Wonderful Flowers, Phantom Princesses, Painted Legs, Ghostly Hands, and the Ku Klux Klan

This has become a tradition, or a habit, which may be the same thing. Since the early days of Metro Pulse, I’ve written a column each about a Knoxville Christmas one century before. By my count, this is my 30th. So you could say we’ve been doing this every year since 1893.

It’s never been boring. Knoxville’s often torturous experience adapting to this imported holiday is different and surprising every year.

Now it’s time to picture Knoxville in 1922. One thing you’ll notice, if you have the opportunity to read over all our yuletide retrospectives, is that the city changed more, for better and worse, between 1893 and 1922 than it did between 1993 and 2022. We have cell phones now, which most of us didn’t in 1993. But do our recent advances begin to compare to the introduction of automobiles, airplanes, movies, radio? Not to mention architectural modernism, impressionism, cubism, communism, women’s suffrage, prohibition, phonograph records, football, jazz, and all the other things people first encountered in the late 19th century and early 20th. In my survey of 30 Knoxville Christmases, I’ve seen all those things introduced with newspaper headlines.

In the 1920s, America looked very different: buildings, the fashions, the means of transportation. It’s much easier to tell a photograph taken in 1893 from one taken in 1922 than it is to distinguish a photograph taken in 1993 from one taken yesterday. Sure, some things are different from a generation ago. But back then, in 1922, everything was different, and everything was new.

