THE ROLE A COMPLEX CITY PLAYED IN A DIRECTOR’S CAREER

Knoxville’s primary contribution to the creation of Hollywood’s film industry has gotten more attention recently with the publication of a thick and well-received biography by Irish scholar Gwenda Young, called Hollywood’s Forgotten Master. Nominated for six Academy Awards for Best Director, Clarence Brown (1890-1987), created several classics, no two of them very much like each other as if he were experimenting with creating a new genre with each one, including A Woman of Affairs, Night Flight, Anna Christie, The Human Comedy, The Yearling, National Velvet, and Intruder in the Dust, making stars of Greta Garbo, Clark Gable, Elizabeth Taylor, and others, but is still not as well-known as several of his contemporaries who focused on individual genres.

Clarence Brown (1890-1987) (Wikipedia)

Focusing much more on Clarence Brown’s Hollywood years, from the early 1920s to the early 1950s, than on his youth, Young describes a patient and technically innovative movie maker with an unusual facility for getting along with problematic personalities. His creative use of machinery and his expertise with the interplay of light and motion helped refine the art of the motion picture. And his ability to get a large film crew away from the sound stages and back lots to shoot movies on location, in small towns thousands of miles away or sometimes in problematic wilderness settings, made many of his shoots adventures, sometimes dangerous ones. Young attributes Brown’s success, along with innovations to moviemaking shared with other directors, to his education and background as a trained engineer.

Knoxville, especially the University of Tennessee, which granted him two degrees in engineering back in 1910, has been happy to call Clarence Brown its own, even though he wasn’t born here, didn’t study cinema here, and never shot a movie here. What’s Knoxville’s main claim on this significant career in the motion-picture industry?

His engineering background, which was almost entirely based at UT, may be the main answer. But by the time he enrolled in classes on the Hill, he’d also been on the fringes of show business in Knoxville, arguably one of the city’s most acclaimed junior thespians.

Brown was born in Clinton, Massachusetts, in 1890. Exactly when the Browns arrived in Knoxville is a little vague. The director’s father, Larkin Brown, became a very prominent citizen here, but drew no attention when he arrived with his wife and son. Some sources published in the director’s lifetime suggest they moved here around 1900 or 1901; it’s not clear they were here before 1902. Knoxville was then a compact and rapidly changing industrial city of about 35,000, with two daily newspapers, a teeming market square with a relatively new and capacious Market House, a large old European-style opera theater, and a growing electric streetcar network. The Southern Railway terminal on Depot Street, replacing the old Civil War-era depot, was under construction in 1902. The city was growing so fast that the day the new station opened, it was already overcrowded, deemed to be too small, calling for an unplanned addition.

Some of the first evidence of the Brown family’s arrival in Knoxville is not related to anything either parent did, but a mention of their remarkable son, Clarence, who caught the attention of Knoxville newspapers when he was only 12 years old, the short kid from Massachusetts.

But to say the Browns were from Massachusetts is oversimplifying the matter.

The head of their small household, Larkin Brown, was a second-generation cotton-mill professional. Since before the Civil War, the Browns had been in the cotton-processing business in North Georgia. Clarence’s grandparents apparently fled the Confederacy for safety; it’s remarkable how many Southern families, regardless of any war-related sympathies, opted to head north when the shooting started. Larkin Brown was born in Pennsylvania in 1866, but a few years later, the family moved back to the South, to Alabama. The elder Browns eventually moved back to Atlanta, but as an adult, Larkin went north for work in what he knew best, and found it at a cotton mill in Massachusetts. There he met Catherine Gaw, an immigrant weaver from County Down, Ireland, about three years older than Larkin.

They married, and their son, Clarence, was born in May, 1890. Clarence Brown’s earliest memories were of small-town New England.

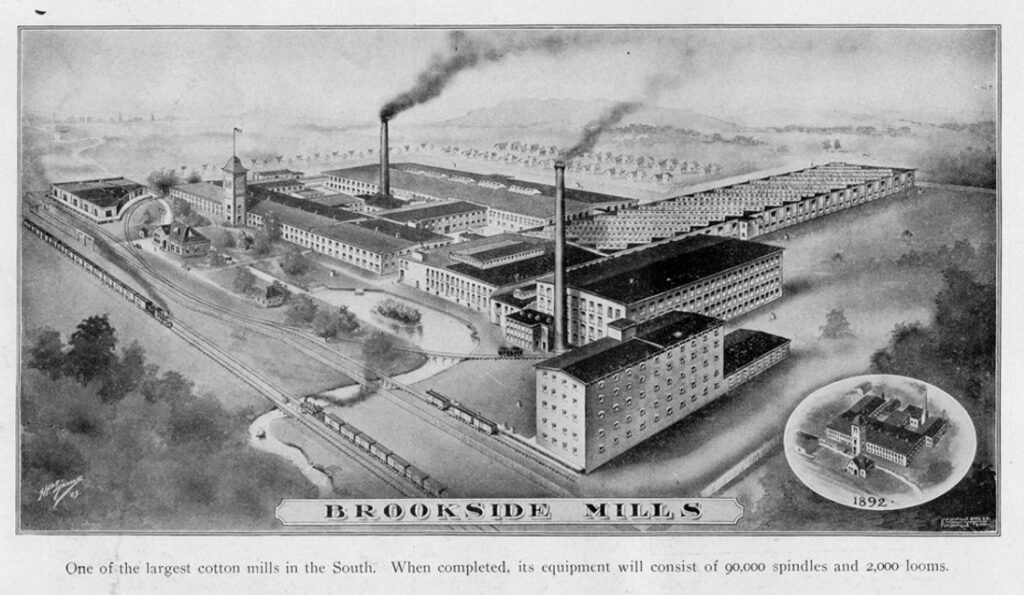

Larkin Brown was not a college man, and was first known as a loom repairman, but his credentials were sufficiently impressive to the executives at Knoxville’s Brookside Mills. Located along Second Creek, as well as the Southern railroad line, on the northwest side of town, Brookside was an upper-tier textile mill that specialized in weaving cotton, creating complex specialty fabrics like corduroy and velvet.

Although cotton fields were scarce in East Tennessee, Knoxville’s work force and railroad connections made it appealing for cotton-related industries. Founded in 1885, Brookside became one of Knoxville’s biggest factories of any kind, with a workforce of well over 1,000, producing more than 15 million yards of cloth annually. Because women were believed to be skilled at working with fabric, textile mills employed women at much higher rates than any other factories; almost half of Brookside’s employees were women.

Most of Brooksides employees, whether those in management, or those stationed at one of the mill’s 1,318 looms all day, lived nearby, within walking distance. In 1902, only daring young sportsmen had automobiles, and horses were known mostly to farmers and the wealthy. Everybody else walked or rode the electric streetcar. So Brookside’s employees, high and low, lived around the western portion of what had been known as North Knoxville, first incorporated into the city proper in 1897, just five years before the Browns’ arrival. They first lived in a modest house at 206 East Anderson, then moved to 105 East Baxter Avenue. They were lower middle-class homes, all just a few steps away from the little milltown commercial district along North Central that was already becoming known as Happy Holler.

Just to the west were the busy Southern Railway tracks, carrying both freight and passenger cars, and not far away, that railroad’s impressively large Coster Shops, a national repair and construction facility for railroad cars and engines. Seeing the trains may have made an impression on young Clarence, a part of his neighborhood worth noting considering the creative use he made of moving trains in some of his films.

Although Larkin Brown would become a significant figure in Knoxville business circles, he was little known in his first several years here. It says something that the first few times Larkin Brown’s name appears in the paper, it was because he was the father of the remarkable young performer named Clarence. From their first year in Knoxville, Clarence Brown was something of a star in a performance genre now almost forgotten.

