A nice bowl of goldfish, nogless eggnog, the frantic scramble, a celebrated female impersonator, a live theatrical dramatization of an aeroplane crashing through a Mexican house—and a momentous meeting at the top of the Burwell

It was Christmas season again. A lot like others, but every year brought something different. And this Christmas season would be, in a way not recognized for many years to come, momentous.

Knoxville was a city of over 80,000, sometimes even claiming it had more than 100,000, but still getting used to its recently annexed new suburbs, including a large area across the river known as South Knoxville, and the Looney’s Bend area not yet redubbed Sequoyah Hills.

Of course, those newly incorporated suburbs were almost all white. Although modern and even progressive in other ways, the new neighborhoods came with “covenants” assuring that only white people would ever live there. Such real-estate contracts were common throughout America. Some semi-rural African American communities survived, in niches between the white suburbs, but segregation, stricter than it had ever been in the previous century, concentrated people of color in the limited areas where they were allowed to live and run businesses, especially in Mechanicsville, the old Cripple Creek area becoming known as the Bottom, and East Vine Avenue. East Vine, in particular, was then developing a lively sense of its own culture, with dance halls, pool halls, barber shops, and drugstores, and street musicians like teenagers Howard Armstrong and Carl Martin. The Gem Theatre was central to everything, with both motion pictures and live jazz and blues shows. (Unfortunately, the Gem didn’t often advertise in the daily papers, so it’s hard to know what they were offering that holiday season.)

Meanwhile, across town, nationally respected Knoxville College was thriving, expanding with new athletic fields, while known off campus and even in other states for its celebrated singing quartet, which gave a holiday presentation at the YMCA.

The larger university on the Hill was growing rapidly, becoming more part of the city’s consciousness, especially through athletics. Shields-Watkins Field had no stadium but only bleachers, with a seating capacity of 3,200, more than the total number of students at the time. On rare occasions it was almost full. By December, though, the Vols had already concluded a lackluster year under Coach M.B. Banks, losing to Vanderbilt, Georgia, and Army, and tying with Maryville College. Football fans were paying more attention to the Fighting Illini, with the nation’s latest football hero, Red Grange. But there was more about the upcoming baseball season, and Fred Moffatt’s high hopes for the Knoxville Pioneers team at Caswell Park.

If Knoxville didn’t have its own football champion, it had a national legal champion. Judge E.T. Sanford, whose distinguished gray beard had been a familiar sight around UT and downtown for decades, had recently moved to Washington to be sworn into the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile another former Knoxville lawyer, former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo, was also in the national spotlight, announcing that Christmas that he was running for the Democratic nomination for the presidency. East Tennessee remained a Republican bastion, though, and Congressman J. Will Taylor announced that month that he was backing Coolidge.

Journal & Tribune, December 14, 1923.

It was an exciting new era of airplanes and automobiles. By then, with three airfields, Knoxville had lots of both, but many more of the latter. More affluent Knoxvillians had a car in 1923 than ever before, an estimated 10,000 of them in the city. After 15 years, Ford’s Model T was now a familiar sight, all of them black, of course, but with little changes introduced each year. There were also Chevrolets, Hupmobiles, Maxwells, Reos, Nashes, Hudsons, Packards, and luxury Marmons. “You can’t cross the street without playing tag with two or three of the machines,” one reporter remarked.

Serious drivers joined the Knoxville Automobile Club, excited about the idea of new paved roads connecting Knoxville to the nation and even to points of interest in its own region, in ways it had never been connected before, by the new Dixie Highway and other routes. In the early 1920s, citizens were especially curious about the steep ridges to the south, sometimes visible through the coal smoke. Most Knoxvillians had never been to the Smokies, but the automobile—and, critically, paved roads—promised to make the mountains much more accessible.

Radio had arrived, perhaps not as exciting as it was last year, when it was brand new and jaw-droppingly astonishing—and not as important as it would be later in the decade, when many more people owned radios and listened to them at all times of the day. But WNAV was broadcasting a few hours, usually in the early evening. Much of its programming was live local choral music, classical, operatic, and religious, and usually just for an hour or two in the evening.

People with radios sometimes found it more fun to try to pick up bigger-city stations, Pittsburgh’s KDKA, New York’s WGY, Atlanta’s WSB, and Detroit’s WWJ, all of which could be received in Knoxville well enough that their listings appeared in local papers.

