THE MYSTERIES OF A KNOXVILLE THANKSGIVING

It’s supposedly a simple holiday, dating back to 1621, and the Pilgrims, who sought simplicity. But most sources claim that despite Tennessee’s plenitude of wild turkeys and pumpkins for pie, we didn’t celebrate the annual holiday here until 1855, the era of railroads and gaslights.

Wild Turkey, undated. (Library of Congress.)

And its date was never securely established until after World War II. What happened here, on those first Thanksgivings, on the third Thursday or Fourth Thursday, or last Thursday of November, or the first Thursday in December, depending on the year, or in one case the last Sunday? When did we pull up a chair and join the feast?

We may never know, with certainty, but it was complicated, murky, and occasionally political. And maybe we should challenge Wikipedia’s blanket statements, because it does appear that Knoxville had something called Thanksgiving several years before 1855.

In 1819, Knoxville newspaper readers learned that Gov. DeWitt Clinton of New York recommended Dec. 22 as a “day of prayer and thanksgiving in that state.” He was governor again eight years later when he declared Dec. 12 would be Thanksgiving Day. Both times got mentions in the Knoxville press. (Clinton and his Uncle George, who was vice president, are the two prevailing theories about how Clinton, Tenn., got its name.)

In 1826, a complicated short story reprinted in the Knoxville Enquirer included a soldier’s plea for furlough “to keep thanksgiving and eat pumpkin pies with his friends and the pretty lasses in Connecticut.” It’s hard to understand the context, but it may be the first time pumpkin pie was mentioned here in conjunction with Thanksgiving. Were Knoxville newspaper readers familiar with that concept?

In the first half-century of the state, mentions of Thanksgiving as a holiday celebrated anywhere in Tennessee are extremely rare.

But then there’s this outlier. Apropos to nothing, in the month of June, 1833, the often-surprising Knoxville Register, run by editor-publisher Frederick Heiskell, formerly of Hagerstown, Maryland, ran something darkly humorous and deeply cynical. It’s called “Thanksgiving Day— A Parody.” It’s the first of three poems under the heading Poetry, on the center of the front page. We’re reprinting it, without permission, with the original spellings intact:

Turkies meet their fate and die

Chickens turn to chicken pie

Geese no longer gabbling fly

Bording clouds and rain.

Don’t you hear the proclamation

Bringing barnyard desolation—

Death to half the feathered nation

On thanksgiving day?

Seize, each glutton, seize a chair

None but gluttons can be here

May heaven bless the glorious fare

Clatter knives and forks.

Wha’ for turkies roast or raw

Would not jackknife strongly draw

Glutton stand or glutton fa’

For Heav’n’s glory.

Strutting turkies, turkies meet

Pompous geese, stuffed goslins meet

Chicken-hearted boobies eat

Brother chickens now.

Eat the broken fragments up

Gormandizers—seize the cup

Here’s a health—hic-hiccup

All is over now.

It’s signed only Ut. Obs., which may be some obscure Latin abbreviation for some wag who didn’t want his name attached to that verse. It’s possible or likely it was written somewhere outside of Tennessee. But I’ve done some searches and can’t find it published elsewhere. It’s interesting if disputable evidence of two things, one that there was a clever fop in beleaguered Knoxville, hardly a generation removed from frontier days, a half-forgotten former capital town with poor river transportation, no railroad, and no clear future. It might also seem evidence that Thanksgiving dinners were familiar here, with the same association with overabundance and overeating by which it’s known today. Even if it were reprinted from some other now-obscure source, Heiskell seems to have assumed that Knoxville’s 1,500 inhabitants had enough experience with Thanksgiving Dinners to get the joke.

But it seems to describe not just familiar Thanksgiving customs, but a weariness of the whole idea of Thanksgiving, and a suggestion of its religious hypocrisy. The poem’s lack of reverence and even respect for the holiday and its celebrants may suggest that in Tennessee Thanksgiving was still a distant, Yankee think that local readers had only heard about. Newspapers always had a tenuous hold on solvency, even then, and few editors would eagerly alienate their subscribers at the top of the front page. But it’s always safe to make fun of the habits of people who are far away.