He first enrolled at North Knoxville Public School. Later called the Mynders School, it was two-story brick elementary school with a three-story bell tower, located at Pearl Place, off Central, and very near the Browns’ early home on Baxter Avenue. Considered “one of the most progressive schools in the city,” North Knoxville P.S. was run by much-respected “Professor” J.R. Lowry, later principal of Park City High.

In Knoxville, the first decade of the 20th century was a fascinating and unpredictable period of almost constant experimentation with entertainment. It was the era of pageants, tableaux vivants, pantomimes, operettas, musical comedies, string quartets, soprano recitals, on-stage acrobatics, puppetry, dog and pony shows, spectacles of all sorts. It was also, of course, the era of blackface minstrel shows, which were popular across racial lines in that era, as they were for decades to come on Broadway and in Hollywood. If they seemed innocuous at the time, it may have been because vaudeville shows also featured troupes that specialized in ridiculing Germans, Irish, and hillbillies. But the racial stereotyping inherent in the form was sometimes meaner, and likely sharpened discrimination and segregation, which grew harsher during the blackface era.

Stages featured mostly live actors and singers, but more and more during that first decade, a bit of film on the magic lantern. A night on the town in 1902 Knoxville was almost guaranteed to surprise. Churches, schools, and charities often mimicked what was at Staub’s Theatre and the other vaudeville stages of Gay Street.

A popular entertainment of the era, the “Recitation” was a dramatic performance of a poem or story from memory. Unless you count stand-up comedy, which perhaps evolved from it, the recitation has very nearly died out in our time. But about 120 years ago, little Clarence Brown was mastering the discipline, a form of acting.

He was only 12 when his performances were already gaining the attention of the newspapers. In November, 1902, schoolteachers and students at North Knoxville schools put together an impressive project called “A Trip Around the World.” A progressive educational party at five different houses, it presented customs in fashion and food from the British Isles, France, Turkey, Japan and China, and the United States. Representing the U.S. Navy with a recitation was the new kid from Massachusetts.

“Clarence Brown recited a number of pieces, and made quite a hit,” reported the Journal & Tribune. It was, perhaps, his first review. Some actors devote their lives to drama and never get to read a line like that.

The following May, 1903, he recited at the Moses School in Mechanicsville, a ticketed fundraiser to purchase a piano. Brown, who turned 13 that month, was performing on the same stage as university musicians. Later the same month, he did another recitation at his home school, on a program shared with Cincinnati-trained violinist Bertha Roth: later to be better known as Bertha Walburn Clark. Again, the new kid was singled out for praise: Most of the young performers were not mentioned in the Knoxville Sentinel review, but “The recitation of Clarence Brown was well received.”

An unusually eclectic August event celebrating both the culture of the Rocky Mountains and of India, held at Third Presbyterian Church, on Fifth Avenue, was another triumph. “Clarence Brown delivered an address which was received with continued applause,” reported the Journal & Tribune. He was back for another variety show at the same venue on December 28, and the Sentinel noted, “Master Clarence Brown, one of the best in the city, recited an amusing Christmas piece.”

In February, 1904, he gave a recitation at a “Valentine Social” at Second Baptist, and the Sentinel reported the he “was heartily applauded. This youth has developed considerable talent in this line.”

Where he picked up that talent is interesting to speculate. There’s some evidence suggesting that Brown began the study in his early childhood. But one of the Browns’ close north-side neighbors—she lived on the same block just diagonally across the street, at 122 East Baxter—was one unusual woman with an unusual background in that performance art.

Laura Tidd Fogelsong was a dramatics teacher who offered classes in what was then known as “expression.” About 15 years older than Brown, she had Ohio roots, having performed in Cincinnati and trained with experts at the Columbus School of Oratory, as well as the Currie School of Expression in Boston. She was a 1901 graduate of the King’s School of Oratory in Pittsburgh, where she was said to have been a standout.

Wife of a bank executive, the vice president of the Knoxville Savings & Loan, she apparently arrived in Knoxville about the same time the Browns did, and was still in her 20s when she developed a reputation as a dramatics teacher in Knoxville, a specialist in “elocution, pantomime, and Delsarte”—the last being a physical expression of emotion akin to modern dance.

She quickly became well known in Knoxville society. For a time Fogelsong ran a formal studio on the 400 block of Gay Street, teaching her students and working with both theaters and churches to put on variety shows and minor spectacles involving well-known musicians. Some were conventional, featuring readings of Keats, Poe, Shakespeare, or Longfellow; some sound bizarre, like the pageant “The Microbe of Love.” She had younger children of her own, and most of her students were girls, but she developed an uncommonly close relationship with her “star pupil,” Clarence Brown.

Her name was barely known in Knoxville before his was. They became locally famous together. On occasion, they performed together, presented as “A Pair of Lunatics.”

Hence, before he even turned 14, Clarence Brown was already a local star. Under the headline “Coming Elocutionist,” in April, 1904, the Sentinel ran a short profile, illustrated with a portrait of a formally dressed, confident-looking young man.

Knoxville Sentinel, April 16, 1904.

“At a very early age his parents had him commence the study of elocution, which he has continued, under the best teachers in the east, up to the present time, being now under the instruction of Mrs. Fogelsong, in this city. His conception and rendition of the very difficult arena scene from Quo Vadis was indeed remarkable for one of his tender years, being but 13 years of age.” He had performed that one at the Asylum Avenue Methodist Church, now known as Second Methodist.

“He has a great variety of selections, being able to recite from the sublime to the ridiculous, from the pathetic to the humorous.” The unnamed reporter adds, “All who know him speak of him as a boy of remarkable intelligence, with a brilliant future before him.”

In July, 1904, he traveled to Atlanta to perform before a reported audience of 6,000 at the Grand Opera House. Sponsored by the Eagles, it was part of a lengthy and bizarre variety show that included blackface minstrelsy, wooden-shoe dancing, acrobatics, boxing, and little Clarence Brown’s piece, “How Ruby Played.” That November, Brown won a gold medal for elocution: the Sentinel described him as “the talented young elocutionist who has creditably appeared in several entertainments.”

He graduated from the North Knoxville School in 1904, as an “honor pupil,” indicating mainly that he never missed class.

He also showed some talent as a carpenter, one of only seven boys in his school who proved he could build a “mission chair,” a stylish arts-and-crafts design, in the workshop.

As author Young points out, and as some actors like Katharine Hepburn observed—Brown and Hepburn worked together on the 1947 Schumann biopic, Song of Love—Brown was known in Hollywood for his “dual nature,” his unusual combination of enthusiasms, both artistic and mechanical. According to Hepburn, he was “by nature highly romantic, by education, an engineer.”

It started very young, as he was both what we might now call a theater nerd and a gearhead. Besides dramatics, Brown was unusually interested in all the new technology, especially the automobile and the airplane. Some acquaintances later recalled the famous director as a big fan of Tom Swift novels. It may not seem surprising at first. The Swift books were mostly about new technology—Tom Swift and his Airship, Tom Swift and His Runabout, Tom Swift and his Submarine Boat, Tom Swift and His Sky Racer. The adult Brown loved mechanical things, and fast things, drove fast cars and flew airplanes. However, the very first Tom Swift books came out in 1910, the year Brown turned 20 and graduated from college. Was he really reading boys’ books? Granted, those were especially interesting ones illustrating a rapidly changing time. Maybe he was.

Clarence Brown entered Knoxville High School, still often known as Girls High School, in 1904, as it began accepting male students and deftly changed its name to Knoxville High. Although he may not have attended for more than one year, the palatial school on Union Avenue would play a significant role in his life and his memories of Knoxville, even in the director’s chair.

