The Remarkable Story of a Diversified Horseman

To us, Pryor Brown is the name of a parking garage, and of a longstanding dilemma of a large, unusual building that seems to have value but never a developer with the wherewithal to convert it to modern use. Converting old industrial or office buildings to residential or retail use has been the formula for the profitable magic of downtown’s revival over the last 30 years.

The big yellow-brick building at the corner of Market and Church was an unusual parking garage, the old-school sort, with attendants who spent their days scrambling around its four ramp-connected floors, riding its step-on elevators, shuffling cars around to efficiently deliver them to their clients. It was still doing good business until about 10 years ago, when the building’s owner closed it as he proposed demolishing the building to expand the conventional surface lot that surrounds it. It was the beginning of a period of highs and lows for those who saw potential in the building, as one well-heeled developer made plans for purchasing and preserving the building for mixed-use development, but after some months withdrew. Lacking other saviors, the building will likely be torn down in the next few weeks.

It was built in stages between 1925 and 1929, as a mixed-use parking garage, with retail space on its ground floor, and a pioneering model for sensible parking garage construction from the early days of that approach. It was also unusual in that its reinforced concrete and pressed-brick construction made it possible to build a parking garage without pillars and posts to interfere with moving cars around.

Some news from around the country suggests it may be one of the oldest parking garages in America. Perhaps even the oldest. Chicago used to have a garage that made that claim, but it was torn down in 2005. The website “Roadside America” claims that a parking garage in Welch, Va., is America’s oldest—but it was built in 1941—a dozen years after Pryor Brown.

If parking garages are important to urban development, as they certainly seem to be, that may make Pryor Brown an important landmark, and not just regionally.

Some might chortle at the mere suggestion of a historic parking garage, but popular News-Sentinel columnist Bert Vincent once referred to this same building as “the old Church Avenue landmark,” and that was in 1952. It’s 71 years older now.

Pryor Brown is an interesting parking garage, sure enough. But Pryor Brown was also a man.

His name has been associated with that particular intersection for almost 150 years.

***

Pryor Brown was never quite sure of his birthdate, but it was around 1849. He was born to Hugh and Mary Brown, in the Brown’s Mountain community of deep South Knox County, long before it was part of any city. He was related by marriage to William Rule, the beloved editor and sometimes mayor who grew up in the same part of the county.

At age 14, which would have been during the Civil War—presumably during Union occupation—Pryor Brown found work carrying U.S. mail on horseback between Knoxville and Maryville. It was the beginning of a very long association with the U.S. Postal Service.

It was near the then-new post office on Prince Street (now Market), in the late 1870s, that he opened his first livery stable. A little later, with partner Bascom Rule, he moved the operation half a block to this Church Street intersection in 1882.

In those earliest days, the city had no reliable water system; to give his thirsty steeds water, he had to lead them down to the river.

Knoxville Sentinel, July 4, 1910.

He took care of other people’s horses, but within the business of horse-drawn vehicles, he diversified. His “transfer” business was essentially a moving company, if broader in scope than most. He provided help for people who wanted to move luggage and furniture, but also transported bulky stage sets for vaudeville groups from the train station, where they arrived, to the theaters, most of which were half a mile down Gay Street. He established a “Theatrical Transfer” division of his operation.

He transported people, too. Contemporaries claimed that he introduced the idea of the taxicab to the city, before most Americans had ever seen an automobile. Cab is short for cabriole, a style of carriage that he used. He sometimes gave lifts to folks in showbiz, and one he would mention in later years was the already legendary New York actor John Drew, uncle of the Barrymores, who performed at Staub’s Theatre on Gay Street more than once.

Brown contracted to build specialized carriages for multiple purposes. He had carriages built expressly for mail—in the days before the federal government built its own mail trucks, they contracted with locals like Pryor Brown to do the job. Other carriages he built expressly for weddings. Others were hearses, another specialized use for horse power. He owned broughams, cabriolets, hansoms, Victorias, and if you had the money to rent one, you could take your pick.

His two-story livery stable was described as “the most modern in the city.” Brown likely never heard the word “intermodal,” but his livery stable was that, used as a hub for horseback riders, transfer companies, the post office.

They were all part of Pryor Brown’s business, and his passion. He loved horses, which he called “the noblest of animals.”

He took care of other peoples’ horses, and for convenience even hosted a “veterinary hospital” staffed with veterinarians, adjacent to his stables.

At the height of his business, he had 242 horses of his own, employed in his extensive transfer and cab businesses.

Interested in new technology, if sometimes grudgingly, Pryor Brown got a telephone for his business, making it one of the first Knoxville entities to be reachable by Mr. Bell’s invention. Pryor Brown was the 19th, in fact, and 19 was his phone number for some decades.

In 1884, he married Josephine Sullivan at Immaculate Conception, when it was still a small stone church on Gallows Hill, populated mostly by people with Irish accents. The Browns lived in Mechanicsville and had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood.