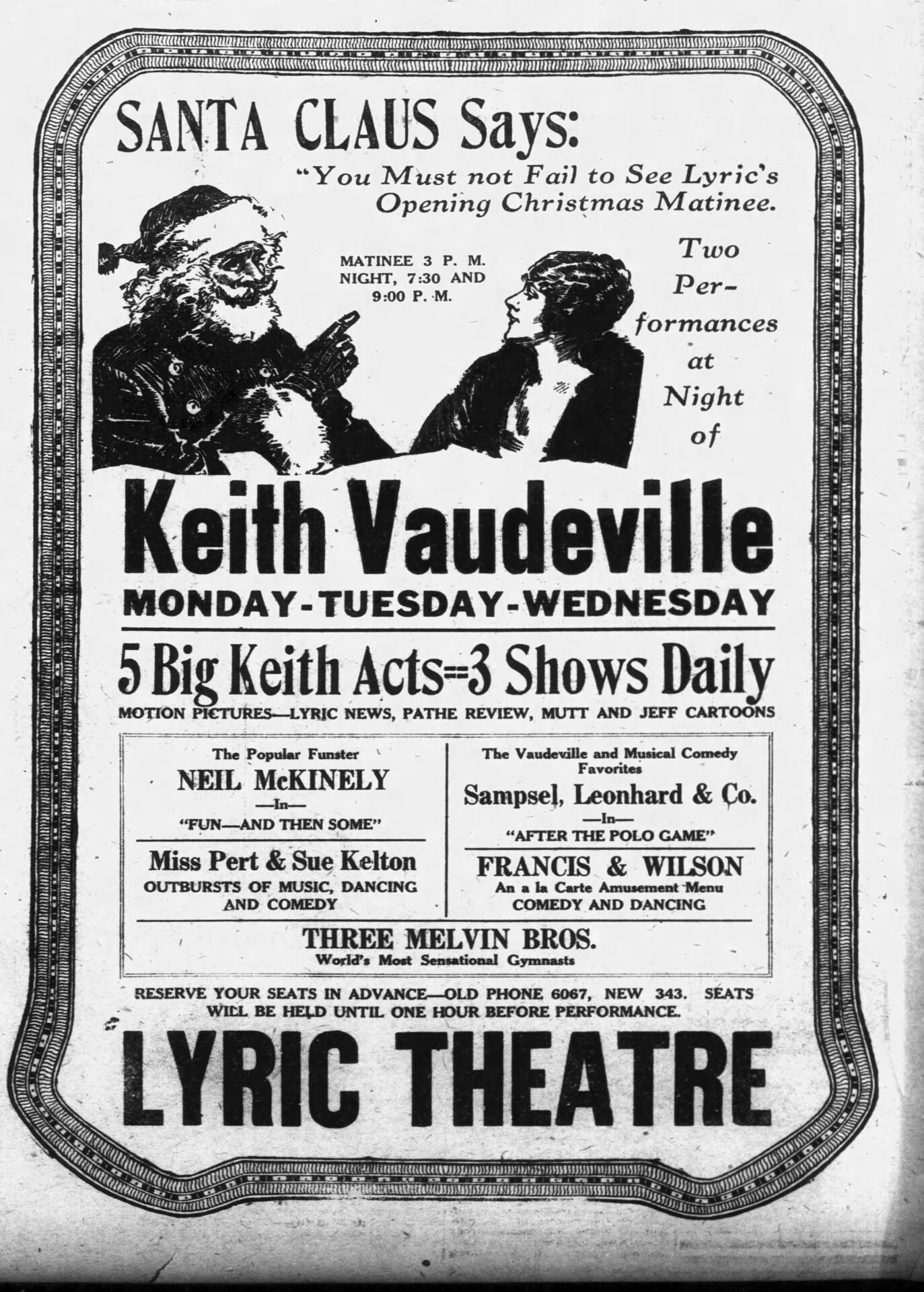

(Knoxville Journal & Tribune, December 22, 1922.)

And Christmas in 1922 was very different from the noisy, chaotic, often dangerous melee known as Christmas in 1893.

Knoxville in 1922 was a mostly industrial city of about 85,000, rapidly suburbanizing, as many affluent people had automobiles, and were eyeing recently rural spots as places to build houses.

The university, expanding rapidly during the administration of Canadian scholar Harcourt Morgan, was bigger than ever before, with over 1,000 students. The Vols weren’t yet national contenders. They’d had a winning season, losing only two, but some of the wins were against regional teams like Maryville, Sewanee, Carson-Newman. The bleachers on the west side of Shields-Watkins Field could hold maybe 3,200 fans, if they were skinny, as most people were. Among the Vols’ stars was Robert “Tarzan” Holt and a lanky kid from Madisonville named Estes Kefauver—who 30 years later would be a presidential contender.

***

In late 1922, details of Howard Carter’s discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun were trickling in, to have unexpected influences on Knoxville jewelry and architecture—just as Knoxville’s Republican politicos were abuzz about the prospect that one of their own—Judge E.T. Sanford—might soon join the U.S. Supreme Court. Some Knoxvillians with offices in the Holston Building had been on the phone with President Harding about that prospect.

For years, Sanford’s office had been in the Custom House, which also accommodated the region’s main post office on the ground and basement floors. By 1922 it was becoming painfully obvious that the 50-year-old marble building was not nearly big enough for a much-larger city in a modern era.

In retrospect, the biggest thing about December, 1922, was that it was the month Knoxville went on the air. Radio arrived in East Tennessee. But at the time, I’m not sure people knew what to make of that magical novelty.

A few people, especially teenagers, had already been building crystal sets to communicate with each other, but in December, 1922, the daily Knoxville Journal & Tribune, the newspaper run by 83-year-old Union veteran William Rule, went on the air in collaboration with the People’s Telephone & Telegraph. To hear it, you’d need a “receiving set,” a little wooden box with metal dials and earphones on a cord. The Journal’s announcements made it clear that anyone could listen, but if you tuned in, they wanted to know your name and address. In 1922, they were keeping a list of everyone in town who had a radio. They estimated there were at least 1,000 receiving sets in Knox County, maybe as many as 2,000. In a county of well over 100,000, the total radio market may have been about one percent of the population. Most of them were young, but one of them was R.H. Edington, an octogenarian who listened from his home on Bearden Hill.

That new radio station was called WNAV. It promised to broadcast lectures, sermons, and “musical numbers by Knoxville artists.” The first successful “test program” was on Dec. 14. Its content is obscure. But a Dec. 16 broadcast featured live performances from the 30-piece Amra Grotto Band; the Rusty Cannon Male Quartet; the Virginia Five, originally of Roanoke; local baritone J.L. Savard; guitarist J.C. Kimball; and mandolinist S.P. Graves. Also on the program was postmaster W.P. Chandler—a former cop from the saloon era—offering advice about mailing Christmas gifts on time, with an astounding offer. “Did you know that you can send by parcel post a dressed turkey or a dressed chicken? We guarantee to deliver all perishable parcels within an hour of receipt.”

