Alfred E. Anderson’s unique career in civil rights was versatile, inspiring, and ultimately tragic.

This is an incomplete story. Like many Black men of his era, there’s much about Alfred Anderson we don’t know, like where he came from or what, exactly, caused his tragically early death. But in Knoxville over a period of 15 years or so, he was something like an icon, from ice-cream maker to teacher to family man to charismatic pastor to provocative avatar of civil rights, to possible murder victim.

***

Rarely, outside of major revolutions, does a society change as much as Knoxville did between 1855 and 1870, the era before, during, and after our deadliest war.

The 1850s were dark times when the thunderclouds of hatred and dread were just part of the daily atmosphere. No one was willing to admit they were wrong about slavery, foreigners, or anything else. They did what people do, when criticized in public. They dig in, double down, ramp up, lash out. It appeared something terrible was likely to happen, as of course it did.

But there were moments of sunshine. Lots of things were looking up in Knoxville’s summer of 1855. After about 25 years of efforts, of building bridges and blasting through mountains and overcoming setbacks due to recklessness and fraud, Knoxville was finally getting railroads. The line from Dalton, Ga., with 20 stops along the way, connected the city to the Southern seaboard and indirectly to the rest of the nation.

As the Knoxville Register put it, “we vividly realized that a new era for Knoxville had arrived.”

As if to celebrate that news, an ice-cream maker with a small shop on Main Street, delivered bowls of freshly made ice cream to the newsrooms.

Alfred E. Anderson was a “free person of color.” A Black man unable to vote by the 1834 Tennessee Constitution, not trusted on a jury, not considered the white man’s equal, he was nonetheless free to open a business, make people happy on a summer day, maybe make some money.

Ice cream was hard to make. A few affluent people took the trouble to make it for special occasions, like a garden party, but it usually worked only if they had servants to do the churning for them. Also, you needed ice, and to get that you needed access to an ice house, an insulated place usually dug into the ground where ice from the winter sometimes lasted for several months. There weren’t many of them. Ice was rarely available at all, and when it was, as late as June, it went for the equivalent of $40 a bushel.

Machinery developed in the 1840s made ice cream a little easier to make, but the process was still labor intensive. Only a few people had taken the initiative and hard work to try to make enough ice cream to sell on the street on a daily basis. It’s interesting that one of the very first, a few years earlier, was a free Black man remembered only as “Losson.” But one of the best known, of that first generation of ice-cream makers, was young Mr. Anderson.

The fact that it was the week just after the first railroad train arrived in Knoxville was probably just a coincidence. That first trains came up from Georgia early that summer; it seems unlikely they were carrying ice. But trains were opening up all sorts of possibilities for the half-forgotten old town. It was in some ways a horrible time to be here, but in that one decade, the city tripled in population.

Wherever he got his ice, Anderson may not have had the money to advertise directly. What he did was take a bowl of fresh ice cream to both the competing newspapers, the Register and the Standard.

In 1855, even as they had political reasons to despise each other, all three of Knoxville’s rival weekly newspapers were panicking about the specter of Abolitionism. But they were also resentful of the Southern so-called aristocracy, and the prospect of secession. And worried about immigration, which had been coming in waves, and different from earlier eras of immigration; many of these newcomers didn’t even speak English.

On June 28, 1855, the Knoxville Standard, the Democratic Party weekly, hailed something new that seemed significant, and a refreshing break from the awkward, twisty politics of the era.

