congressman, judge, educator, or notable veteran; multiple volleys fired by an honor guard; and a bugler finishing the ceremony with “Taps.”

The Gettysburg Address recitation, typically by a guest speaker different from the others, seems to have been a constant. Lincoln delivered the address to dedicate a cemetery in Pennsylvania while Knoxville was under siege. In fact, the Union’s most famous casualty of that conflict, Gen. William P. Sanders, died in downtown Knoxville on Nov. 19, 1863, the same day Lincoln gave his most famous speech.

The coincidence of that address with Knoxville’s most dramatic experience with the war may have given it special resonance. The full text of the Gettysburg Address is permanent presence at Knoxville’s National Cemetery today, embossed in steel in the cemetery’s northeastern corner.

Patriotic Display, National Cemetery, 1921

Thompson Photograph Collection, McClung Historical Collection.

Although Laura Richardson’s innovation of sixty years earlier was sometimes mentioned as a “tradition,” most specific descriptions of Decoration Day ceremonies mention flowers, though flags were at least occasionally used to adorn individual graves at National Cemetery. That was the case in 1922, when 4,000 flags were distributed for planting with each white slab.

On Memorial Day, 1928, the cemetery was to receive one last visit from an old friend. It was the era of radio and sound movies, but Capt. William Rule, Union veteran, indefatigable champion of the cemetery’s monument, was still the editor of the daily Knoxville Journal, and an influential figure in town. The old man with a dapper white beard was slated to introduce Spanish-American War veteran W.T. Kennerly, the day’s speaker.

But illness, rare in the old captain’s life, prevented his appearing that day. Rule died later that year, and was buried in the family plot at Old Gray. The Union veterans of the dwindling Grand Army of the Republic were still gathering at National Cemetery as late as the 1933, bringing armloads of flowers, often alongside members of the Spanish American War Veterans and the American Legion.

In 1930, the holiday’s official master of ceremonies was an extraordinary celebrity: Pleasant M. Keeble, the last local survivor of the Sultana explosion. He began the day strewing roses in the river from the Gay Street Bridge, remarking that the sight of them floating reminded him of the heads of his comrades floating in the Mississippi, 65 years before. Later, at the National Cemetery, he served as the host of a long program. He died the following year.

Promoted by George Bergrantz, a Navy veteran of Dewey’s command at Manila Bay in 1898, the wreath-dropping tradition prevailed for many years. As references to the Sultana faded, it became a more generic gesture for the Navy and the Marines, and lasted into the 1970s.

The Grand Army of the Republic remained an official participant in Memorial Day ceremonies for fully 75 years after the Civil War. The final Union veteran to attend ceremonies was apparently Private Francis M. Underwood, who attended in 1940, proud that he had, as a teenager, been part of Sherman’s March to the Sea. He died about a year later at age 93.

By the time of World War II, Knoxville was home to only one known Union veteran: former “drummer boy” Martin Parmelee, who loved Memorial Day, and usually celebrated it in his neighborhood, within walking distance of National Cemetery, by banging his old drum.

ANOTHER WORLD WAR

Veneration for the National Cemetery continued each Memorial Day without a break, even, or especially, as America entered a major war. Notable educator Burgin Dossett, longtime president of East Tennessee State University, gave the first wartime address at National Cemetery in 1942. Offering the cemetery address in 1945 was James P. Pope, former mayor of Boise and former U.S. senator from Idaho; he was in Knoxville because he was, at the time, director of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Considering that all combat casualties of World War II were sustained overseas, thousands of miles away, many of the burials from that war took place several years after the battles. Second Lt. Lawrence Anderson, for example, was a bombardier in a B-17 when his ship was shot down during the Normandy invasion. He was buried at Knoxville National Cemetery four and a half years later.

During the postwar period, the National Cemetery’s location, near a central point in the most populous half of the nation, sometimes played an interesting role. Often, the dead came home not in individual coffins, but mingled with their comrades after a plane crash or bomb blast. In such cases, the Army’s policy was not to try to separate the remains and find the home towns of each, but to locate a central point accessible—within a day’s drive, perhaps–of all of their families. When three soldiers from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New Orleans were buried together, the Knoxville cemetery seemed a natural choice–though it’s possible that none of the soldiers had ever been here before.

In 1951, parents of a Lt. Jacob Rosenberg, killed in a Flying Fortress crash in Austria in 1944 and buried with four fellow crewmen, drove all the way from Tampa to attend a Memorial Day ceremony for their son, buried in a common grave in a place considered centrally located for the crew’s far-flung families.

Some of these group burials, a couple of them obviously from bomber crashes, are in the southeastern part of the cemetery, near the Soldiers Monument, and among the higher-ranking officers in the cemetery.

