ANCIENT TALES OF OUR SPANISH-SPEAKING POLICE CHIEF ARE AT LEAST PARTLY TRUE

Knoxville has traditionally emphasized its Scots-Irish origins, but when we think of Knoxville’s first century, it’s hard to deny an intriguing thread of the Mediterranean. John Sevier’s ancestors were Spanish. One of Knoxville’s earliest settlers was Jordi Farragut-Mesquida, born and raised on the island of Minorca, Spain; he never learned to speak English well, but we preferred to call him “George.” In early 20th-century novelist Anne Armstrong’s only recently published memoir Of Time and Knoxville we learn of an elegant, mysterious, half-Spanish, Half-Irish character named Don Charles Waring, a prominent Knoxville socialite of the late Victorian era who was born in Spain and claimed to be kin to Spanish nobility.

There’s another story I had never heard until recently. In the lore that sometimes has to stand in for verifiable fact in Knoxville’s murky antebellum era comes a story of an extraordinary policeman—a Town Marshal, as they called him—who was so skilled with a long stick and a thrown brick that he never carried a gun.

Part of the story, as sometimes told near the end of his life, was that in the 1850s, he was Knoxville’s “first chief of police” or even “first policeman.” From what we can learn today, it sounds as if those superlatives were generous interpretations. But he was, at least, a tough and respected cop.

His first name was Christopher. His second name, which he apparently favored, was Columbus. And like many boys by that name, he preferred to be called “Lum.”

His last name, though sometimes spelled in ways that made it sound English, was Carlos.

A rare photograph of him, dimly seen in old newspapers, present a dark-complected man, clean-shaven, serious and intense. People who knew him said he spoke Spanish, and preferred Spanish dishes.

***

Christopher Columbus Carlos

He was a bit of a legend in his own time, the subject of stories, so it’s not surprising that there are some discrepancies about his background. He was born sometime between 1824 and 1828, and either in Blount County, Knox County, or Spain, depending on which source you follow. The details most often cluster around the idea that he was born in 1825 or 1826 in Blount County, near the Little River, to parents who were very recent immigrants.

If so, his parents may likely have been refugees from revolution-torn Spain during the troubled and sometimes oppressive reign of Ferdinand VII, during the Decada Ominosa—the Ominous Decade.

But whether one or both of them were immigrants opens another field of study.

The Journal & Tribune reported in 1900 that the septuagenarian Carlos was born in Blount County “of Spanish parentage.” Later, that “he was born in Blount County in 1825, but his father was a native of Spain.”

The Sentinel stated in 1904 that “his father emigrated to America many years before the war.” The same paper later stated that Carlos himself “was born in Spain and came to this country when an infant, when mother and father first went to Ross’s Landing [Chattanooga] … later moved to Blount County.”

But there’s much about his parents that’s pretty murky. The notorious but often useful crowd-sourced website “Find a Grave,” never indisputable, names a mother for him, but not a father. The fact that his ostensible mother’s maiden name is Carlos, the same name as her son, implies that she either found a guy also named Carlos to marry, or that she wasn’t married at the time of her son’s birth. That website implies the identity of his father is unknown.

If Find a Grave’s volunteer research is on the right track, Carlos may not have been the son of Spanish immigrants—but the great-grandson of a Spanish immigrant named John (or Juan) Carlos, who died in colonial Virginia in 1757.

It’s confirmed via Knoxville sources that there was a local guy named Robert Cole Don Carlos who, in 1821, refused to answer a divorce petition from his wife, Elizabeth. Those could have been C.C. Carlos’s grandparents, a few years before his birth. After that, according to other sources, R.C. Don Carlos settled in Boone County, Mo. Later newspaper sources state that C.C. Carlos’ brother, Lafayette, lived in Boone.

All that seems to be connected somehow. What scant evidence there is about Carlos’s background is complicated, confusing and often contradictory. What we know is that he spoke Spanish, he favored Spanish food, and represented himself as Spanish.

For a fellow who preferred not to talk about his parentage, maybe emphasizing a Spanish heritage offered him a different way of being different.

The prospect that he was illegitimate or orphaned aligns with the fact that he came from Blount County to Knoxville, perhaps alone, as a nine-year-old child, to be apprenticed as a tailor in the shop of one of Knoxville’s leading tailors. Children who became apprentices lived in a version of indentured servitude. A “master” would be assigned by a court officer, and the master’s obligation was to provide food, shelter, and clothing, and to teach his charge to read and write.

Lum Carlos’s Knoxville master bore the crypto-Biblical name of Daniel Lyons. According to a roster of apprentices published as East Tennessee’s Forgotten Children, at the McClung Collection, Carlos was indentured in 1835, to work with Lyons until he was 20. At the time, the town was home to only about 2,000 people, most of whom lived on the little blocks arranged atop the bluff near the river. The same roster notes that his brother, Lafayette, joined him in Lyons’ employ the following year.