Radios, odd-looking wooden boxes with knobs, were going for $6, and advertised as Christmas gifts.

Knoxville Journal & Tribune, December 10, 1923.

Most radios looked like homemade contraptions. Phonographs, a much nicer gift, looked like polished furniture. Sterchi’s sold three different makes of them, Victrolas, Brunswicks, and Edisons, and you could buy them on terms, with weekly payments. The Edison model alone came in seven distinctly different models, some of them resembling antique credenzas.

Invited to speak on WNAV was an interesting newcomer, the new city manager, a nationally celebrated urban planner who arrived in town just days before Christmas. The new electric medium seemed to match his new ideas. The still-new city-manager charter remained controversial, and conservative factions were already organizing to oppose it, even before they knew what this Louis Brownlow was up to. A Missouri-born relative of the old “Fighting Parson” Brownlow of the Civil War era, this modern Brownlow was keeping his cards close to his vest that December, but in years to come, his progressive ideas for the city would foment an anti-tax backlash. All he was promising in 1923 was that there would be “No politics in City Hall.” (City Hall was then still a nearly cubical building on Market Square, but soon to move, under Brownlow’s supervision, to the vacated School for the Deaf building around the corner.)

***

People were wary of Christmas, dreading the dependably maniacal shopping season, described by a local writer that month as the “same old frantic scramble, exhausted and half-crazed clerks, desperate shoppers pawing over the oft-pawed-over articles rejected by forethoughted shoppers; excited wives, irritated and overloaded husbands….”

Perhaps seeking solace, a Journal & Tribune feature looked to the past for some perspective, asking elderly folks to share memories of an old-fashioned Knoxville Christmas, as celebrated about half a century before. Captain William Rule, a Union veteran of the Civil War, was then 84 years old, and happy to oblige for the paper of which he was still the editor. Back in the 1870s, he said, Christmas had “more of the carnival spirit than today—streets filled with shooting fireworks, blowing horns, ringing bells.”

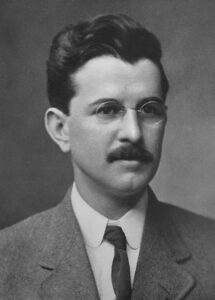

William Rule (1839-1928), longstanding editor of the Knoxville Journal & Tribune, circa 1925. (McClung Historical Collection.)

Rule seemed a little perplexed that the public observation of Christmas in 1923 was sometimes more solemn than it used to be. “The spirit of reverence which of late years seems to have entered more into the observance of Christmas was generally lacking” in the 1800s, he said: “except in churches.” He remembered Christmas-morning hunting parties, and an occasion when a Civil War cannon planted on UT’s Hill as a relic was detonated on Christmas Day. Old women remembered when the holiday “took the form of a dance,” and “hoop skirts and tightly corseted waists seemed not to have interfered in the least with the grace of the debutante whose slippered feet kept pace with the music, oft-times till early dawn.” Some also claimed that snow was much more common at Christmastime back in the ’70s, and that horse-drawn sleighs with sleighbells, not just an ideal from festive songs and Currier and Ives prints, were once really a common part of the Knoxville Christmas.

Although bits of those old traditions remained in the Jazz Age, much of the old-timers’ memories of deafening street clamor, general irreverence, and all-night parties might have been surprising to Knoxville flappers who read that newspaper story.

“But what will be the verdict of those who in the good year 1973 inquire of the Christmas celebration of 1923?” The morning newspaper assumed Knoxvillians of the distant future would be curious to ask.

The Fred Morgan Store seemed to recall Capt. Rule’s memories when it advertised “a real Christmas with plenty fireworks”—firecrackers, skyrockets, and Roman candles. Their store was at Greenway Station, off North Broadway at Sharp’s Ridge. They could get away with it, because they were just outside of city limits, where fireworks were banned, as usual since they got out of hand back in ’93. Police Chief E.M. Haynes made that clear with a fresh directive.

But the main noise that older people might have found unsettling came from cornets. It was the jazz age, and jazz was everywhere. The big, stylish, countryside hotel at Whittle Springs advertised itself as the Playground of the South, and proved it with a seven-piece house jazz band known as Whittle’s Royal Troubadours. For several nights in the middle of December, Whittle featured Harry Yerkes’ Musical Bell Hop Orchestra, playing light jazz until midnight. The New York band, “one of the greatest dance orchestras in the country,” were among America’s early jazz recording artists, and they had several records out. (The new dance known as the Charleston had been introduced just a few weeks earlier, but Whittle assured stoic East Tennesseans, “You don’t have to dance.”)

