A recent article in the News-Sentinel about Vol “Traditions” made me realize that my old alma mater’s traditions are constantly changing, and some are rather new. Most of those traditions listed were not things I knew about when I was at that same school, 40-odd years ago. The Vol Walk, for example. I looked it up. It seems to have been started deliberately in 1992, during Johnny Majors’ last season as coach.

I think The Rock was sanctified as such about that time. When I was at UT, it was there, but just a rock. As I understand it, that big chunk of limestone was unearthed in the mid-1960s, when they developed Fraternity Park, as part of an Urban Renewal project that had erased the middle-class neighborhood that had been there before, and landscape architects chose to keep it as a parking-lot landmark, not unlike what you see in some suburban commercial developments of that era, until someone thought of something better to do with it. When I was in school, it got tagged occasionally (did we say “tagged” then?), but never in a clever way that I recall. It was not something that we paid any attention to.

At the first few dozen football games I attended at Neyland Stadium, the only fight songs were “Down the Field” and “Fight, Vols, Fight.” As I started in college, the band occasionally played Rocky Top: kind of drolly, because the song is obviously not about people much interested in attending, or paying for, college. How did it catch on? If the lyrics do illustrate our UT ideal, we’re backsliding. We’re still having some issues with “smoggy smoke,” for example. Ain’t no telephone bills? Back then, when we sang that idyll about freedom from telephone bills, my only telephone bill was, as I recall, about $84 a year.

It’s a good deal more now, and I bet yours is, too. In the half-century since “Rocky Top” entered our consciousness, we’ve gone from daydreaming about no phones at all to a state of extreme dependency, not to say obedience, to our telephones and their associated bills.

Maybe we weren’t serious about that. But the song did indeed include the word “Tennessee,” and I think that’s mainly what we liked about it. In 1970, when it was a hit for Lynn Anderson, you rarely heard the word “Tennessee” on Top 40 radio. It got our attention.

***

But “Rocky Top” was coherent with an earlier cultural theme, surprising in some ways, and presented in several ways.

(Wikipedia)

“Rocky Top” has exotic origins. The song was written by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, neither of whom were originally from Tennessee. They were, in fact, both flatlanders: Boudleaux was from flat cotton country of southwestern Georgia, and as a young man performed as a violinist with the Atlanta Philharmonic, but later toured with a jazz band. Felice, who was born Mildred Genevieve Scaduto, who’s often given more credit for conceiving that song, was from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (Milwaukee also the home of Pee Wee King, co-author of “The Tennessee Waltz,” who performed on Knoxville’s “Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round in its earliest days.) Felice and Boudleaux met at a Milwaukee hotel where they were both working, married and moved to Nashville to become songwriters, and first became famous for several hits recorded by the Everly Brothers (the Everlys wrote a few of their own songs, but “Bye Bye Love” and “Wake Up Little Susie” were the Bryants’ creations). In the mid-1960s, the Bryants were visiting Gatlinburg, which was capitalizing on some hillbilly themes for the tourists who expected them, at a time when the nation’s most popular television comedy was “The Beverly Hillbillies.” Something in that mix of time and place seems to have inspired the Rocky Top idea. The Bryants later bought a house there.

Of course, the Rocky Top of the song is a fictional place. The real Rocky Top is a barren peak of Thunderhead Mountain, a spot probably never occupied for long by humans. But it may have suggested itself as a phrase.

By the fall of 1972, UT alum Howard Baker was employing a warm-up country band that played “Rocky Top” before his U.S. Senate campaign appearances.

The Pride of the Southland Band worked up a brassy, razzle-dazzle Broadway-style rendition of it to play at a football game, as kind of a novelty. According to UT sources, that started in 1972, but it seems not to have elicited much attention, because in the mid-‘70s, printed mentions of the song are rare. Of course, sportswriters who cover football games are rarely much interested in the band’s musical selections.

The first time I’ve found a contemporary reference to “Rocky Top” performed in direct connection with UT was in February 1973, during the old “All-Sing” competition at Alumni Memorial, when a non-fraternity group representing residential halls Reese and Humes sang it as part of a medley that also included Merle Haggard’s recent hit, “Okie from Muskogee.”

In May, 1975, Ava Barber, a young local performer and recording artist who had recently joined the Lawrence Welk show on TV, sang “Rocky Top” at one of Welk’s champagne-music concerts before a cheering crowd of more than 6,000 at Civic Coliseum.

Lamar Alexander used it in his successful gubernatorial campaign in 1978. That September, a group called the Rocky Top Cloggers performed at the Tennessee Valley Fair. Eight days later, the Bryants themselves were welcomed to a ball game at halftime in the UT-Oregon State game; by then, it had already been christened as a UT “pep song.”

