WHAT REALLY HAPPENED HERE IN THE SUMMER OF 1937?

It’s July, and it’s hot. Don’t you wish there were a place nearby where you could buy some cold beer and then take your clothes off and dance in the woods?

As U.S. Congress learned through testimony during the era of anxiety over alleged UnAmerican activity, there was a place just like that in our neighborhood, about 86 years ago. It was called Reeves’ Roost. It was on the fringe of Fountain City, on the southeastern side, near the intersection of Beverly and Greenway. For a few days, the whole nation was talking about it.

It’s a tiny episode in the surprisingly large, dramatic, and extremely complicated story of the Communist Party in Knoxville—but it’s perhaps the most vivid. Of all the Communist activity in Knoxville in the 1930s, it was the nude dancing that made national headlines. And that may require some background.

We think of Communist infiltration, real or imagined, as a postwar thing, of the era of Alger Hiss and Joe McCarthy, but Knoxville had several brushes with Communism as early as 1932, when the newly conservative Knoxville Journal alleged there was a “small army of Communists now quartered in the city,” and a woman named Ruth Decker rented space in Sicilian immigrant Mike Armetta’s former Sullivan’s Saloon space, only briefly, before she was revealed to be publishing Communist propaganda. She was free to do so, but Armetta, who’d gone to great lengths to become American, didn’t want anybody subversive in his building, so he evicted her. She found another place in a rental house a few blocks away—only to be trashed by nocturnal vandals a few weeks later.

And there were rumors about Reds in Roosevelt’s New Deal in its earliest days. “They talk a lot about Communist ‘cells’ in the government, but they don’t seem to be in a position to do any damage, and a great many of them are good workmen making real contributions in their minor jobs.”

That line, a wire reporter’s comment that appeared in the (Republican) Knoxville Journal in March, 1934, seems to describe pre-war America’s pragmatic attitude toward the doctrine. Communism was generally frowned upon, perhaps, but rarely cause for panic. That item wasn’t specifically about the Tennessee Valley Authority, but by the mid-1930s, TVA, which was a bit of a radical concept in itself, recruited progressive-minded specialists and clerks from across the western world. Many were idealists, and among them were some Communist sympathizers.

Bob Marshall, a Forest Service executive and well-known Smokies hiker who, with Knoxville attorney Harvey Broome and others, had recently founded the national Wilderness Society, consulted with TVA here and sometimes gave public talks in Knoxville, most famously opposing the construction of a highway through the Smokies. He was openly a Socialist, and before the decade was over, he would be under investigation by Congress for his ties to Communist-allied organizations. His sudden death, at age 38, obviated further investigation. Today he’s memorialized by the Bob Marshall Wilderness, more than a million acres of federally protected wild land in western Montana.

Laurent Frantz, one of East Tennessee’s most radical figures in the 1930s, actually grew up in in Knoxville, as the son of UT language professor Frank Flavius Frantz; Laurent was a writer, UT-trained attorney, and sometime News-Sentinel book critic. He had been elected secretary of Tennessee’s Socialist Party in 1935, and a few months later hosted a public lecture at Market Square by Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party presidential candidate who was by then recommending cooperation with Communists. (Thomas wasn’t the first Socialist to speak on Market Square; in fact, 1936, the Socialist Party ran a candidate for state legislature who garnered more than 2,000 votes in Knox County. Prewar Knoxville seems more liberal than 21st-century Knoxville.) Frantz was arrested in Memphis in 1937 as a Communist organizer, not for the last time. He left a younger brother in Knoxville, John Frantz, who would find himself in the extremist political weather here.

There was also anxiety about the Highlander Center, the labor-activism educational facility led by former and future Knoxvillian Myles Horton down in Monteagle. Among those likely to react, Highlander was often termed a “Communist School.” Progressive Knoxvillians found that political opponents liked to link them to Highlander. Many progressives acknowledged that connection proudly, including a few of the alleged Knoxville Communists of the 1930s.

It was in the summer of 1937 that something started happening here in more specific and obvious ways.

They gathered for meetings all over town: downtown, near UT, North Knoxville, East Knoxville, and up in Fountain City. We can thank the FBI and its hundreds of pages of investigation and testimony for the fact that we have addresses for almost everything. We wish live country music of that same era had been just as interesting to the G-men; it’s not nearly as well documented as Communism is. Knoxville Communism, in fact, could be the subject of a rather extensive driving tour.

Maybe we can’t believe everything people would later say about goings on in Knoxville that summer, but it appears clear that there were a significant number of Knoxvillians who were calling themselves Communists—dozens, at least—and encouraging others to join up.