Girl’s High School on Union Avenue at Walnut Street, circa 1895. (McClung Historical Collection.)

He was an active kid, young for his grade and short for his age—he never got past 5’7—and forever remembered by his classmates as the last kid who wore short pants to school, in an era when they were associated with children. He apparently didn’t mind. At KHS he joined the Art Club, the Dramatic Club, the Musical Club. One image from a yearbook shows him with a triangular-bodied mandolin.

His new school was already developing a bit of a literary reputation. Among its teachers at the time the Browns arrived in town were Anne Waldron, later known as Anne Armstrong, who would enjoy a national profile as a leading business woman, sometime lecturer at Harvard, whose two novels—one of them called The Seas of God was based in a slightly fictionalized Knoxville—would gain international attention. She taught 10th grade at Girls High until 1902.

Graduating that year from the big school on Union was Ruth Hale, daughter of a controversial antisuffragist teacher, Annie Riley Hale. As a New York journalist and feminist, Ruth Hale was a core member of New York’s jazz-age legend, the Algonquin Round Table. (Hale is portrayed by Jane Adams in the 1994 film, Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle.)

Ruth’s younger brother was an aspiring opera star whose severe features put him in demand as a Hollywood character actor even in his old age, in TV shows from Perry Mason to Star Trek. Richard Hale and Clarence Brown may have overlapped as Knoxville public-school students for a brief period. Whether they knew each other here is a question worth asking, not only because the two were later familiar figures in Hollywood, but because they worked together on at least one movie. Almost half a century after they were both in Knoxville public schools, Richard Hale played the memorable role in one of Clarence Brown’s most popular movies, the original 1951 version of Angels in the Outfield. In that movie, Hale was the sarcastic atheist. Did they swap Knoxville public-school stories?

When asked about his favorite Knoxville teacher, Clarence Brown would respond, decades later, “Molly Hayes.” Formally Mary Agnes Hayes, the Knoxville native was a Catholic-trained teacher, deeply versed in literature and history, who had been teaching in Knoxville city schools since public education started, in the early 1870s, and was devoted herself to her profession. Although only occasionally in the public eye, in 1907 she gave a lecture to the Catholic Newman Club on the subject of “Historic and Scenic Preservation.” After she died in 1913, Brown contributed to her memorial stone, at Calvary Cemetery.

Occasionally Clarence Brown performed in conjunction with members of the Nicholson Art League, the large and lively organization of artists, architects, photographers, and dilettantes promoting the visual arts in Knoxville at the time. Their most celebrated member was oil painter Catherine Wiley, who worked as a prop artist on a program by the Ladies Aid to the Order of Railway Conductors in October, 1904, in which little Clarence Brown was one of the chief draws. Knoxville’s avatar of impressionist painting, Wiley was 11 years older than Brown; they would later be at UT at the same time.

Another close brush with an endeavor even more closely related to Brown’s future career was that hardly a block from the school, just down Walnut Street, was O.C. Wiley’s optical shop. Wiley sold cameras, the latest models. And working as a clerk in his shop, when Brown was at KHS, was a young man 10 years older than Brown, Jim Thompson. Already one of Knoxville’s most prolific photographers, he would make Knoxville’s first known motion pictures, just short, creative home movies—though probably not until after Brown had left town.

A memory the director may have evoked in his 1935 comedy, Ah, Wilderness! was Knoxville High’s holiday program of 1904.

“The entertainment will be one of the best ever given at the high school,” reported the Sentinel. “If they do what they say they will, there will be perhaps 300 in attendance.” The performers were reported to be “among the best of musical and literary talent in the city.” It would appear that all the performers that Friday evening, with the one exception of little Clarence Brown, were female.

Held on the school’s capacious third floor, the event closely resembles a scene in that movie, featuring previously little-known Mickey Rooney. Although the setting is a small town in New England in 1904, the interior of the building appears to closely resemble the Victorian KHS building Brown himself knew in 1904. It was a director’s addition to the Eugene O’Neill play, and several of Brown’s schoolmates in 1935 who watched the movie together at the Tennessee claimed they recognized not just the set, but the minor characters Brown had added, including imperfect recitation performers.

Brown became notable for reciting one story in particular, “How the LaRue Stakes Were Lost,” a once-familiar story about how a horse-racing jockey sacrificed a win to save a child. Brown read it at Staub’s Theatre, Knoxville’s biggest venue in 1905, when his Knoxville High School class graduated. According to the newspaper accounts, a few aldermen in the balcony, including J.P. Murphy, the colorful “Mayor of Irish Town,” broke out in guffaws at Clarence’s reading—which may have been intended to be humorous.

It was a little unusual but not freakish to graduate days after turning 15; at the time, Knoxville High School presented diplomas after 10th grade.

***

Only occasionally mentioned in the Clarence Brown story is his remarkable father.

In his first decade in Knoxville, Larkin Brown, who came to town as an unknown but by 1903 was “assistant superintendent” at Brookside Mills, gradually became an important business and community leader. He was one of a few hundred ambitious businessmen who joined the Knoxville Board of Trade in 1905. In the summer of 1906, he had a formal role in planning the big annual Brookside Picnic at Chilhowee Park. Perhaps riding on his son’s coattails, he was in charge of entertainment.

By 1909, Larkin became general manager of Brookside Mills. He was a supervisor of the factory’s construction of a 152-foot-tall smokestack, one of the tallest structures in Knoxville at the time. Clarence Brown would remember the thrill of climbing all the way up, ostensibly with his father’s permission.

Brookside Mills, circa 1903. (Knoxville History Project.)

Even as Larkin Brown rose in power and influence at one of Knoxville’s biggest factories, and then in various philanthropies and Knoxville-boosting organizations, the Browns were socially modest. Newspapers mentioned their trips to see Brown’s family in Atlanta, or on rare occasions when they entertained old friends from Massachusetts. They’re not often listed as participants in dances or other social affairs.

In the records, Clarence’s mother only occasionally appears. It’s not very obvious that Catherine Brown found a place for herself in Knoxville, other than within her family. But in 1908 her sewing skills earned her first prize in a downtown department store’s garment-making competition, in the “shirtwaist” category. In 1915, she was a chaperone for an outing of the Aeolian Club, which combined live classical music and camping out in a way probably unknown today.

They had been Baptists in Massachusetts, but may have tried a few other denominations in Knoxville before settling as Episcopalians at St. John’s. It was the city’s social-register church, and it’s interesting that Larkin sometimes represented the congregation as a spokesman. He knew and worked with several of the most powerful men in Knoxville, notably fellow parishioner, army officer, and textile-mill executive L.D. Tyson, with whom he sometimes traveled on business. Cherokee Country Club opened when Larkin was rising fast in management at Brookside, but there’s no evidence they ever accepted any invitations there, assuming any ever came.

***

The year Clarence Brown started at UT, it would seem that he would continue to gain plaudits for his well-practiced creative recitations. “Although quite young, he has made for himself quite a reputation as an elocutionist and impersonator,” the Journal & Tribune remarked in 1905.

Today, planners tend not to host public events on Thanksgiving evening, but in 1905, the Railroad YMCA on Depot Street hosted a variety show including Brown performing something called “The Yankee in Love.”

Later that year, he performed on the same stage with Lillian McMillan in a “college spectacle” called Professor Napoleon, in a blackface role as “Mascot Sambo.” The star of the show, “Miss McMillan,” seemed to be going places, and in fact Lillian McMillan was soon to appear in several Broadway musicals, and later toured Canada and Australia as a dramatic singer, often under her stage name “Dorothy South.”

