OPERA’S DEBUT IN KNOXVILLE

Both locals and newcomers tend to jump to the same conclusion: that Knoxville, whose founders were surely country-music or gospel fans if they knew anything about music at all, decided at some point—in recent years, of course—to put on airs, to imitate Atlanta perhaps, and get us up an opera company. The assumption is that opera, with its context of Nordic demigods and overdressed princes, remains foreign and contrary to our Appalachian character. Even if we’ve all known a few Falstaffs in our time.

As is often the case, reality surprises. In fact, the record would suggest that opera was here in downtown Knoxville, and a very big deal, before any other legitimate public entertainments. The sudden celebration of European opera in the years just after the Civil War was arguably the beginning of our modern habit of buying tickets to see jazz or rock shows. And there’s at least anecdotal evidence that opera played a specific role in sparking a local interest in country music.

Granted, early Knoxville is a shady character in some ways, and it’s hard to find much evidence that the struggling little town had any very coherent culture, high or low. During the city’s first several decades, before the Civil War, there were few advertised public performances of any sort, outside of the Presbyterian and Methodist churches and an occasional Whig rally.

If you skip religious or patriotic events, you could probably count the known musical performances in Knoxville before 1865 on your fingers and toes.

However: when we talk about the history of opera, it’s hard not to mention a couple of things that made Knoxville exceptional in that regard. One was an extraordinary encounter with a creative fellow of international stature, a “prince of bohemians,” who was associated with opera and spent some significant time in Knoxville during those spartan years.

John Howard Payne (1791-1852) (Wikipedia)

Born in New York, John Howard Payne was an actor and playwright who spent most of his career on and around the London stage. He became best known for an 1822 operetta called Clari, the Maid of Milan, moreover for the show’s best-known aria, the melancholy “Home, Sweet Home.” You know it; it’s even in cartoons, with its distinctive line, “be it ever so humble.” Payne wasn’t here to perform. His fascination with the Cherokee brought him to spend some time with the original Cherokee Nation during its final years in Georgia. Arrested in Tennessee by the Georgia State Guard in 1835, Payne escaped across the mountains to Knoxville, home of the open-minded Knoxville Register, which published his harrowing narrative of his treatment, and about the government’s abuse of the Cherokee.

The famous playwright’s ordeal, as related in the Register, got the attention of readers across America; even John Quincy Adams in Massachusetts remarked on it. Payne was here for several days. He’s not known to have done any singing or acting in this pragmatic little town where the only stages were in a couple of churches and the courthouse.

His “Home Sweet Home” would be a favorite at multiple shows during Knoxville’s first opera era, decades later, often performed at the end of a show—perhaps a polite suggestion that the audience just go on home.

***

Rare as they are, published anecdotes about opera and opera people in London or New York appear in early local newspapers, so early Knoxvillians had at least heard of opera. It’s likely that several of Knoxville’s first citizens who had lived in Boston or Philadelphia had experienced an opera or something like it in their past. But before the arrival of railroads in the 1850s, this tiny, leftover frontier town suggested little pretention or aspiration to urban culture.

In March, 1836, just a few months after Payne’s visit, the same Register ran an ad for a New York music supplier called Atwill’s Music Saloon, describing “selections from Rossini’s Operas for Two Flutes.”

Although it’s just an ad for a faraway retailer, it’s the first suggestion that there might have been a passing interest in operatic music in this leftover frontier town of about 2,000 people—and the first local appearance of the name of Gioachino Rossini, a 44-year-old Italian composer who would loom large in Knoxville’s 21st-century history as the honoree of a major festival. It’s one of the first times any opera composer’s name appeared in local papers.

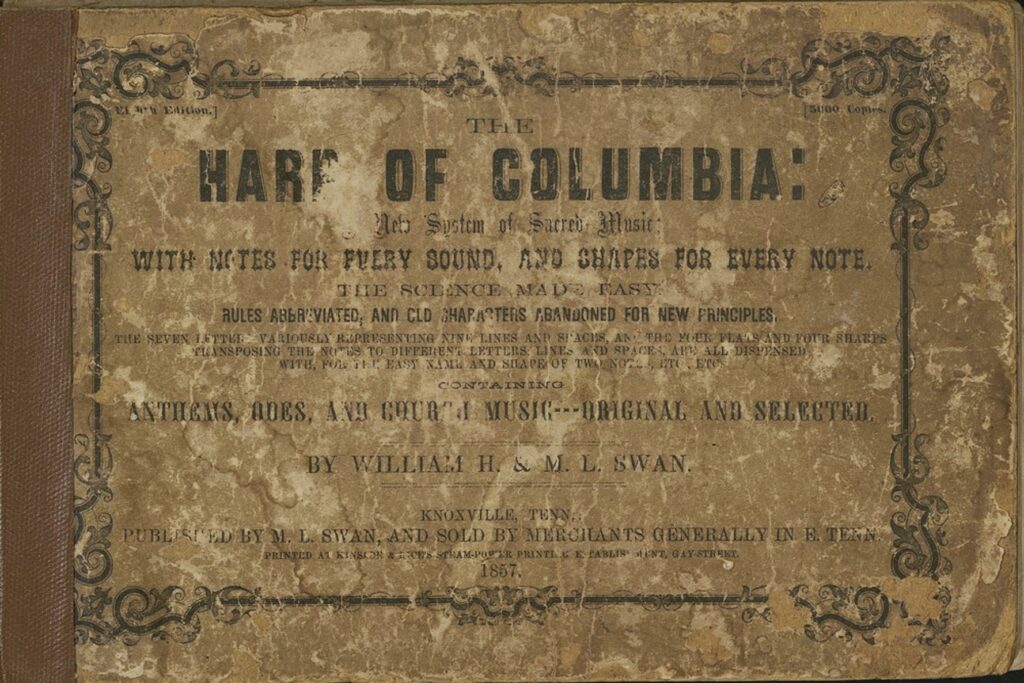

The publication of several shape-note guidebooks with sheet music in the 1840s and later suggests that Knoxville had a reputation for that Sacred Harp singing—which is very different from opera, but demands vocal discipline and some understanding of how harmony works.

By June, 1848, a “Philharmonic Concert” given by a “Philharmonic Society” in Knoxville was reportedly well-attended—though a short writeup mentions nothing about the venue, the program, or the performers, offering us little clue of what it was like. But that same phrase would pop up almost 20 years later, in a much more significant context.

One of Knoxville’s first heralded concerts sounds more like a sideshow. In June, 1849, an ad goes “GEN. TOM THUMB: This celebrated English dwarf proposes to give a grand vocal concert this evening at the court-house. We hope the general will be liberally patronized, as he is himself a great curiosity, and will, no doubt, give a very entertaining concert.”