Communism wasn’t as tough a sell here as you might guess. In the context of the Great Depression, a horror for millions of families, many Americans were questioning some of the basics of how things really worked here. When things get desperate, everything’s on the table.

By 1937, many more were also concerned about the Nazis, as newspaper reports of the Spanish Civil War detailed the outrages of the Nazi-allied Spanish fascists against civilians. Their leftist opponents seemed the best chance for stopping the fascist takeover. Many Americans were happy to support these particular Communists—preferring to call them “Republicans”—some even by going over and fighting in the famous Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In Knoxville, the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy supported all that, attracting more than 200 locals, including a former mayor, a TVA chairman, city councilmen, and prominent businessmen. They met openly in prominent places like the Andrew Johnson Hotel, the Riviera Theatre, and the S&W Cafeteria, to watch films and hear lectures about conditions over there, emphasizing medical needs.

Later, and for many years in the future, national conservative idealogues would denounce that same Committee, in retrospect, as a “Communist Front.”

That summer of 1937, most of what happened behind closed doors—or, occasionally, out in the woods— got little attention at the time. It wouldn’t be discussed in public until years later, but when it was, it sometimes made national news.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, a whole new kind of organization, was exciting to progressives all over the western world, and in the 1930s, they were hiring. Hundreds of experts in forestry, conservation, hydraulics, architecture, art, and engineering came to Knoxville to be part of this massive project to reinvent a troubled valley with improvements in flood control and land management. Helping the experts were more hundreds of college-educated young people just starting their careers, not sure where they were bound. It was an exciting prospect, and the sooty, run-down old city of Knoxville, which had legalized beer but not wine or cocktails, was a weird but exciting place, where jazz bands were on the radio, in the theaters, at the dances, but a young fiddler named Roy Acuff was suddenly getting attention for his brash, outlandish performances of hillbilly music. Meanwhile, George Dempster was marketing his brand-new invention, the Dumpster, and Major Robert Neyland was applying a strange new defense-centric approach to college football, with astonishing success. Their Knoxville was racially segregated, arguably more so than it had been a generation earlier, and hundreds of poor people of both races lived in shanties and rickety boats along the river.

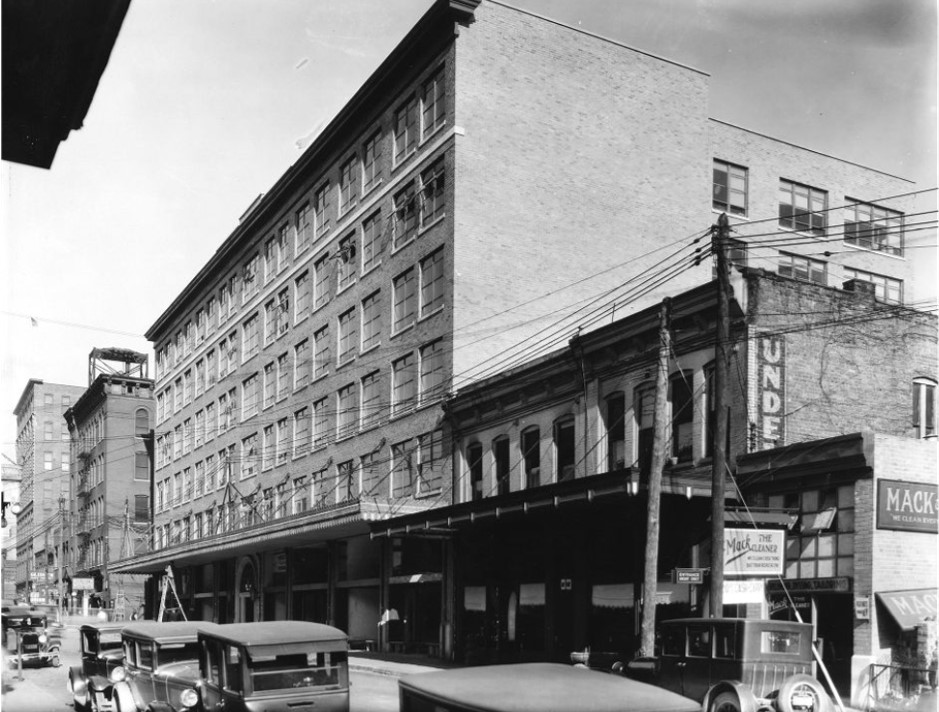

TVA’s world headquarters was on Union Avenue, where the big building later known as the Pembroke was the command center, hosting the offices of Arthur Morgan, Harcourt Morgan, David Lilienthal, and several other geniuses and idealists, where a better life for a multi-state region through careful planning seemed a realistic goal—even if diagonally across Union Avenue was the Roxy Theatre, where rats scurried beneath little boys’ feet, subsisting on cowboy-movie popcorn, as later the same day in the same room a bawdy clown would hand out pornography and introduce aging strippers.