Show biz is a broad concept. Young “Brownie” often shared a stage with cornet solos and phonograph demonstrations. One outdoor event at Riverside Park featured his recitations and “a most wonderful elephant to ride.”

***

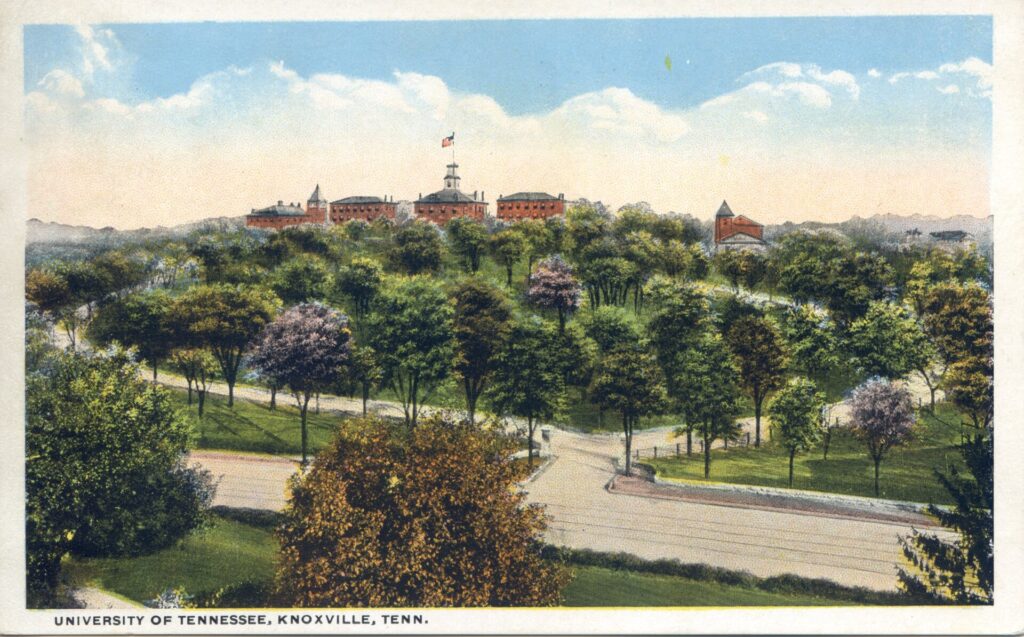

UT was an interesting old place in 1905, nothing grandiose about it, just a hilltop cluster of old brick buildings, some of them dating back to 1828, including melancholy Old College, with its bell tower, which still showed scars from Confederate shelling during the siege of 1863.

University of Tennessee’s the Hill, circa 1900. (Alec Riedl Knoxville Postcard Collection, KHP.)

He started at UT in the fall of 1905, as an engineering student. His father, who admired engineers, and worked with them, made public assertions that businessmen and engineers should work together. He wanted his son to go to college and study something serious, though it was obvious that the kid loved show biz, and to some degree the parents had encouraged that, too. UT offered no dramatic-arts program at the time. But maybe it offered a broad perspective in a lot of things, and people, that Clarence Brown found useful.

UT’s very active Board of Trustees included several graying and balding octogenarians who remembered the Civil War, including Union veteran Captain William Rule, venerable editor, historian, and former mayor whose former apprentice, Adolph Ochs, now ran the New York Times; author-attorney Oliver Perry Temple, another old Unionist, whose book about the war was well known and often quoted; and long-bearded Presbyterian Rev. James Park, sometimes described as “Class of ’40”—1840, that is. They were all active and involved in the university that Clarence Brown attended, none of them rare sights on the hilltop. Also on that same board were some prominent attorneys, like Joshua Caldwell, founder of the long-lived literary society called the Irving Club.

And among them was a regular lecturer at the university who spent more time on the Hill than most of the trustees. Edward Terry Sanford played a major role in establishing UT’s law school. If Clarence Brown never had a class with him, he likely saw him once or twice a week on that little campus. Sanford was a respected judge who would be tapped in 1921 to be a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. (Although he’s not as famous as some of his high-court peers, a recent biography by attorney Stephanie Slater makes the case that Sanford had a significant influence on federal law, especially in the realm of civil rights.)

***

Clarence Brown spent more time at UT’s Hill than most students do—five years, earning two degrees, and surely got to know all of these people, whether personally or to recognize on the sidewalk.

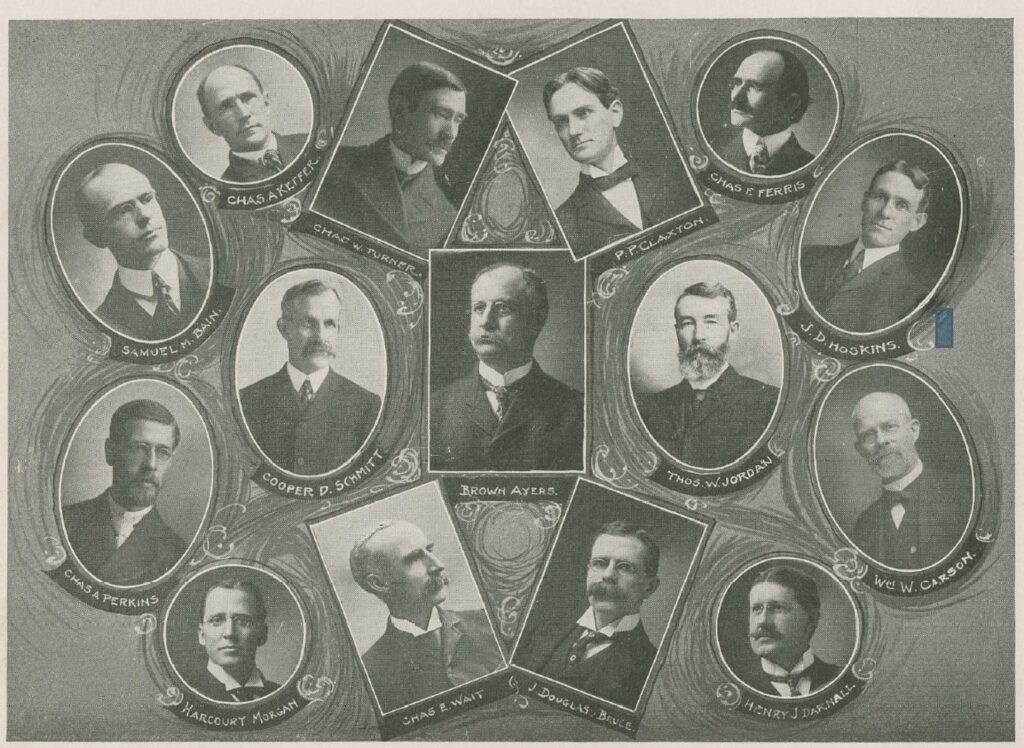

UT was still very small, with only a few hundred students, and the entire campus was clustered on the Hill. In charge was a relative newcomer, one with impressive credentials as a scientist. Brown Ayres, who had spent most of his career at Tulane, in New Orleans, was a genius of adapting the latest electricity-enabled technologies to practical use. He had consulted with Thomas Edison about transporting light bulbs, helped Alexander Graham Bell demonstrate the telephone, advised on the planning of New Orleans’ first electric streetcar. In the Crescent City he had a bit of a reputation as a wizard, showing to the public how X-rays worked, taking high-quality photographs of an eclipse, and demonstrating actual broadcasts of the new “wireless” radio.

Professor Ayres was in Knoxville as a distinguished Tulane scientist back in the summer of 1902, perhaps very soon after the Browns arrived from Massachusetts, when he presented Knoxville’s first demonstration of an actual wireless radio broadcast, between buildings on the Hill. It’s unknown whether newcomer Clarence was in the semi-public audience, but if he was like most 12-year-old boys at the time, was fascinated with this new technology.