In April, 1979, Hungarian-born conductor Zoltan Rozsnyai led the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra in what was almost certainly its first performance of “Rocky Top” as part of a first-ever country-pops night at the Coliseum. In March, 1980, it was played by a UT pep band as a pep song for heavyweight champ Big John Tate at a championship fight at old Stokely Athletic Center.

I don’t remember all that, don’t remember ever singing along when it was played. I don’t know when or why the additional “Woo!” was added. I’ve never actually participated, because I’m not certain what it means. But people do seem to enjoy it.

***

But that was all many years after the origin of the theme: Volunteer as Hillbilly. Before World War II, you don’t see that much at all.

Tennessee’s players had once been known as the Reds; that’s the color the early baseball teams wore in the 1870s. Orange gained dominance in the 1890s, reputedly thanks to a big summer crop of daisies on the Hill, and the team has been called the Volunteers, at first casually, since about 1902. It’s a fine name, except that it’s hard to picture. What does a Volunteer look like? It was in the late 1920s, just as Major Neyland’s football team was starting to make national waves, that the administration tried to nail it down.

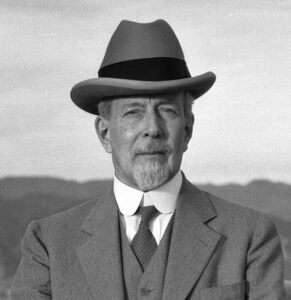

Lorado Taft (1860-1936). (Wikipedia)

In 1931, UT sponsored a nationwide contest to best exemplify the Volunteer spirit. To pick the best symbol, UT recruited a heavy hitter, Lorado Taft, the Chicago sculptor who was one of America’s most popular artists, known for his inspiring memorial statues and fountains. Taft was 70, but still taking commissions; UT probably couldn’t afford him, but brought the celebrity artist in to head a committee to choose the best depiction of a UT Volunteer for a future sculpture: that three-man committee included young Knoxville architect Charles Barber—at the top of his game, he had designed several recent buildings at UT—and local writer-artist Robert Lindsay Mason, whose recent book The Lure of the Smokies was regionally respected. Taft came here in person, on the Southern train.

The artist whose creation they picked was one Theodore Andre Beck, a fine-arts student at Yale. While Beck’s basic design, a man boldly stepping forward while carrying a torch and a winged-victory symbol, remained in the final product, some alumni advisors suggested changes, and for better or worse, the final product came out as a younger, more athletic-looking classical figure than in the award-winning design. It was originally intended to be a little taller, by the way, and to stand out prominently on Cumberland Avenue, but distractions and budget issues kicked the can down the road for more than 30 years. It was not actually finished and installed until 1968.

Today it’s a Greco-Roman figure, one who looks like he just stepped out of the Pantheon to see about that ruckus outside. Unless he later changed his name, Beck is fairly obscure; this appears to be his only famous work. By the time it was completed, the committee who had picked the original design—Taft, Barber, and Mason—had been dead for years, as were most of the administrators and donors who had celebrated the design with some fanfare back in 1931. My research hasn’t disclosed whether Beck lived to hear that it was finally erected.

And it went up about the same time as another, larger, bronze statue with a classical theme, within sight of it: Swedish sculptor Carl Milles’ “Europa and the Bull.” Both were 1968 installations on a rapidly changing campus.

Of course, by the time it went up, there had been other, less formal imaginings of what the Volunteer looked like. And there was a new song called “Rocky Top” just beginning to make the rounds, mainly in bluegrass circles, with no association with any university.

Those who think of Tennessee as limited and remote might find the Roman-style statue too pretentious to match their preconceptions of what passes for authentic. In fact several of UT’s traditions were even more exotic. An older tradition was the Aloha-Oe ceremony. Introduced in 1925 or 1926, it was the seniors’ formal farewell to campus, outdoors on the Hill or eventually in the stadium, with a torchlit crypto-Hawaiian theme. The fact of that Pacific-island influence on the old Hill may have seemed less bizarre in the 1920s, when during the era of the ukulele and the steel guitar, much of American culture was going Hawaiian. Togas were involved, perhaps suggesting a scarcity of authentic Hawaiian wear in Knoxville. Aloha-Oe seems to have lasted more than 40 years, fading in the late ’60s, as many traditions did, as both UT’s administration and student body preferred to jettison the Old to celebrate the Very New, though they were very different visions of what the New looked like.

But some of that ’20s spirit may have returned, with annual Torch Night. Maybe not as big a deal as Aloha Oe was, it has sputtered some over the years. When I was at UT, the only torch I ever saw was the one in the big bronze guy’s fist. Maybe I didn’t go to the right parties. I’ve heard a lot more about it in recent years.