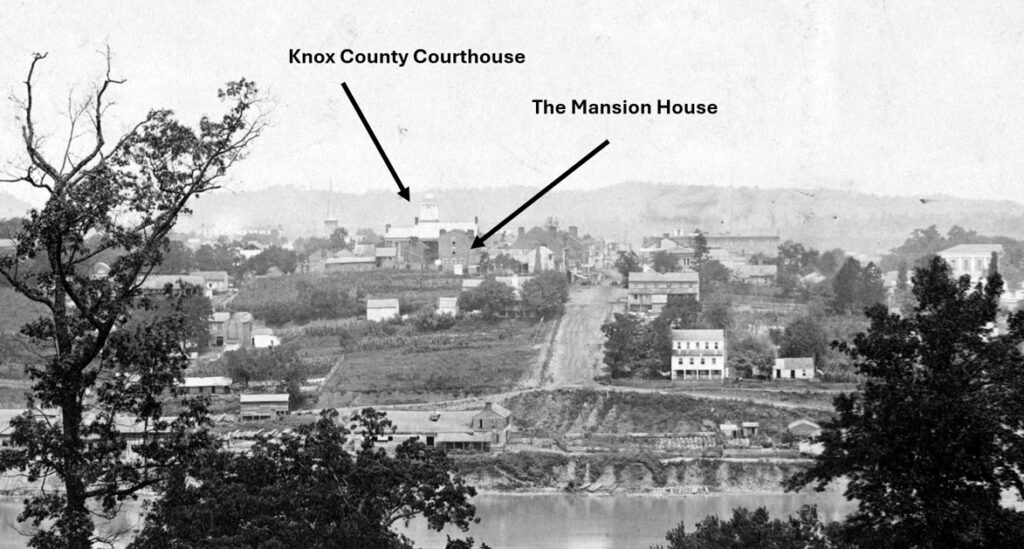

“We received yesterday, from Alfred Anderson, a large bowl of ice cream with the necessary amount of cake, which was duly discussed by all hands, and pronounced the best of the season. His establishment is three doors west of the Mansion House, where he is prepared to fill orders for parties or private families at short notice and on reasonable terms. We would recommend Alfred’s establishment to the young gentlemen, during the hot weather, as ice cream is much better than a glass of brandy or a mint julep and costs no more, without the evil consequences of the latter.”

The Mansion House was a hotel that stood near the site of what later became the Knox County Courthouse, so Anderson’s place was likely in the vicinity of what’s now the entrance to the City County Building. The confusion of the era may be notable in the fact that the same issue of the Standard promoted Andrew Johnson, who would be a defiant Unionist in 1861, for governor of Tennessee—while on the same front page also advocating D.H. Cummings, who would later be a Confederate colonel who led men into battle at Shiloh, for U.S. Congress.

Meanwhile, down the street, the Register was Knoxville’s oldest paper, not always politically predictable but at the time friendly with the anti-immigrant American Party, and supporting former Whig Congressman Meredith Poindexter Gentry, of Middle Tennessee, for governor, against Johnson. Gentry would later be elected to Confederate Congress. But John Fleming, the Register’s editor who was probably behind that endorsement, would soon become one of Knoxville’s hardcore Unionists.

Without prejudice, Anderson shared his ice cream with the Register’s staff, too.

“Alfred Anderson (colored) has a superior article of Ice Cream,” opined the Register on June 28, “served up daily, and sent to any part of the city, when ordered. He [Anderson] desires the lovers of a good article to come to his Saloon, Main St., below the Mansion House, or send in their orders.”

In the summer of 1855, ice cream was the universal language. On a summer day you might almost believe it could forestall the deadliest war in American history.

We don’t know what flavor it was. Perhaps Knoxvillians of 1855 weren’t sufficiently accustomed to ice cream to recognize flavors. We can only hope the sacrifice was good for Anderson’s business. It is, at least, flattering to his historical reputation as one of Knoxville’s first masters of ice cream.

He seems to drop out of sight for a time; he’s not obviously listed in the first-ever City Directory of 1859. But the only people included were those who lived in the old part of town.

We don’t know much about Anderson’s fortunes during the war, except that he lost a child. He was married to a woman named Mary, and they had at least two children. Their toddler son, Ambrose Burnside Anderson, was named for the Union general who had recently occupied Knoxville. But before reaching the age of 2, he died of whooping cough.

In their Fourth of July, 1864, issue, the Army Mail Bag, a Union soldiers’ newspaper, ran a little poetic eulogy for Anderson’s son. It went, in part:

“Rest, sweet one, rest! Thy brief life done

Thou art forever blessed.”