***

Some things didn’t change much. Market Square, a rare spot where Eastern European immigrants, African Americans, and mountain people mixed every day, was still central to Christmas. The Journal & Tribune described “animated scenes on Market Square … Country people are delivering diversified lines of produce and many wagons from the mountain districts are delivering apples, walnuts, evergreens—cedar, pine, holly, spruce, mistletoe,” all for Christmas decorations. Also there was a traditional holiday-season offering not always seen other times of the year. Bear meat was apparently a Christmas tradition in some families, and was available on the square for $1 a pound, much more expensive than any other kind of meat. Local reporters called Knoxville’s Christmas market “unique” because of its mountain sources. Although the Smokies were still forbiddingly difficult to reach by conventional means, Knoxvillians met mountain people on Market Square.

In 1923, you could buy tropical fruit in Knoxville, but it was sometimes hard to find. Reich’s advertised “another carload of sweet oranges,” plus apples, coconuts, raisins, dates, figs—and, of course, that American fruit, cigarettes.

Mayo’s downtown location, near Market Square, sold mainly seeds and farming supplies, but offered a special holiday attraction, declaring that “a nice bowl of goldfish would be appreciated by anyone.”

***

It was an exciting new era of unpredictable entertainment, as movie houses like the Strand, the Queen, and the Gem specialized in movies, but offered some live entertainment on the side. On Christmas Eve, the Strand, on Gay near Market Square, featured the new film, Slave of Desire. Subtitled “The Golden Lure of Strange Quests,” it wasn’t necessarily holiday fare: a bizarre tale of forbidden love, suicide, and a fatal avalanche.

The Lyric Theatre, the 50-year-old venue that locals remembered as Staub’s Opera House, was the city’s biggest and busiest theater, despite the presence of the Bijou, just across Gay Street, and the new Riviera, a couple blocks down the sidewalk, that showed mainly movies, but still with some live music and vaudeville.

The Bijou was also hosting an impressive array of holiday shows, including several single-night touring-company versions of Broadway musical comedies and romances—The Clinging Vine, a comic satire by Zelda Sears about gender roles in business and romance, featured 48 singing and dancing performers.

Knoxville News-Sentinel, December 27, 1923.

However, the same holiday season brought, to the same stage, a notable boxing match. Held one week before Christmas Day, the bout was claimed to be the “biggest staged in Knoxville history.” Similar claims had been made for several fights, but that match does appear in official national online boxing records today. The contenders were Georgia teenager Young Stribling and Billy McGowan, “idol of Knoxville fight fans.” Stribling, who would turn 19 the day after Christmas, won the eight-round battle, every round, as determined by a panel of sportswriters, but local hero McGowan was “just too game to allow a knockout blow.” (Although only 166 pounds during the Knoxville fight, Stribling would be a contender for the national heavyweight championship. He later fought Italian heavyweight champion Primo Carnera and, in a bout for the top honor, barely survived a pummeling from German boxing legend Max Schmeling. Stribling was still seeking the championship in 1933 when he died in a motorcycle wreck.)

Journal & Tribune, December 16, 1923.

But every Sunday this same Bijou Theatre known for bloody fights and wacky musicals was reserved for the congregation of First Baptist Church. Their original high-steepled Victorian church on the 600 block of Gay Street was being demolished as they built a new church in a very different style on Main, and until it was finished, they were at the Bijou.

***

“If it’s a He-Man or a Real Boy,” went the ad, “the place to go is Athletic House,” at 522 S. Gay. There they sold guns and golfing equipment, toys and “wheel goods.” The manager of the new store was Frank Callaway, recently retired as an infielder for Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. For many Real Boys, he was, in himself, a good reason to visit the store.

Speaking of wheel goods, to amuse the shoppers, the Gay Amusement Co. advertised roller skating every night on North Gay Street. And Greenlee’s Bicycles, at both locations—Asylum Avenue and North Central—were selling National and Pierce models. Woodruff’s on Gay sold velocipedes, which at the time meant large-wheel tricycles.

Charities were out in full force, with the Empty Stocking Fund, this year featuring a Dec. 23 concert by Chicago baritone Carroll Ault, at the Lyric.