Among the thousands buried here are some who stand out, none more than U.S. Army Sergeant Troy A. McGill. The Knoxville native was living in Oklahoma when he joined the army in 1940, before the United States was part of the war. He was defending a position against a fierce Japanese attack in the Admiralty Islands of New Guinea when he found himself the only man left. He kept fighting, and as his

rifle quit working, he died in hand-to-hand combat on March 4, 1944. He was 29 years old at the time.

He earned the Army’s highest commendation, the Medal of Honor. Originally kept in a military mausoleum in the Philippines, his remains were reinterred here in 1951.

The first black soldier lost in combat in World War II was First Lieutenant Edward Cothran, a standout scholar at Knoxville College, was missing in action in Italy in October, 1944. His body, eventually recovered, was buried at National Cemetery four years later.

Rev. Lorenzo Alexander, black pastor of Rogers Memorial Baptist Church, trained at Harvard University to be an Army chaplain, and enlisted. With the rank of captain, Alexander served in the Pacific theater. Soon after the war, he ran unsuccessful for Knoxville School Board, the first black in memory to make that attempt. He died at age 53 in 1960, and was buried at National Cemetery.

After that war, for whatever reason, poppies—associated with World War I, and more specifically with the British experience–became a regular feature each Memorial Day, along with the little flags.

Meanwhile, as National Cemetery was still accepting delayed burials from battlefields of World War II, another, newer war began sending its own dead to the cemetery on Tyson Street. Private First Class Bobby Riggs was just 18 when he died of wounds in early September, 1950, making him one of the first Knoxvillians to die in the Korean War. He was buried at National Cemetery, with many of his comrades.

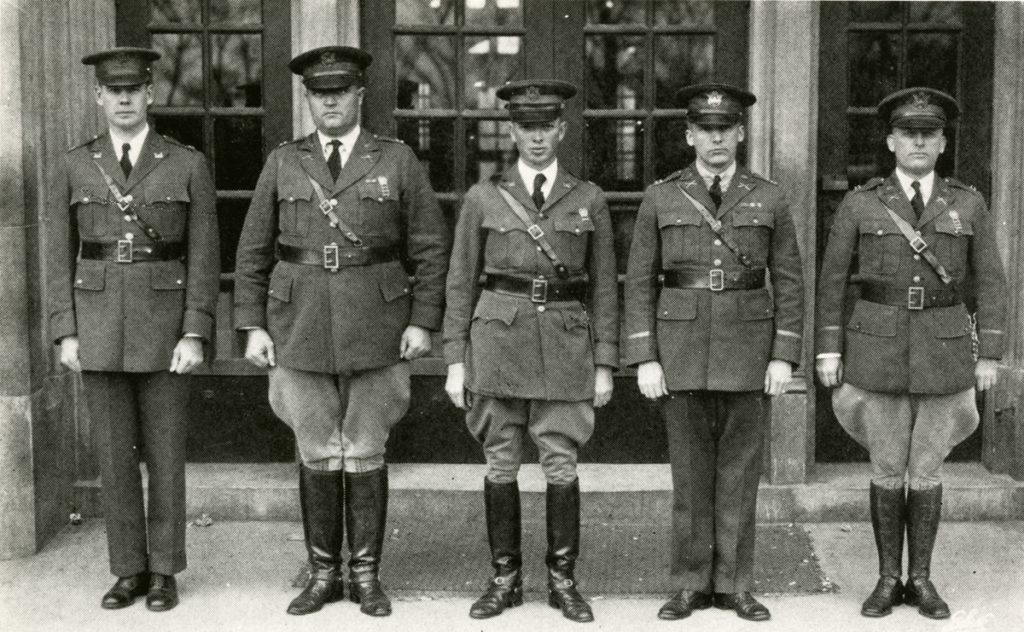

1929 UT Military Department Staf with Major Robert R. Neyland (far left),

ROTC commandant, 1928-1930.

Volunteer Moments: Vignettes of the History of the University of Tennessee, 1794-1994.

The single best-attended burial in National Cemetery history may have been that of the cemetery’s second highest-ranking honoree, a veteran of both world wars. However, he was most famous for a different form of combat. Brig. Gen. Robert Neyland was the West Point-trained football coach who brought the Tennessee Vols to national prominence in the 1920s and ’30s. He became the honoree of the name of one of America’s largest football stadiums.

Neyland was retired when he died unexpectedly in March, 1962. After spending his life in the military, the Texas native wanted a simple soldier’s burial, with “the least commotion possible.” There was no military pomp and circumstance, just a hearse from a nearby mortuary and a flag-draped casket. Hundreds witnessed the burial, including Governor Buford Ellington, university president Andy Holt, and Vol coach Bowden Wyatt.

Gen. Neyland was buried with a simple stone like the others, between a captain and a colonel.