The famous Connecticut-born Tom Thumb was not English, though by then, when he was only 11, he had already toured in England and met Queen Victoria. Details are scant. But is it possible that the celebrity, who was not much more than two feet tall, performed Knoxville’s first advertised vocal concert?

The arrival of railroads supercharged the old town and its cultural aspirations. An organization called the East Tennessee Musical Association, made up of 24 men, materialized by 1855, with the stated intention of organizing public concerts. Among them were New Hampshire native George Cooke, who was then the president of the university, and Massachusetts-born Alvin Barton, who would be a key figure in opera development in years to come.

A rare “Concert” by Blakely’s Orchestral Chorus Company, described as “two ladies and three gentlemen from the Boston and New York Academies of Music,” was an apparent success at the local Odd Fellows Hall in March, 1855. The association wrote an open letter of praise: “We part with you as artists and friends, assuring that wherever you go, our best wishes are with you.” The Knoxville group’s letter was quoted to promote Blakely’s Nashville appearance.

An unsigned editorial in the Knoxville Register in early 1857 asked, “what has become of the East Tenn. Musical Association and her Concerts? Let us have something occasionally to relieve the monotony of everyday life.”

A list of its members, which included a few Swiss immigrants, but also both hardcore Unionists and Secessionists—including William G. Swan, the future Confederate Congressman–may suggest why it came apart. Cooke resigned from the university amid accusations that he was an abolitionist.

Meanwhile, a Professor J.W. Erdman, from Indiana, showed up in town, advertising himself as a teacher of piano and guitar, he taught at the East Tenn. Female Institute, a respected school for young women. He presented a series of public vocal recitals, one of them described as a “delightful and refreshing entertainment.” But the professor seems to disappear soon after that.

Something of semi-serious intent arrived at the Lamar House hotel in 1858: a quartet called the “Sight-Singing Concert Troupe,” including R.F. Beal, the “lion bass,” as well as a tenor and two sopranos. According to a rare witness, “the audience, among whom were some of our well-known amateur musicians, were delighted with the performances.” Beal was an author in the sight-singing field, and may have been here to sell some books.

***

However, it was not until about two years after the Civil War that Knoxville started singing, and singing in a trained and practiced way, and drawing audiences to hear it. This sustained interest in vocal music emerged almost suddenly, much of it prompted by the arrival of one extraordinary newcomer. As Knoxville grew rapidly with railroad-fueled industry, waves of immigration, especially from several German-speaking principalities, refugees from political chaos as a result of the Revolutions of 1848, were changing the culture of East Tennessee, sometimes radically.

Originally from Leipzig, home of Bach and Mendelssohn, Gustavus Knabe was in his 40s when he first strolled down Gay Street. He was, in fact, a former member of Mendelssohn’s orchestra, and had reportedly been friends with Robert and Clara Schumann and a passing acquaintance of the young Richard Wagner. He crossed the ocean and gravitated to Wartburg, founded as a New World refuge for German immigrants. He then roamed around the region some, living in Maryville, Athens, and Cleveland, where he enlisted in the Union Army, leading a brass band for an Ohio regiment. Knabe (his German name is pronounced with three syllables, something like “Kanobba”) played several instruments, and was related to the Knabe Piano family of Baltimore, but he was an expert on the French horn.

He landed in Knoxville around 1864, perhaps attracted by a number of other talented Germans here.

In Knoxville, in 1867, when not much seemed to be going well in the war-ravaged city except for the introduction of baseball, Knabe founded a group of musicians and singers he called the Philharmonic Society.

On a Friday evening just before Christmas, in an old bank building on Main Avenue, Knabe convened this new musical club, “invited from all the choirs in the city,” to create something remarkable.

It was barely two months before the group put on its first concert. “A large and appreciative audience assembled the old Methodist church last night, to listen to the concert of the Philharmonic Society,” reported the Daily Press & Herald. “Of the concert we can say nothing less than it was a splendid success. The managers, with rare judgment, arranged the program so that the exhibition was just long enough to gratify the lovers of good music without becoming tedious to any.” That’s the essential challenge, then as now.

Included in the show was the overture to Martha, presumably by Flotow; “Invitation a la Valse,” perhaps by Von Weber; the wrenching “Miserere,” from Trovatore, by Verdi—it had premiered in Rome only 15 years earlier—involving an organ, piano, and Knabe’s French horn; then a “barcarolle” as a vocal duet (it could have come from any of several operas); and the famous “Fantasie,” a complex piano solo adapted from Donizetti’s Don Pasquale, an opera then 25 years old.

In 1868, Knoxville had never seen a country-music concert or a football game; it didn’t yet have a public library, public transit, or a sewer system. But it had opera—or, at least, arias from operas.

Apparently encouraged by the popular response, the following month Knabe announced the formal aspirations of the Philharmonic Society: “To encourage a taste for good music in the community—to afford opportunities for practice and an advanced school, as it were, for the musicians of Knoxville—also to afford a pleasant and profitable amusement for both musicians and their friends.” They rented a room big enough to hold 100, and a piano. They would charge for concerts, but also asked for donations. It sounds as if Knabe, the conductor, was paid something for his services, making him perhaps Knoxville’s first professional musician—but the musicians were expected to do it for the love of music. They would practice weekly, and give a public concert every six to eight weeks. Knabe was a composer, himself, and most of the early programs include one or two of his own pieces, mainly instrumentals. He became most famous for a funeral march.

By April, 1868, the Daily Press and Messenger was so impressed by this sudden surge of vocal talent that it declared, “No city of its proportions has more musical genius than Knoxville.”

A reporter made his way into the Main Avenue headquarters to listen. “We strayed into the Philharmonic Hall, on Friday night last; we found Professor Knabe standing in the center of a semicircle of fifty singers, gesticulating most vehemently, and sometimes furiously. We asked a friend what he meant. He replied, ‘he is marking time.’ We were quite delighted with the music, and became satisfied that all that was necessary to make Knoxville quite celebrated for its musical talent was a little concentration and organization of the individual genius of the different members of the society. This Professor Knabe is trying to do.”

The concert of April, 1868, included a solo and chorus from Verdi’s Ernani, an 1844 opera. Giuseppi Verdi, who was 54 at the time his work was being performed in Knoxville, was still very active; some of his best-known operas, like Aida, Otello, and Falstaff, were still in the future.

That concert also included Sue Barton performing “The Fairy Queen,” likely the Henry Purcell composition from an operatic work: “Of course it was applauded,” noted the Press & Herald, “and of course it was encored, for whoever heard her birdlike voice that did not long to hear it again?”

They closed that one with a flute solo of “Home, Sweet Home,” the song written by John Howard Payne. It’s likely that no one at the show remembered the operatic songwriter had ever spent a dramatic week in Knoxville. Payne had died years before. Most of the people who lived in Knoxville were newcomers.

But the old song had enjoyed a surge of popularity during the Civil War, sung by sentimental soldiers on both sides.