Perhaps the war or personal trauma led Anderson to seek ordination in the Methodist church. By 1865, he was known both as a pastor of the growing A.M.E. Zion movement, founding pastor of what became famous as Logan Temple, and as an educator, superintendent of the Freedman’s School.

Sponsored by the Free School League of East Tennessee, it was intended to replace an earlier disappointing effort by the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission, which had recently pulled up stakes and left town without paying the teachers who had worked for it. Anderson’s school enlisted Rachel Alexander, a Black woman who had attended Oberlin College in Ohio—America’s first college to admit both men and women, regardless of gender or race—and New Yorker Charles Brooks, who became principal. It taught students who had recently lived in slavery, and taught teachers to teach more of them.

Historians have found a rare personal remark from Anderson, that he “sacrificed my business” to teach. “I felt that these people must be trained, for I know they were human.”

***

They didn’t call it Reconstruction here. Among states formerly allied with the defeated Confederacy, Tennessee, the first state to rejoin the Union, was unique in its relative autonomy. Resident Unionists, now mostly called Republicans, were in charge of the state government. And as it happened, the president of the United States for most of that period was a Tennessean. But that Tennessean, although as bold a Unionist as anyone, was despised by the new Republicans of Tennessee. Allies a couple of years earlier, they had different ideals about the postwar state, and about the roles of emancipated Black people versus those of former Confederates. Knoxville was a seething cauldron of opposites, a melting pot maybe but not nearly hot enough to melt everybody.

Some were defeated Confederates, many of them still convinced their cause was just, that they were defending their homes, that their enemies were self-righteously arrogant. Some were Republicans who regarded themselves as patriotic, moral, and victorious. Some were gamblers, playing one side or the other, as the tides turned. Several survived the war missing a limb or two, or one or both eyes. Whatever happened next, it was going to be different from anything they had known.

Complicating the picture even further was that, more than ever before or since, due to dangerous civil disruptions in Europe in the years before America’s Civil War, Knoxville was also populated with immigrants, refugees with foreign accents who having already survived other traumas from violence to oppression to starvation were still trying to get their bearings in a confusing new country. Some immigrants, typically in their first decade in America, had found reason to side with either the Union or the Confederacy, but many were still idealistic about the icons of their homelands, Garibaldi and Bismarck and O’Mahony.

And then there were the people with dark skin, some of whom had already been free before the war, more of whom had been recently emancipated from being owned by other mortals. In Tennessee, unlike most states in the Union in 1867, Black men were voting for the first time, wondering how far they can push this idea of equality.

Left out of the political sphere altogether, women of either European or African ancestry couldn’t vote at all, and most would not live to see the day they could. But they were here, and some found interesting ways to join the conversation.

To a degree that town fathers might not have expected, Black voters, whether they’d been enslaved or free before the war, made their voices known right away.

Their leaders were a mixture of longtime locals and newcomers. Among the locals were attorney William Yardley, publisher William Scott, and suddenly businessman-turned-cleric Alfred Anderson.

Dr. J.B. Young was a newcomer. Remembered as one of Knoxville’s first Black doctors, his origins are hard to nail down, but he was by some secondhand accounts a graduate of Cambridge University in England. In any case, he cut a dashing figure in postwar Knoxville, one day to be described in Northern newspapers as “a shining light of radicalism in Tennessee.”

He set up his medical practice right on Market Square, and rose to the public fore in February 1867, at a “Meeting of Colored Men” organized and hosted by Rev. Alfred Anderson at his Logan Temple church, downtown at Marble Alley. Dr. Young was one of five framers of a series of resolutions affirming loyalty to the Radical Republican Party supporting the principles of Reconstruction, especially the right to vote, which was not yet guaranteed. In particular they pledged their support for “Parson” W.G. Brownlow, who was then governor of the state, who had found himself, perhaps to his own surprise at age 62, one of the fiercest civil-rights politicians in the nation. Among the hundreds of Black men who attended, a cheer went up when they called for Brownlow’s re-election.