Nearby, the stylish Daylight Building was where engineers rolled out blueprints, as down the street the Arnstein hosted more offices, including those of famous conservationists like Benton McKaye, already a legend as founder of the Appalachian Trail, who in Knoxville started an open and wide-ranging discussion group called the Philosopher’s Club. The fact that the Smoky Mountains, site of the nation’s newest national park, was nearby was part of the appeal. And many of the young people who moved to Knoxville from New York or Milwaukee or Chicago to work for TVA became, for the first time in their lives, hikers.

Many of the male employees with few needs found accommodations at the YMCA at Clinch and Locust; other newcomers found cheap rooms at downtown boarding houses, or at the old Park Hotel, just across Walnut Street from TVA’s headquarters, the same hotel where prostitutes catered to men already perhaps already inspired by the burlesque shows at the Roxy.

Among the thousands who walked the sidewalks of Union were a singular group of TVA’s youngest employees, footloose kids loping around the old town together at lunchtime and in the evenings, discussing new ideas about design, about economy, about what was wrong with the world and how they were going to make it right. They were smart, idealistic, enthusiastic, arrogant, self-righteous, perhaps naïve, and having the time of their lives.

People outside their circle would later remark that they “exhibited a certain clannishness” and “constantly associated with each other.”

The Communists of 1937 didn’t host publicized banquets at the S&W, but they didn’t do much to hide themselves, either.

That particular cadre later came to be of great interest to the FBI, even to J. Edgar Hoover himself, who referred to them as a “Communist cell.” They came to be known to some later scholars as “the Knoxville Fifteen.”

It’s hard to tell exactly where it started. A lively, well-traveled Kansan named Kit Buckles had come to Knoxville in 1935 at age 28, got a job with the big New Deal agency as a stenographer, and would be remembered by an activist colleague as “the original woman Communist of the TVA.” She had developed a broad range of literary connections; a former staffer at Scribner’s in New York, she had helped organize the League of American Writers, working with Lewis Mumford, Van Wyck Brooks, Archibald MacLeish, and other important thinkers of the era. In Knoxville, she worked as an editor for the Knox Labor News, joined the Smoky Mountain Hiking Club, and became a good friend of Benton MacKaye, a regular in his Philosophers’ Club.

Soon one Kenneth McConnell, a former California activist, came to the city with his Asheville-born wife, Elizabeth Winston, as an organizer for the CIO. A former activist in Chapel Hill, McConnell was later revealed to be a formal organizer for the Communist Party. He went by a few aliases, including Kenneth Malcolm, and the perhaps too-conspicuous “Kenroy Malcombre.” Both members of the Communist Party, the couple moved into a house at 1412 Forest Avenue—in Fort Sanders, naturally. (Not much to see there today; capitalism has triumphed, and the ostensible birthplace of the Communist Party in Knoxville is now a parking lot for a cheap apartment building.)

In early 1937, they hosted a picnic at Tyson Park where they invited workers from TVA and Alcoa and extolled the promise of Communism.

Most of their eager first members were in their 20s, and as you might expect, they fell in and out of love with ideals and systems and heroes and sometimes each other. And youngest, most energetic one, the one who would eventually get the most attention from law enforcement, was the one who suffered the most tragic end.

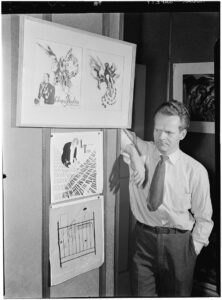

When he got a job as a messenger for TVA, William Remington, of New York, was a teenager. Only 18 when he arrived in Knoxville, a Dartmouth student on indefinite leave, he was notable for riding a motorcycle from meeting to rally. A TVA staffer later described him as “shaggy, sloppily dressed, emotionally unstable, and somewhat uncouth.” To others, the same Remington was a smart, energetic, charismatic shaman. TVA artist David Stone Martin, a close friend, described him realistically: “an intelligent, vehement, and impressionable young man.”

Arriving in the summer of 1936, he got a room at the YMCA with an older Vanderbilt alum, a child of missionaries in India, Henry Hart.