Professor Ayres moved to Knoxville permanently, to accept the job of UT’s president, in 1904, just one year before Brown enrolled as a freshman. Presidents usually got to meet most undergraduate students back then, and Ayres in particular likely got to know the engineering students—but we have more specific reasons to believe that Brown and Ayres got to know each other. Brown dated Ayres’ daughter, Elizabeth, who lived with her parents in the presidential residence on the Hill. In that era, a father would certainly get to know the boys who were interested in his daughter. She was a couple of years younger than Clarence; their relationship lasted only until he graduated and left town.

Ayres was often preoccupied by administration and fundraising for much of his tenure, but he’s also sometimes listed on the engineering faculty, and it’s safe to say Clarence Brown got to hear Ayres lectures during his five years on the Hill.

It may say something about UT’s attitude toward its own heritage that only one building that Brown would have recognized remains on the modern campus: South College, on top of the Hill, is still there. It may also say something that several buildings on campus today are named for professors on the faculty during Brown’s five years there. He knew, or crossed paths with, several academics who are legendary in UT history: Ayres, Claxton, Morgan, Hoskins, Ferris, and Perkins are all the names of modern UT buildings. Most were professors that Clarence Brown knew personally.

UT Faculty members under President Brown Ayres included professors Charles Perkins, Charles Ferris, Harcourt Morgan and John Hoskins, many of whose names appear on UT buildings today. From UT Volunteer Yearbook, 1907. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

Although engineering had been a concentration of UT ever since 1869, when the university was the first southern school to be granted federal funding via the Morrill Act, which emphasized the practical sciences, engineering did not gain “College” status until about three years after Brown’s graduation. But it was obviously headed in that direction, as is evident in the quality of the professors teaching engineering during Brown’s period.

Perkins Hall is named for one of Brown’s engineering professors, Charles Albert Perkins (1858-1945), a Massachusetts-born scholar and author of books on electrical engineering, who had known Woodrow Wilson as a fellow student at Johns Hopkins; he taught engineering at UT for half a century, and during Brown’s period, was the local expert on electrical engineering, one of the future director’s concentrations.

Ferris Hall is named for Charles Edward Ferris (1864 -1951), another of Brown’s professors. From Ohio and Michigan, he had studied at Montreal’s McGill before coming to UT, where he first combined art and technology, teaching both “freehand art” and mechanical drawing, as head of the Machine Design and Drawing School. He eventually specialized in mechanical engineering. A diminutive man with shaggy eyebrows, he became UT’s first Dean of Engineering in 1913, and, like Perkins, became a nationally respected author of books on engineering, notably Manual for Engineers, sold nationally, which reportedly went through 25 editions.

Also an athlete, Ferris had played on some of UT’s earliest football teams—back when they sometimes allowed faculty members to join—and later led the major engineering effort that became known as Shields-Watkins Field. He found Brown to be an impressive student, and later took pride in the engineering aspects of his motion pictures. In 1939, Ferris remembered Brown, from almost 30 years earlier, as “a very immature but very keen fellow.” Ferris remarked that he had the impression that Brown entered engineering mainly because of his father’s interest in it, but that Brown later told Ferris that “engineering had been a great help to him in Hollywood, where a technical knowledge of power, machinery, and lights was a great advantage to the director.”

It’s intriguing that the engineering curriculum included professors who represented “Experimental Engineering.” One of them was John Albert Switzer; in 1914, as a hydraulic engineer, he wrote a book called The Water Powers of Tennessee, about the potential of hydraulic power, anticipating the Tennessee Valley Authority by almost 20 years.

Taken all together, the faculty Brown knew was a small but pretty impressive cadre of wide-ranging thinkers.

Harcourt Morgan, for whom Morgan Hall is named, was a Canadian-born entomologist who had known Ayres in Louisiana, where he was credited with making a dent in plagues of mosquitos and boll weevils; an agriculture professor and administrator at UT, he later became famous during the New Deal as one of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s original three directors, reporting to President Roosevelt.

Popular math professor Cooper Schmitt is memorialized inside the Austin Peay Building. His son, Bernadotte, who graduated just before Brown’s arrival as a freshman, was still a familiar figure on the campus area; a Rhodes scholar, he later won the Pulitzer Prize for History.

Moses Jacob was a professor of veterinary science. Although Brown’s two best-remembered movies involve a horse and a deer, he’s not known to have studied animal sciences at UT, but would likely have recognized Prof. Jacob. He would soon be involved in the effort to launch big agricultural fairs at Chilhowee Park. Today, the park’s Jacob Building is named for him.

John R. Neal, the attorney legendary for his abilities as for his severe eccentricities, taught law on the Hill during Brown’s final years. Later fired from UT, ostensibly for his unconventional behavior, he opened his own competing law school, and in 1925 became teacher John Scopes’ primary attorney during the famous “Monkey Trial” in Dayton, working not always gracefully with celebrity attorney Clarence Darrow. (Neal also makes a cameo in Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree.)

Also on the faculty for most of Brown’s time on the Hill was “freehand drawing” instructor Catherine Wiley, who at the same time was introducing impressionist painting to Knoxville, both with shows and lectures; today, with some of her work in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, she’s considered perhaps the greatest artist of her region and era. UT boasted an “Art Club” that in 1909 included Wiley; her sister, Eleanor Wiley, who was then an evangelist of the Craftsman approach to art and life; Mary Grainger, a teacher and painter who made a career in art; and Robert Lindsay Mason, who became a writer (The Lure of the Great Smokies) and, after tutelage from illustrators Howard Pyle and Maxfield Parrish, an influential arts teacher.

Considering that UT certainly had no film-studies program then, it may be a coincidence, but an interesting one, that the year before Brown enrolled, UT graduated a woman who would play a national role in the development of documentary film: Laura Thornburgh, Class of ’04, would become a notable expert in film, one who has been called the U.S. government’s first professional film editor. A Knoxville Sentinel reporter covering UT during Brown’s time, Thornburgh remained part of the UT family, and often on campus during Brown’s time on the Hill, especially in the coverage of performance-related events there.

***

UT’s education building is named for Philander Claxton, a flesh-and-blood professor of Clarence Brown’s era, moreover the progressive mind behind the unprecedented series of intellectual festivals known as the Summer School of the South. Aimed at an audience of professional teachers from many states—and more than 1,000 typically traveled to Knoxville to attend the on-campus event—it offered a lineup of nationally relevant speakers, including William Jennings Bryan, Jane Addams, John Dewey, Carl Sandburg, and hundreds of others, scientists, explorers, authors.

Professional teachers were the main audience. But at night, often thrown open to the public, Jefferson Hall, the makeshift “Pine Palace” built for the summer event in the quad, featured actors and musicians in performance. Among them was Charles Coburn, the Georgia native and interpreter of Shakespeare who was perhaps the most frequently seen actor during the whole Summer School era. Many years later, as a prolific character actor in Hollywood, Coburn would find important supporting roles in several of Clarence Brown’s MGM films, including Idiot’s Delight and the 1938 classic, Of Human Hearts.

Brown’s own fellow students left their mark on UT’s campus, too.

Another building on campus today is named for one of Brown’s engineering classmates: Nathan Dougherty, a football hero during Brown’s time, would be a longtime engineering professor and dean who earned prominence in national professional organizations, in 1958 named Outstanding Engineer of the Year. They were once in the same class, though Dougherty graduated before Brown.

Jessie Harris, a Texan who graduated in Brown’s class of only 44 students, worked for some years out west before returning to UT to expand its home-economics program into a college, at the same time working in trouble spots around the world to improve safety and nutrition for populations under stress.

Also in Brown’s intimate graduating class was a local legend: Nannie Lee Hicks, uncommonly beloved as a Central High history teacher and author on local history. Brown was also at UT at the same time as W.P. “Buck” Toms, a businessman, civic leader, and philanthropist, who graduated in 1907. The region’s main Boy Scout camp is named for him.

On a small campus, these people all knew, or at least recognized, each other. It was a pretty fascinating hill, considering everyone who climbed it: a good place to do some thinking and imagine a future with few boundaries.

During Brown’s last year at UT, one of his younger classmates was John Fanz Staub, two years younger than Brown. After a heroic period as a warplane pilot in World War I and a couple of graduate degrees from MIT, Staub became a nationally notable architect, best known for his giant creatively revivalist mansions in Texas, the subject of several books. He and Brown were both enthusiastic about aviation, later serving as military pilots during World War I. How well they knew each other at UT is unclear.

And it may be stretching a point, but still hard to ignore: at the foot of the Hill lived the intellectually remarkable Krutch family. Three years younger than Brown, Joseph Wood Krutch followed the future director’s UT era closely. The future Columbia scholar and New York critic, biographer, and seminal environmentalist won the National Book Award for a work of philosophy, but was perhaps best known in New York for his 28 years as a Broadway theater critic, and author of a book on modern drama.

Like Brown, Krutch had been notable as a public speaker even at Knoxville High, winning awards for oratory; and like Brown, Krutch was once especially interested in flying, and was just 17 when he became one of the first two Knoxville passengers to go aloft in a flying machine, during an East Knoxville exhibition in 1911 that, for all we know, Brown may have witnessed, his last year in town. Did they know each other? They would have had a lot to talk about.

***

That was the setting. We know a few more specific things about Brown’s time at UT. Early in 1906, Brown was becoming known as a debater, with the Philomathesian Literary Club at UT. More than “recitations,” his performances were now sometimes called “declamations”; he was sometimes called an “elocutionist” or, officially, “Declaimer.”

UT Volunteer Yearbook, 1908. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

At UT, he joined the Rouge and Powder Club, a previously all-female collegiate troupe that at least occasionally put on elaborate productions. Brown was one of only two men “in an intricate and perplexing situation” in a production called The Revenge of Shari Hot-Su: A Japanese Play in Two Acts.

In February, 1907, by request, he gave a pro-temperance recitation for a women’s group, called “Rock of Ages.” He won a statewide oratorical contest sponsored by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union that November—which happened to be the month that Knoxville voters chose to close their saloons.

Was the teenager opposed to liquor, or did he see it as another opportunity to practice his craft and impress a crowd? In years to come, Brown would be noted for creating colorful bar scenes in movies like Anna Christie and Ah, Wilderness.

In the late summer of 1907, he was one of “a large and jolly party of Knoxville young people” gender-balanced with nine boys and nine girls, who rode a “gasoline launch” up the French Broad to Rock House, a natural cliff formation that offered some shelter, for a 10-day camping trip involving horseback riding and fishing. And dancing: they took with them a phonograph for dancing at night.

In his first years at UT, Brown was involved with a wide variety of extracurricular organizations, from the German Club to the Tennis Club.

He once claimed to have greased the trolley tracks of the Cumberland Avenue streetcar, a common prank in that day. He was still a teenager, after all.

***

Even while studying engineering at UT, Brown remained close to Laura Fogelsong. When she organized an event at the Cable Hall, the piano showcase and venue on Gay Street, in October, 1907, Brown joined her for another recitation. On the same bill were pianist Frank Nelson, an interesting eccentric who, never married, devoted his life to musical performance, and was perhaps the leading impresarios of his era, helping groom several professional performers—and Bertha Walburn, the talented cellist from Cincinnati who would later found the durable Knoxville Symphony Orchestra, conducting it herself, one of the first women in American history to hold a baton in front of a full orchestra. But in 1907, she was best known as a hotel-lobby performer.

In that production, Brown’s parts included some Shakespeare as well as the “Arena Scene” from Quo Vadis, which at the time was known mainly as a Polish novel, as the bodyguard Ursus contends with the bulls. We can only guess how that was portrayed by the diminutive teenager Clarence Brown. (Brown never made a movie of Quo Vadis, but his younger MGM colleague Mervyn LeRoy had a major popular and critical success with an elaborately produced epic version in 1951, as Brown was contemplating retirement.)

Perhaps because the classical event at Cable Hall was more serious than most of the dozens of public events that had already featured Brown as a child, the Journal and Tribune regarded this performance, when he was 17, as a milestone. “The occasion marked the formal debut of Mr. Clarence Brown, who has already achieved quite a reputation for his ability to recite. He was the only one to respond to an encore during the evening.”

However, having hit that high note, the child prodigy began to retreat from Knoxville’s limelight. After 1907, Brown’s participation in extracurricular activities of all sorts, on campus and off, dwindles. Perhaps, being a full-time college student, he was studying engineering.

UT yearbooks suggest he was also less socially active in club activities as an upper classman than in his early years in college. He was originally a member of the Class of ’09, but didn’t graduate until ’10. Perhaps of necessity, he seems to have gotten more serious about engineering, eventually opting to get two degrees.

He did come out on stage one more time in late May, 1909, at the Pine Palace, that large auditorium built on the grassy quad atop the Hill. At the time, UT had no other big auditorium, as evidenced by the fact that Commencement was often held at Staub’s Theatre on Gay Street. Never meant to be permanent, Jefferson Hall, this large, cheap, temporary building built for the Summer School extravaganzas embarrassed some who wished for a more coherently collegiate look to the old college.

That May 21, the Pine Palace hosted a play called A Multitude of Masks, apparently a costumed comedy of manners. Prominent in the cast of seven, Clarence Brown was John Spencer Ellington, “bearer of an unwilling dukedom.”

Brown, who played the duke who was himself playing a butler, wasn’t singled out for praise, but the Journal and Tribune noted, “All parts were well taken, and the performance progresses smoothly from start to finish, pleasing the audience at every turn and provoking hearty applause.”

Held on a Friday, it was apparently a single-night performance, and may have been Clarence Brown’s final performance before a live audience.

It’s not clear that Brown came outside much during his senior year, as he worked on his thesis, “The Economy and Power Distribution Test of Plant No. 2, Brookside Cotton Mills.” It’s pretty dry reading, but its intent, still urgently relevant more than a century later, was to reduce air pollution. Brown concluded, “By carefully attending to the firing of the Hawley furnaces, practically smokeless combustion can be obtained.” Surely his father took an interest in his conclusions, perhaps hoping Clarence would follow him into the family business. And in fact, one initiative Larkin Brown should be remembered for is his effort, revealed the year after Clarence’s graduation, to drastically reduce the emissions from his plant’s famous smokestack.

Commencements were often held downtown, at Staub’s Theatre, but in 1910, UT chose to keep it on campus, in the Pine Palace, whose ramshackle appearance was disguised with spring floral displays. On the dais were distinguished gentlemen of another era: long-bearded Dr. James Park, of First Presbyterian, was in his late 80s. Prof. Cooper Schmitt, the beloved mathematics professor, also took part; he would die later that year at age 52, after collapsing during a lecture on the Hill.

Clarence Brown graduation photograph, UT Volunteer Yearbook 1910. (University of Tennessee Libraries.)

That day Brown Ayres made the formal announcement of the funded construction of a new Carnegie Library (the steel tycoon-benefactor was still alive and very active then). The announcement was unnecessary except for reasons of formality; the building was already standing, substantially completed but not ready for occupation. It would later be substantially remodeled as the Austin Peay Building, to serve as a main administration building, and later as a psychology department headquarters. Old College, the Civil War-scarred main building, whispering distance from Jefferson Hall, was said to be completely renovated. In fact, it would be torn down a few years later for the construction of much-larger Ayres Hall.

It was said to be the biggest graduating class in UT’s history: a total of 73, though that figure apparently reflects graduate degrees, too. Clarence Brown’s graduating senior class claimed only 44.

For his profile in the 1910 yearbook, the classical quotation chosen for, or perhaps by, Brown, was from Archias, the Syrian-born Greek poet who died in 61 B.C.: “What, fly from love? Vain hope, there’s no retreat / When he has wings and I have only feet.”

Was it an allusion to his relationship with Elizabeth Ayres? Whether it was or not, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that this newly minted engineer had a romantic side.

***

After graduation, Clarence Brown was listed in the 1911 City Directory one last time as a “traveling salesman,” living at his parents large home on East Scott Avenue, on the low ridge above Happy Holler. They had moved there around 1908. It may be interesting, just as an illustration of the fairly diverse city, that their next-door neighbors were Swedish immigrants; August Emil Sjoblom was an engineer for the Southern Railway. Clarence almost certainly knew them. Whether that familiarity helped him get along, in years to come, with another notable Swedish immigrant named Greta Garbo is purely speculative.

It was during Brown’s time at UT that motion-picture theaters began proliferating in downtown Knoxville, especially along Gay Street. Knoxville was by several accounts an early adapter to the new technology, and films were occasionally shown in vaudeville houses, in the larger brothels, and outdoors in parks, even before the Browns arrived in town.

By the time Brown was a senior at UT, Knoxville had at least five dedicated movie theaters, most of them on Gay Street. They showed mainly very short films: comedies, novelties, and brief spectacles. Among the one-reel silent movies that came out in 1910 were the first-ever versions of Frankenstein and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, each of them less than 20 minutes long. It probably didn’t seem like much of a way to make a living. The feature film was yet to come.

The Bijou Theatre, mainly a live-entertainment theater that soon began showing movies, too, opened during Brown’s junior year. Often Gay Street stages in Brown’s youth would feature live performers who would later be cast in Hollywood films, including some by Clarence Brown—among them Lionel Barrymore and Wallace Beery.

Was he there that fall of 1910, when the old Cal Johnson racetrack on the east side of town hosted the region’s first airplane landing? It was part of the first Appalachian Exposition, which featured impressionist artists from around the country, a large pavilion devoted to African American achievement, exhibits outlining new ideas in conservation, and a visit from Teddy Roosevelt.

In 1911, Clarence Brown was listed living with his parents, but working as a “traveling salesman.” But following his engineer’s fascination with automobiles, Brown left his parents’ home on Scott and went north to Illinois to work for the Moline Automobile Co., then back to small-town Massachusetts to work for a more-famous automobile manufacturer, Stevens-Duryea. He learned enough to start his own business, and by age 23 had opened a car dealership in Birmingham. There, by his vague memories, he became more fascinated with the burgeoning motion-picture industry, and moved to Fort Lee, N.J., where several French-born filmmakers were helping invent an industry. By some murky accounts, Brown used his juvenile acting chops to get attention, but he would eventually associate himself with auteur Maurice Tourneur.

After an intermission called World War I—at which Brown predictably gravitated toward aviation, and became an Army flight instructor—he migrated with Tourneur to the new place on the West Coast called Hollywood.

***

In an unusual circumstance, father and son, though a quarter century apart in age, seem to have worked hard and risen rapidly in their chosen professions, blooming at about the same time.

A rank stranger when he arrived in town, Larkin Brown lived in Knoxville almost a quarter century—longer than he ever lived anywhere else—and after a quiet start was emerging as a very public figure in Knoxville about the time his son graduated from UT. The father developed a reputation as a forward-thinking industrialist and Knoxville booster, with imaginative ideas that included cooperation between businessmen, engineers, and educators.

Specifically, he promoted air-pollution controls. In 1911, the year his son left town, Larkin Brown announced the installation of “smoke preventatives” in the impressively tall smokestack of Brookside, claiming they could reduce 90 percent of the soot previously emitted. Again, it was just about a year after his son had made proposals in that regard in his UT thesis.

By 1915, sometimes helping organize big events, sometimes as an after-dinner speaker, Larkin was becoming one of Knoxville’s movers and shakers, both in his leadership of one of the city’s proudest factories, but more broadly in public life, through leadership in multiple charities and civic institutions. He was a powerful man with ideas.

Larkin Brown was a member of leadership committees and pushed for better schools in industrial areas of town. He was a featured speaker at the opening of Beaumont School—true to his holistic approach to industry, he believed that public school up on the hill would be relevant to the future of his Brookside Mill.

Larkin was inducted into the Board of Governors of the Southern Trade Association in 1917, and then led local fundraising efforts for the Red Cross during World War I. He became a stockholder in the New Imperial Hotel Co., which eventually built the Farragut Hotel. He joined the Knoxville Automobile Club, supporting better roads, and was selected to be part of the Board of Commerce Good Roads Committee. He was part of a Teddy Roosevelt Memorial Organization, after that locally popular former president’s death in 1919.

Perhaps reflecting his interests in town, and the fact that they had a car and he could drive to work—a 12-cylinder Packard, in fact—the Browns moved into a stylish home in Maplehurst, in the southwest corner of downtown, in 1919. (By 1920, he was driving a Peerless.) The budding director apparently got to know the place well; in the future, perhaps reflecting extended visits with his parents, Clarence Brown claimed to have lived in that house on West Hill.

Larkin pushed for Knoxville to build a civic auditorium, more than 40 years before it came to be. He tried to organize a much more organized electrical supply for East Tennessee, through an Electric Power Campaign, more than a decade before TVA; he and his wife joined a party reviewing Alcoa’s first hydroelectric dams.

But by then, Catherine Brown was beginning to spend more time on extended trips out to California to visit her son, sometimes for months at a time. Her son had a daughter; a grandchild is likely more interesting to any new grandmother than any of her husband’s ambitious civic ventures.

When vice-presidential nominee Calvin Coolidge came to town on the Southern train to speak at the Bijou and the Market Hall in October, 1920, Larkin Brown was on the Reception Committee to welcome the future president to Knoxville.

***

At about the same time, his son Clarence Brown was directing, originally as a substitute for the ailing Maurice Tourneur, Last of the Mohicans, one of the great feature films of the silent era.

Unlike many in industrial management at the time, Larkin Brown publicly supported the union, and tried to keep the lines open with workers and their concerns. Fortunately, Brookside was doing so well for much of his era that he enjoyed the public announcements of substantial raises. However, when an industrial downturn forced a steep wage reduction, the general manager of Brookside faced some difficulty in April, 1921, when Brookside faced its first strike. He appears to have acquitted himself well, acknowledging both sides in public discussions.

By 1924, Clarence Brown had become famous again in his hometown. Acknowledging his local origins, the Journal & Tribune hailed his 1924 silent feature, Smouldering Fires. “As director of this masterly photoplay, Mr. Brown has won unstinting praise.” For him, it was a “distinct triumph” that “thrusts him upward into the sparse ranks of the directorial geniuses.” It opened at the Strand, on Gay Street near Wall, in May, 1925. (James Agee, then a student at Knoxville High, would become a thoughtful film critic with an unusual appreciation for the artistic value of the old silents; in the 1940s, he would extol Smouldering Fires as one of Brown’s masterpieces.) The murder melodrama The Goose Woman opened a few months later at the Queen, a larger theater, and was lauded in the local press.

The director from Knoxville enjoyed several triumphs that year, including The Eagle, a sometimes comical romantic adventure with Rudolph Valentino. (Hailed as signaling Valentino’s comeback, it was also one of the legendary romantic star’s last films; he died unexpectedly the following year.)

The young director—he was just 35—was doing so well for himself in Hollywood that he offered his parents a more luxurious place in Los Angeles to be closer to him. Nearing retirement age, Larkin and his wife left town in early 1926, about the time The Eagle opened at the Riviera, Knoxville’s biggest theater.

The Browns rarely if ever returned. Larkin Brown was forgotten in Knoxville.

When Larkin Brown died in L.A. in 1942, it’s not clear that Knoxville ever heard the news—nor when his widow, Clarence’s mother, Catherine, died about 12 years later.

***

Meanwhile, beloved teacher Laura Fogelsong’s life and career ended. She had died suddenly and prematurely, at age 52, after collapsing at graduation exercises at Knoxville High on the last day of May, 1928. Her son, Royal, had just received his diploma. It was presumed that the excitement of the occasion was enough to cause her heart attack, but she had other stresses, too; a close associate of her husband’s at the bank had recently shot himself, when it was soon to be revealed that the suicide had been embezzling funds from the Knoxville Savings and Loan. There was plenty of stress to go around.

The News-Sentinel mentioned that one of her students had been the Hollywood director Clarence Brown. At that time, he was working closely with Greta Garbo, with a major movie called A Woman of Affairs. Whether he heard the news about Laura Fogelsong’s death may be hard to be sure about.

***

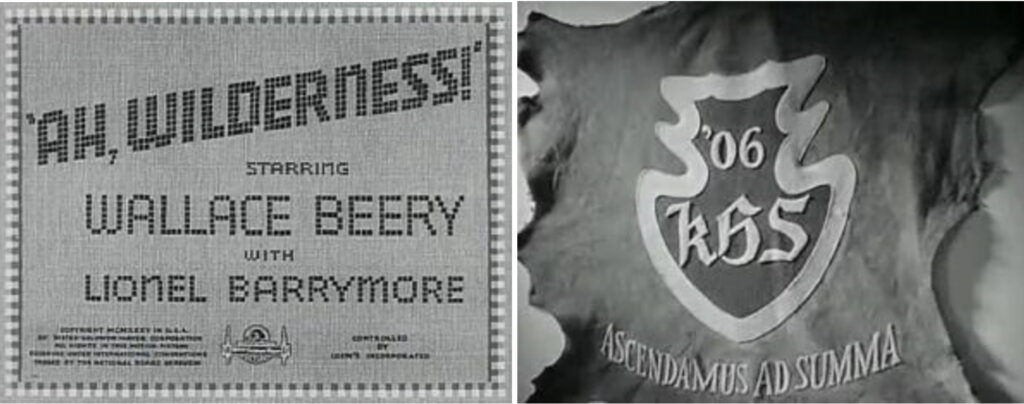

Knoxville is never more conspicuous in Brown’s work than in one film called Ah, Wilderness! Based on Eugene O’Neill’s play of the same name, the dour New England playwright’s only comedy, the movie touted prominently as “Clarence Brown’s Production,” was a 1935 hit, featuring Wallace Beery, Lionel Barrymore, and a new talent named Mickey Rooney. It was shot not in a Hollywood back lot nor in O’Neill’s original small-town Connecticut setting, but at Brown’s original hometown of Clinton and especially nearby Grafton, Massachusetts. However, much of the action centers around characters of high-school age, the age Brown was when he lived in Knoxville.

So though the shooting was done near his early-childhood home in New England, many of his deliberate allusions in the film were to Knoxville. The movie opens with an old Knoxville High School (“KHS”) banner, with its Latin motto, “Ascendamus ad Summa” and several more, from other class years, appear in other settings, like Easter eggs. Part of the KHS Class of 1905 song is sung, word for word, in the film.

Knoxville chums recognized the high-school interior, as that of the original Knoxville High School on Union Avenue, representing the third-floor assembly area. Everything was exactly as it was, they said, down to the placement of furniture, pianos, and statuary, including a model of the Venus de Milo. By the time the movie had been made, the school building had already been destroyed in a 1925 fire, to be replaced with what we now know as the Daylight Building.

Moreover, Brown added minor characters to O’Neill’s original script that his old KHS chums recognized as people they knew. And several of them are on stage, performing recitations, and comically badly. Local sources stated, as if it was a matter of fact, that the kid who recited Poe’s “The Bells” was Clarence Brown’s tribute to himself of 30 years before.

It may be his most personal film.

Four years later, Brown made the much more serious and technically unusual film, with a plague setting in India, The Rains Came, the first film to win an Oscar for Special Effects. Starring Myrna Loy and Tyrone Power, it was new, and recently declared by Knoxville attorney and politician Harley Fowler to be a greater achievement than Gone with the Wind, when Brown returned to Knoxville in October, 1939, for the first time in almost 15 years. The occasion was a gala Homecoming weekend, when UT was playing #8 Alabama. The 49-year-old Brown, who followed UT football closely in California, had publicly predicted UT would win by two touchdowns; Major Neyland’s team won by three touchdowns, later to finish the regular season without even being scored upon, the last team ever to achieve that distinction in NCAA history. A guest at the Melrose Place home of Standard Knitting Mill owner E.J. McMillan, a former UT classmate, Brown attended events at Bleak House (the Civil War relic was then the Lotspeich home, 20 years before it was associated with memorializing the Confederacy) and Cherokee Country Club, and took tours of new Norris Dam and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which was barely an idea when he last visited: “an unknown wilderness in Mr. Brown’s day here,” the News-Sentinel remarked, the Smokies were entirely new to him.

Brown declared that the Knoxville area was the “most picturesque section in the nation,” but remarked at how much his hometown had changed, with a big new post office and multiple viaducts.

It apparently inspired Brown to reconnect with his inner Vol fan. He invited Coach Robert Neyland and his Vols to his ranch for the Rose Bowl a few months later, and again five years later. Then he settled into life in California, and the natural end of his career, making several more important films, including Intruder in the Dust, a Faulkner treatment that impressed Faulkner himself, an extraordinary film with a civil-rights theme, with a speaking role for an important Black character. Brown was a Southerner, born in the 19th century and pushing 60 in 1949, but was still pushing the boundaries.

Always a paradox, he was considered a political conservative, but was credited with a daring antiwar movie (Idiot’s Delight, 1939), and Intruder, which was too controversial for many American markets and reportedly suppressed in Hollywood, but it won the British Academy Award for Best Picture.

He made a few more movies, including the loony original version of Angels in the Outfield, which rewarded MGM with a lawsuit for defamation of character from the manager of the beleaguered Pittsburgh Pirates, who happened to be a Knoxville public-school contemporary of Brown’s named Billy Meyer. But with more money than he could ever spend on himself, and apparently tired of the business, Brown retired at 62 to enjoy a retirement of flying airplanes and driving fast cars. Most of Knoxville forgot about him, until he turned up at a UT alumni party in Los Angeles about 15 years later, leading to the reconnection with his alma mater that resulted in Clarence Brown Theatre.

Brown would offer a major gift of unprecedented proportions to UT, even if the campus as he found it in the late 1960s bore little resemblance to the compact but philosophically diverse and high-achieving college he had known half a century earlier.

Today, the engineering department is very far away from Clarence Brown Theatre, and the well-endowed dramatic department. It would be a freakish rarity for someone to double-majors in engineering and drama. But in Clarence Brown’s unusual mind, the two were adjacent, and sometimes the same thing.

By Jack Neely, August 2023

Leave a reply