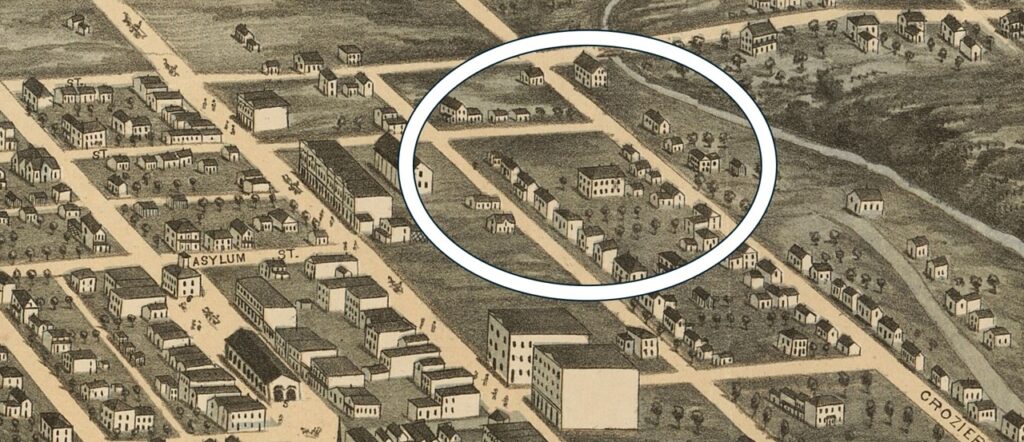

Knoxville map, 1871 (detail.) This area, near what’s now Marble Alley Lofts, was Rev. Anderson’s neighborhood—he and his family lived on Water Street until 1870, about the time of this depiction—and that of his nearby church, Logan Temple A.M.E. Zion, founded just after the Civil War. It may be the large building in the middle. (Library of Congress.)

All those people, not necessarily reconciled, not necessarily friends, made up a fascinating era that despite some war-related violence including a couple of fatal gunfights, seems something like a municipal Renaissance. Black voting equality was new, but so were baseball, opera, beer, passenger train travel, Christmas trees, and all-night dances. Hardly anyone was the same person after the war as they had been before.

***

Anderson became one of Knoxville’s busiest preachers, delivering multiple sermons every week to a congregation of 200 at Marble Alley. In the late 1860s, Rev. Anderson and his wife Mary and little daughter Kattie lived very near their church, on Water Street, now South Central, somewhere north of Union Avenue.

Strongly opinionated, Anderson aligned himself with the radical pro-civil-rights faction, but finding some distance between himself and some of his allies, especially righteous interlopers from out of town. It was a chaotically complicated era of shifting alliances, of arguments both political and personal.

Anderson impressed people of all races with his speeches and sermons. The Knoxville Weekly Whig was Gov. Brownlow’s paper. Like most papers of the era, the Whig made plenty of room for paradox and irony.

The Knoxville Weekly Whig of Feb. 13, 1867, made a surprising recommendation of a former ice-cream man to its ostensible enemies:

“It is the declaration of some of the leaders of the Conservative Party of Knoxville that they will vote for Alfred E. Anderson of this city for the office of Governor. Mr. Anderson is a colored man and a thorough Radical, and is as sure to be relied on in voting against rebels and their sympathizers as Thad Stephens or Charles Sumner. [Thaddeus Stephens and Charles Sumner were two of the Northern congressmen most punitive toward the former Confederacy.] The use of [Anderson’s] name in connection with the Conservative nomination is entirely unauthorized. He is a finely educated man, and a popular orator of rare ability. As a minister of the M.E. Church, he is in good standing. That Conservative leaders of Knoxville should desire to vote for him for Governor we regard as evidence of the improvement of their morals and a returning love of country.”

Parson Brownlow may have had a soft spot for fellow Methodists. But rhetorically, at least, Brownlow’s Whig claimed that as a potential statesman, Anderson was superior to the white Tennessean who was then president of the United States:

“The majority of the leaders of this Conservative party voted for Andy Johnson for Governor. No loyal Tennessean who has pride of character would not feel that Anderson would be a vast improvement on Andy Johnson.