Every year seemed to bring a fresh new charity, and in 1923, it was the Birthday Park fund. The idea was to establish a new city park for disadvantaged children, with funds donated to honor the birthdays of citizens, many of them children, who did some of the fundraising. By the end of 1923, it was unclear where the park would be located, with North Knoxville and Bearden suggested. As it happened, it would coalesce on a hillside beside Chilhowee Park. It would evolve, many years later, into something called the Knoxville Zoo.

***

Although local saloons had been banned 16 years earlier, Knoxville was still getting used to the fact that liquor was illegal, even during the holidays. Wags joked about “nogless eggnog,” but there was a lot of winking going on. Bootlegging was a way of life. Knoxville’s early ban had given the city’s underworld a head start. When national prohibition arrived, Knoxville already had established underground networks.

Of course, some affluent households got around the liquor ban with international travel, especially to one favorite vacation spot about 1,000 miles due south. Havana was a stylish destination for Knoxville’s wealthy; Eugenia Williams and her husband, Gordon Chandler, had been there earlier in the year, and members of the Tyson family announced they were spending Christmas in Cuba. You could buy a ticket there at the Southern Railway station—despite the fact that a critical part of the trip was not by train.

There was still some holiday trouble at home, if much less than in previous eras, when Christmas week often averaged a murder a day. The 1923 holiday season witnessed the mystery of the disappearance of Dr. J.S. Jones, a Methodist pastor from Maryville. He’d been on a hunting trip when he went missing a few miles downriver. The leading theory was that he’d been mistaken for a revenuer.

On Saturday night, Dec. 22, East Jackson Avenue restaurant proprietor Roscoe Bates had an argument with George Mackey over a bootleg whiskey deal. Mackey got aggressive. Bates was wearing his holster, and reached for his gun, but realized he’d left it at home. Mackey shot Bates four times, and the restaurateur died at Knoxville General Hospital, a few blocks away.

House Mountain saw a holiday season gun battle between county deputies and moonshiners; the latter got away, but not with their fresh batch of apple brandy.

And at 2100 McCalla, Charles Gentry had gotten up early in Christmas Eve morning, had made a fire and was reading the paper, when something whistled past his head, tore through the newspaper he was reading, ricocheted off a wall, went through the dining room, hit the breakfast-room door, and dropped at the feet of Mrs. Gentry. It was a .32 bullet, origin unknown.

Most crimes were less serious. Pickpockets were an old Christmas tradition, especially on crowded Market Square, and retailers were told to be on the lookout for a fellow with a false mustache, who was passing bad checks.

An unnamed Black man was jailed for public drunkenness. Many men of both races were; it was a holiday tradition. But as it turned out, this particular inmate at the city jail was a businessman. He had hardly arrived in the big, crowded cell before he began arranging bail for his cell mates. He “summoned officers to tell them several inmates were ready to post bond.” He was, it turned out, a “duly qualified bondsmaker,” and had gotten himself jailed deliberately to drum up business. The police were flabbergasted by the gesture, but could find no statute forbidding it.

***

Christmas Day was a little bit different from today in that it was a little more broadly sociable, with society and public events. Several churches still had Christmas-morning services, even though it landed on a Wednesday. Cherokee Country Club hosted a “matinee dance” on the 25th, at 11 a.m., in its original semi-rural lodge, with a dinner buffet. There’d been several previous holiday dances there, including a Bal Masque—a Christmas masquerade—the week before.

All of Christmas week, the Lyric hosted Peruchi Players, a semi-local dramatic troupe, and its production of The Broken Wing, a love story about an American pilot crash-landing during the Mexican Revolution, losing his memory, and falling in love with his Mexican nurse. “Laughs! Thrills! Love! Sensational!” trumpeted the Lyric’s ads. “See the Aeroplane Crash through the House.”

The Lyric Theatre, formerly Staub’s Opera House, on Gay Street, circa 1921. (McClung Historical Collection.)

The plot had become well-known that fall: the motion-picture version had already shown at the Strand, four blocks down the street. But the Peruchi family gave it a more-impressive live interpretation, described as “one of the most sensational and amusing climaxes ever seen on stage,” with a “realistic aero-plane effect and startling situations.”

Peruchi Players, led by Chelso Peruchi, were formed around a talented Italian family, originally spelled Pierucci, that had roots in Knoxville before the Civil War. Members of the second and third generation had been performing here since the 1890s, but Peruchi Players was a relatively recent iteration of the footloose troupe that traveled from city to city, always gravitating back toward Knoxville for long residencies.