They were often together over the next year, soon moving into a boarding house on Temple Avenue. It was not part of UT’s campus then, but their home was near where Andy Holt intersects with Volunteer Boulevard. Their landlady got suspicious of them as political radicals, and in fact they both joined the Communist Party about that time. After an eviction, Remington and others lived in a converted garage behind the boarding house of Ruby Cox, at 933 N. Broadway. Though it’s gone today, it’s very close to the new restaurant called Ale Rae Grill. Remington worried more than one Knoxville landlady, but some seem to have found him strangely sympathetic.

He seems to have ridden his motorcycle all over town in 1937. His undemanding job and lack of family connections left him time to get involved in several labor and political organizations, including the Communist Party.

It had a regular presence here by early 1937, when McConnell got the order to organize a chapter of sorts in Knoxville, with TVA, workers at Alcoa, and perhaps textile labor organizers.

Alcoa was particularly vulnerable to labor unrest. That July 7, a strike at the plant 15 miles south of Knoxville, involving confrontations between demonstrators and law enforcement, resulted in violence. Both sides brandished guns, and when the inevitable shooting erupted, reportedly 19 to 31, depending on the source, were hit by gunfire. Two were shot to death: one striker Henson Klick, the other Deputy W.M. Hunt. News-Sentinel reporter John Moutoux, who had a reputation for liberal sympathies, was arrested for “inciting to riot.” Popular columnist Bert Vincent was injured later the same day when a guard slugged him with a blackjack.

It ended when the governor called in the National Guard, armed with machine guns. It’s not obvious whether the Communist newcomers were involved in this unusually violent strike, but some conservatives blamed subversives for it.

***

Factory owners found reason to worry about whether outsiders were provoking some of the unrest.

In the summer of 1937, it was not that hard to spy on people. Air-conditioning was something known mainly in movie theaters. Everybody else just left their windows open and turned on a fan.

On those warm nights, a sometime sheriff’s deputy, did a lot of hiding in the woods and outside open windows. On the far side of middle age, apparently in his mid-60s at the time, Josephus S. Remine, known familiarly as “Seph,” was also a livestock and lumber man who’d been elected to the state legislature back in the early 1920s. He wasn’t well remembered outside of Knox County political circles, but a decade later, he’d be making national headlines for what he observed here that hot summer.

Before Congress Remine would state that he was working for the “high sheriff” of Knox County. Though rarely mentioned by name then, that was J. Carroll Cate. A World War I veteran, back on the night of the horrific race riot of 1919 Cate had been the jailer who had tried in vain to stop the armed lynch mob from destroying the jail. Roy Lotspeich, from rural Greene County, was president of Appalachian Mills and publisher of the conservative Knoxville Journal, and was concerned about unruly labor action in association with textile-mill demonstrations and strikes. He persuaded Cate to put somebody on the case.

Remine acknowledged that it all started with an investigation into violence during a strike at Brookside Mills, on the north side of town near Baxter Avenue. A fight had broken out between millworkers and picketers, some of whom were labor activists later identified as young Communists.

Union actions were the original concern. Remine started tracking union leaders with meetings of the Congress of Industrial Organizations—the CIO—and found something else.

The old man had a real challenge keeping up with Knoxville’s Communists. They were all over the place. Remine was spying on them in a place on Gay Street at Vine when they shifted to a rented the fraternal Woodmen of the World hall down the street.

Some of those meetings were at the home of artist David Stone Martin, at 3006 Wimpole Street. The shifting numbering there makes it hard to identify which of the modest-sized houses on that street might be the one, but none of them could have comfortably held many more than a couple dozen people. It’s very near where the Knoxville Botanical Gardens are today.

Remine peeked in at all those places. “We had a whole lot of Communists in Knoxville,” he told Congress.

***

Altogether, it makes a fascinating story, or collection of stories. A couple of weeks of research into old newspapers and released FBI documents convinced me that this could be a great book—before I discovered it already was. In 2009, scholarly researcher and editor Aaron Purcell published, through UT Press, White Collar Radicals: TVA’s Knoxville Fifteen, the New Deal, and the McCarthy Era. I was embarrassed I hadn’t run across it before last week, but it helped round out my research. I had wondered how you could structure a book about 15 or more people over a period of decades, and he did so with mini-biographies of each of them, updated as eras shifted.

The subtitle, by the way, is just a little misleading. When Joe McCarthy first became a U.S. senator, Knoxville’s Communist era had been over for years. We’d already been there, and had the House Un-American Activities Committee looking at us when McCarthy was still a small-town Wisconsin lawyer. The Knoxville Fifteen could be seen as a prologue to the McCarthy Era.