“Anderson has more ability. Anderson is a man of personal integrity, Johnson is not…. If elected Governor, Anderson would not get drunk and deliver his Inaugural Address in a state of beastly intoxication ….” The reference, of course, was to the fact that Johnson was drunk when took the oath of office as president in 1865.

“The Radicals will run a white man for Governor, and with the aid of 40,000 black men like Alfred Anderson, and eight regiments of loyal militia to enforce the laws, will certainly elect him….”

Brownlow went a little farther to rub dirt in the face of his opponents, suggesting a Black man would be a greater president than Johnson: “The occupancy by Fred. Douglass of the Presidential chair would go far to redeem that exalted station from the opprobrium attending to it through Andrew Johnson’s disgraceful and treasonable conduct.”

***

In June 1867, a Republican Union Committee appointed Anderson to represent the Congressional Second District in a committee of “colored Unionists.”

Later that year, the former ice-cream man became one of 30 Republicans appointed to represent Tennessee’s Second District at a Republican convention in Baltimore. Joining him were a biracial mix of several major figures of the present and future of Tennessee history: Wm. Scott, John Bell Brownlow Leonidas C. Houk, Joseph A. Cooper, William Rule, Mayor Marcus DeLafayette Bearden, Rev. George W. LeVere—and Dr. J.B. Young.

***

On April 30, 1868, the Knoxville Press & Herald seemed to be making some speculative nominations about the upcoming congressional election, considering a proposal that one Tennessee seat should be reserved for a Black representative, a proposal that a Nashville newspaper declared was being undermined by ostensibly progressive whites, including Knoxville’s Union veteran Gen. Joseph Cooper, who sometimes served on Republican committees with Anderson.

“If Nelson Walker or Alfred Anderson or any other colored man of that class would announce his name, his election would be a certainty.”

(Nelson Walker was a Nashville figure: born into slavery, he eventually became a successful businessman and bank president. The prospect of a Black man in U.S. Congress turned out to be speculative. Although Tennessee was progressive in many ways, especially in the five years after the Civil War, the state would not elect a Black person to Congress until Harold Ford in 1975.)

Unlike cities in much of the South, resisting old patriotic U.S. holidays, the Fourth of July, 1868, was a very big deal in Knoxville, where celebrations included a procession of firemen, a balloon ascension, and fireworks, despite the heat (“the torrid terrors of the day in no wise suffocated their patriotism,” claimed one reporter). “The colored population had a celebration of their own which was orderly conducted,” reported the Press & Herald. “Their orator was Rev. Alfred Anderson who, we understand, gave a very sensible speech.”

Among the other speakers at that outdoor event, in a lovely sounding grove called Mulberry Spring, were other Black leaders significant in Anderson’s short career: Rev. George W. Le Vere and Dr. J.B. Young. Planning for the event had taken place at Dr. Young’s office on Market Square.

***

Often demonstrations led by Rev. Anderson, Dr. Young, and others were specifically political.

“The negroes held a large and enthusiastic meeting at Alfred Anderson’s church last night”—that was Monday, May 31, 1869—”in the interest of Stokes for governor. They were addressed by Dr. Young, who explained the frauds and inequities of the Convention, and told them Stokes is their friend.”

Willliam B. Stokes, a Republican U.S. Congressman from Middle Tennessee, was a former slaveowner who had nonetheless served as a Union officer, and became a pro-civil-rights politician after the war. He never got to prove that he was the Black voter’s friend. Stokes’ try for the office of governor was unsuccessful, and in fact the following year he lost his congressional seat in the rising tide of Confederate-friendly politics, whereafter he vanished from the headlines.

***

Anderson became known well beyond Knoxville. At a picnic in Maryville that July, “Rev. Alfred Anderson was the principal orator of the day, and spoke at considerable length on the advancement of the colored race,” reported the Daily Press & Herald. “The train returned at 6:00 in the evening with the party, who were cheering and waving their handkerchiefs, from which we infer that they had a lively and pleasant time.”

