SOME AWKWARD LATE-CAREER DRAMA FOR TWO OLD PROS

It’s baseball season, and one of those national movie channels has been showing an old baseball movie that raises an interesting question about the relationship of a couple of once-famous Knoxvillians. After research, it leaves us with an unsettling puzzle about the unexpected consequences of combining two very different kinds of entertainment.

The movie is the original Angels in the Outfield, a lightly bizarre fantasy sports comedy from 1951.

Today, the 1994 remake is probably better remembered, but the original was a minor classic of its era, combining two postwar genre favorites, the baseball comedy and the lighthearted afterlife fantasy. For those who like classic-era baseball, it may be worth watching just for the many baseball scenes, several involving real players, and not all of them involving angels.

Its director and producer, both, was one Knoxville-raised UT grad named Clarence Brown, the son of a Brookside textile-mill manager.

The premise is that the gruff, overbearing manager of the floundering Pittsburgh Pirates makes a deal with heavenly hosts to recruit the spirits of dead ballplayers to help the beleaguered team—if he’ll just stop cussing at everybody and be nice to people.

The movie opens with a note of gratitude to the accommodating courtesy of the real Pittsburgh Pirates:

“Through the kind cooperation of the Pittsburgh Pirates, we have used the team and its ballpark to tell our story….”

It was not filmed on a studio back lot. Brown, who had pioneered location shooting back in the ‘20s, wanted to shoot it at some real big-league ball parks, especially the Pirates’ actual stadium, old Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Nine years later, it would be the site of the Pirates’ dramatic homerun World Series win. But in 1951, Forbes was the oft-forlorn home of a habitually underachieving team.

The manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates at the time the movie was made was named Billy Meyer. Son of a German immigrant who became a well-known Knoxville beer brewer, Meyer was born and raised here, on the northwest corner of downtown, in Mechanicsville, near the biggest brewery in East Tennessee.

That connection, the Hollywood director and the Pirates manager who helped with the movie, had never occurred to me before last month, when I watched the movie for the first time. These two major figures in the story were both from Knoxville. Could that be a coincidence?

MGM Director Clarence Brown (University of Tennessee Libraries)

Meyer and Brown were middle-class Knoxville kids, both sons of factory supervisors, both proud Knoxville High School alums. (Clarence Brown was so proud of his alma mater that he used a KHS banner at the opening of one of his best-known movies—even though Ah, Wilderness was set in New England.) The two were less than three years apart, Brown two years and eight months older than Meyer. You’d think they might have known each other here. It’s not clear that they did.

Still, both were standouts at KHS, for whatever it’s worth, in different ways. Both had their names appear in Knoxville papers more than the average public-school kids: Meyer mainly as a very impressive young baseball player, Brown mainly as a performer, especially of dramatic recitations. There’s a good chance they’d at least heard of each other here.

Billy Meyer, who had learned to catch in neighborhood sandlot games around Mechanicsville, where he grew up, first played in public in Chilhowee Park in 1907, when he was a surprise substitution at an insurance convention, a game between married men and bachelors. He was just 15, and barefoot, but his performance was so impressive that when the Bachelors won, they presented him with a pair of socks as a prize. “That was my greatest day in sports,” he would claim decades later, when he was in the big leagues. “I felt then like I’d never want to do anything but play baseball.”

It was the year Knoxville banned saloons, and the promising career he had once imagined, inheriting his father’s brewery, was beginning to seem an even longer shot than pro baseball. Meyer was still a teenager when he took time out of high school to traveling to make some money playing ball with a Florida team when he was only 17. He returned home to play with the Knoxville Reds in 1910 and 1911.

His later association with Clarence Brown gives us cause to remember the spring of 1911. It was the last time the two of them ever lived in the same city.

It was the year when Honus Wagner, Christy Matthewson, and Ty Cobb dominated the sports pages. Especially Ty Cobb, of the Detroit Tigers. He was just 24 that season, but already well known in Knoxville, which was then still mainly a baseball town.

It was the last spring that Brown lived in Knoxville, and the spring that Meyer’s name was in the paper much more than that of most adults.