***

Many or most of them were party members for only a couple of years. Several were disillusioned with the Communist Party’s global standard bearer, Joseph Stalin—especially when he signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany in 1939. It would last less than two years, but Stalin had few American admirers after that. Paul Crouch, a Knoxville Communist organizer who was the Tennessee party’s candidate for U.S. Senate in 1940, later remarked that TVA’s chapter seemed to evaporate after the Stalin-Hitler agreement.

The House Un-American Activities Committee is most infamous in the postwar era of Joe McCarthy and the Blacklist. But HUAC was founded back in 1938, originally known as the Dies Committee, for Texas Rep. Martin Dies. The goal was to investigate, in that globally uncertain era, foreign political infiltration. In 1940, led by Alabama Congressman Joe Starnes, the Dies Committee was looking into whether there was a Knoxville-based Communist “cell” with members who were staffers at TVA.

That June, 1940, witnesses before the Dies Committee alleged that there were 55 Communists in Knox County, most of them in central Knoxville, and several of them employed by TVA.

At one point, investigators were especially interested in five of them who shared the same big p.o. box, number 1692, at the U.S. Post Office on Main Street: Howard Bridgman, an Amherst grad from Massachusetts who had been a young associate of Benton McKaye; Pat Todd, a banker’s son from New York who had studied at the University of Wisconsin and the Sorbonne in Paris; Bernard “Buck” Borah, a 25-year-old from Harriman who had lived and worked in New York, then attended UT and wrote for the college weekly Orange & White, before getting a job at TVA; Arkansas textile-labor organizer Horace Bryan—and William Remington.

***

Muriel Speare, a Mount Holyoke graduate who became a TVA junior clerk-stenographer, admitted she was a member of the Communist Party, and was fired from TVA after her revelations before the HUAC.

She said she got involved with the radical organization partly because she didn’t know anyone in Knoxville, and wanted some social ties. She was the only TVA employee who lost her job directly because of her Communist affiliation.

David Stone Martin, the TVA artist, and John Frantz (brother of frequently accused Communist Laurent Frantz), who worked for TVA’s legal department, were both considered radicals. In spite of close associations with Communists, both consistently denied the allegations that they were party members. Both may have chosen to assert their radicalism in another way when they befriended a fellow TVA staffer, Munich-born modernist architect Alfred Clauss. In 1939, Martin and Frantz were announced as two of the original five partners in Clauss’s aesthetically radical Little Switzerland project in the hills off Chapman Highway. They would have lived in what may have been the first International Style modernist development in America. However, both testified before the Dies Committee in 1940, revealing things about their political associations that may have made them uncomfortable in the organization. Frantz resigned from TVA and moved away, and Martin did so a few months later.

In 1943 came an allegation against Henry C. Hart, the junior research assistant for TVA’s personnel division, who had joined the Communist Party at age 21 about the same time his close friend Remington did, but renounced Communism on his own when he “became more fully aware of the nature of that organization.” After that, TVA didn’t seem to bear him any grudges, and he did good work at the agency, and seemed to be settling in Knoxville for the long term. As Martin and Frantz may have intended, Hart expressed his personal radicalism in another way. He also chose to live in a Clauss-designed house, not in the hilltop enclave Little Switzerland but perhaps more boldly, on a hillside in otherwise conventional Holston Hills.

With a shockingly modernist design that might still seem “futuristic” even today, the Hart House is notable as one of Knoxville’s first modernist International Style houses. Its young owner had just moved in when a damning letter emerged, an alleged revelation about his earlier TVA years. The letter’s veracity was questioned in the ’40s, especially after it disappeared, and at least one historian doubts Hart wrote it. The gist of the letter was that Hart had once maneuvered to have a politically conservative TVA coworker fired, and outlined the situation in a letter to Robert F. Hall, a Communist chief in Birmingham. Weeks after that letter came to light, Hart was rather suddenly drafted into the Army. He served stateside. It was, perhaps, an effective way to keep an eye on him. But he came to be trusted, and was eventually promoted to lieutenant.

By then, most of the young radicals of ’37 had left Knoxville. A few had been nudged out of TVA, a few joined the military, but it sounds like most of them moved on for other opportunities, many of them in government. For all the passion of their countless semi-secret meetings held in a dozen different places in town, it sounds as if they didn’t do much more during that four or five-year period than recruit others of like mind, discuss and advocate new ideas in modest ways, and occasionally help striking workers on the picket line. They were unlikely to have undermined TVA, because by all accounts, they admired their employer and its mission.