In October of 1869, Anderson was a planner of a “camp meeting,” a week-long Revival at Fountain Head, sponsored by AME Zion. The area along the creek, not yet called Fountain City, was a popular gathering place for evangelists of both races.

“Great interest has been awakened amongst the Negroes, and eloquent sermons have been preached by Rev. Alfred Anderson,” reported the , adding that the rural neighbors had no trouble with the gathering.

When a Rev. F. Schade, a character distrusted by some, preached there, on the same day as Anderson, he was unsettling to the former ice-cream man, who took Schade for an operator.

When Schade requested an opportunity to preach at a conference of Black Methodists in Chattanooga, according to the Press & Herald, “Alfred Anderson informed him his services were neither needed nor desired at the conference, or in the pulpit of Zion church, which he had so long desecrated.”

There’s probably more to that story. Schade remained welcome at some Black churches.

***

In December, 1869, Rev. Anderson, Rev. George W. LeVere, Rev. John Dogan, and City Councilman Isaac Gammon—one of Knoxville’s first two Black elected officials—made a public appeal, signed by 18 other Black community leaders, to attorney John Baxter to address them in public at the courthouse to address their questions about the upcoming state constitutional convention, at which Baxter would represent Knox County. Its main purpose was to rewrite the antebellum constitution to reflect the latest changes in the U.S. Constitution, especially those concerning the permanent banning of slavery. Slavery had been illegal in Tennessee since 1864, but it seemed urgent that the new constitution carve that in stone.

Baxter agreed to speak to the group.

Baxter, a former slaveholder who had changed sides twice during the Civil War—he had both run unsuccessfully for Confederate Congress and as a lawyer defended the Unionist bridge-burners, the guerrilla saboteurs who had wreaked havoc during Confederate occupation. After the war, he had expressed opposition to allowing Black men the vote.

Baxter was a figure of some anxiety to the civil-rights community. At the courthouse on the evening of Friday, Dec. 10, Baxter gave a speech he’d given to a mixed race but mostly white crowd the night before. He had experienced a change of heart, he said, and now favored an amendment to the U.S. Constitution “to forever place the ballot in the hands of the colored people.” He added, “Experience has proved that it is unsafe to exclude even a small minority and give power to one class alone, because it breeds a spirit of hostility.”

According to the Press & Herald, “About 300 colored men attended and listened attentively to the speech.” There’s no obvious record of how they responded.

That call for Baxter to account for himself may have been the last time Rev. Alfred Anderson, this man once touted as a prominent statesman was directly involved in public politics in Knoxville.

***

Learning what happened next may require some reading between the lines. By the end of the decade, Anderson’s fortunes seem to be fraying a little around the edges. At a public political meeting at his own church in 1869, Presbyterian Rev. LeVere presided over a public meeting inviting political candidates, mostly white, to speak to Black voters. Marcus DeLafayette Bearden was there, and a popular figure with the crowd, as was Union Maj. Eldad Cicero Camp, who the previous year had shot and killed a former Confederate officer, Col. Henry Ashby, to death in the street in a gunfight sparked by an argument about the war.

A motion to invite Rev. Anderson to speak “to explain the object of the meeting” was voted down, without recorded explanation.

He had developed some friction with some of his colleagues and erstwhile allies, especially the prominent and much-admired Dr. J.B. Young.

Young was joined a small delegation of Tennessee Republicans on an unusual junket to Washington, D.C., to meet President Grant and congressional leaders. Other members of the committee were the aforementioned Maj. E.C. Camp; and Horace Maynard, the city’s first Republican congressman, soon to be Grant’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Also along was Third District Congressman and former gubernatorial candidate Wm. B. Stokes. The delegation was in Washington to lobby for better protection for Black voters in Tennessee. They reported that Tennessee’s former Confederates, specifically the Ku Klux Klan, were terrifying Tennessee’s progressives and undermining the newly earned civil rights. They called for federal troops to return to Tennessee to ensure safety, especially with the approach of the Fifteenth Amendment. By then, Black men in Tennessee had been voting for almost three years, but some Tennessee whites opposed the new Constitutional amendment guaranteeing it forever. Young and his delegation feared there would be violence and intimidation.