The livery stable went up in flames in July, 1913. Remarkably, by one account, all 200 horses in the building were saved. Even if a later account alleging that one horse died is true, that’s still an impressive figure, a testament to a man who cared about his horses.

By one account, he once sold a fancy carriage to Henry Ford, for his famous museum. Considering that Ford’s creations forced major changes to the horse business, that may ring of irony.

By one account, Pryor Brown entered the car-parking business unexpectedly in 1915, when a man named Wiley Morgan worried about leaving his new car out in the weather. He talked Brown’s son, Charlie Brown, into letting him stow it in one of his horse stables.

When he heard about it, Pryor Brown was furious. The old horseman demanded that the contraption be moved. “You few fools in this town buying automobiles ought to come back to your senses,” he said, as remembered by Wiley to Bert Vincent 37 years later. “It won’t be no time before you get rid of those fantastic machines. You’ll be wanting a horse then.”

On another occasion, he remarked, “I wouldn’t give the horses I love best for the whole stableful of those cars.”

But with encouragement from his 30-year-old son, Charlie, who served as vice president and manager of the business, Pryor Brown began to accept the inevitable. The era of horsedrawn vehicles was coming to a close. But he learned that he could run the same kind of business with internal-combustion engines that he had once done with horseflesh.

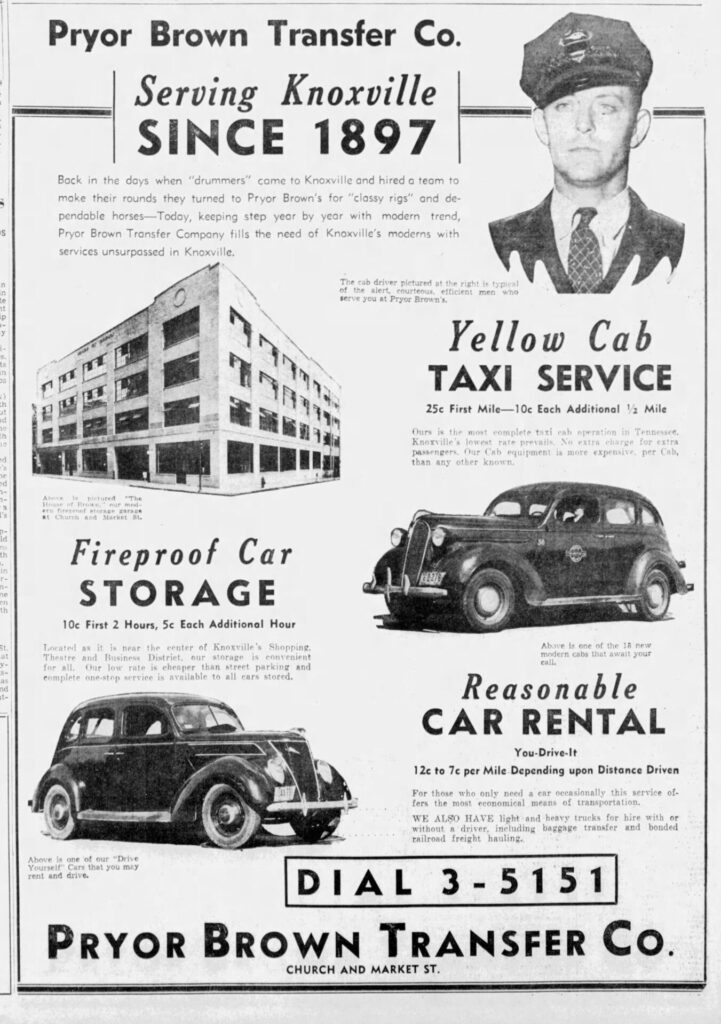

In 1920, Brown purchased a fleet of Dodge automobile taxicabs, and in the Jazz Age, Pryor Brown cabs were a way to get around, even for people who’d never been in a motorcar before. He eventually had two different fleets of cabs, operating the Yellow Cab line becoming known nationwide, and his own “Brown Line Taxi Cabs.”

Soon after that, the Pryor Brown stable shifted to caring more for automobiles than horses. The building at 314-324 Church—whether some part of it survives in the current building has been a matter of speculation—became Knoxville’s largest parking garage.

And from the same building, Pryor Brown also rented automobiles, just as he had once done with horses. For a while, you could get either a horse or a car at Brown’s—or switch from one to the other.

Despite his continuing skepticism of cars in general, Brown proved to be an innovator within that new model of business. Pryor Brown cabs became, in 1923, the first to install trustworthy Ohmer mechanical meters, which printed receipts for the customer. “The machine, it is said, is not subject to the erratic shortcomings of the human brain.”

Brown charged 25 cents per first one-third mile, and 10 cents for each one third thereafter.