In any case, there’s not any very clear description of a Thanksgiving dinner in Knoxville in the decades before that, or for a decade after.

But in the next few years, the same paper, run by different people from farther north, would extol Thanksgiving as an ideal. As had been the case for years, references to Thanksgiving in northeastern places, especially New England and New York, made it clear that Knoxvillians had heard of Thanksgiving, even if they didn’t celebrate it.

In October, 1840, for example, the Register reported that the governor of New Hampshire appointed the 12th day of November as a day of thanksgiving and prayer. But same year a reference to a “day of thanksgiving” in November could be misconstrued.

“One day of thanksgiving should be set apart throughout the whole land, for the blessing thus bestowed us by a kind and beneficent providence.” That line appeared in the National Intelligencer, a generally conservative Whig newspaper published in Washington, D.C., to be reprinted in the Knoxville Register. Considering it appeared in Knoxville on Dec. 2, we might assume that it had to do with the holiday. But it’s a political column praising God for Harrison’s defeat of Van Buren in the recent presidential race. “The history of the last 12 years [that is, the Democratic Jackson-Van Buren era] will be read with gloom and sorrow by the future patriot of this country….”

The Knoxville Post referred to a Thanksgiving Ball at an “Insane Hospital” in 1841 in Augusta, Maine. The following year, the Register remarked 200 couples marrying on Thanksgiving Day, 1842, in Massachusetts. But sometimes years would go by with no obvious reference to the day.

In 1846, the Knoxville Register was located in a building on the southeast corner of Main and Gay, about where Riverview Tower is. Its editors and publishers were James and John L. Moses, both born in Exeter, New Hampshire. James had learned the publishing business while working as a printer in nearby Boston. The two had come to Knoxville at the behest of Massachusetts-raised Perez Dickinson, to run a newspaper here. They did, and at the same time co-founded Knoxville’s first Baptist church—something that, believe it or not, they found lacking in Knoxville—but at about the same time they seem to have become enthusiastic about introducing, or reviving, the New England tradition of a Thanksgiving holiday in Tennessee.

It would appear that it was something people knew about, perhaps even remembered; a holiday that George Washington had declared back in 1789—but one that wasn’t universally celebrated in Tennessee, perhaps not celebrated at all, and in any case was not a government-approved day off.

Thanks to both journalists and politicians, things were stirring in 1846. By October, it got around that Georgia and South Carolina had designated Thursday, Nov. 5, as a joint Thanksgiving Day. “Why should not the same venerable custom be adopted in Tennessee?” asked an anonymous editor for the Nashville Tennessean. “Have the people of our State have nothing to be thankful for?”

Soon the governor of Kentucky joined suit, calling Nov. 26 Kentucky Thanksgiving. Unlike its deep south relatives, Kentucky’s Thanksgiving would be not on the first Thursday, but the last one. “Will Tennessee be the last of her sister states to adopt it?” asked the Tennessean.

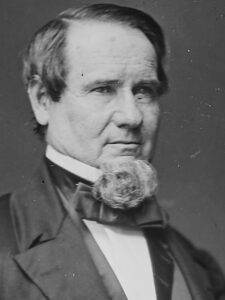

Aaron V. Brown (1795-1859), 11th Governor of Tennessee from 1845 to 1847. (Wikipedia)

Tennessee’s governor, Aaron Venable Brown, was a former Congressman from Giles County, at the southern edge of Middle Tennessee. Brown was a staunch supporter of the war in Mexico, and called for 30,000 volunteers from Tennessee to fight. But as the costly invasion lost support with the people, as around 14,000 Americans lost their lives. Brown lost popularity, too, and he perhaps needed a distraction. Under some pressure, he declared that Tennessee would join the Thanksgiving states.

On Nov. 24, 1846, Gov. Brown signed his name to a somewhat murky statement in Nashville: “Whereas it has been an ancient custom in most of the States of this Union to set apart, at stated periods, some day on which all the people thereof, might in common unite in prayer and supplication to the Author of all our blessings both temporal and spiritual ….

“Now, therefore, I, Aaron V. Brown … hereby designate and set apart the last Sabbath of the present year, to be observed by all the good people of this state, whose heart may incline them thereto, as a day of thanksgiving, humiliation, and prayer.”

In a short piece remarking that the governor of Missouri had just declared Thursday, Nov. 25, 1847 to be an official Thanksgiving, the Knoxville Register made a bit of fun of Tennessee’s own governor: “Last year [1846], Gov. A.V. Brown selected one of the Sundays in November, if we remember aright, and in some manner had ‘Fast Day’ and ‘Thanksgiving’ both mixed up in his proclamation. The Governor meant right enough, and doubtless thought it was all correct; but he committed a blunder nonetheless. Sunday is the best day in the week, in its place, but it is not the best for all purposes, and is not quite as appropriate as Thursday, for feasting and rejoicing among friends, for cracking nuts and jokes—to say nothing of shooting turkeys—without which, and many other things too numerous to talk about, the occasion, to one who knows what a good old-fashioned Thanksgiving Day is, would just be just no Thanksgiving at all.”

It’s the earliest reference I’ve seen that someone in Knoxville had a personal memory of a “good old-fashioned Thanksgiving Day,” even if the Moses’ memories would have been from New England.

On Dec. 23, 1846, soon after Brown’s proclamation and just before the designated day, Dec. 27, the Register printed, in a prominent column on the masthead page, just under the latest news of the war in Mexico. Headlined “Gen. Washington’s First Thanksgiving Proclamation,” it was President George Washington’s own October, 1789 proclamation, signed in New York not long after his original inauguration, that Thursday, Nov. 26, 1789, should be a formal “Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer … to be devoted by the people of these States, to the service of the great and glorious Being who is the beneficent author of all the good that was, is, and shall be.”

It included some language that might cause problems for a president today: “that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech Him to pardon our national and other transgressions.”

Do modern presidents ever mention national transgressions? Before they’re facing indictment, I mean?

Washington didn’t mention any pilgrims, or anything about dinner, and that proclamation may have been related to an old patriotic holiday, Evacuation Day; the day before, Nov. 25, was the sixth anniversary of the departure of British soldiers from New York.

The Moses brothers may have printed Washington’s proclamation, then more than half a century old, just to remind Tennesseans who might be unfamiliar with the concept that Thanksgiving is supposed to be in November, not December, and supposed to be on a Thursday, not a Sunday. But it had also been recently printed in the New York Journal of Commerce, with the line, “We presume few people have read his beautiful and appropriate Proclamation.”

In early 1847, the Knoxville Register quoted a Nashville report, signed only by the initial “W,” that “Yesterday [Dec. 27, 1846] was observed by the churches as Thanksgiving day, being the first ever appointed in this State, I believe. The services at all the churches were appropriate to the occasion. By the by, I think it would be best to have some other day than Sunday for Thanksgiving. It should be on Thursday. However, for a beginning, I suppose Sunday will do.”

***

The Register kept pushing for it, publishing a hopeful headline in early November, 1847: “A National Thanksgiving.”

It was not exactly national yet. So far, according to contemporary reports, only New York, Missouri, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts had declared Thanksgiving to be an official state holiday.

We’re accustomed to planning our Thanksgivings in advance, but the first celebrants didn’t have that luxury. “The Governor has set apart the 25th day of this month as a day of Thanksgiving and Prayer,” reported the Knoxville Register—on the 23rd. “Most of the States of the Union have selected the same day. We hope the Governor’s suggestions will be carried into effect.”

So, we’re going to celebrate Thanksgiving, and it’s day after tomorrow. They barely had time to thaw a turkey.