STREET NAMES

During the early decades of the National Cemetery, all the streets that touch the National Cemetery plot had different names. Tyson Street, later renamed for a notable combat veteran and his family, was Holston, sometimes spelled “Holstein.” Bernard was Munson. And Cooper Street was Jacksboro Pike. (As hard as it may be to believe today, Cooper Street, which forms the cemetery’s western boundary and gets very little traffic, was once a thoroughfare to Campbell County, on the Kentucky border–and its county seat, Jacksboro.)

All three of the modern names are those of U.S. military veterans.

Cooper Street was renamed in the early 20th century for Hobart Cooper, according to newspaper columnist Bob Cunningham, who also claimed it was named for Gen. Joseph Cooper. Either way, it was a Union veteran involved in the defense of Knoxville.

Tyson Street is named for Brig. Gen. Lawrence Davis Tyson and his son, McGhee, for whom the Knoxville airport is also named. Members of one of Knoxville’s wealthiest families, they are not buried at the National Cemetery, but at Old Gray, within clear view of Tyson Street.

Bernard Avenue, which is several blocks long, was named for Lt. Jack Bernard, a University of Tennessee alumnus killed in a charge on the Spanish blockhouse at El Caney in Cuba in 1898. He’s buried in the National Cemetery.

BIVOUAC OF THE DEAD

A marker quotes several lines from Theodore O’Hara’s “Bivouac of the Dead.” Honoring that particular poem might seem surprising, considering that the Kentucky-born poet was a Confederate colonel who had seen combat against U.S. forces in Tennessee campaigns. However, O’Hara had written the poem, already beloved before the Civil War, about U.S. casualties in the Mexican War of the 1840s. Parts of the poem appear in both Union and Confederate cemeteries.

The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat

The soldier’s last tattoo;

No more on life’s parade shall meet

That brave and fallen few.

On Fame’s eternal camping-ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards, with solemn round,

The bivouac of the dead.

PERPETUITY

Enemies change, wars change, but some things are perpetual. On Memorial Day, 1965, 500 Cub Scouts descended on the National Cemetery to plant a flag on each of 7,184 soldiers’ graves.

The Vietnam War brought more war dead, some of them teenagers, like Private Wayne T. Long, killed in action two days after Christmas, 1965, less than three weeks after his 18th birthday. He rated an honor guard in the cemetery and a 21-gun salute.

The ten-acre spot designated, a century before, only for Union war dead in the American Civil War made room for soldiers who died in another country’s civil war. By then, the nearby neighborhood was getting run down. The Knoxville General Hospital had closed years before, and the streetcar neighborhoods that had attracted young Civil War veterans in the 19th century were no longer as appealing to families in the era of the Interstate. Business was drying up, and nearby North Central had become a magnet for crime.

Even adjacent Old Gray, once the city’s garden spot, had become run down, rarely visited, often vandalized. New interest ushered in improvements at the older cemetery in the late 20th century. Today, Old Gray and National Cemetery form an almost perfect contrast: Two styles of cemeteries, both introduced in the mid-19th century, yet nearly opposite. Old Gray is gothic, shady, wild, with several slopes and large and small trees and shrubs, stones large and small, with statues, mostly of young women, some of them broken or missing. National Cemetery is bright and orderly, its curvilinear rows nearly perfect, its stones numbered and easy to find. And it seems, even after more than 150 years, perfectly intact.

Old Gray uses gray and pink Tennessee marble, with an occasional outlier, a wealthy family’s stone imported from Michelangelo’s favorite Carrera quarry in Italy. National Cemetery uses white Vermont marble.

In a new century, Old Gray’s huge trees, meandering lanes, steep slopes, and weathered Victorian statuary offer a sharp contrast to the more perfect order of the National Cemetery.

Today’s familiar historic neighborhoods like Old North and Fourth and Gill, both within easy walking distance of National Cemetery, did not even exist when Burnside’s men first laid out this cemetery with its concentric-circle design. The oldest graves in National Cemetery are older than the oldest houses in this north-side district.

The whole neighborhood seemed to be improving in the 21st century, when new wars claimed more American lives. National Cemetery has not changed. It is the one constant in the neighborhood, through its ups and downs, welcoming large factories, then closing them, building Victorian houses, then watching them rot, then restoring them. Through it all, National Cemetery maintained the basic appearance of order, reverent quietude, and respect for the “departed brave” that Gen. Dewey cited when it was a cemetery for Union soldiers during the Civil War.

National Cemetery has shifted its purpose, to some extent, originally an emergency burial ground for Union soldiers who died in combat in East Tennessee, most of them from hundreds of miles away, many of them unknown–it transformed seamlessly into a place of honor, a cemetery mostly for East Tennesseans who fought in wars thousands of miles away, but came back here because they or their families preferred it. Some died in combat as young men, some died as aged veterans. But they all came here with the aid of their comrades and families, more than 9,000 of them now, to be buried, and, with the help of the devoted living, to be remembered.

###

This project was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Legacy Program through the University of Tennessee.