The War was a major disruption and distraction for all Americans, and seems to have forced an end to the Knoxville Fifteen’s active years. In 1944, Bernard Borah died in the service, reportedly of a medical condition, in Albuquerque; he was just 32.

William Remington, the wild one, the flamboyant teenage motorcyclist and nude dancer of 1937, finished up at Dartmouth, got into a career-track position in industrial research for a government agency in wartime Washington, got married, and showed signs of settling down as an able bureaucrat with a family. Then he got into more serious trouble.

Things got complicated for him fast when he befriended a woman named Elizabeth Bentley, who turned out to be a Soviet spy. Whether Remington knew that, and how sympathetic he was to the Communist Party after leaving Knoxville, became a national story after 1945, when Bentley turned on the Soviets and became an FBI informant, exposing her former associates, including Remington—who would live the rest of his short life under suspicion of subversive activities as part of a Soviet spy ring.

Many of Remington’s old intellectual chums in Knoxville and their flirtation with dangerous doctrines might have been forgotten if not for the fact that in 1947 David Lilienthal, former TVA chief, became President Harry Truman’s nominee to be the first chairman of the newly created and critically urgent Atomic Energy Commission. The youngest of the first three directors of TVA, Lilienthal was in a position of authority at the time that the FBI’s “Communist cell” was operating in the agency. Lilienthal became the overall chairman of the agency in 1941, overseeing TVA’s busiest five years of major dam-building.

Some people didn’t like him, especially U.S. Sen. Kenneth McKellar. Born in Alabama not long after the Civil War, McKellar had been prominent in West Tennessee politics since 1904, when he’d been a presidential elector, in a season when West Tennessee Democrats were worried about Republican Teddy Roosevelt. By 1947, McKellar was 78, but still worried.

Early 1947 was a different era than it had been a decade previously. As Stalin became more of a threat, and China turned Communist, lawmakers were less likely to dismiss a prior Communist sympathy as a youthful indiscretion. The Soviet Union, a wartime ally, had become something like an empire, a rival for directing the future of Europe, and sometimes an enemy, moreover one that was working on an atomic arsenal.

McKellar was the guy who called in Seph Remine before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee to share the gumshoe’s moonlit memories of the Summer of 1937.

***

When grilled about how he knew the people he was spying on were Communists, the elderly farmer-detective struggled to present a convincing answer. He said vaguely that they had found something incriminating in the trash at Ruby Cox’s boarding house at 933 N. Broadway. William Remington, Horace Bryan, and others were often in conference there. It was a letter from Sen. Robert LaFollette, Jr., founder of the Wisconsin Progressive Party, which sometimes aligned itself with Socialism. By the time of the hearings, though, La Follette was better known as a UN-opposing isolationist. Right-wingers who shared that view might have found that bit of testimony ideologically confusing. But in retrospect, it appears that Remine was at least occasionally correct in his assumptions of Communist affiliation.

All of the Knoxville Fifteen at TVA were white. However, a large number of Knoxville’s party members in 1937—Remine estimated they might have numbered as many as 150, at one meeting—were African American. Few Black members were subject to close investigation, and only a couple were named in public. “They would go in the house [at 933 N. Broadway] and march around, and you couldn’t count them,” Remine reported, “but that was all they was doing, joining the Communist Party.”

In all, at least two dozen Communist gathering places in Knoxville were identified, either privately in FBI documents, or publicly in Congressional hearings. At least two were in Fort Sanders. One was a house a block off Riverside Drive. One was a small house near the Park Theatre on Magnolia. One was on Sevier Avenue. One was at 508 Morgan Street, not far from the Coca-Cola bottling plant. But one place captured the whole nation’s imagination.

Before HUAC, Remine described investigating a “Communist camp out in the east end of Dutch Valley, about five or six miles from the courthouse.” He said you could find it by its big mailbox.

In the late 1930s, Reeve’s Roost, on its wooded hillside on the southeastern side of Fountain City, was known as an outdoor bar and picnic area. It was also the name a small suburban development, with at least a couple of small houses on three-quarter to 1.5-acre plots. Its promoter advertised it as a place with “city conveniences with rural quiet.” The steep woods, though, was difficult to develop, and in fact much of it remains undeveloped today. That steep, wooded hillside near the intersection of Beverly and Greenway appears to be where the beer garden was, with a platform for dancing.