And some UT traditions were pseudo-Native American, like the Nahheeyayli, launched in 1924, ostensibly as an homage to the Cherokee Dance of the Green Corn. The fraternity-dominated organization presented big-name bands at spring dances, and though attendees were ostensibly affluent white kids, they put on a diverse array of entertainment over the next 47 years, from Tommy Dorsey and Frank Sinatra to Harlem bandleader Chick Webb and civil-rights diva Nina Simone. After complaints about the organization’s exclusivity, it was disbanded in 1971, to be replaced by an officially approved UT planning organization.

Otherwise, concerning traditions, UT’s Pride of the Southland Marching Band’s wardrobe may suggest a reference to the Napoleonic era, and perhaps reflecting the original Tennessee Volunteers of the War of 1812 era—but then, most college marching bands wear similar uniforms, so that may be coincidence.

Also demonstrating some exotic influence are UT’s standard fight songs, both introduced in the 1930s, during the first half of Coach Robert Neyland’s tenure, when the football Vols were rising to national prominence. Long before professional football was overwhelmingly popular, the second quarter of the 20th century, 1925-1950, was probably the all-time high tide of national interest in college football. The fact that the Vols were cresting during that era may have a lot to do with why football caught on so thoroughly here, and engendered several traditions.

“Down the Field” was originally the fight song of Yale, written by an undergraduate there; Yale adopted it in 1904 and still uses it. Tennessee never plays Yale, so there’s no risk of confusion on the field.

It’s interesting that was adopted in 1931, the same year UT favored a Yale student’s depiction of UT’s “Volunteer” symbol. That connection to an Ivy League college almost 800 miles away, in Connecticut, is not utterly weird. In the 19th Century, when Knoxville’s elite regarded UT to be the local vocational school, many of the local wealthy sent their sons to Yale, probably more than to any other Ivy-League school. Yale Avenue, an old residential street near campus, left a scrap of itself on UT’s campus until it was renamed Peyton Manning Pass in 1997.

Knoxville-raised Lee “Bum” McClung (1870-1914), whose father went to UT and started a baseball team, was Yale’s football-team captain and one of that Ivy League school’s first big football stars in the 1880s, and returned to his hometown to encourage some of Knoxville’s earliest football squads in the early 1890s—just before the Vols coalesced as a competitive team. Yale’s hero—“a type Yale men idealize for emulation,” as the Washington Post called him, is buried at our Old Gray Cemetery, and can be considered, if not the godfather, at least a kindly uncle of UT football.

UT’s version of “Down the Field” has original words, different from Yale’s, though they’re rarely heard: “backing our football team / faltering never.” Its presumed time of adoption, 1931, seems relevant: jazz singer Rudy Vallee, at the height of his pop-idol fame, had just recorded a medley of Yale songs, prominently that one, in 1930. Yale’s lyrics, as sung by Vallee, are very specifically about beating Harvard, as if that was the only opponent that mattered; UT’s lyrics are not about Harvard at all.

There seems to be some murkiness about who wrote them. Cassandra Sproles, in the UT publication The Torchbearer stated in 2017 that they were written by UT engineering professor Clayton Matthews, who when he came to UT in 1907 to teach drawing and machine design was already notable in Illinois for introducing the new idea of acrobatic cheerleading. However, Betsey Creekmore, in the official UT source Volopedia, says they’re credited to Sam Gobble. He was a jazz trombonist performing around town then, formerly of Paul Whiteman’s famous orchestra, but in 1931, when he’s said to have written “Down the Field,” Gobble was associated with Maynard Baird’s Southern Serenaders, the Knoxville-based dance band. Gobble also wrote “Spirit of the Hill.”

“Fight, Vols, Fight,” the familiar staccato fight theme—again with lyrics rarely heard—also has origins far from Tennessee. It was written expressly for the Vols, but by a California songwriting trio, Milo Sweet, Gwen Sweet, and Thornton Allen, and introduced near the end of Tennessee’s impressive 1938 season.

***

But despite some evidence of local originality, before World War II, the main influences on UT’s popular identity were collegiate-generic. An Ivy-League pep song, Napoleonic band uniforms, and a classically Greco-Roman ideal of “The Volunteer.” To early UT boosters, it was much more important for UT to seem like a college than like a college in East Tennessee.

Roy Acuff (1903-1992). (Knoxville Journal)

That changed, and as was the case with the Hawaiian theme of the 1920s, it may have reflected national trends. After 1940, Hillbillies were suddenly cool. Did the opening and marketing of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, ca. 1930, play a role? That’s a subject for a graduate thesis. But by 1945, two of the most popular comic strips in America were Snuffy Smith and Li’l Abner, the latter of which was celebrated in motion pictures and a Broadway musical. The Ma and Pa Kettle movies were having their day. And some of the most popular musicians in the nation belonged to the relatively new genre marketed as Hillbilly. Among them were Knoxville’s own Roy Acuff and Archie Campbell, both of whom portrayed Hillbilly characters as part of their acts, with ratty straw hats, blacked-out teeth, and a jug of moonshine. Before Acuff, son of a Knoxville attorney, began having fun on stage with his band, the Crazy Tennesseans, country music was usually solemnly presented, sentimental old-time tunes often by performers in jackets and ties. That changed utterly in the 1930s. They started calling it Hillbilly.