“Knoxvillians are Glad They Get Billy Meyer,” ran the headline in April, 1911, about an arbitration that left Knoxville’s Appalachian League team with Meyer, who was at age 18 the city’s favorite homegrown ballplayer. He wanted to make a living at baseball, but played every chance he got. Fans watched him playing minor-league ball, but also watched him closely when he played in pick-up teams, like one that played against the UT Vols’ official baseball team. In a game at UT’s Wait Field in April, 1911, described as prominently as most intercollegiate games, the “Pick-Ups,” with Meyer as catcher, beat the Vols on their home turf, Wait Field at the foot of the Hill.

Too small to be a contender in most sports, Clarence Brown, then living with his parents on Scott Avenue, may have read about the baseball phenomenon with interest.

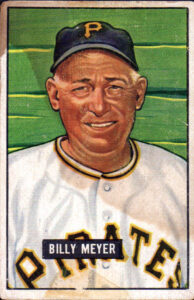

Billy Meyer (1893-1957) from a 1951 Bowman baseball card. (Wikipedia)

Billy Meyer excelled as a catcher in the minor leagues for many years, especially with the Louisville Colonels, and did crack into the majors, with the Chicago White Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics, but never became a star. He became a minor-league manager in 1926, working in Minneapolis, Springfield, Kansas City, Oakland, Newark, winning lots of games and the title of Minor League Manager of the Year.

Just after the war, the New York Yankees offered him the most prominent baseball-team manager job in the country. It wasn’t that surprising; Meyer had been in the Yankees organization for years, and bred some star players, like shortstop Phil Rizzuto. But Meyer, now in his mid-50s, suffered a heart attack that might have seemed the end of his career, if not his life.

However, Meyer another shot at managing in the majors when Pittsburgh hired him in 1948. Fate greeted him with a winning season, as he turned around the Pirates’ losing streak and earned national praise from sportswriters.

But as a big-league manager, Meyer was never able to duplicate the success of that first year.

Meanwhile, working for MGM in Hollywood, Clarence Brown, whose only forays into the world of sports were National Velvet, which involved horse racing, and the car-racing romance To Please a Lady, picked up a Scranton priest’s whimsical story about big-league baseball, and thought it might make a lively screenplay.

To play the Pirates’ manager—Meyer’s role in real life—Brown hired Paul Douglas, who had appeared in a recent baseball hit comedy, It Happens Every Spring. Douglas had a big, classic baseball face.

Brown, who had earned two engineering degrees from UT in 1910, enjoyed technical challenges, and this one presented a few, including one involving audio engineering. In those days when even bleak film noir murder movies allowed no profanity, Brown found a way to scramble actor Paul Douglas’s voice to sound like he was cussing, even if you can’t make any of it out. That innovation is perhaps the strangest thing about the movie—other than pairing Douglas with the much-younger and comparatively tiny Janet Leigh. At 23, she was a relative newcomer in Hollywood.

***

Toward the end of the 1951 baseball season, Angels in the Outfield opened at the Tennessee Theater in September.

A page 17 item in the Sept. 23, 1951, Knoxville Journal suggests the two first met in California in spring, 1950, in preparation for the Angels film. “It took a Hollywood motion picture to bring together two of Knoxville’s most famous citizens of the past,” goes the unsigned article: “Manager Billy Meyer of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who still makes his home here during the off season, and Film Director Clarence Brown.”

Knoxville News-Sentinel, Sept. 23. 1951.

It explains that Brown actually made the arrangements concerning using the Pirates’ name and stadium with major owner Branch Rickey. But the director wanted to be sure Meyer was in the loop. “Admittedly with some hesitation, Brown approached Meyer for a final okay on the picture, [the] main character of which is a surly, profane manager of the Pirates, portrayed by Paul Douglas. Although the character obviously bore no resemblance to the gentle, soft-spoken Meyer, Brown still felt that he should have Meyer’s approval. That came readily after Meyer read the script.”

That paragraph may be a little surprising on a couple of counts. One is that not everybody who worked with Meyer thought of him as soft-spoken. Back in 1948, Norman Rockwell had depicted an intense Meyer in mid-argument in a painting called “Bottom of the Sixth.” It could almost be a scene from the movie.