Its proprietor, Jesse W. Reeve, was an eccentric Unitarian from Kansas, a linotype operator for the Knoxville News-Sentinel. But he ran several other small businesses in Knoxville, eventually becoming a specialist in hearing aids. From 1935 to 1941 he ran Reeve’s Roost. Beer was the attraction, when it was still considered a bit of a novelty to drink out in public; it had been legal to purchase and drink beer only since the end of national prohibition in 1933, the same year the New Deal and TVA were founded.

Reeve’s wife, Jeanne, was involved in local labor organization. Scholar Purcell refers to them as “confirmed nudists and Communists,” noting that Jeanne Reeve had in fact run for state representative on the Communist Party ticket. She did lead an unsuccessful effort to enter the Socialist candidate for president on the Knox County ballot in 1936, and ran for state representative the same year, garnering 676 votes. Her party affiliation isn’t listed in obvious published news accounts. It’s worth noting that that same race did include a Socialist candidate, J.C. Anderson, who drew more than 2,000 Knox County votes.

By 1947, Jesse Reeve, recalling the goings on at Reeve’s Roost, was careful about what he said for the record. He acknowledged that some locals whom he considered “liberal-minded” did attend picnics and “wiener roasts” there, but he claimed they kept their clothes on.

“I commenced to investigate,” Remine testified. “They had a platform back up in the woods, back of the house, and they were having nude parties. This fellow Reeve was a nudist. We watched them dance there one night. They all took their clothes off but one little girl, she lived down in the field, and she left and went home.”

An FBI document cites a little more detail: eleven couples “both male and female stripped their clothing naked just like they were when born in the world,” and “gamboled nude.”

At one point Remine said he couldn’t hear any music, which raises questions about how they kept rhythm. At one point, Remine said they were square dancing, but also adding some “modern steps.”

Remine admitted he didn’t recognize everyone there. He did identify Remington, who was not quite 20 at the time; Pat Todd; “Buck” Borah; and Horace Bryan.

Remine was careful not to say anything bad about TVA. “It’s pretty hard to get a big organization like that without getting Communists,” he told the congressmen, perhaps aware that the lawmakers had some influence on funding it. “It’s brought millions to our county, and we are proud of it. I have been through it, and there are lots of mighty nice people there, and they have treated me with courtesy and kindness.”

The 1947 Hearings lasted for more than a month. The chairman of the committee was Republican Sen. Bourke Hickenlooper of Iowa. Much of their deliberations were in private, but that particular testimony was in a public session, and made national headlines, even in the Los Angeles Times. The story of nude Communists at Reeves Roost made it boldly in newspapers across America, sometimes on front pages, in Buffalo, St. Louis, Des Moines, Baltimore, Abilene, Detroit, Omaha.

An AP story remarked that “The white-haired Remine spoke with a broad drawl and produced a lot of explosive laughs from senators and spectators.”

In the end, McKellar failed to appall enough senators with these startling revelations. Lilienthal was approved as chief of the Atomic Energy Commission 50-31, with 14 senators choosing to skip that vote.

***

Meanwhile, Remington was still in serious trouble. Some believed his protestations of innocence, and he impressed a “Loyalty Committee” with his sincerity.

The prosecution had difficulty proving he was guilty of deliberate espionage. Remington was finally convicted of perjury, mainly based on his denial of being a member of the Communist Party, and was sent to a federal pen in Pennsylvania for three years. He was a model prisoner, and nine months before he expected to be released, he found himself on the wrong side of a vengeful prison gang. In November, 1954, three inmates attacked Remington with a brick wrapped in a sock. The prison warden blamed his murder on anti-Communist bias among the perpetrators. The FBI studied it and announced that it was more likely a simple robbery. Remington was only 37.

The same year, President Eisenhower, who had recently dismissed TVA as “creeping socialism,” was nonetheless responsible for nominating its leadership, and was obliged to replace TVA Chairman Gordon Clapp, who had himself been accused of Communist sympathies, with veteran army officer Herbert Vogel. One of the first candidates the president considered would have decisively ended any leftist suspicions: his fellow army general, Robert Neyland. But UT’s retiring football coach responded to the suggestion politely: “You do me a great honor, Ike, but I’d do you irreparable harm because I believe half those sons-of-bitches over there are Communists.”

***

It was a trying time for everyone, those who had renounced Communism more than a decade before, as well as for those who remained strident idealogues for the rest of their lives. Many of us have the luxury of reinventing ourselves before we enter middle age, perhaps several times. It’s a peculiar sort of torture to be in your 40s, perhaps with a profession and a family, to describe exactly what your friends were up to when you were 23, what they were saying and doing, and exactly where, often repeating information you’d given to another subcommittee or another FBI agent a few years ago.