Knoxville was just a remnant of its capital days, but there were important people here who may have required some tailoring. During Carlos’s apprenticeship, the most famous Knoxvillian was Hugh Lawson White, the U.S. Senator who was a long-shot nominee for president in 1836. Another former senator, John Williams, had been John Quincy Adams’ ambassador to the Central American Federation, based in Guatemala, about the time Carlos was born. He died in 1837, but it’s possible that he was an early customer, and that he and Carlos swapped some Spanish. Carlos likely knew the humorist George Washington Harris, who was only about 10 years older, and had done time as an apprentice, himself, to his older half-brother, the jeweler Samuel Bell, who became mayor.

Stories that Lum Carlos trained Andrew Johnson, the Greeneville tailor, are far-fetched. Johnson was at least 16 years older than Carlos, and is not known to have spent much of his youth in Knoxville. But the two do seem to have known each other, as Carlos would later tell stories about “the big ideas in Andy’s head.” It’s not unlikely that Johnson might have visited Lyons’ shop, or vice versa.

Despite Knoxville’s size, the city’s tailoring scene was often bitterly contentious. In 1843, Carlos’s boss was engaged in a viciously insulting public spat with another tailor.

If Carlos happened to be Catholic, as were most Spanish-speaking people, there was no Catholic church in town until 1855. In 1843—or 1850—he married a local woman named Margaret Davis, by some accounts a few years older than he was, and through that union may have become associated with the Second Presbyterian Church. If so, maybe his wife returned the cultural favor by learning to speak Spanish, and to cook Spanish dishes.

As an old man in a rapidly growing city of tall buildings, Carlos liked to amuse the disbelieving with stories that he remembered Knoxville when everything north of Clinch Avenue was wild, and you could hunt foxes and possums in the wilds of what only later became Market Square.

His wife bore a child, and they named her Lucy. According to “Find a Grave,” it was his single mother’s name. At some point in the 1850s, when he was around 30, Carlos became a law-enforcement officer. In those days, when Knoxville was home to perhaps 3,000 people, there were only three or four. According to a later newspaper account published during his lifetime, Carlos joined the police “when John Marley was chief”—which places it in the mid-1850s. Marley, a Mexican-American War veteran, became town marshal in early 1855.

In early 1857, according to the contemporary Knoxville Register, Knoxville’s Board of Aldermen appointed four men with police authority. C.C. Carlos was chosen to be “First Marshal,” the title later interpreted as police chief.

The Sentinel would later state in 1911, after Carlos’s death, that “Christopher Carlos was Knoxville’s first chief of police.” Carlos was still alive, in his 70s, when the Journal & Tribune ran a little profile of him.

“Mr. Carlos did not even carry a pistol,” noted the newspaper. “He was regarded as a dead shot with a stone, and when he could not reach a disturber of the peace with his long stick, he would wing him with a brick-bat. He can still beat any man in the city throwing stones.”

In years to come, the Knoxville Sentinel told similar stories. “If he couldn’t get in reach of the wrong-doers with his billie, he would hurl a stone at them … and he proudly boasted that he was a ‘crack shot’ with stones.”

Details about his arrests, other than the heroic method of apprehension, didn’t outlive him. But old folks would tell the stories of Marshal Carlos, just like they told stories about Robin Hood or William Tell.

It was a chaotic time to keep the peace. Between 1855 and 1859, the rhetoric about slavery was getting so heated that secession and even war began to seem inevitable. With the arrival of railroads in 1855, when Carlos was a marshal on duty, the city bloomed industrially and was attracting immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Switzerland. Despite the turbulence, Knoxville tripled in size in the 1850s, and was suddenly a town full of strangers, many of them with foreign accents. At the same time, a new anti-immigrant political movement, the American Party—the Know Nothings—was surging here.

It may be one reason his name is often spelled Carliss, or Carless, or Carlas, during that period. The Knoxville Police Department’s own records don’t refer to Carlos as the city’s first police chief. But their records do refer to a guy named Columbus Carliss, who became a marshal in 1855.

However, using the Spanish spelling, the Knoxville Register announced in January, 1857, that the Board of Aldermen chose C.C. Carlos to be the “First Marshal” of the city in 1857. There was also a second and third, serving at the same time. First Marshal may have been equivalent to a “police chief.” And the “First” in that title, presumably implying he was the highest-ranked lawman, may have been what misled later generations to believe he was the very first ever.

Carlos’s name, by any obvious variation, does not appear in the first City Directory, published in 1859. Perhaps he lived just outside of city limits, maybe it was a clerical omission, or maybe he had already left town. It does list two town marshals, John M. Pesterfield and the man later remembered as Carlos’s immediate successor, Martin B. Bridwell. Pesterfield’s name is remembered today as the first Knoxville policeman to die on the job, in 1862, as the result of an accidental shooting from a dropped Confederate firearm.