On Christmas Day, the Lyric featured an extra matinee presentation of their unusual play.

On Christmas evening, WNAV broadcast a live vocal performance featuring students from Knoxville High School.

Also on Christmas night, perhaps encouraged by the previous week’s popular Stribling-McGowan bout, was another boxing extravaganza. The Ring Athletic Club, in cooperation with the American Legion, sponsored six prize fights, including local favorite Tiger Toro against Battling (“Bat”) Drummond. It all took place at the walk-up boxing ring on Market Street, just south of Arnstein’s department store, in a gymnasium on the third floor above David’s Women’s Ready-to-Wear.

***

Those who gave or received radios on Christmas, 1923, may have had second thoughts about whether it was a perfect gift. A few days after Christmas, William Ashton, 21-year-old primary staffer of Knoxville’s only radio station, WNAV, prompted a crisis when he announced he was leaving to take a job in Philadelphia, part of it broadcasting from ocean liners. To Ashton, who’d done a hitch in the Navy, it may have been irresistible.

So just after Christmas, WNAV, which had introduced Knoxville to radio a year before, announced that it was going off the air indefinitely. A four and a half-hour New Year’s Eve farewell program featured several classical performers, like pianist Ruth Ferrell, and the Logan Temple AME Zion church’s Usher’s Board Quartet, that last broadcast of 1923, on New Year’s Eve. The broadcasting studio in a walk-up space in the old Deaderick Building on Market Street, co-sponsored by the Journal & Tribune and described excitedly in that paper a few months earlier, closed.

Nine months later, Ashton surprised everyone again when he returned to Knoxville, this time to launch First Baptist Church’s new low-watt station, broadcast from its own new steeple on Main Street, WFBC. Now working a day job as a mail carrier, he became better known as an evangelist.

That same New Year’s Eve brought the new Broadway musical Wildflower to the Bijou. The play, produced by Arthur Hammerstein, with songs written by his 28-year-old nephew, Oscar Hammerstein, was unusual in that it opened in Knoxville less than a year after it opened on Broadway—where it was officially still playing, at the grandly elaborate Casino, at 39th Street. A nationally popular show, its acclaim was based mainly on its songs, some of them sung by star Eva Olivotti. (She would later have a minor film career providing a singing voice for the 1929 version of Show Boat, one of the sound era’s first musicals.) The play might have evoked special resonance with the Knoxville audience, in that its female chorus were dressed as Italian hikers. More and more women were beginning to hike in the still-wild, mostly trail-less Smoky Mountains.

And that same night, a nine-act vaudeville show at the Lyric, across the street, opened at 11 p.m., featuring a 10-piece jazz band.

But the first week of 1924 brought a bigger surprise to the Bijou. Another traveling show, the Black and White Revue of 1924, a spectacle of a “symphonic jazz orchestra” and a six-saxophone band. It’s unclear whether there were Black performers involved the extravaganza. But the star was Julian Eltinge, who’d been popular in Knoxville since his first performance at Staub’s 15 years earlier. In recent years, he had become a movie star.

A popular singer and dancer, Eltinge was perhaps America’s most respected female impersonator, though he didn’t like that term. To describe him, a Chicago critic had coined the term “ambisextrous.” They say this man who resembled a portly banker by day didn’t mimic women on stage, he became them.

Knoxville Journal & Tribune, December 31, 1923.

The Knoxville show, at the end of the Christmas season of 1923-24, promised that Eltinge “will entertain the theater patrons with the fads and fancies of the fair sex. A complete extensive new wardrobe has been procured for this season’s tour and positively the newest creations from the ateliers of the leading modistes.” Unfortunately, the papers rarely ran reviews of one-night shows, so we don’t have descriptions detailing what he did at the Bijou.

***

With so much going on, you might be forgiven for not noticing that something momentous was afoot high in one of downtown’s skyscrapers, just before Christmas.

The law offices of Hugh B. Lindsay were on the top floor of the tall, slim, Burwell Building. Fifteen years earlier, it had been Knoxville’s tallest building, but a decade ago it yielded that superlative to another bank building diagonally across the street, the Holston. It was not yet home of the Tennessee Theatre, although a project to build a major “motion picture palace” behind the Burwell was in the works.

Judge Hugh B. Lindsay. (KHP.)