Hillbilly Chic was a trend more popular with youth than their elders: casual, rebellious, independent, irreverent, hilarious, unapologetically pleasure-seeking, a hillbilly was everything a college undergrad wants to be. It would appear that by 1945, as bluegrass was just becoming popular, most of America admired the hillbilly esthetic. UT may have felt that it had an inside track. In the postwar 1940s, the image of Snuffy Smith began appearing on postwar UT Vols football programs, as if he were a Vol fan, himself.

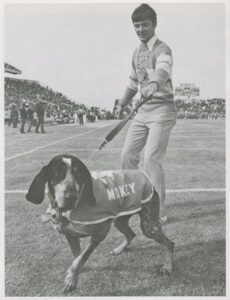

My father was an earnest, quiet, industrial engineering student at the same time that he was part of UT’s hillbilly revival, about 70 years ago. He was never sure where the Smokey the Dog idea came from, but in 1954 he was UT’s official Hillbilly, carrying a shootin’ iron and walking Smokey around the sidelines. The idea originated with students, he said, and it didn’t find many friends in UT’s administration. UT’s president was C.E. Brehm, a horticulture specialist from Pennsylvania who had taught at Purdue. They didn’t see what hillbilly ideals had to do with a university. Dad and his chums just thought it was funny. Talking to him, I got the feeling that part of what made it appealing was that their elders didn’t like it.

It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to call the Hillbilly a prototype of the Hippie.

Over the years, perhaps also with the aid of national popular culture, the Hillbilly, in overalls and floppy hat, seemed to evolve into the coonskin-cap pioneer. The Davy Crockett-style character, perhaps owing something to Fess Parker’s portrayal of the “King of the Wild Frontier” in globally popular Disney movies in 1954-55, became a sideline stalwart at Vols games of the post-Neyland era, a more Tennessee-specific personification of the Volunteer ideal than represented in the classical (but still-unbuilt) Volunteer statue. Crockett was a Tennessean, and he was a member of the cadre of Volunteers who fought the British in the War of 1812. He was a bit of a Hillbilly, too. Of course, he was no college man.

But it wasn’t just homo sapiens sorts who were representing the volunteer spirit in the 1950s. Most other SEC teams had animals mascots: Wildcats, Bulldogs, Tigers, Gators, Gamecocks. They could be an oversized costumed character who could exhort the crowds, or a very profitable plush toy. But what quadruped is associated with a Volunteer?

During that first blush of Hillbilly Chic, there came Smokey, the Bluetick Hound. The very term seems to evoke the colorful speech of old-time mountain folks. You didn’t even have to know what a bluetick hound looked like before you imagined it sleeping under an unpainted porch up in the remote hills, where folks get their corn from a jar.

However, assumptions can be deceiving. Even Smokey has exotic origins. If Smokey was not present at the first game on Shields-Watkins Field in 1921, it may have been partly because his breed wasn’t around yet.

Chances are, your great-grandparents were not familiar with the term. It’s a 20th-century neologism; though it may have emerged around 1915, I haven’t found the phrase “blue-tick” in reference to any sort of dog in newspapers before the mid-1930s—when the nation was electrified with radio and some movies were in technicolor, and Major Neyland’s Vols were already becoming a national phenomenon.

Smokey, a Blue-Tick Hound, at Neyland Stadium, 1978. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

According to Wikipedia and its credible-looking sources, the breed actually originated in Louisiana, a new adaptation of a celebrated French breed known as the Grand Bleu de Gascogne, said to have been brought to America about 200 years ago by the Marquis de Lafayette.

The United Kennel Club didn’t recognize the bluetick refinement as a separate breed until 1946. That was not long before Smokey started showing up at the Shields-Watkins sidelines in 1953. Over the years, he has been represented by a series of actual dogs that require handlers, who are today not Hillbillies but mainly healthy-looking young people in clean tennis shoes and modern athletic togs.

After half a century, “Rocky Top’s” domination of UT culture continues to grow. TV news journalists have begun to use “Rocky Top” as shorthand for UT campus, as if the place in the song, blissfully free of telephones, is the same place where little robots skitter around campus. If the Volunteer statue had been designed today, it might wear a bronze coonskin cap, favoring a moonshine jug to Winged Victory. But before you start raising money for that installation, give it some thought. The Volunteer ideal may evolve some more.

– Jack Neely, September 2023

Leave a reply