It was a controversial meeting back home, celebrated by many Republicans, but shocking to those who claimed their fears were exaggerated, and that their visit undermined the state’s image. The Daily Press & Herald reported it under the headline, “Tennessee Slandered.”

By some accounts, it was during that visit that something troubling of a more personal nature came to light. Young and Anderson had been allies who worked together for at least three years. But while Young was in Washington, that friendship came apart dramatically.

In Knoxville, Anderson had accused Dr. J.B. Young of “being guilty of all the sins in the decalogue, especially the seventh.”

In other words, if you count the Ten Commandments, Anderson accused Young of adultery.

That month, Anderson soon sued his wife, Mary, for divorce and left Knoxville, reportedly making a declaration that he was surrendering his wife to Dr. Young. One story holds that Anderson’s letter arrived and was delivered to Dr. Young in Washington, just as he was meeting with key Congressman Benjamin Butler.

The Baltimore Conference of the A.M.E. Zion Church reportedly accepted the respected pastor into its network. A transfer to a big-city conference might seem a promotion, but in the Methodist Church, conferences were often very big tents. But Rev. Anderson went directly to Memphis.

The same month of the turbulence, Anderson was in Memphis ordaining five new deacons into the A.M.E. Zion church; according to the Memphis Daily Appeal, Anderson “preached the ordination sermon, which was an able one.”

Succeeding him at Logan Temple was Rev. J.P. Jay, who was a leader in the “Grand Jubilee” held in Knoxville in April 1870 to celebrate the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing Black men the right to vote nationwide. Although Black men had been voting in Tennessee for three years, it was an occasion for a celebratory parade, and speeches. Rev. Jay “made a fine speech and was vociferously cheered.” Accompanying Jay were several of Anderson’s old friends, allies, and perhaps rivals, including educator James Mason, attorney W.F. Yardley. Rev. G.W. LeVere who gave a speech “which was alike honorable to his head and heart.” Also prominent there was Dr. J.B. Young, who was the chief marshal.

Anderson was absent. No longer in Knoxville either as resident or visitor, by early 1871, Rev. Anderson was in Nashville serving as chaplain for the weeklong Colored State Convention, opening each session with a prayer. Later that year, he called for a Southern States Convention to address racial problems in the South; announced for Columbia, SC in October.

For a while, Knoxvillians heard little of the once-popular Rev. Alfred Anderson. But in the first days of 1872, the Knoxville Daily Chronicle, Capt. William Rule’s Republican paper, ran a short article: “Meeting Thursday Night: A meeting will be held at Logan’s Chapel tomorrow evening, at half past six o’clock, for the purpose of paying a tribute of respect to the memory of Rev. Alfred E. Anderson, late pastor of Zion Church in this city, who died in Louisville, Ky., in the early part of December last. Revs. G.W. LeVere, Henry DeBose, and other will deliver eulogies on the character of the deceased.”

DeBose had replaced Jay at the pulpit of Logan’s Chapel, but probably the most personal eulogy was that of Rev. George W. LeVere, founding pastor of Shiloh Presbyterian Church, who had also been a teacher in Freedmen’s schools, and had known Anderson for years. He’s well remembered in Knoxville history.

An unsigned editorial squib in the Daily Press & Herald, a paper that was not always friendly to civil-rights leaders, remarked that the announcement of his death arrived on the same day as the announcement of the mayoral candidacy of Dr. J.B. Young. That was in itself remarkable, the first time a Black man ever ran for a higher office than alderman.

How well Young did in his bold mayoral bid, as the late Bob Booker has observed, is strangely unreported.

But the white paper, rather than noting the moment of the initiative, referred to Young’s political career as if it was enabled by Anderson’s sudden death. “The coincidence was painfully suggestive.”