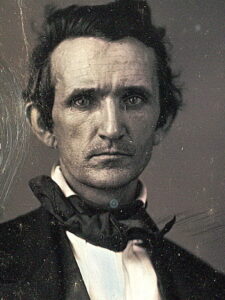

Neill S. Brown (1810-1886), 12th Tennessee Governor from 1847 to 1849. (Wikipedia)

That was a different governor, by the way, in fact a different Gov. Brown: inaugurated only a month before, Neill S. Brown was a Whig, a former elector for Knoxville’s presidential candidate Hugh Lawson White and later an associate of Parson Brownlow. Also from Giles County, he was a strong opponent of the Mexican War, and popular here as a supporter for a state school for the deaf.

The next day, with a headline, “Thanksgiving Day,” the Register politely reminded us, “It will be recollected that to-morrow (Thursday) is the day set apart by the Governor, to be observed as a day of public Thanksgiving throughout the State. Appropriate religious services, we understand, will be held at several of the Churches in this place, on Thursday morning.”

It’s not obvious that it was a major success. It’s harder to find mentions of Thanksgiving in the late 1840s and early 1850s. In 1849, the Moses brothers had given up the Register to editors who seemed less enthusiastic about launching holidays in this rough-edged town still hoping for a railroad.

Another governor, William Trousdale, of Sumner County, went through the motions again, “in concurrence with several of our sister states,” with a proclamation for Nov. 29, 1849.

In 1851, Parson W.G. Brownlow’s Knoxville Whig briefly mentioned Thanksgiving and approved of it, albeit in a paragraph buried in a political essay: “Thursday was Thanksgiving-day, appointed by the Governor of this State, [presumably new Gov. William Campbell, of Sumner County, who was, like Brownlow, a Unionist Whig] and also by the Governors of 25 [of 31] other States. All the business houses were closed, and Divine services were performed in the various churches. This all looks well, and seems appropriate, morally, socially, and politically, in a Christian people. We should acknowledge with humility our lasting obligations to the Supreme Ruler of the Universe, for the blessings of civil and religious liberty, and for food and raiment; but it did seem to me there was a little too much Liquor drank on that day. True, it rained all day, and was cold, and otherwise disagreeable, which formed a sort of excuse for drinking!”

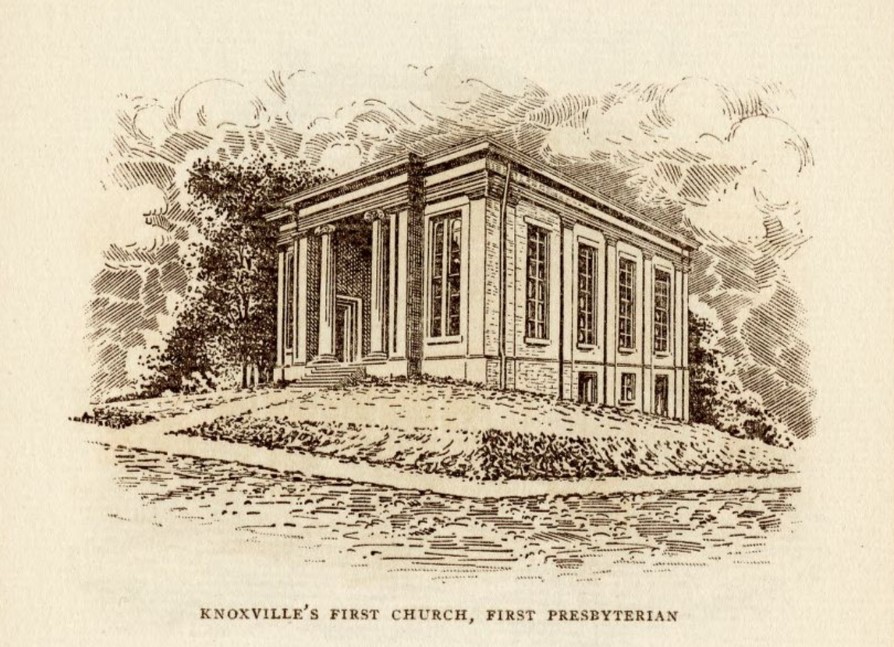

In 1855, another governor, the 47-year-old tailor from Greeneville named Andrew Johnson, made a proclamation that Thanksgiving be observed on Dec. 6. It may have been the first official celebration of the holiday in Tennessee in a few years. In any case, perhaps partly because that governor later became president, it seems to be better remembered than the previous ones. And for perhaps the first time, it was celebrated in a concentrated public way, with a “Divine Service” held at First Presbyterian Church. It was an ecumenical service—in fact, the pastor leading it was Episcopal priest Thomas Humes, much later to be president of the University of Tennessee. It’s likely that it was held in the Presbyterian church because it was a brand new and capacious building, a neoclassical marble-faced structure at the corner of State and Church. (The current structure there replaced it in 1902 in a comparable style, and reputedly with some of the same foundation stones.)

The original First Presbyterian Church building, from “Keeping the Faith: A History of East Tennessee Bank,” 1924. (McClung Historical Collection.)

“We presume our citizens will properly observe the day, and as is customary allow a suspension of business on the occasion,” said the Register. The line “as is customary” seems to suggest Knoxvillians were familiar with the holiday, even if details before that era are elusive.

One thing that was not yet customary was the date. The following year, Tennessee shifted the holiday into November, but it remained a week later than the holiday as celebrated in most other states.

The year that Thanksgiving became a national, federal holiday, was probably the most famous Thanksgiving in Knoxville history. When Abraham Lincoln declared it to be a national holiday, on Nov. 26, 1863, Knoxville shared the national news, because the city was under siege by more than 17,000 Confederates, some of whom were manning the big guns on the cliffs across the river that allowed them to bombard the city’s western forts, along with the university. Much-admired young Gen. Sanders had died of a sniper wound a week before. Few Knoxvillians could have celebrated the feast, because food was in short supply. Still, Gen. Burnside complied with his commander in chief’s holiday directive, issuing General Field Order Number 32, which instructed his embattled soldiers to observe Thanksgiving. As the late historian Dr. Digby Seymour remarked, Knoxville’s defenders received “a full ration of bullets but only a half-ration of bread.”

The short but horrific Battle of Fort Sanders came three days after Thanksgiving, a Confederate bloodbath on the muddy ramparts that ended the siege.

The Civil War and its losses stunned Knoxville and made it forget most holidays for a while. But by the late 1860s, the city was growing rapidly, enjoying a cultural renaissance, culturally livelier than it had been before, afterward.

It’s typical of 19th-century Knoxville that the first handy evidence that we were eating a big Thanksgiving Dinner, and not just praying at a religious service, on the big holiday, comes from an exotic source.

One of the first stores to advertise ingredients for Thanksgiving recipes was a unique Market Square store with an Asian persona. Advertised with an eye-catching Chinese sculpture out front, Tea Hong carried imported teas, coffee, and other goods from overseas. Despite its Eastern image, it was actually run by a colorful European immigrant named Victor Hugo Sturm. The resourceful Mr. Sturm was said to be Jewish, but he also claimed to be a godson of French novelist Victor Hugo; whether he was from Germany or Portugal, as different sources have it, is unclear.

On Nov. 14, 1869, Sturm advertised “every thing that is rare and choice for your thanksgiving dinner; such as Celery, Grapes, Mince Meat, Oysters, Sardines, New Figs, New Raisins, all kinds of Jelleys and Preserves, Almonds and other kinds of Nuts, all kinds of Cheese, all kinds of Crackers, all kinds of French Fruits, in their own juice, English Pickles and Sauces, in great variety, Cranberries, choice Butter, the finest Potatoes in the world, New Hams, New Beef, the choicest Family Hams, and all other articles that may be needed.”

It may be the earliest list of ingredients for a Knoxville Thanksgiving meal. Who needs turkey?