At 66, Judge Lindsay was considered an elder statesman among lawyers. Once a gubernatorial nominee, former U.S. district attorney, former chancellor, former attorney general, Lindsay had recently been the ablest fellow to lead the roast of Judge E.T. Sanford as he left town to join the U.S. Supreme Court.

Gathered in that top-floor room, on Friday, December 21, were other prominent men, several of whom were members of the Knoxville Automobile Club. The apparent leader of the project was Willis Davis, who had moved here from Louisville, Ky., seven years earlier. He was president of the Knoxville Iron Co. in Lonsdale, but at the time lived with his wife, Annie, in Fort Sanders Manor, the courtyard apartment building on Laurel Avenue.

The meeting had a lot to do with a bold scheme he and his wife had been talking about.

Also there was Forrest Andrews, 43, a home-schooled farm boy from the Nashville area who made it into Vanderbilt and a career as an attorney and businessman with an interest in public education.

J. Wylie Brownlee, Journal & Tribune, November 19, 1913.

Originally from Western Pennsylvania, businessman/realtor J. Wylie Brownlee had been a vice president of the National Conservation Exposition of 1913, during which he was also president of Knoxville’s Board of Commerce. He lived on Martin Mill Pike, but was sometimes described as a resident of Gatlinburg, and was also a member of the Appalachian Club in Elkmont.

Even though three weeks earlier he’d been seriously ill, Daniel Clary Webb, the attorney from Middle Tennessee, attended the meeting. Son of legendary boarding-school master “Sawney” Webb, D.C. Webb was a former Juvenile Court judge, and one of the first residents of the new suburb becoming known as Westmoreland; he was soon to build the waterwheel at Westland. (His four-year-old son, Robert, would found Knoxville’s Webb School.) D.C. Webb was now president of the Rotary Club, which would be a major player in the plans sketched out in that room.

Cowan Rodgers was there. The Knoxville native who had introduced the automobile to Knoxville, with a couple of noisy homemade jobs down on the Bowery in the late 1890s, was now a prominent auto dealer, specializing that year in the Hudson and Essex lines. He was now, fittingly, president of the Knoxville Automobile Club—as he was also rousing some excited speculation that he might run for governor.

Another lawyer, James Bascom Wright, was a former newspaperman who had once worked with Wilson’s Secretary of the Treasury, W. G. McAdoo; he was now attorney for the L&N Railroad. He had a home in Elkmont, but his dreams for the Smokies would differ sharply from those he met with that day.

Col. David Chapman. (KHP.)

And there, not necessarily the most prominent attendee in 1923, was David Chapman. At 47, the short, bespectacled pharmaceutical executive had trained recruits during wartime, and may have found his military habits useful for marshalling the personnel and resources for a major task proposed that evening. He had been involved in numerous humanitarian projects around town, but could not have expected to have found his name on a very large mountain.

Several of those early leaders, especially Brownlee and Chapman, had held leadership roles in the National Conservation Exposition of 1913. Held at Knoxville’s Chilhowee park over a two-month period, it was the world’s first big convention with a conservation theme, and drew one million visitors. It had closed 10 years before the meeting in the Burwell Building, but its ideals likely informed the discussion.

The small group meeting in Judge Lindsay’s office had two goals. The Knoxville Automobile Club had been hot to plan more paved roads in the region, and were especially keen on getting one through the mountains, all the way to the Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. (The new association, which included several members of the auto club, also made that a priority.) But their other, more ambitious goal, was was to create “the first national park east of the Rocky Mountains.” To be fair, by then there was one small national park up in Maine, but these men had something grander in mind, a project taking in half a million acres, straddling two states. The Smoky Mountains, visible in the distance on a clear day, but difficult to reach, privately owned and little known to most Tennesseans, should be protected forever, they said, as a public asset.

To that end, as frantic holiday shoppers swarmed the sidewalks of Gay Street down below, they founded the Smoky Mountain Conservation Association (later the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association.)