(Chandler was, by the way, the father of Gordon Chandler, a war veteran known as a downtown gambler, who was at the time married to a shy young woman named Eugenia Williams. Many years later, after their divorce, she built a notable mansion for herself on Lyons View. But in 1922, she and Gordon seemed a happy, affluent young couple, traveling a lot together and living in a stylish apartment downtown.)

All performed live at the Deaderick Building, on Market Street, south of the Custom House. The program, probably the only broadcast of the day, went on for more than an hour.

Over the next few weeks, WNAV’s programming would expand but remain local, with lectures from familiar local politicians, editors and professors giving speeches and singers performing classical favorites and occasional folk tunes.

Knoxville’s first-ever Christmas broadcast, on Dec. 21, featured an address from UT’s Canadian-born president, Harcourt Morgan, and local singers performing the ancient carol “Lo How a Rose Ere Blooming” and works by Handel and Gounod.

Before the Christmas season was over, Capt. Rule, the octogenarian editor who had fought in the Civil War and was old enough to remember East Tennessee’s first railroad and telegraph, gave an address over the airwaves.

But it would appear nobody made a very big deal of it. Radio was still a hobbyist’s novelty.

***

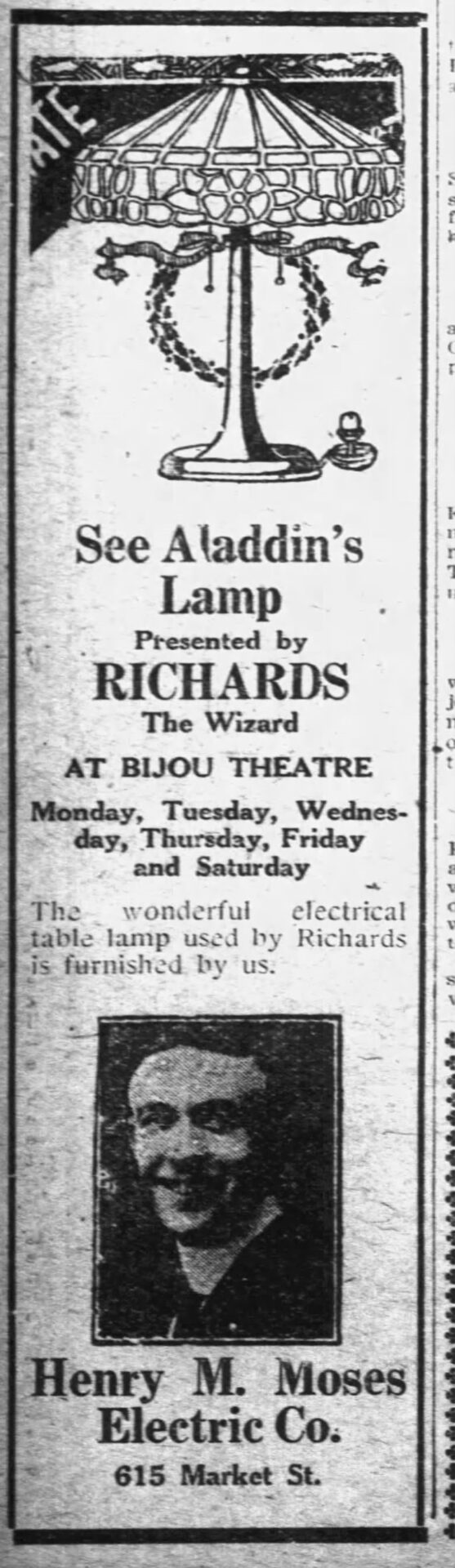

Perhaps more exciting at the time, or at least more promoted, was a fortunetelling magician at the Bijou, Richards the Wizard.

Are you afraid of spooks? Do you revel in the weird and uncanny?

Strange things appear, disappear, and reappear in the most amazing manner imaginable.

Wonderful flowers and phantom princesses spring up from nowhere.

Those cryptic lines appear in one of several advertisements. In 1922, the Wizard, whose cheerful face appeared in the newspaper several times, seemed to watch over the festivities almost like Oz. He beseeched Knoxvillians to submit questions for him to answer, including very personal questions about whether your spouse is fooling around. By Christmas Day, the Journal & Tribune was receiving dozens of questions for Richards per hour, more than they expected. They finally admitted that thousands would have to go unanswered.