The story that circulated in his last years was that Union troops arrested Carlos, either because they regarded him as a Confederate, in one story, or simply that he had declined to enlist, in another. Reportedly, the former policeman ingloriously found himself in a federal prison in Cincinnati, until his old friend Andrew Johnson intervened to have him freed—thence to join the Union Army—company L, 12th Regiment, Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry. He served for three years, some of it in the Indian Wars out west.

He ended up in Missouri for several years, perhaps with his wife, though their daughter apparently stayed in Knoxville. Lucy, at least, was back here 1873, when she married a young lawyer who had work at the U.S. Pension Office.

Carlos’s new son-in-law, W.F. Dowell, was known for his sense of humor, and published funny bits in the papers. But he struck one reporter as a “morose and melancholy-looking man.” After the suicide of his brother, Dowell became “deranged” himself, attempting suicide more than once before he finally succeeded by drowning himself in the river, near the downtown wharves.

His widow, perhaps Carlos’s only child, had two or perhaps three children to raise. His son in law’s suicide, and his daughter’s grief, may have been the practical reason for Carlos’s return to Knoxville, reportedly after 15 years away—likely longer, if any of the Civil War stories are true.

Although later memories would put his return in 1875, the same year as his son in law’s suicide, an item in an early 1878 Daily Tribune remarked that “C.C. Carlos, recently of Missouri, has returned, after an absence of 15 years, and contemplates — permanently in our midst.”

But he was back here by early 1878, and spent the rest of his life here. He became “a familiar figure on the streets.”

Now in his 50s, Carlos seemed no longer a candidate for the growing police force, and returned to the tailoring trade.

He had some bad luck now and then. In 1880 a group of three men, including Will Mabry, stabbed him in the side, over an unremembered dispute. All three were arrested for it. Carlos’s wound was at first believed to be very serious, perhaps fatal, but he recovered in just a few days. Will Mabry, though, was shot to death in a saloon fight on Gay Street the following year, a killing some historians have proposed motivated the Mabry-O’Conner shootout that left all three combatants dead in 1882.

Carlos’s home was down on Front Street, near the Prince Street Wharf—just west of modern-day Calhoun’s. The street that ran by the river wharves was sometimes a rough part of town, but it sounds as if Casa Carlos was a sufficient draw to attract distinguished visitors.

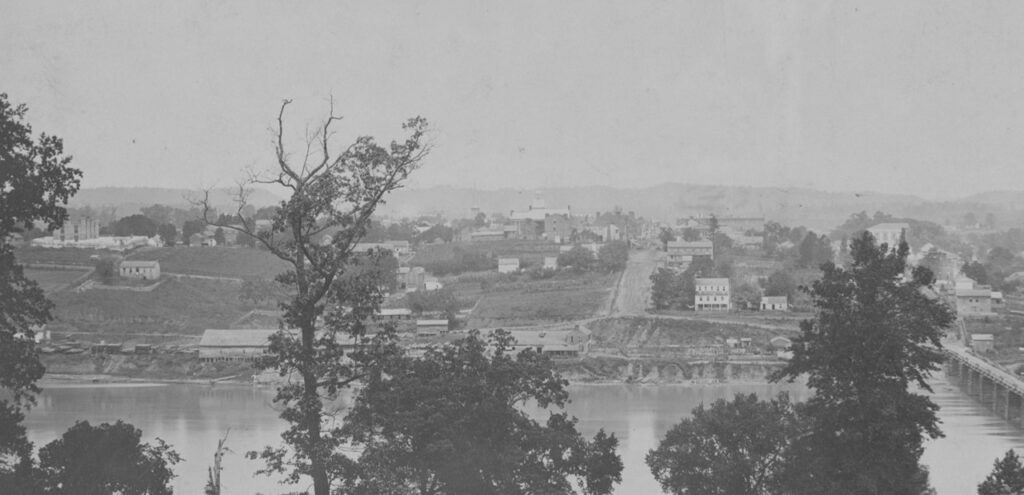

View of the downtown wharves during the Civil War; the old jail is on the far left. (McClung Historical Collection.)

As the Knoxville Sentinel remarked later, “His house was the mecca for the old gentlemen who would gather to talk of the stirring events of the Civil War, and the grand old days when the wily possum and the cunning fox were hunted to their lairs” in what was becoming downtown Knoxville. “Mrs. Carlos would cook the most delectable Spanish dishes, and her table was famed far and near. The Carlos house was a center of hospitality.”