Of all the Fifteen who lived under a cloud of suspicion for subversive activities in the 1940s and ’50s, the happiest epilogue may belong to David Stone Martin, the Chicago-born former TVA muralist who once hosted radical meetings on Wimpole, and who announced his intention to build a modernist house at Little Switzerland. He became a notable illustrator, with a fashionably postwar modernist style. He painted album covers for musicians, especially jazz stars, from Billie Holliday to Lester Young to Oscar Peterson, as well as magazine covers, including several for Time in the ’60s, including depictions of Robert F. Kennedy and George Wallace. He eventually settled in Connecticut, and successfully put the world’s suspicions of his loyalty behind him. He died at 78 and rates a Wikipedia page—but at this writing it does not mention Knoxville, TVA, or the Communist Party. (It may be worth noting that at least three of the Knoxville Fifteen—including Martin; Elizabeth Winston, a.k.a. Betty Todd; and Remington—do have entries in crowd-sourced Wikipedia, but several TVA chairmen, including Clapp and Vogel, who guided the giant agency for 17 years between them, do not.)

The Frantz brothers, John and Laurent, spent most of their lives away. The more radical of the two, older brother Laurent left Knoxville just as the Knoxville Fifteen era was fomenting, and eventually settled in the San Francisco Bay Area where he remained an outspoken critic of capitalism, a lifelong activist whose work often appeared in The Nation magazine. Younger brother John worked in government in the Washington, D.C., area, and in 1961 earned a Distinguished Service award from the U.S. Housing Administration. Occasionally they returned to visit their UT language professor father, who died in 1957, and their mother, who lived in Sequoyah Hills until 1962. The whole family’s memorialized at Highland Memorial Cemetery.

Pat Todd, one of the more dashing radicals of 1937, married to Elizabeth “Betty” Winston—the same Elizabeth Winston who’d arrived in Knoxville as the wife of Communist Party organizer McConnell. She was four years older than Todd, but they hit it off, for a time at least, settling in New York’s Greenwich Village, where she worked as a radio broadcaster—Betty Todd lost her job at CBS in 1950 over allegations of her Communist sympathies—and Pat became involved in the civil-rights movement. But he soon began showing signs of alcohol abuse and mental illness. After a divorce and many years away, much of it in mental institutions and some of it in jails in London and Berlin, he returned to Knoxville in 1975, got a room at the Farragut Hotel, and set it on fire. In early 1976, responding to reports that he had threatened President Gerald Ford, FBI agents found him at the Tavernette, the Clinch Avenue beer joint (it later moved and became known as Marie’s Old Towne Tavern, which still thrives on North Central).

Besides Todd’s strange epilogue, the last members of the Knoxville Fifteen to remain in Knoxville were TVA employee Forrest Benson—one of the oldest members of the cadre, he was in his early 30s when he joined the party—and his wife, Christine Eversole. Both graduates of the University of Colorado and close friends of early organizer Kit Buckles, they fell for each other as Knoxville radicals, and commenced a very long marriage, with children. Trusted by TVA, Benson kept his job in the personnel office there for many years. During the Remington case, he and his wife reluctantly testified concerning their involvement in the Communist Party in 1951. The former activists settled in a simple ranch house Sequoyah Hills, where they followed college football and Christine was involved in the local League of Women Voters and West High School projects.

Henry Hart, after an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy as a second lieutenant, spent much of the rest of his long life at the University of Wisconsin, as a respected scholar of political science. He was still around to discuss his idealistic youth with the Knoxville Fifteen with author Aaron Purcell in 2002 and 2004.

“This little band of committed people … energized each other and gave confidence to each other to try impossible, difficult things,” Hart told Purcell. “We accomplished more than we could have done either as individuals or as people who didn’t have this burning ideological energy. And at the same time, I learned, by hindsight, that this process cost too much. It cost too much because it was a very presumptuous, inadequate ideological engine that we had accepted to drive us.”

Hart died in 2014, just before his 98th birthday, almost forgotten in Knoxville, where he had once caused a stir—though his name has been applied to a particular piece of architecture.

Although it’s been altered a little, the Henry Hart House, as it’s been known for years, is still eye-catching to those driving along suburban Holston Hills Road. Finished in 1943, the year he was accused of Communist connivance and also the year he joined the U.S. Navy, it still looks futuristic after 80 years, a landmark of mid-century modernism.

By Jack Neely, July 2023

Leave a reply