As was the case every year, Knoxville was a regional shopping center, with a dozen sizeable department stores, including Miller’s, Arnstein’s, George’s, and Sterchi’s, plus more than 100 smaller specialty shops and the Market Hall itself, with its dozens of vendors. Thousands of shoppers arrived daily by train from as far away as North Carolina and Kentucky, many of them getting hotel rooms to accommodate their shopping adventures. Downtown hosted about 20 hotels, of various sizes, but the fanciest, largest, and most modern was the Farragut. Even if you weren’t staying there, you could dine there. Almost all retail was downtown, within walking distance of the two train stations.

Woods and Taylor (whose welcoming tile entrance would remain visible on Wall Avenue a century later) called itself “Outfitters for the Family,” but advertised mostly women’s garments. The popular gifts that year included “Philippine gowns” and kimonos.

Kids asked the various Santas for bicycles and velocipedes; electric flashlights; Kiddie Kars; “cats that cry meow,” mechanical toys, and, at S.H. George’s, something called “joy balls.”

Victrola and Edison phonographs were available at Sterchi’s, and had never been less expensive, or more popular, as not just classical music, but new jazz and blues records were available.

Hawaiian music was the rage, and ukuleles were new and fun and pretty cheap, at $1.50 each.

Knoxville Journal & Tribune, December 17, 1922)

The rich considered automobiles as gifts. The REO Speed Wagon, a prototype of the pickup truck, was especially popular; a local taxi company advertised that it was trying a new REO model. The Knoxville Motor Co. specialized in Nashes that year, both the four and six-cylinder models.

Richards the Wizard was touting Dodge as “a wonder car” which he claimed he had driven across the deserts of Asia and Africa in his search for obscure insights into the meaning of life. Mahan-Kerr Motor Co., the Dodge dealer, quoted him with his photograph.

The omnipresent Wizard did a lot of local cross-promoting that Christmas, appearing in ads for several local businesses. Roddy Manufacturing’s ad noted that Richards liked to drink Coca-Cola, and was known to give away dozens of bottles of it at his mystical events. He also liked Samuel’s Bread and Morton’s Coffee.

Doll’s Bookstore at 707 S. Gay Street was promoting interesting new books, including Sinclair Lewis’s startling satire of the thoughtless American middle class, Babbitt, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tales of the Jazz Age, a short-story collection which included “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.”

Almost everything was downtown, but those businesses north of the train tracks banded together to advertise: You can buy it in North Knoxville ACROSS THE VIADUCT where the rents are low and the quality is high. The viaduct, of course, was the relatively new Gay Street viaduct, an expensive wonder completed three years earlier. A Broadway viaduct was in the works.

Several of the new car dealerships were there on the north side.

Under the watchful gaze of the Wizard, Knoxville in 1922 seems all so silly and fun and modern that it’s startling to run across a reference to the Ku Klux Klan.

On Dec. 17, a week before Christmas Eve, the Ku Klux Klan made an appearance at the Market Hall. “We have been misrepresented, and we want to explain exactly what the Klan stands for,” they stated. The 1920s Klan was a national organization, and claimed to be mainly “patriotic” in nature. They advocated for free textbooks, fair elections, separation of church and state, and elimination of “party partisanship and corruption.” Openly, the Klan was opposing prostitution and bootlegging.

“Ku Klux Klanism is just a different way of saying 100 percent Americanism,” they claimed, mentioning little about race except to claim “The Ku Klux Klan is the best friend the Negro ever had—we don’t believe in social equality and neither do they.” Spokesman A.A. Barker claimed that he had freed a Black youth jailed for carrying a gun. He believed in the right to carry a gun.

“We are glad they were set free and we want them educated, but we want them in their place,” he said.

He was more concerned about the Catholics and Jews, who in 1922 were the Klan’s targeted enemy.

“The Roman Catholic and Jewish elements have held the balance of power politically,” said Barker, criticizing the fact that a member of Knoxville’s School Board was a member of the Catholic fraternity Knights of Columbus as “an insult to the protestants of Knoxville.” He was probably referring to John F. Shea, businessman, civic leader, and father of a Catholic priest who had been a popular member of the school board for a decade.

A second meeting on New Year’s Eve promised to highlight “the difference between Protestantism and Catholicism.” The Klan of the 1920s is often perceived as more concerned about foreign influence. No longer a regional organization, the new Klan was involved in controversies in New York City, and blamed for Catholic church fires in Quebec and Toronto.