The Society’s members became local celebrities. John Scherf, the German immigrant who was the “Prince of Caterers” at the Lamar House, hosted an oyster party for the Society, which by then numbered about 60. On another occasion, all the singers were invited en masse to the estate of coal tycoon E.J. Sanford for a party of ice cream and strawberries. Of the Society, several pianists and violinists were mentioned—and Mrs. Trowbridge, a Miss Craigmiles, a Miss Mabry (perhaps Isabelle, daughter of West Knox County’s George Mabry), and a Miss Cowan. But among Knoxville’s early singing stars, one towered above the rest, a woman routinely referred to as “Mrs. Barton.”

Then in her mid-20s, Sue Boyd Barton was a Knoxville native—born in Blount Mansion, in fact—who had already lived a life worthy of a Verdi plot. Daughter of a judge and Knoxville mayor, she was a cousin of Confederate spy Belle Boyd, who has sought refuge with Sue’s family after some misadventures along the Virginia front to evade imprisonment. They apparently became friends. But later the same year, Sue fell for a handsome young Union brigadier general named William Sanders, who was mortally wounded defending Knoxville from the Confederate siege. Sue later married a Unionist merchant, Massachusetts-born Alvin Barton, but for the rest of her life she treasured a keepsake Sanders had left her—perhaps as he lay dying at the Lamar House—the uniform epaulet he had worn as a colonel.

Some called her “Knoxville’s Jenny Lind.” An early 1868 Knoxville Press & Messenger article remarked in a concert review, “Mrs. Barton’s singing was what it has always been—the ne plus ultra of vocal music; nothing can surpass it.”

The Society elected officers. The first president was Alvin Barton, the Massachusetts-born retail executive who’d been promoting cultural education since before the war. He sometimes sang, himself, and may have been obliged to, being married to Knoxville’s favorite soprano. What he thought of his wife’s preoccupation with her lost brigadier general is unrecorded.

Vice president was Dr. John Mason Boyd—the celebrated gynecological surgeon whose name would later be heralded on the porte-cochere of the courthouse.

Most of the operatic singing was by locals, and mostly performed in local churches. The German-immigrant group known as Turn Verein raised the bar, opening a public hall in what had previously been a fraternal lodge on Main Street, near Prince (today, somewhere near the main entrance to the City County Building). In those politically toxic days, the new venue had a strict no-politics rule. It was apparently not quite finished in June, 1869, when it hosted, for three nights, the Great Western Buffo Opera Troupe, apparently a traveling company promising “Operas, Burlesques, Extravaganzas, Farces, Pantomimes, and Ethiopian Minstrelsy.”

In October, 1869, a more polished Turner Hall welcomed the John Templeton Opera Troupe, who performed there over a period of several nights in May, 1869, a production of Camille as well as some operettas.

Named not for the famous English tenor who was still alive then but for a New York singer, the troupe starred Templeton’s wife, known as Alice Vane, but the other performers and the nature of the opera isn’t obvious in news accounts—but it’s likely that their Camille was a version of Verdi’s La Traviata, based on an Alexandre Dumas novel. That opera had been making the rounds since 1853. All we know is that the hall for what may have been the first opera ever presented in Knoxville was “crowded with a fashionable audience.”

The music itself was always important, and exhilarating to some listeners. But the “fashionable audiences” sometimes impress writers more than the performances. It seemed important to them to let the world know, in those rough-edged days when all saloons had spittoons and gunfights in the street were common, that Knoxville respected opera. Part of the appeal of opera was social, and valuable in part to improve Knoxville’s image.

Turner Hall occasionally hosted Philharmonic Society concerts, as in June, 1870, when a series of selections including Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots highlighted the singing talents of Sue Boyd Barton and a few others. A Mrs. Craigmiles, from Cleveland, Tenn.—one of the few members who didn’t live within walking distance—sang the “Fantasie” from Rossini’s William Tell.

Many of these singers seemed dedicated to their craft. In an era when a good marriage was regarded as elemental to happiness and success, several of Knoxville’s first generation of singers never married; of those who did, few had children. They were always available for a rehearsal.

The sudden popularity of opera drove a frenzy of theater-building. At about the same time Turner’s was hosting its first opera in late 1869, J.B. Hoxsie, a hustling New Jersey-born railroad man and oven merchant since before the war, opened his Hoxsie’s Hall, “a new temple of art,” on the second floor of a Gay Street building in November, 1869. It appears it was about where the Krutch Park extension is today. Its first event was a concert of Knabe’s Philharmonic Society. Later, Hoxsie’s reportedly hosted an obscure opera called The Stranger. The Templeton Opera tried Hoxsie’s Hall for a few nights in November, 1870. A high point came in February, 1871, when Hoxsie’s hosted the Adelaide Phillipps Concert Co., featuring that popular contralto from England, in February, 1871. Phillipps was probably the best-known performer of any sort in Knoxville history up to that time (unless we count Mr. Thumb, with whom Phillipps had in fact performed, herself, early in her career). In her company were composer-pianist Edward Hoffman and baritone Jules D’Hasler—who had recently escaped war-besieged Paris in a balloon.

Hoxsie’s lasted only about nine years, but its building later became the location of McArthur’s Music Hall, an elaborate piano dealership that hosted scores of musical events for many years to come.

Another building, the mundane-sounding Board of Trade Hall, sometimes hosted Philharmonic Society concerts, too, as in early 1872, when their program included sung pieces by Verdi, Rossini, and von Weber—as well as compositions by Knabe, himself. He was never shy about inserting his own work into any program.

In 1871, President Ulysses Grant appointed Knabe consul to Ghent, an unusual honor. Knabe declined the post, choosing to stay in Knoxville. Things were just getting exciting. By that time, he was teaching some at the university. In fact, one of his first homes was in the “East Building” up on College Hill. At the time, East Tennessee University, under the leadership of author and former Episcopal priest Thomas Humes, was still known for its liberal-arts emphasis, though that would soon shift, as federal funding for vocational study became available.

Julius Ochs (1826-1888)

One of Knabe’s fellow German-refugee-immigrant peers in Knoxville was Julius Ochs, a judge, energetic merchant, and lay rabbi who cofounded Temple Beth-El, but best remembered to history as the father of Adolph Ochs, influential future publisher of the New York Times. Ochs and his wife, Emma Levy Ochs, had lived here before the war; they returned in 1864, about the same time Knabe arrived. Knabe and the elder Ochs both served on a local German Relief committee, to help those injured or displaced by the Franco-Prussian War.