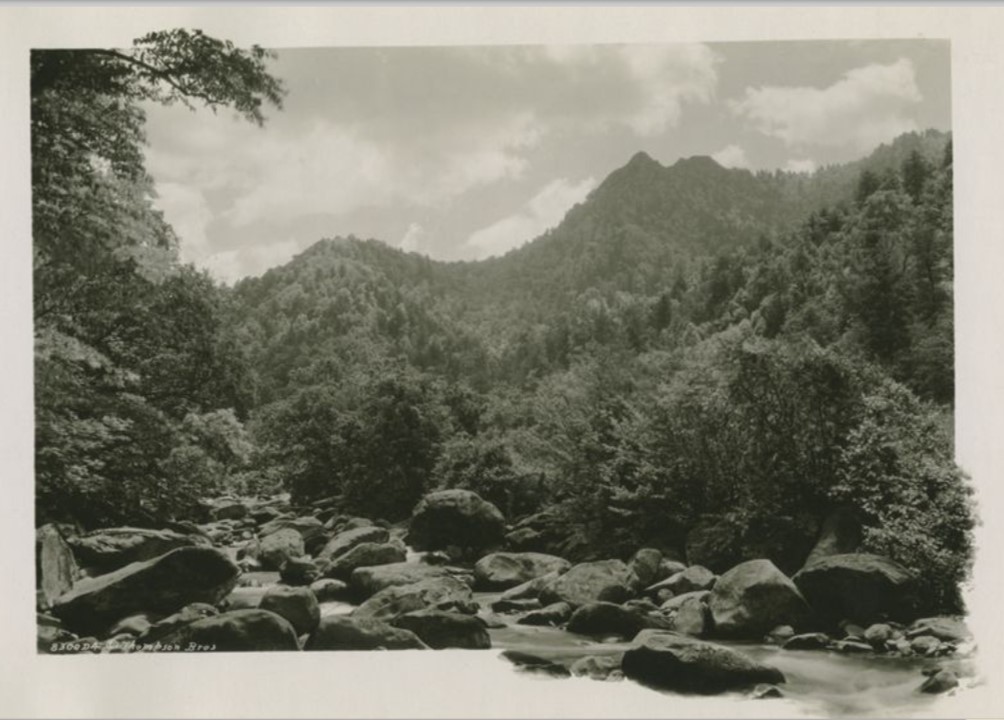

They settled on some priorities, including forming an executive committee charged with approaching the larger landholders, especially the timber industries, about acquiring some or all their Smokies properties. They also discussed collecting photographs of the Smokies to promote the idea, mentioning in particular those of the Thompson Brothers, Jim and Robin, who had already expressed some interest in the subject.

“Approaching Chimney Tops,” a pre-national park photograph in the Smoky Mountains by Jim Thompson. (KHP.)

At the same time, the Knox County Federated Women’s Clubs expressed support, and promised to meet soon to discuss the prospect. A few politicians signed on. U.S. Senator John K. Shields disliked Wilson’s League of Nations, but liked the Smoky Mountains park idea.

Over the next several years, until the federal government, finally convinced it was a great idea, took it over, the association founded in Judge Lindsay’s office was the primary author and custodian of what became the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Annie Davis. (GSMNP Archive.)

There’s no mention of any women attending that lofty meeting in the Burwell, but it had been a woman’s idea; by early leader Willis Davis’s own account, it was all the brainchild of his younger wife, Annie, the Bryn Mawr alumna and mother of two, who had proposed a national park in the Smokies after they’d taken a trip out to see Yosemite and other great national parks in the west. Proposals to conserve parts of the Smokies as a harvestable national forest had been on several drawing boards over the years, but the Davises’ proposal was more ambitious—and closer to what actually came to be.

As it happened, her husband, who attended that meeting in the Burwell 100 years ago, wouldn’t live to see the full fruition of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, but Annie would. Annie Davis, who was active in Knoxville’s League of Women Voters, was progressive in other ways, supporting the controversial city-manager form of government, and was apparently convincing in public that a few months later, her campaign to be the region’s first woman to be elected to the Tennessee state legislature was successful. In her role as legislator, she did much to further the cause of a national park in the Smokies.

But in December, 1923, the Knoxville last-minute Christmas shoppers down on the street, especially those who didn’t read the paper past the front page, didn’t yet know what those lawyers and businessmen were cooking up at the top of the Burwell, or that their region was about to change, with what would amount to an enormous holiday gift to the world.

The Journal and Tribune assessed the holiday:

“With humdrum cares thrown to the winds, and memories of strife relegated to the background at last, Knoxville celebrated such a happy, peaceful Christmas yesterday as was observed before the world was wrapped in conflict. Holly wreaths hung in the windows of hovel and mansion, and … human kindness shone on the faces of the hundreds who flocked the downtown business section, and the happiness of children showed that the day had lost none of its yuletide meaning….”

By Jack Neely, December, 2023.

Leave a reply