And there’s maybe a bigger reason for hesitation, perhaps on both sides. In the script, the Pirates are represented as a desperately struggling team wishing for any advantage, even a supernatural one, to maintain competitive credibility. And in fact Meyer’s team was then struggling for credibility in the National League. It may have been unprecedented for a losing team to portray itself as a losing team in a major Hollywood comedy.

Superficially, Paul Douglas who played the embattled manager, and who looked older than 44, did bear a little resemblance to Billy Meyer, both of them grizzled, stocky, graying.

The Journal article adds, “before they parted, Meyer surprised Brown by saying, ‘You know, Clarence, I’ve been trying to catch up with you for 40 years. You were two years ahead of me at Knoxville High. But it took this picture of yours to get us acquainted.” (It’s true that they were less than three years apart in age, but if they were ever that close at school, it was only briefly. A bit of a genius, Brown graduated from KHS at age 15, entering UT as a freshman, when Meyer was only 12.)

Later, during production in Pittsburgh, Brown and Meyer “spent many an hour in happy reminiscences about their time in Knoxville.” Meyer served as an uncredited technical advisor on the film, which includes a good deal of baseball action. Long retired Pirate third baseman Pie Traynor, who was also a predecessor of Meyer as manager, as well as former right fielder Paul Waner appeared in the film. Several of Meyer’s players appear in action on their home field, Forbes Field; Meyer’s team at the time included outfielder Ralph Kiner, whose home run is featured in the film.

It’s a pretty weird movie. Performing cameos were current Yankees star Joe Dimaggio; part owner of the Pirates, Bing Crosby; and the hero of Meyer’s youth, Ty Cobb, the Georgia-born legend of the Detroit Tigers was then in his mid-60s, but made time to say a few words about a semi-fictional baseball team before Brown’s camera.

As it happens, there’s a third Knoxville connection to that movie. One of its speaking parts belongs to Richard Hale, whose severe, flinty countenance stole him scenes in dozens of movies of that era. In Angels, he’s the skeptical psychiatrist Dr. Blane, who tried to explain away the angel phenomenon scientifically. The Rogersville native spent several years of his childhood in Knoxville, as his outspoken mother, Annie Riley Hale, taught at old Girls High School, located in the same Union Avenue building where Clarence Brown, who was two years older than Richard, attended Knoxville High. It’s likely they crossed paths then; both were known as child performers. Hale appeared in at least two Brown productions in Hollywood.

***

As the movie was in production, Billy Meyer was bringing in young catcher Joe Garagiola and veteran hitter George “Catfish” Metkovich to join the Pirates. Bob Friend, the young pitcher who would be a star for the Pirates in their World Series champion year a decade later, was a new hire. One of Meyer’s coaches was the legendary Honus Wagner, who was a Pirates star when Meyer was a boy in Knoxville.

Wikipedia (source: http://www.impawards.com/1951/angels_in_the_outfield.html)

Angels in the Outfield played at the Tennessee that September, 1951, originally announced for three days, a typical run then even for a big movie, it seems to have been sufficiently popular to hold it over for the rest of the week. Perhaps it helped that a few promotions mentioned Clarence Brown’s local origins; if none mentioned Billy Meyer’s behind-the-scenes work, all local sports fans knew that he was manager of the Pirates, and that might have been another reason for a Knoxvillian to buy a ticket.

The movie returned a few weeks later to play at the Tower, the big new suburban theater on North Broadway, then at the Park, on Magnolia, then at the Booth on Cumberland. Then in the small neighborhood theaters. Then, six months after its opening at the Tennessee, it was playing at the “Colored” theaters of still-segregated Knoxville, like the Booker T. And then at the drive-ins out in the country. It was a typical pattern. When it was four years old, Angels was still playing in area drive-ins.

It was popular in the hometown of the director, but it was also popular in the White House. President Dwight Eisenhower had a personal copy, and played it so often on his projector that he told Clarence Brown he had to replace it twice.

***

What happened next is a little perplexing.

The late-blooming Brown-Meyer friendship may have been little more than a scrap for the sportswriters. Meyer’s name does not appear in the thick recent biography, Clarence Brown: Hollywood’s Forgotten Master. According to the newspaper accounts, though, Meyer had read the script, as Brown had requested, approved it, and helped production as a technical advisor for the baseball scenes. He even took part in some promotions for the movie in Pittsburgh. During a Pirates-Reds game at Forbes Field, Meyer posed smiling with Father Richard Grady, the Scranton priest who wrote the original script for the film. Also there in the shot were several involved in making the movie, including Meyer’s Hollywood alter-ego Paul Douglas and Clarence Brown himself. At that occasion, Brown quoted Branch Rickey, Pirates general manager and nationally known baseball promoter: “The story will not only do a great deal for baseball, but will have an uplifting effect on everyone who sees it.”

One eavesdropping reporter overheard Meyer, watching the film about angels helping the hapless Pirates, remark, “Why can’t something like this happen to me?”

Ironically, it was days after that gala event that the first rumors began to circulate in sports columns that Billy Meyer, after another losing season, was on his way out. The following August, despite his reputation as an easygoing manager, a frustrated Meyer was thrown out of a game for arguing too strenuously with an umpire over a wild throw from one of his recent hires, catcher Joe Garagiola.

It turned out to be his last season. Meyer’s team won only 42 of 152 games, one of the worst records in major-league history. He lost his job.

Clarence Brown’s career ended the same year. He made only two movies after Angels, neither of them counted among his best. After over 30 years making motion pictures, he seems to have been content to put show biz behind him. He spent his retirement flying planes and driving fast cars in California, rarely even watching movies.

***

Despite his firing, Meyer and the Pirates management shared a mutual respect. He remained for a couple of seasons as a scout and troubleshooter for the club, often traveling to scout Negro League players. It was during that period that the Pirates hired their first Black player, second baseman Curt Roberts, in early 1954. But early in the 1955 season, while working in North Carolina, Meyer suffered a stroke that left him partly paralyzed on his left side, and by several accounts, also a heart attack—and moved back to his home on Central Avenue Pike in Knoxville, where everybody liked him no matter what.

We might not know about his official opinion of the movie he’d helped with if not for a tax dispute. In October, four months after his stroke, Meyer and his wife filed a lawsuit against the U.S. government that brought attention to an awkward fact not widely known before.

Back in 1951, before he smilingly promoted the movie about his team, alongside the writer, director, and star, Meyer had complained to MGM about the “derogatory” depiction of a miserably contentious Pittsburgh manager as a “rough and unsavory character.” Even before the film was in general release, Billy Meyer sued MGM for damages, claiming it damaged his reputation. MGM paid him $2,500 in damages, which—regardless of unreliable inflation calculators that suggest it was the equivalent of about $30,000—was certainly a much more sizeable sum than it would today.

According to Meyer, the federal government took most of that settlement, apparently regarding it as income on top of his major-league manager’s salary. Meyer considered it to be unfair taxation of a settlement that had nothing to do with earned income.

Why he went public with his complaint four years after the fact may have had something to do with his health. Stroke victims require a lot of care, and often need all the money they can find.

It wasn’t quickly resolved. In early 1957, Meyer was still in the news about dealing with the tax issue concerning MGM’s damages when, at Fort Sanders Hospital, he died, reportedly of a kidney ailment, at age 64.

Within days came a popular proposal to name the still-new baseball stadium at Caswell Park in his honor. It would keep that name until its demolition half a century later.

For whatever it’s worth, actor Paul Douglas, whose problematic portrayal of the Pirates manager was at the heart of the lawsuit, died just two years after Meyer, of a heart attack, at age 52.

Angels in the Outfield was still showing in Knoxville theaters occasionally, as a World Series-time matinee, as late as 1961. Later, WBIR-TV ran the movie several times as Late Shows and Early Shows, always during baseball season.

When Clarence Brown, then long retired from the movies but still living in California, returned to his alma mater to discuss a major donation to found a performing-arts center, Angels was one of four or five movies listed to help Knoxville remember who he was.

By Jack Neely, May 2023

Watch the film’s trailer.

Leave a reply