Their meetings drew big crowds. But Knoxville institutions remained skeptical of the Klan, the Journal slyly noting that the organization’s secrecy suggested an attempt at wielding public power without accountability. Captain Rule’s Journal, which often ran long pieces about visiting lecturers, often transcribing their entire speeches for the newspaper, offered only a short page-14 story about it.

Before the end of the decade, Barker and the Knoxville Klan would fade from the headlines. But there was no questioning that race was an issue in Knoxville, and whether things got better or worse in the ‘20s is complicated. The 1920s saw the rise of jazz and the introduction of African American performers to mainstream stages, as the blackface minstrel era faded. But some new theaters were opening as whites-only establishments. That was unknown in the Victorian era, when even the fanciest theaters tended to admit both races in segregated circumstances. The ’20s also saw the standardization of racial “covenants” that assured white home buyers in new residential developments that they would never have African American neighbors.

Knoxville’s Black population actually increased by over 50 percent in the 1920s, creating a lively alternative culture of pool halls and dance halls centered along East Vine Street. It’s where the Delaney family lived, and where charismatic young Beauford, who turned 21 just after Christmas, was working on his early paintings. And it’s where even younger Carl Martin and Howard Armstrong, musicians in their early teens, were beginning to perform for nickels on the streets.

The holidays always see creative giving opportunities, and by one account, 12,000 baskets of food had been given out to Knoxville’s needy that season. But that year, there was something new in the works. That December, a few community leaders were establishing the city’s first chapter of something new called Community Chest—the forerunner of what would later be known as United Way.

***

Christmas Eve was always the height of the chaos. At the old post office, a reporter remarked, “The halls of the post office had the appearance of a gridiron on which two football teams battled desperately.

With hats awry women laden with packages scrambled madly. Long lines of chafing humanity stooped and swung one way and another…. Rushing and pushing, the ever-changing crowd seemed to realize the spirit of the day, for smiles appeared on many faces, and few harsh words were heard.”

At Whittle Springs, starting Dec. 19 and going through the holidays, the Royal Wabash Orchestra, a seven-piece dance band based in New York and advertised as “the most popular dance orchestra in the New England states,” is playing three nights a week, including Christmas Day, until Jan. 6, the traditional end of the holiday season.

Despite their worldly reputation, a scan of national sources for bands of that name suggests that Christmas season at Whittle Springs was the all-time high point of Royal Wabash’s career. If they were indeed “famous,” as advertised, it’s not obvious they ever played anywhere else.

On Monday, Dec. 25, several downtown restaurants and hotels offered special Christmas dinners. Foster’s Sweet Shop at Gay and Church presented a turkey dinner with oyster cocktail, cranberry sauce, creamed potatoes, olives, biscuits, and English plum pudding.

The Gold Sun Café, the Greek-owned place at the northwest corner of Market Square, served something similar, turkey dinner, but with more options, leg of pork or loin of beef, or roast chicken with oyster dressing, with asparagus on toast, chilled hearts of celery, Waldorf salad or a wedge of lettuce with Thousand Island dressing, a former regional New York specialty that was just becoming nationally popular.

Stores were mostly closed on Christmas—gone were the days early in the century when stores would stay open on the morning of the 25th for late-late shoppers. Even the Market House was closed. But movie and vaudeville theaters were open. For them, it was a very big day.