It was just downhill from the old fortress-like jail. In 1885, two law-enforcement officers, perhaps not as adept with a long stick and a rock as Carlos had been, shot a jail escapee dead in front of Carlos’s house. The shots and scream woke his wife up, but apparently didn’t bother him, or tempt the 60-ish tailor to rejoin the boys in blue.

***

In 1904, Carlos was claimed to be the oldest working tailor in Knoxville. It would appear he was often interviewed by young reporters eager for evidence of how much this city of big brick and marble buildings had changed. He was even older than Captain Rule, whose Journal & Tribune reported “Mr. Carlos killed wild ducks where the Market House now stands and chased the festive ‘possum on Summit Hill.”

Carlos had become a Knoxville legend, partly just for living longer than most, in an era when few Knoxvillians remembered the Civil War or anything before it.

Lum Carlos was about 80 when he died in 1906, of pneumonia. He’d seen Knoxville grow from a village of 2,000, accessible mainly by horseback or by very undependable sternwheelers, to a modern city of close to 40,000, with two train stations, an electric streetcar line, and a few automobiles.

His funeral, held at the home of his daughter, Lucy, on East Cumberland, was well-attended. Former Mayor J.C. Luttrell was a pallbearer. Delivering the eulogy was Rev. Robert L. Bachman, well-known pastor of Second Presbyterian.

A Sentinel obituary recalled “In antebellum days, Mr. Carlos was the town marshal of Knoxville when it was but a straggling mountain village, and was always a distinct terror to evil-doers.”

The legend of Marshal Carlos kept swelling in the years just after his death, partly because of the ironic plight of his two survivors. Margaret and Lucy had lived well, and well-protected when he was alive, but by one account, a dishonest evangelist made off with their savings.

The two aging women became something of a cause celebre in the papers, more than once the living symbols of the Sentinel’s annual Empty Stocking Fund, the widow and widowed daughter of the heroic pioneer policeman, living in poverty.

Worse than poverty was the fact that Carlos’ daughter, Lucy Dowell, had never gotten over her husband’s death by suicide. By one account, remembered years later, she had tried to kill herself, too. After her own father’s death, she wound up in a place called Navarre, Missouri. Navarre is a town in northern Spain, but seems hard to find on modern maps of Missouri. But there, according to newspaper reports, she was committed to another asylum, and injected with “a strange potion” that caused her to lose what was left of her sanity. But she wound up back in Knoxville.

After her beloved father’s death, Lucy Carlos Dowell attempted to kill herself.

She was reportedly committed to the “asylum,” in 1909, and appointed a guardian, but she somehow stayed with her elderly mother.

In February, 1910, she tried to drown herself by jumping into the river. She’d chosen too shallow a spot, though, and was rescued by a deaf man, the only witness. Only a few were around to remember that it was about the same spot where her husband had drowned himself, 35 years earlier.

She talked to a reporter, imploring him not to tell her son what happened, but seemed not to care whether it would be published. “I do not know where I am going. Wouldn’t you be nervous, too, if you were in my condition, and had no friends to take care of you, your money all gone, and all you could hear was that you should go to jail or the asylum?”

Less than two weeks later, she tried to drown herself again, at the same spot. This time she was committed to Eastern State, but seems to have spent less than a year there. The stay at the green campus of what was considered a modern, progressive institution seems to have done some temporary good. But her physical realities remained desperate.

In January, 1911, a Sentinel reporter found her and her 87-year-old mother living in “a little room at 912 State Street”—the location of the modern Dwight Kessell Garage.

“Both Mrs. Carlos and Mrs. Dowell speak Spanish,” the Sentinel observed, “and bear themselves in their home with a love and kindliness to each other which shows a good breeding entirely out of place with their surroundings. The sunset of their lives is dimmed by the most abject poverty. They are poor in the world’s goods, but they are rich in a fund of hallowed memories. Their greatest joy is of telling of the husband and father, and the time for Mrs. Carlos to go to him will not for her be a time of dread.”

But it was the younger widow who went first. Just five months after that profile, Lucy Dowell “succumbed after a long illness”—the Journal & Tribune called it “a complication of diseases” at Knoxville General Hospital. According to the Sentinel, “she was the only daughter of C.C. Carlos, the first chief of police of this city. She has always been charitable and kind to all who came in contact with her, and her death is much regretted.”

Margaret Carlos lived on. She was struck by a car, or more precisely, “run over by a lumber wagon,” on Union Avenue, and broke a hip. She was committed to Lincoln Memorial Hospital, a facility then connected to Knoxville’s medical college, where she spent the last six months of her life. She was 93.

In 1911, the Knoxville Sentinel stated that Columbus Carlos “was one of the best known and most highly respected citizens of this city. His name will always be familiar in the annals of East Tennessee and Knoxville.”

That has not been the case.

Jack Neely, June 2023

Leave a reply