Julius Ochs was also a talented musician, and in the postwar period reportedly created an opera with an Old Testament theme. Little detail of that work remains. However, he and Knabe worked together on a pro-German musical farce called Napoleon and William. Ochs wrote the play and performed a role as a Prussian officer; Knabe wrote and directed the music. It played to a “select and gratified audience” at Turner Hall. It was declared to be “one of the most laughable performances that has ever been placed upon a Knoxville stage.” (It wouldn’t have been popular with everybody; there were some French sympathizers in town, including one university professor, Frederic Esperandieu, who actually returned to Europe to help the French forces as a medic.)

***

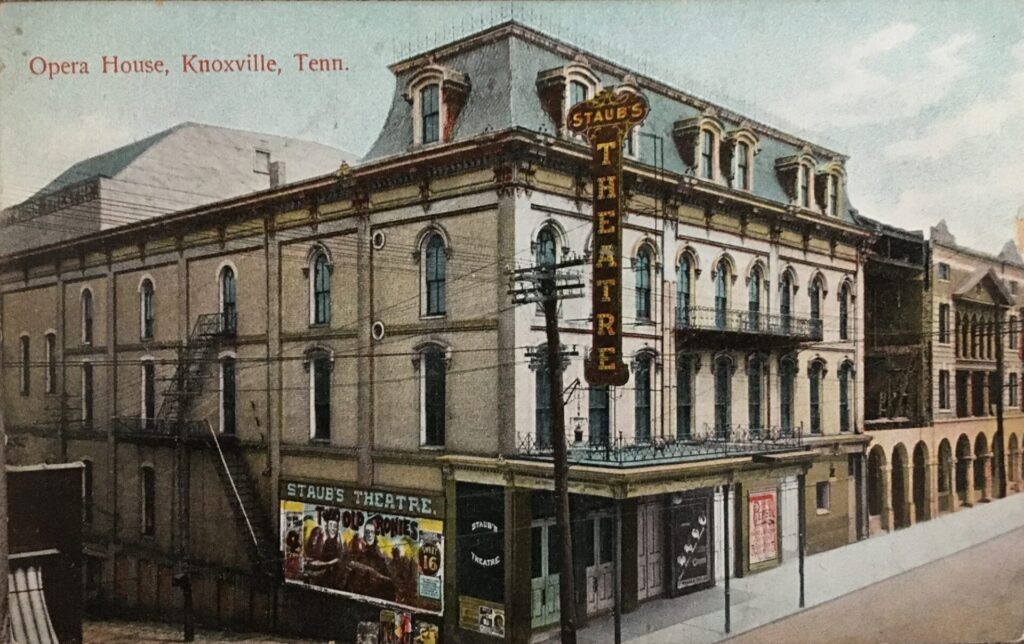

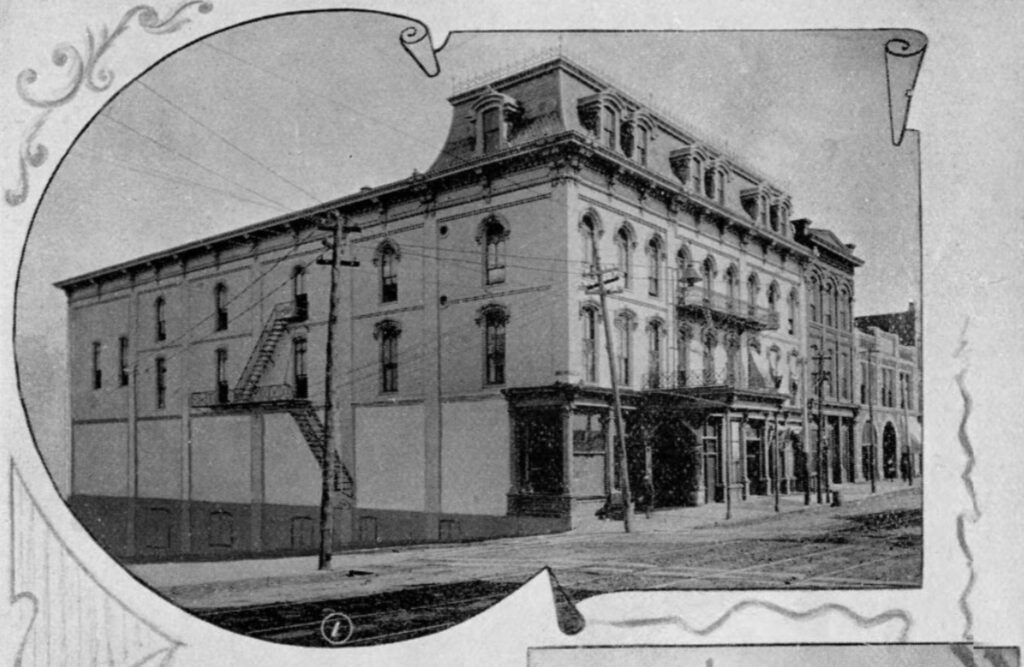

All that was happening before Knoxville had anything that city folks would call a theater. German-speaking Swiss immigrant Peter Staub arrived in town not long after Knabe, nursing the humiliation of the failure of an attempt to found a Swiss community in the Cumberlands. Impressed with Knoxville’s sudden interest in the performing arts—and the inadequacy of the city’s theaters—he built Staub’s Opera House at the southeast corner of Gay and Cumberland, an elaborate European-style opera-house with multiple balconies, designed in the new Second Empire style, all the rage in Paris, a city Staub knew well. Its interior decor celebrated the “Alpine splendor” of his beloved Switzerland. His stated goal was to build a theater that would please, “especially, those who love opera and drama” in a venue so grand that it would tempt “first-rate troupes” to the city that until recently had little reputation for performing arts. With seating for over 1,000, with a dedicated section for African American patrons, it got notices across the South, reported to be “the largest and finest edifice of its kind in the state.” It was the most impressive building in town.

Perhaps in gratitude, Knoxville elected Staub mayor, twice.

As the theater was under construction, Staub became president of the Philharmonic Society. He reserved a third-floor hall for the use of Knabe and his impressive singing troupe. It was just in time, because the state Supreme Court had just taken over their old hall, on Main.

Peter Staub (1827-1904)

Staub’s first production was William Tell—not the Rossini opera, but the 1825 play. It was presumably non-musical, though it opened with an “Overture,” performed by the Hodgson Orchestra, led by English-born musician Herbert Hodgson, musical brother of writer Frances Hodgson Burnett; their immigrant family had moved here about the same time Knabe did. The most complicated and expensive of art forms at the time, full-fledged opera, with orchestra, chorus, conductors and stage managers, was never frequent at Staub’s. More typical were simple concerts or vocal recitals; comic operettas, which might strike us more like Broadway-style musicals; variety acts that would become known as vaudeville, just evolving at the time; and lectures, by nationally popular writers George Washington Cable, James Whitcomb Riley, and even Frederick Douglass. But for more than half a century, Staub’s would be Knoxville’s grand venue for music, especially singing, and apparently did host several full operas.