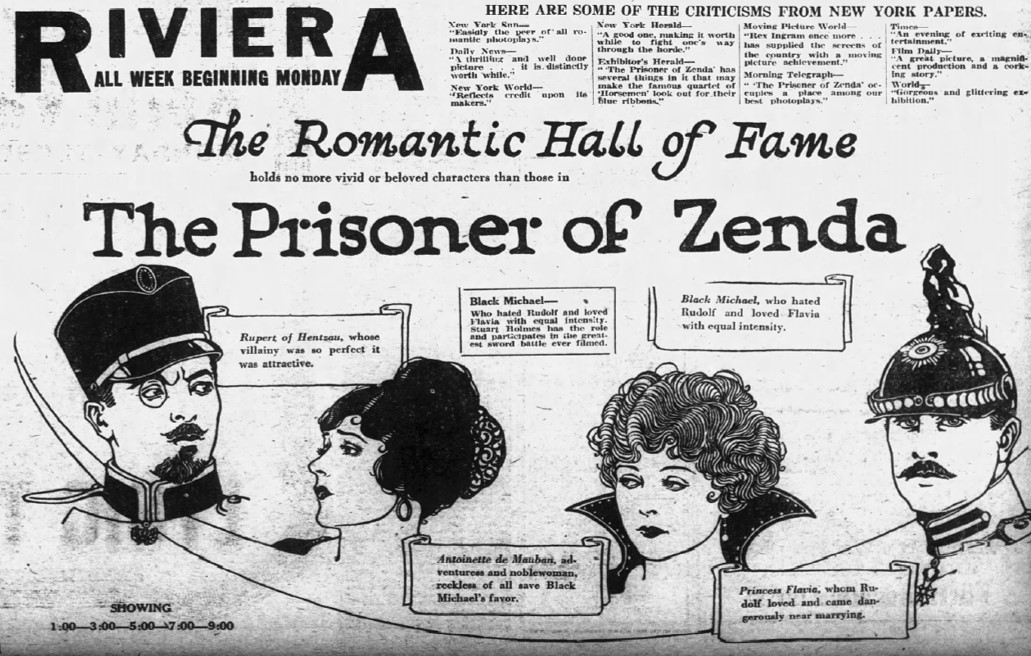

The newest theater in town was the 1,000-seat Riviera. There the new two-hour version of The Prisoner of Zenda, featuring the young Ramon Novarro, ran for the entire Christmas week, an unusual duration for a movie in those days.

(Knoxville Journal & Tribune, Dec. 24. 1922.)

The Queen Theatre, across the street from the Riviera, was showing 23-year-old sex symbol Gloria Swanson’s controversial Her Gilded Cage, which featured her “painted legs” and “negligee scenes in a boudoir episode.” Unfortunately, no copies of that Paramount film exist today, and we know it only from brief descriptions from 1922. (The Queen would close six years later, as the Tennessee opened.)

The Christmas movie at the Strand, on Gay near Wall, is a similar story. The Outcast, a melodrama featuring lively beauty Elsie Ferguson as well as the young William Powell, in a small role. Sometime in the years since that Christmas, 1922, we lost track of that one, too.

(Knoxville Journal & Tribune, December 24, 1922.)

The Lyric, Knoxville’s largest and oldest theater—it was previously known as Staub’s—was trying out a national vaudeville network, the famous Boston-based B.F. Keith circuit. Among its dozen entertainers in that first Knoxville run, opening on Christmas Day, were gymnasts the Melvin Brothers, a short musical comedy called “After the Polo Game,” “the popular funster Neil McKinney”—and Pert and Sue Kelton, who were “an outburst of music… Their act, it will be remembered, is jazz—all jazz—strictly jazz.”

Jazz was still a pretty new concept to mainstream America, and its popularity was spreading more via vaudeville than through concerts, records, or radio.

Pert Kelton, only 15 when she performed in Knoxville that week, would later become a familiar comic character actress on Broadway and in Hollywood, including, 40 years later, a turn as Mrs. Paroo in the movie, The Music Man.

By the way, in 1922, some Americans never got to see a woman conduct an orchestra. But in Knoxville, was Bertha Walburn was putting together the prototype for the Knoxville Symphony, another conductor, violinist Margaret Conner, was the leader of the Lyric house orchestra.

You could do any of those things on Christmas Day, 1922. Or try to do two or three.

Directly across the street at the Bijou, magician Ralph Richards—billed as Richards the Wizard—was opening his weeklong run.

That Christmas Day, Richards “puzzled and pleased two audiences,” demonstrating “modern feats of mysticism bordering on the spiritualism and the supernatural,” went the Journal & Tribune’s review.

One of the features that made it seem “modern” was that Richards featured a Victrola, playing music on stage, which vanished before the eyes of the audience. (Sterchi Bros. Furniture wanted to be sure that everyone knew that you could buy a Victrola just like it down the street at their big store.)

“One does feel peculiar when a hypnotized woman floats through space…. By some means or other, far be it from us to vouchsafe a guess as to its operation, figures of the dead, ghostly hands, and other inhabitants of the world beyond, cavort before the audience.”

***

About a month after Christmas, A.A. Barker, