Knoxville will have a hard time even thinking of itself without Bob Booker, who died last month. I can’t think of anyone of any race who has had a positive effect on my hometown for as long as he has. His name has been appearing in the local press since 1957, before I was born—when he became president of the Knoxville College chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Knoxville will have a hard time even thinking of itself without Bob Booker, who died last month. I can’t think of anyone of any race who has had a positive effect on my hometown for as long as he has. His name has been appearing in the local press since 1957, before I was born—when he became president of the Knoxville College chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

I grew up hearing his name, but came to know him personally a little over 30 years ago. His first big book, 200 Years of Black Culture in Knoxville, Tenn., came out just before I began writing the Secret History column in Metro Pulse, and we found ourselves at the same history-related events, panel discussions, book signings. He invited me to come over and visit Beck, and he showed me around. He had the daunting task of trying to organize thousands of items, newspapers, scrapbooks, photographs. We had long conversations on sunny mornings.

I got in the habit of calling him when I found something I didn’t know about. Over the years, he helped me on dozens of projects, often with surprising answers that made everything come into focus.

In more recent years, we were often recruited as a sort of tag team, when someone needed a broad, quick history of Knoxville. I always enjoyed it, and he claimed he did, too.

About nine years ago, I found myself in an unexpected crisis, as it became clear that the only way I could go on with my peculiar career writing about the city’s history was to create a new nonprofit to do so. As one of our first board members, Bob helped lead that effort. His presence gave the Knoxville History Project an authenticity from birth that we might have lacked otherwise.

In recent years, we’ve worked on dozens of projects together. He spoke at several of our monthly events, on Zoom and in person at Maple Hall, from a program about the centennial of the race riot of 1919 to the decidedly mixed record of Urban Renewal in Knoxville. Last summer, we were working on the Knoxville Museum of Art’s Higher Ground book, to tell the whole story of the city’s artistic heritage. Bob had a particular advantage in that regard. He kept insisting he didn’t know about art, but he knew what he liked, and he did know Ruth Cobb Brice, the schoolteacher who became one of Knoxville’s best-known African American artists, and maybe our best-known surrealist, who died back in 1971. He knew her personally, as a longtime neighbor on the fringe of the Bottom, and remembered her vividly. He also helped with our recent driving tour of Mechanicsville, answering a question about the changing course of College Street that was baffling from the written sources.

He left us quickly. He was a few weeks shy of 89, but never seemed like an old man.

***

Historians are rarely historic. People who write history generally don’t make history, but when they do, they’re pretty remarkable. Those that come quickest to mind are Teddy Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Bob Booker. Before he ever wrote a book or gave a presentation about Knoxville’s African American cultural heritage, Bob was an influential activist and civic leader. If he had left us 50 years ago, we would still be talking about Robert J. Booker’s legacy today. He was the bold young student who was willing to go to jail to defy injustice. He was later the one who led the return of Black leadership to public office after half a century when nearly all our political leadership was white.

Born during the Depression, he grew up in the Bottom, east of the Old City before it was the Old City, where people lived in the alleys between factories, within earshot of slaughter pens, but within walking distance of the Gem Theatre, the “colored” theater that featured second-run movies and occasional live music shows, and later attended all-Black Austin High. He grew up in a segregated Knoxville that was not ready to permit him to attend the University of Tennessee or even attend a movie at the Tennessee Theatre. It might have seemed a relief to join the Army in the ’50s, to serve for a few years in Europe. He learned to speak French.

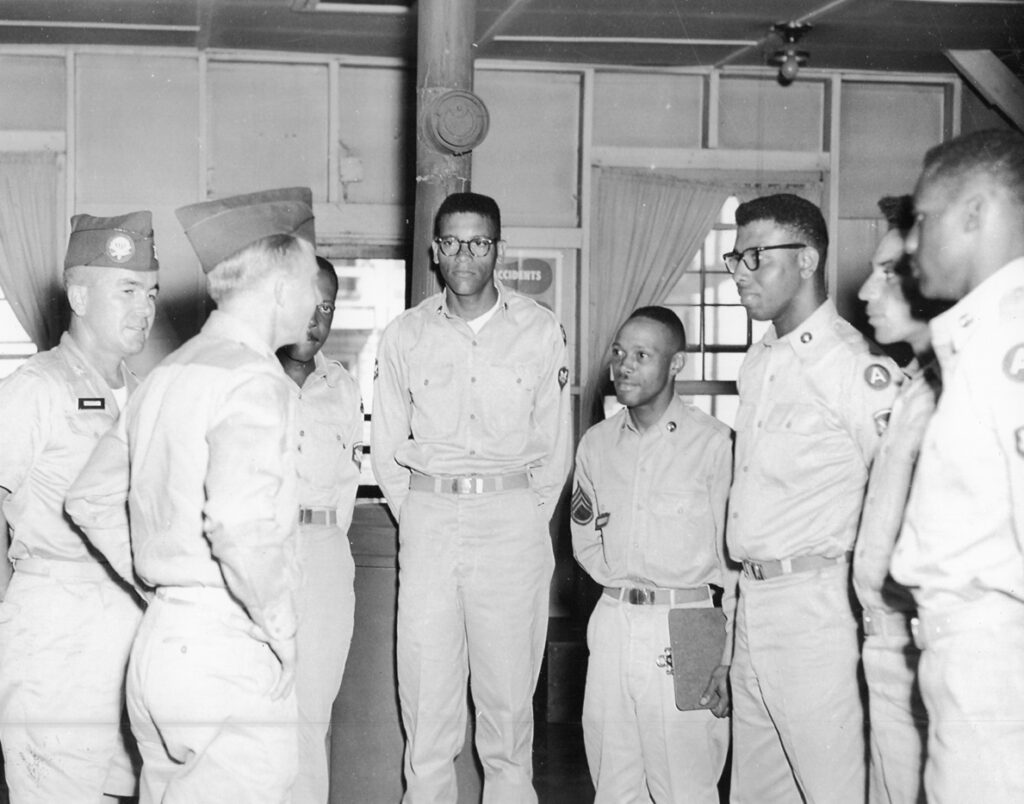

Bob Booker (center) during his army years, 1950s. (Bob Booker Collection.)

Back home as an Army veteran, he attended Knoxville College, and his tall, commanding presence made him a natural for student-body president—and as the local leader of a national movement. He saw Martin Luther King make his only public address in Knoxville, on the big lawn at KC in May 1960, and knew it was a significant moment. It was just as Knoxville’s downtown sit-ins were commencing, with Bob at the lead.

His influence was real, and serious, but he enjoyed messing with the old racially fastidious system. Once, offering a tour to a cadre of internationals visitors, he passed as a North African to slip into the old all-white Pike Theatre in Bearden. When he was arrested for trying to get into the Tennessee, he complained to the paddy-wagon driver that he was being forced to share the space with white prisoners. Segregation may have been evil, but it was mainly just stupid, and he often found it laughable.

He traveled and worked in Africa. He was a public-school teacher in Chattanooga for a while, teaching French, which he had picked up in Europe. Later he was up north for a bit working in promotions, but he kept returning to his hometown.

History will remember him forever as the first Black man to represent Knoxville in the state legislature. He investigated conditions for inmates in both prisons and mental hospitals. He defended the Highlander Center from charges of Communism, and tried to pry a fair share of state money for Knox County projects. He was the first I know of to raise the alarm that Urban Renewal was going too far, and needed to stop. After a few years of witnessing what partisanship does to ideals, he tried other things.

He made some interesting connections, and was a mayoral aide during a critical era. He helped host Muhammad Ali’s visit to Knoxville, but he knew the late John Lewis much better, long before he was a legendary congressman. In his political career, Bob got to know Vernon Jordan, Julian Bond, Barbara Jordan, and others. He became a bridge between multiple factions that came to understand and respect each other better thanks to his efforts.

That was all more than half a century ago. Think of what he’s done for us since then.

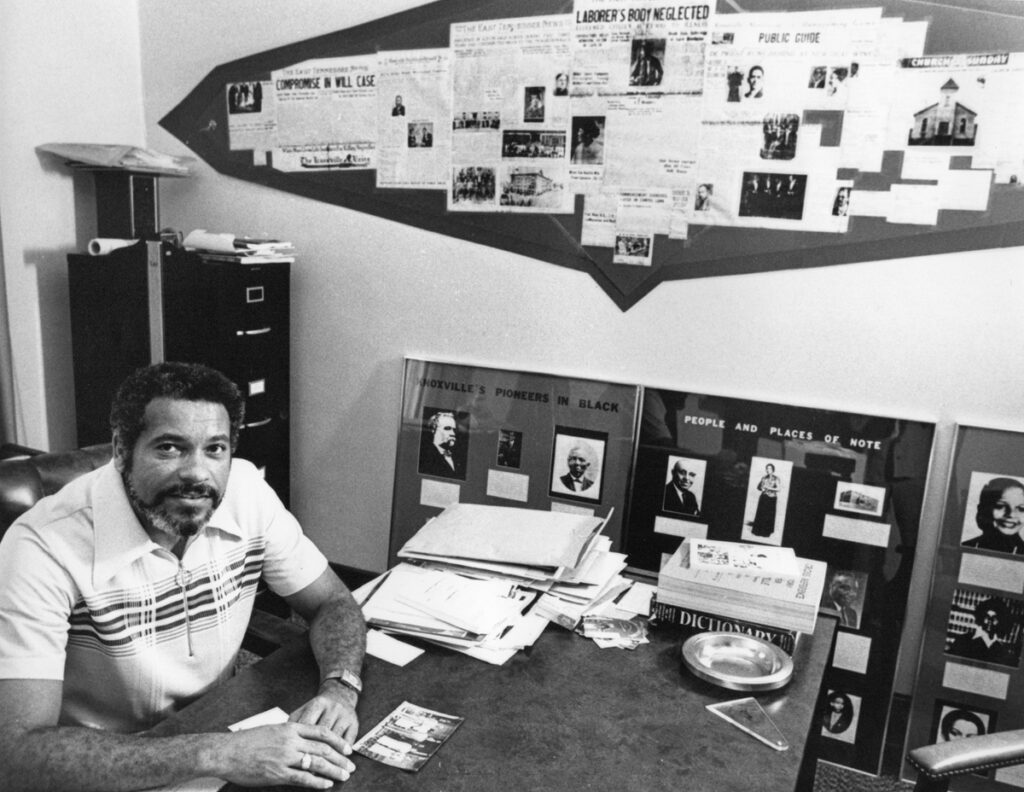

Bob Booker during his time as Executive Director of Beck Cultural Exchange Center. (Bob Booker Collection.)

His long tenure at the helm of the Beck Community Exchange Center did much to help define that unusual civic asset for many of us. And he has researched and written hundreds of newspapers articles, first for the old Journal and then for the News-Sentinel, and along the way he’s written several books that I’ll be referring to for the rest of my life. Books about long-neglected communities in Knoxville history and also about Bob’s beloved alma mater, Knoxville College.

As a historian, Bob opened a door for a whole realm of people and stories that might have been forgotten otherwise.

Memories of people, even important people, tend to evaporate as the years go on. A familiar old hymn includes a chilling couplet: “Time, like an ever-rolling stream, bears all its sons away / They fly forgotten, as a dream dies at the opening day.”

You can prove the truth of those lines with a walk through any big cemetery, which might present thousands of names inscribed in stone but now unfamiliar to most visitors. Many people can’t even name their own grandparents. But thanks to Bob, and his books and articles and memorable Carousel slide presentations, Knoxville knows the names of Charles Cansler, William Hastie, Cal Johnson, Dr. Henry Morgan Green, Richard Payne. Contrary to the patterns of community forgetfulness that apply to almost everyone else, these are all people who are better known today than they were a generation or two ago. Even kids in their 20s now know who Cal Johnson was. And that’s mainly Bob’s doing.