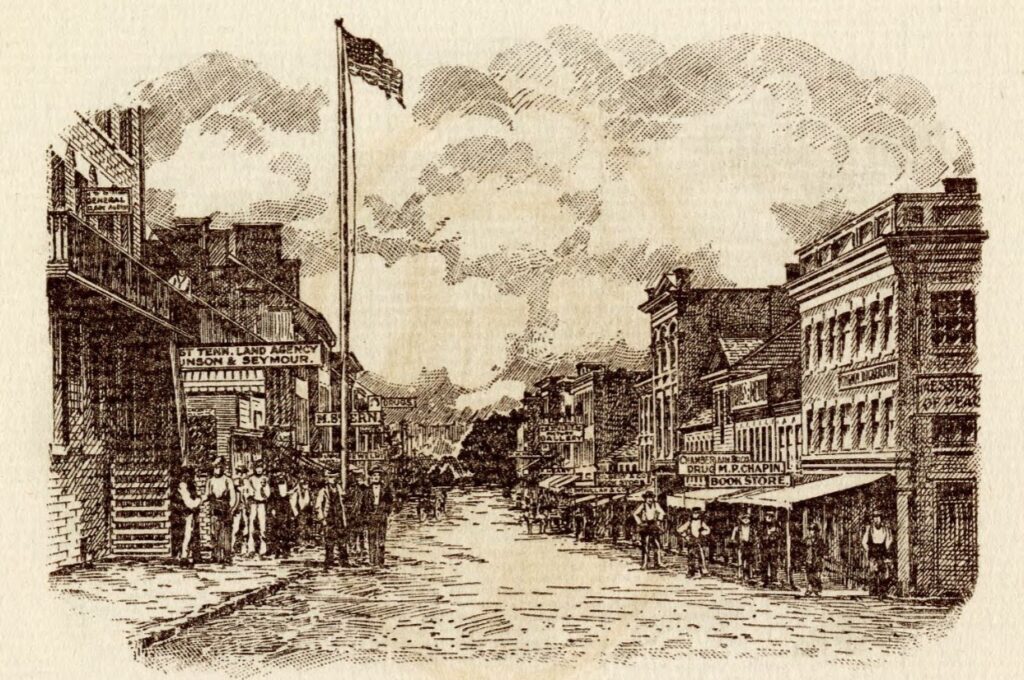

Knoxville in the 1860s, from “Keeping the Faith: A History of East Tennessee Bank,” 1924. (McClung Historical Collection.)

Several years later, in 1900, the only book ever titled the Knoxville Cookbook, recommended a “Thanksgiving Dinner Menu.”

It opens with a quote from the 17th-century British poet Abraham Cowley: “With a few friends and a few dishes dine, And much of mirth and moderate wine.”

The quote is appropriate to this early Knoxville Thanksgiving—all, that is, but the “moderate” part.

It opens with “Oysters Served in Square Blocks of Ice,” and continues with lemon and celery. Then Puree of Asparagus with Whipped Cream.” Followed by sherry, of course. Then baked fish, cucumber salad, and another wine, Sauternes. Then some “Chicken Souffle in Cases,” followed by still another wine, Claret. Then, finally something familiar: “Roast Turkey, Stuffed with Chestnuts, Cranberry Sauce.” Followed with macaroni and corn. Then, assuming you’re still craving a drink, a course of Roman Punch—which, if you’re unfamiliar, is a pagan concoction something like a champagne mimosa, complicated with additional fruit juices, rum and brandy.

Then, assuming you didn’t get enough turkey, some roast quail and celery salad. And, of course, Champagne.

For dessert, “Individual Ices,” cake, coffee, and Crème de Menthe.

So, at the end of the century that spawned our Thanksgiving as a day of prayer in church, we were recommended to enjoy six different kinds of wine and liquor with our enormous meal.

If you have the wherewithal to try that recommendation in its entirety, please get in touch. You may need to sober up first.

Happy Thanksgiving, whatever that means to you.

Jack Neely, November 2023

Leave a reply