In its inaugural season, in January, 1873, Staub’s welcomed Ole Bull, the Norwegian violinist who was one of the best known instrumentalists in the world, having been associated with Robert Schumann, Edvard Grieg, and Franz Liszt. In Knoxville he accompanied opera singers, including soprano Graziella Ridgway and a baritone known as Signor Ferranti. They sang, among other pieces, selections from Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Aware that he was performing in a recently opened theater, Bull left Staub a written commendation: “It gives me great pleasure to recommend your Opera House to any first-class Company, as in every way perfect in all its arrangements and acoustics….”

It was an enviable mark of distinction that may have helped launch Staub’s credibility to such a degree that over the next 25 years, the theater attracted some of the world’s greatest singing talent, but still celebrated the best of the local.

A few weeks later, a Philharmonic concert featured 10 singers, and again the newspapers singled out one: “Mrs. Barton, of course, electrified the audience with her magnificent voice and perfect culture,” reported the Daily Press & Herald of her interpretation of an aria from Donizetti’s Lucretia Borgia. “Her singing was exquisite.”

The word choice is worth noting. She electrified the audience many years before the theater itself, or anything else in town, was literally electrified.

The Chronicle quoted an item in The Record, apparently a newspaper in another state:

“Good music—so earnestly desired and so seldom found—has in the city of Knoxville many warm supporters … we rejoice to state that good music is better sustained in Knoxville than in almost any city in the South. The Philharmonic Society, numbering about 60 active members, under the leadership of Professor Knabe, has well rendered to appreciative audiences some of the most difficult productions in the whole repertory of song…. Through many discouragements and years of toil he has lived to see his favorite notions of music adopted, and instead of the sentimental love ditties of modern days, there is now a demand for the grand harmonies of the old masters.”

The old masters were not all that old, by the way: Donizetti had died only 25 years earlier. Verdi was pushing 60, but still had some of his best-known work ahead of him.

Some of the Philharmonic Society’s shows raised money to help alleviate major disasters. In October, 1871, the Philharmonic brought together 40 musicians at Turner Hall to perform a Grand Concert for the “Relief of Chicago.” It was just days after the Great Chicago Fire killed 300. It was a mostly operatic concert including pieces by Rossini, Donizetti, Mozart, Weber, Hoffmann, and Meyerbeer. George Pullman, the railroad-car magnate who was heading up Chicago’s relief effort, sent a personal letter to Knoxville’s Philharmonic Society thanking them for the assist: $152, the equivalent of several thousand today. Another benefit at Hoxsie’s Hall brought in Hodgson’s Band to raise money for musician Charles Hayes, “fallen invalid to a dreadful disease.” A benefit at Staub’s in October, 1873, included several operatic arias from Donizetti and Verdi, and offered aid to the thousands of victims of yellow fever along the lower Mississippi where 2,000 had died in Memphis alone.

It would appear that Staub’s Opera House witnessed the performances of hundreds of arias before its first opera. It’s hard to nail down when that event happened, but it was no later than September, 1876, when Payson’s English Opera Troupe presented German composer Frederick von Flotow’s popular romantic-comic opera, Martha. With a piano for accompaniment rather than an orchestra, as was common for light operas, Martha received “unbounded applause.” In the audience was Knabe himself, who wrote a letter to the Daily Tribune. “Miss [Rachel] Samuels has a sweet yet powerful voice. Especially does she sing in the higher register with perfect ease and without any overstrained effort. Miss [Adelaide] Randall has a rich and charming contralto voice, and combines the histrionic talent with that of the tragedienne most happily.”

Randall, a Baltimore native sometimes described as a mezzosoprano, had a bit of a career singing on the New York stage, but returned to Knoxville for several more rounds of applause at Staub’s.

The same troupe returned with another performance of the same opera five months later, in February, 1877, this time with New York tenor Alonzo Hatch, who later had a national career as a popular singer.

They drew a bigger crowd on the second appearance, one that seems to have been as impressive to the reviewer as the performance itself was: “one of the most fashionable audiences that we have ever seen in the Opera-house—the very elite of Knoxville were present; and, we may add, the citizens of Knoxville could point with pride to the assembly. The ladies, dressed a la mode, presented a most fascinating appearance. A much-traveled gentleman remarked to us that one might traverse the whole territory of the United States without finding an audience of more culture and refinement. But the Paysons deserved the large house that greeted them….”

Described as “first class” but now obscure, Payson’s seems to be known to history mainly for that 1876-77 American tour.

The same company performed other musical plays on evenings thereafter, including Jacques Offenbach’s one-act comic opera Vertigo (a.k.a. Pepito), which “brought down the house.”

Another traveling opera troupe put on a two-act version of Bellini’s emotional 1831 opera Norma at Staub’s in 1880. A Daily Chronicle reviewer attended the dress rehearsal and seemed flabbergasted by how great it was. “The unutterably grand masterpiece of the old Italian maestro is well rendered, and, in the acting and vocalism, well calculated to improve and delight those whose good fortune it is to be present Friday evening.”

In the 1880s, opera soared, as did Knoxville, which almost tripled in population in that decade. A separate company founded by another German-immigrant family, the Krutzsch Concert Troupe, featured, on piano, Oscar Krutzsch—brother of painter/organist Charles C. Krutch (some family members tolerated an Anglicized spelling), who had a studio in Staub’s Opera House. The troupe sometimes toured regionally with a full range of singers, including soprano Cornelia Crozier, a Philharmonic Society veteran who had reportedly “studied extensively abroad and sang with much spirit and sweetness.” She liked to sing from Verdi’s Ernani, and taught music from her studio on Cumberland Avenue.

Professor E.W. Steen, a professional musician, music scholar, and music dealer from Cincinnati, began spending more and more time in this promising city to the south, bringing his musical family with him, and by 1882, they were performing in local productions. Steen sang tenor in a local production of Edmond Audran’s recent comic opera, La Mascotte, at Staub’s in April, 1882.

Knabe, still a major player, founded the Mozart Club, which produced a 15-piece orchestra, plus a “grand chorus of trained voice,” including Cornelia Crozier. Their debut at Staub’s in November, 1882, was described by the Knoxville Chronicle as “an event in Knoxville’s musical history.” It was the month after the horror of the Mabry-O’Conner gunfight, which left all three prominent combatants dead, that the Mozart Club opened another venue, Mozart Hall, just down the sidewalk from the bloody scene. A variegated second-floor space with multiple rooms, Mozart Hall sounds as if it was more for musicians than for audiences—though it did make room for at least 50 spectators—often with musicians and singers performing for each other in a multi-room complex where in December, 1882, they put on a fun pocket production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s recent hit, Pirates of Penzance.

In January, 1883, a local company put on Audran’s new comic opera, Olivette, at Staub’s. Headlined “A Grand Success,” in the Knoxville Daily Tribune, it starred Marie Lawrence in the title role—her “brilliant” performance reportedly received “storm after storm of applause”—but earning special mention was one Mae Bates. “Miss Bates is also a rising star and won a full share of hearty applause. She is very young and timid, but has a wonderfully sweet voice.” Encouraged to go on the road, the local troupe produced a big show of Olivette in Chattanooga’s James Hall. Again, even though she was not one of the leads, Bates was singled out in the Chattanooga Democrat: she “has a strikingly sympathetic voice that masters the most trying intricacies of trills, bravuras, and extravaganzas with remarkable beauty of expression.”

It’s particularly interesting to see that early notices for Bates, one of a few Knoxville singers who gained some acclaim on the international stages of London and New York—as “Villa Knox.” (The stage name paired her home county with an opera setting, even if it sounds today like a suburban condo development.)

By late 1882, Knoxville was abuzz about the debut of the Festival. Sharing the role of musical director were three of the major drivers of musical performance, including Knabe, E.W. Steen, and Ethelrod W. Crozier, a pianist who had been involved with the Philharmonic, mainly as accompanist, since its beginning.

“The May Festival” would be its simple name, and it included a grandiose ball, an art exhibition, and a nonviolent version of a jousting tournament—but it was mainly a celebration of opera. Later articulations would be called “The Music Festival.” The scope of it, and the quality of the featured performers, varied by the year, but can still astonish opera scholars.

It was a spring festival, usually lasting four days. That first year featured a production of Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, Planquette’s Les Cloche de Corneville, Flotow’s Martha—and, yes, Pirates of Penzance. Its star was the 17-year-old Fay Templeton, the soon to be famous actor, singer, and songwriter, early in a career that would bloom on Broadway.

Several of these operas and operettas presented at the festival were new works—in fact, opera composer Plaquette was still in his early 30s. Much of it took place at Staub’s, but with a deliberate goal to bring opera to the masses, the Festival also put on productions at the new public outdoor space later to be known as Chilhowee Park. The festival’s president was young attorney Joshua Caldwell, who was soon to found the extremely durable literary society known as the Irving Club (it still meets every Monday night). The stage manager for three of the operas was young widowed mother Lizzie Crozier French; later to be known as a suffragist, she was sister of pianist Ethelrod W. Crozier. The opera festival was not universally popular. Although two Knoxville newspapers enthusiastically supported the festival, the new, no-nonsense Knoxville Sentinel denounced it. These visiting musicians are often arrogant and rude, the editor observed, and Knoxville needs factories, not operas.

Emma Juch (1861-1939). (Wikipedia)

Perhaps modeled after a similar festival in Cincinnati, Knoxville’s Music Festival drew some big stars. The 1889 festival brought Vienna soprano Emma Juch—one of the world’s great prima donnas, she was then still in her 20s—and English-born operetta composer Victor Herbert, here as both a music director and a cello player. Only recently moved to America, Herbert was only 30, and not nearly as famous as he would be 20 years later.

But here’s a cultural inversion that pulls the rug out from our perceptions of popular music. Through all these years of excitement of witnessing musical performers on stage, Knoxvillians had rarely or never purchased a ticket to see and hear a musician performing any familiar American musical genre, like old-time fiddling. That arrived as a sort of droll surprise at Staub’s Opera House, at the very end of the first big opera festival in May, 1883. A formally dressed crowd was still seated, having heard the final soprano, that Saturday afternoon at 2 p.m., when a troop of more than a dozen mostly elderly men took the stage, carrying violins. They put on a show, claiming it to be a fiddling contest, to claim a prize of $25 in gold. Remarkably, the opera crowd remained seated, just to see what would happen. They were playing old-fashioned music, from “before the war,” modest tunes no one had ever seen performed before a real audience. Most folks had heard “Arkansas Traveler” and “Grey Eagle” at barn dances and around Market Square, but never in an auditorium, never mind one called an Opera House.

It was the sort of creative surprise you might expect at an imaginative music festival. Was it the world’s first country-music concert?

The Daily Tribune remarked that the fiddle contest was an “innovation” in the realm of festivals in general: “but Knoxville will make new departures. She is the metropolis of East Tennessee—the capital of a capital people. They are unlike any other people in the United States. They are sui generis, and for Knoxville to have a festival like any other city would be to forget her rugged rocks and rills….”

Perhaps that one extraordinary event represented the Victorian version of “Keep Knoxville Scruffy.” Soon after opening that door, fiddling contests became a common thing on Market Square.

***

In the 1880s, as the compact city grew in population to about 23,000, Knoxville experienced a general renaissance—its first sustainable public library, a literary weekly, several cultural carnivals, three rival daily newspapers, a championship baseball team, and an opera festival. They were all elemental parts of a booming city that was proud of itself, and had plenty to offer strangers from around the western world.

And during those music-festival years, other notable singers came and went. Independent of the festival, in October, 1883, Grau’s Opera Company put on Billee Taylor, a “nautical comedy opera” by young but doomed English composer Edward Solomon, starring Alonzo Hatch, several years after his debut at Staub’s.

Emma Abbott (1850-1891). (Wikipedia)

Better known was Emma Abbott, whose Grand Opera Company came to Staub’s to put on her operatic extravaganza, different operas on each of four nights, in 1885. The strong-willed Abbott, known as “the People’s Prima Donna,” was known to change operas to her liking, singing in English and sometimes adding familiar tunes reflecting a modern American sensibility.

The same year, a Bijou Opera Co.—no relation to the theater that was not yet built—performed a series including The Mikado, in the fall of 1885, another relatively recent show, and evidence that Gilbert and Sullivan’s sophisticated comedies had followers in Knoxville. Its star was Adelaide Randall, who had performed there more than once before. Also on the bill were Balfe’s The Bohemian Girl and The Bridal Trap, an English-language adaptation of an Audran comic opera. The troupe returned a year later with a similar lineup.

Girofle-Girofla, Lecocq’s wacky opera-bouffe, was one of the most talked-about performances of 1886, at Staub’s, another local production starring Mae Bates.

In November, 1890, the traveling Conried Opera Co. produced The Gypsy Baron, a recent three-act operetta by the Waltz King, Johann Strauss, as well as an older and less common work, Adolph Muller’s romantic opera, The King’s Fool, on separate nights at Staub’s.

Opera society, composed mostly of affluent Knoxvillians, many of whom had lived elsewhere, was part of the scene. One of local opera’s biggest supporters was a newcomer, Scottish industrialist Alexander Arthur, and his Boston wife Nellie. He was planning a sort of industrial axis at Cumberland Gap, Middlesborough, Ky., and Harrogate, Tenn., both named for admirable industrial cities in England.

Arthur became, in 1888, co-founder and vice president of the Mozart Choral Society—apparently an organization different from Knoxville’s Mozart Club of six years earlier. The Arthurs, who walked to the opera house from their home on West Hill, were notable for their dress, he in his top hat, carrying a cane.

And to complete the picture, those dandies with top hats and canes emerged from the Opera House to an African American tamale vendor named Harry Royston. After several hours seated in a theater that probably didn’t serve popcorn, it was nice to get a bite to eat.

Meanwhile, Welsh immigrants were in town in significant numbers to work in the iron foundry, bringing with them their strong backs and their singing traditions. There are stories of Welsh singing informally in Mechanicsville, where many of them lived. By 1890, they were going public with ticketed performances of their Eisteddfod events, some of them held downtown on Gay Street at McArthur’s Music House.

The Welsh community’s star singer, Will Richards, was singing in public choral groups by the 1880s, occasionally on Staub’s programs as a featured baritone, or, as sometimes described, bass. In 1891, the Atlanta Constitution described him as “one of the finest basso singers ever heard in the South.” He seems to have preferred popular songs like “Sweet Evalina” and the “Bandalero Song” to arias, perhaps part of the cultural shift of the Gay Nineties. He became a professional singer in Chicago, but frequently returned home, and always sang somewhere when he did. By the turn of the century, he was back at home in Mechanicsville, teaching voice.

The YMCA had its own singing Glee Club, introducing organist Frank Nelson, an eccentric genius of voice who became music director at St. John’s Episcopal and, for half a century, Knoxville’s singing impresario who groomed countless young sopranos for countless recitals for more than half a century to come.

The Marble City Quartette that included bass singer Robert DeArmond was a male singing group that emerged in the mid-1880s to be “a hit with the audience”: trained voices favoring sentimental and religious English-language songs like “Lighthouse by the Sea” and “Tenting on the Old Campground.”

One of the local singing stars of the 1890s was a New York-trained soprano publicized as Mrs. John Lamar Meek, who appeared at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, often performed at Staub’s, operatic tunes like Gounod’s “Grand Aria from the Queen of Sheba.” She was “noted for her clear soprano voice, which she used so freely for the pleasure of her friends and the general public.” Also known as Mary Fleming Meek, her name is now most recognizable for something she did decades later for her hometown’s local university: an especially popular tune that starts “On a hallowed hill in Tennessee…” It was UT’s Alma Mater. Ironically, she was not an alumna of UT, which did not admit female students when she attended Mary Washington College in Virginia.

It was an era of oddities. Forty years after his first singing appearance here, General Tom Thumb returned to Knoxville, this time with his diminutive wife, to perform at Staub’s in 1891.

Obviously expensive and nerve-wracking to produce, the big, unlikely Music Festival sputtered a bit in the 1890s, with an attempted revival in 1895, spearheaded by Peter Staub’s son, Fritz, when the Anderson Opera Company produced an “Opera Week” here. But for the last few decades of the 19th century, a week of nights on the town was likely to include something significantly operatic.

A year later, the Journal & Tribune hailed “the Greatest Musical Event in the History of Knoxville.” The November, 1896, concert was a joint concert of two Metropolitan Opera stars, Maine-born, Milan-trained soprano Lillian Nordica, the “Yankee Diva” whose greatest successes had been in Europe, and contralto Rosa Linde, both of whom would be pioneer voices as operatic recording artists. Rosa Linde, who had studied with the legendary diva Pauline Viardot in Paris, had performed here before, on the same stage with Emma Juch, back in ‘89. Advertised as the “First Dramatic Contralto of America,” she had a personal connection to Knoxville, in that it was the former home of her husband, Frank P. Wright, in the days when he worked for W.W. Woodruff’s hardware store on Gay Street. “The fact she has, by marriage, become a daughter of Tennessee,” noted the Journal & Tribune, “will add no little interest to her appearance here tonight.” She sang an aria from Verdi’s Don Carlos “Mon coeur souvre” from Samson and Delilah—which Saint-Saens himself had dedicated to the singer’s longtime teacher, Viardot—and a bit from Rossini’s Barber of Seville. Nordica sang from the French comic opera Mignon and Wagner’s Tannheuser.

The mega-show was called “Nordica-Linde”—ignoring tenor John C. Dempsey and bass William H. Rieger, who also performed that night, sometimes alongside the women. It was part of a series of shows, both vocal and instrumental, sponsored by the Gay Street music store McArthur and Sons, featuring touring members of the Metropolitan Opera. They packed the house. Many came from out of town. The only empty seats were the bad seats. “Practically every musician in the city, both amateur and professional, was in attendance,” noted the Sentinel, which had apparently made peace with the popularity of opera.

“This perhaps accounted for the enthusiastic applause which greeted nearly every number on the program. As a rule, Knoxville audiences are apt to be rather undemonstrative, but this was not the case Saturday evening.”

Through the 1890s came a regular diet of famous singers. Italian bass star Giuseppe Campanari performed at Staub’s in April, 1899, with a Boston orchestra. Details are scant.

Opera survived, if not with the same degree of popular fascination, in the era of ragtime. Staub’s Opera House became, more simply, Staub’s Theatre. In early 1908, Staub’s welcomed the regional premiere of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, put on by Henry Savage’s opera, less than two years after its American debut—but it was clear that opera would be less common in the 20th century.

Staub’s Theatre, circa 1900. (Alec Reidl Knoxville Postcard Collection./KHP.)

Tectonic plates were shifting. Culture is a moving target, and by the turn of the century, culture was proliferating, splintering, gestating. By then, Knoxville had several theaters, offering a few dozen new options, high and low: vaudeville, minstrel shows, Broadway-style musicals, magic acts, pantomimes, tableaux vivants, and popular music, as jazz was evolving—a phenomenon rapidly accelerating via phonograph records and later radio. And, of course, team sports. Baseball had arrived in Knoxville about the same time opera did, but the end of the century brought both football and basketball, the latter of which competed directly with performing arts, because it was often played in the evening.

And even as the city got bigger, it lost some of its opera stalwarts. “Mrs. Barton,” now widowed, retired from the stage. Alexander Arthur went broke with the Panic of 1893, and left his stylish wife at their home on West Hill Avenue to join the reckless Klondike gold rush. Mae Bates moved to New York to pursue her muse, returning to Knoxville only occasionally.

And a generation once enthralled with opera and the discovery of an enthusiastic Knoxville audience for it was passing away. E.W. Crozier, one of the original music-festival directors, died in 1902; his sister, once-famous singer Cornelia, blamed his sudden death at age 60 on the trauma of dealing directly with the violent murder of his brother, the eccentric aviation pioneer.

Elderly Peter Staub was mostly retired when he was killed in a horse-and-buggy accident on Clinch Avenue and Locust in 1904.

Gustavus Knabe’s obituary photo in 1906.

Gustavus Knabe, often called “Professor” through his association with UT, retired from the scene due to rheumatism in the mid-1890s. His death in 1906 brought accolades, obituaries noting that he was a German immigrant from Leipzig, a Union veteran, “the Father of Music” in Knoxville, and that he had composed some funeral marches, some of which were played at his own funeral. At the time, his son William Staub was leading what would become known as UT’s marching band. Not mentioned at all in his obituaries were the Philharmonic Society or any of the other opera projects of the eras of Turner Hall, Hoxsie Hall, and the Mozart Club. However, Fritz Staub, son of the late Peter Staub, was one of his pallbearers, and an honorary pallbearer was Prof. E.W. Steen, one of the recognizable local singers of the 1880s.

A few months later, Steen moved back to Ohio, where he died not long afterward. Of those who packed the houses to hear opera in the 1870s and ‘80s, only a few remained.

By the time of Knabe’s death, there was a fresh interest in classical music, but this time more of what people wanted to experience, either from the stage or from the audience, was mainly instrumental, performed by string quartets, quintets, and sextets in hotel lobbies. Leading this new movement was a conservatory-trained violinist and cellist from Cincinnati named Bertha Roth, who drew polite crowds with her quartet, and later her “Little Symphony.” Later known as Bertha Walburn Clark, she became one of the first women in American history to found and conduct a full-sized symphony orchestra.

Still, talented sopranos in affluent families worked to train their voices, and vocal music survived in recitals and church services. Lillian McMillan, of Fountain City, began singing in public places around 1896; later, sometimes by her stage name, Dorothy South, she enjoyed a minor Broadway career and toured abroad.

And high points were yet to come. Staub’s became better known as the Lyric in the 1920s, and often showed motion pictures. But in May, 1927, contralto Marian Anderson performed there in the old hall, for a mixed-race audience—12 years before she was forbidden to sing at Washington’s Constitution Hall, due to the color of her skin.

The old Opera House, getting a little shabby, had already been showing movies, but the stage where prima donnas once performed became better known for boxing and wrestling matches, as well as occasional live-radio broadcasts of country music, especially WNOX’s “Tennessee Barn Dance” in the 1940s, which featured dozens of rising stars, including Chet Atkins and the reconstituted Carter Family.

***

Knoxville’s Golden Age of opera was not completely forgotten. A graying generation remembered the excitement of that pageant of promising young singers, and occasionally persuaded a newspaper columnist to remind Knoxville of its musical past, so that the younger generations of the 1920s and ’30s and ’40s would be aware of it. A few could remember some names of standout sopranos and a few tenors, but were vague about dates and context, and back then nobody had any handy way to look them up. So those columns, often in a Sunday News-Sentinel, may have been of more interest to those who remembered than to those who didn’t. Those historical columns were often little more than listed clusters of remembered names, unfamiliar to most newspaper readers, names of singers who once, for a moment on a stage before several hundred Knoxvillians, seemed great.

Often the past seems mythological, representing eras so different they’re unreachable, but one musician of Knoxville’s first opera era survived into living memory. “Professor” Frank Nelson, began accompanying singers as a very young pianist at Staub’s during its heyday in the 1880s. He got to know Gustavus Knabe, “the Father of Music,” with whom he trained—before sojourning to Knabe’s home in Leipzig for further study. It was Nelson who performed Knabe’s most famous composition, the funeral march he’d written for President Andrew Johnson back in 1875, at Knabe’s own funeral in 1906. Knabe himself had requested it. For decades, Nelson directed choirs at both St. John’s and Temple Beth-El, while on the side grooming countless sopranos for countless recitals, most of which he organized himself. Never married, Nelson devoted his life to music, and became something of an eccentric—he was known to buy hats for people he encountered on the Gay Street sidewalk. He a familiar figure in town, frequently still performing at the organ or piano, until his death at age 89 in 1957.

Staub’s Opera House, aka the Lyric, the resonant wonder of its era, when Knoxville was just discovering the joys of musical performance, had been torn down the year before—for the construction of a department store that was never built.

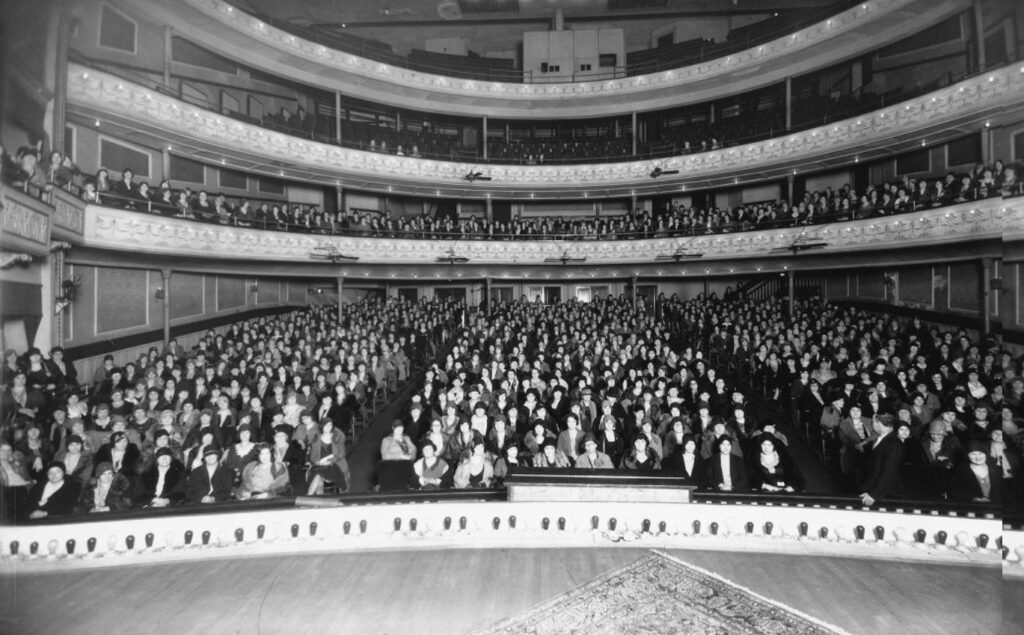

Interior of the Lyric Theatre, 1920s (former Staub’s Opera House). (McClung Historical Collection.)

They had called Knabe “The Father of Music in Knoxville,” or sometimes “The Father of Music in East Tennessee.” Today, in an era of hiphop, rock, and modern jazz, that title might seem overstating the case; there are lots of kinds of music, and Knabe was known entirely for the European classical sort. But he was the first person who inspired Knoxvillians to reach for something greater than the ordinary in the concert hall, the first to compel hundreds of strangers to buy tickets to hear any kind of music performed, and the inspiration for an era.

Knabe is buried under a flat, badly cracked slab of marble in a remote corner of Old Gray Cemetery. It’s not one of the stones you notice unless you’re looking for it.

By Jack Neely, October 2023

Leave a reply