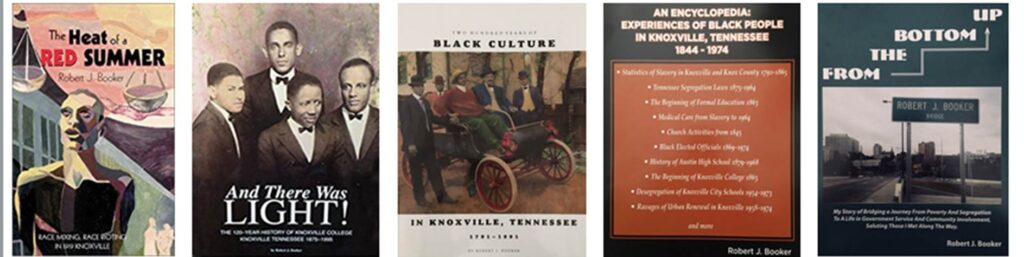

Bob Booker’s books detailing Knoxville’s African American history. Available at Beck Cultural Exchange Center.

He wrote several invaluable reference books, but the best read of all of them is his most recent, his autobiographical From the Bottom Up, playing on the nickname of his childhood neighborhood. The book encapsulates his life, but concentrates on the most dramatic scenes of his youth. As you read it, you can hear his familiar baritone voice, and occasionally his distinctive chortle.

I’m grateful for it. I’ve relied on Bob for help with a lot of questions over the years.

He wasn’t necessarily easy to get in touch with. He’s the only person I knew who published his home phone number in the newspaper. Whether he would answer was always the question. Even in his 80s, he was known to ramble far and wide. He was often out in the back yard gardening, out in the community giving a presentation, downtown in the McClung Collection’s microfilm room, singing in a bar, or out for lunch with friends at Rankin’s. Just in recent years, his phone number had something that sounded like voicemail. Did he ever check it? I’m not sure. The trick was to catch him the right time of the day, usually early in the morning or late in the afternoon, but it was kind of like bowling; you never knew whether you were going to connect. My likelihood of catching him at home rose slightly with the years. When I succeeded, I was in for a great conversation. “What you know that’s good?” he’d say, and I’d try to come up with something.

I respected the fact that he never had email, or a cell phone, or a home computer, and that he was never tempted by so-called social media. It was one thing he and I had in common: we were both, to slightly different degrees, technophobes. Once when we offered to load his old 1980s Carousel slides into a digital Power Point presentation, just for one event at Maple Hall, he politely but firmly declined.

There’s a lot to say about Bob without getting to his fascinating hobbies, like gardening and old movies and classic records. Many looked forward to his two-hour radio show spinning platters on WJBE, in which he would present both familiar and obscure pop and R&B, and say a few things about the performers as if he knew them personally, and maybe he did.

About five years ago, I was drinking beer in a crowded, smoky bar called Marie’s Olde Towne Tavern, on karaoke night. Mr. Robert J. Booker was there, singing old Ray Charles or Hank Williams standards. When he sang, everybody shut up. There were 30 or 40 people there, and I looked around at the white faces and wondered how many of them knew who this man was, that he’d led bold and successful demonstrations against segregation, that he’d been elected to important public offices, that he’d written books. Bob could have introduced himself as an author or a civil-rights legend, but he didn’t. That night, and many others, he was happy to be the best deep baritone in the room, nothing more, and that’s what he got applause for.

Now we’re waking up in a Knoxville without Bob Booker, and he’s leaving us with a void that no one person can fill. We’re thankful we still have his books, and his perspective.

But remembering Bob, we’ll all be obliged to follow his example, when we can. We’ll have to be a little wiser, a little kinder, a little bolder. And always, tell the good stories, so they won’t be forgotten.

By Jack Neely

Leave a reply