Brown also operated a moving company, with an office at the new Farragut Hotel; in 1923, he claimed to have helped 3,000 UT students settle in. By then, he also had staffed branch offices in both railroad stations, the Southern and the L&N.

***

The Browns built the familiar four-story building known as the “House of Brown” in the 1920s. A part of it on the interior of the block was built in 1925, but most of the building we can see today was built in 1929. (It was announced in late 1928, the same week that Ben Sprankle announced the construction of the tall Union Avenue building we now know as the Pembroke.)

It was the first ramp garage in Knoxville, and unusual in that it had no posts or pillars to impede parking cars. It was so unusual that Brown hosted an evening open house to show the unusual new kind of architecture to the public. Upon its completion, it could hold 400 automobiles at a time.

It was a full-service parking garage. Getting your car washed as you left it there was an option, with facilities to wash two cars at a time. The parking palace was claimed, on good authority, to be fireproof.

Rates back then, if you must know, were a Mercury dime for the first two hours, a buffalo nickel for each hour after that.

Pryor Brown Transfer Company, 1936 (Thompson Photograph Collection, McClung Historical Collection)

And it had an oddity. Installed visibly into the new Pryor Brown Garage on the Church Avenue side were two gold bricks, on either side of the front door. Or so it appeared. They were part of an old South Knox County tale that Pryor Brown enjoyed, about a character who purchased land from some mysterious characters in exchange for gold bricks. [See “The Legend of the Gold Bricks,” our story included in the KHP paperback collection of the same name.] It was fodder for at least half a dozen newspaper columns over the years. But the gold bricks weren’t really gold. They were bronze, or brass, or by one telling, just yellow-painted clay bricks. The man who was cheated, a respected farmer named Henry Davenport, didn’t have any desire to keep these bulky shams around, and gave them to his friend, Pryor Brown. Who, as it happens, was happy to have his masons install them in his new parking garage, on either side of the main door, where everyone could see them.

By the time the cement dried, Pryor Brown was pushing 80 years old, but the old horseman still came to work every day, maintaining the corner office at street level. He was still in charge of the place which was only vaguely akin to the livery stable he’d founded there 50 years earlier. He parked cars, but he was also listed as a U.S. Mail Contractor, a taxicab network, and a theatrical-set transfer company, all commanded from these little offices along Church Avenue.

He didn’t mind that pedestrians could look at him in his office; often they’d come in to say hello, and tell a story or hear one.

He could no longer see well enough to read, but his assistants would read documents to him.

On his wall was a horse harness and several framed photographs of favorite horses of his past.

A News-Sentinel writer remarked, “Mr. Brown loved horses and never became entirely reconciled to the change.”

Expounding on remarks he’d made before, confirmed his prejudices: “The horse is the noblest of animals. Treat them right and they appreciate it like a human being. They have personality, affection, and intelligence. I wouldn’t give my favorite horses for all the automobiles you can crowd in that garage.”

Pryor Brown Obituary Photograph (Knoxville News-Sentinel, 1936)

Like a lot of successful Knoxvillians of his era, about the same time he built the House of Brown, he moved his residence to Kingston Pike, settling at No. 2387, not far west of Second Creek. There he died in 1936, of an unnamed chronic ailment. He was a locally famous man, both the combative Journal and News-Sentinel wrote separate editorial tribute to him.

The Journal remarked on his deft transformations. “It is not given to all men to pass with interest and success from one age and fashion of business into another that is new and different and to make a success, nor to many to become identified with the best practices and ideals of both. Neither is it given to every man to become himself so intimate a part of a city’s traditions that not even death can threaten the memory of him. Yet such was the life and record of Pryor Brown, a self-made man….”

“Nobody in Knoxville knows more people, or was known and liked by more than this veteran of life’s full weight of years. He will be missed from the well-known chair in which he has long sat as head of his business where he has been sought out by his friends from far and wide.

“A life like this becomes part and parcel of a city’s history and atmosphere, of its well-being and its growth, while the memory of the man himself passes into a tradition that Knoxville nor her people will soon forget.”

His son Charlie ran the company for several years after that. When he retired and moved to Florida in the 1950s, he wasn’t sure he trusted us to take care of his father’s old “gold bricks.” He had a mason pry them out and patch over the holes with conventional yellow bricks. They matched almost, but if you look at it when the light’s right, you can tell where they were.

It’s remarkable that Pryor Brown’s building was used as a parking garage into the 21st century, every day up into the Obama administration, and for most of that period, little businesses used the storefront offices, too. A cobbler, a travel agent, a beauty parlor, a realtor, an optician, and a copy center used the offices where Pryor Brown once hung framed pictures of horses, hoping you’ll ask about them.

By Jack Neely, January 25, 2023

(Knoxville News-Sentinel, January 19, 1936)

(Knoxville News-Sentinel, October 25, 1936)

(Knoxville News-Sentinel, October 14, 1937)

Leave a reply