***

A Memphis paper, the Public Ledger, quoted an article in the Knoxville Whig about Anderson’s divorce from his wife, Mary: “Our city readers will remember that the allegations of Rev. Mr. Anderson reflected seriously on the moral status of J.B. Young, colored, of this city … who had wrecked the domestic felicity of the couple. Rev. Mr. Anderson involuntarily exiled himself from the city as soon as the facts of the case were made known to him, and is now in charge of a church in Memphis. The decision of Chancellor Temple [Judge Oliver Perry Temple granted the divorce] is most gratifying to the numerous friends of Rev. Mr. Anderson, especially those who have known him from his youth, and who have confidence in his morality and Christian spirit.”

The story got around the country, reprinted with apparent glee in Philadelphia, Detroit, Louisville, sometimes exaggerated (the Detroit Free Press reported that Dr. Young murdered Mrs. Anderson). Some quoted what was purported to be the text of Anderson’s note to his wife, giving her to “the mogul Dr. J.B. Young.”

***

Exactly what happened to Anderson is unknown. His age is obscure, but circumstances suggest he was still a relatively young man at the time of his death. The Louisville Courier-Journal of Nov. 6, 1871, includes a short report that may be relevant to his fate.

Just south of that city on the Ohio River was a desolate place known as the Wet Woods, a swampy forest near the old Wilderness Road, about seven miles outside of town. The Wet Woods was known in the late 19th century for violent crime. According to the article, a “woodchopping” in that forbidden location led to a fight between two Black men. Getting the worst of it was a man named Alfred Anderson, no mention of his being a reverend. His assailant attacked him with a pocketknife, cutting into Anderson’s right side, “inflicting a severe and it is said dangerous wound,” reported the Louisville Courier-Journal. After a two-day manhunt, a man named Charles Williams was arrested. At that time, the paper added, “It is said that Anderson will probably die from his wound.”

Further reports about whether he died then, or whether Williams was arrested for murder, are elusive. And it’s possible the name of an unfortunate Black man in the Louisville area was just a coincidence.

In any case, the circumstances of Rev. Anderson’s death were never publicized in Knoxville. All we heard was that Rev. Anderson died in Louisville early December.

In a summary of church histories in the Knoxville Weekly Chronicle mentions Rev. Anderson in April 1873: “He was a faithful pastor, and worked with a religious zeal to build up his church.” Logan Temple A.M.E. Zion eventually built a very large church on Marble Alley, claimed credibly to the largest church building in Knoxville. In years to come it would host national conventions, as of the Afro-American League.

Anderson’s personal nemesis, Dr. J.B. Young, remained in Knoxville for a time, working with local Black leaders like attorney William Yardley, and led a rally for the re-election of President Grant in 1872. But by 1875, he was in Mississippi, where he was apparently more successful in gaining public office, serving for a time as a state legislator there, at the very end of the Reconstruction era. Later, perhaps disappointed with post-Reconstruction Mississippi, he moved to the Wild West. In Denver he was known as a “pioneer physician.” It was rumored that by 1890 he was moving still farther from cities, into Montana.

***

Anderson’s ally and eulogist Rev. G.W. LeVere remained a prominent figure in Knoxville for years; his wife died in Memphis, nursing the sufferers of the yellow-fever epidemic. LeVere remained at Shiloh until 1884, when he was offered the pastorate of a large church in Charleston, S.C. He died there suddenly in 1886. His body was brought back to Knoxville for burial and a major funeral, partly conducted by Thomas Humes, outgoing president of the University of Tennessee.

For all the promise he showed in Knoxville in the late 1860s, Alfred Anderson’s name rarely appears in print in Knoxville newspapers after his departure, except in lists of undelivered mail at the dead-letter office.

As Dr. Young moved around the country, Mary Anderson kept her name, and apparently stayed in Knoxville. She died here, just before Christmas in 1903. The Sentinel ran a short obituary, describing her as “an aged colored woman” living with her daughter, Mrs. Kattie Jones, on Dora Street in Mechanicsville. Despite the publicized divorce back in 1870, the obituary stated “the deceased was the widow of the late Alfred E. Anderson, a Methodist minister of this city.”

By Jack Neely

Leave a reply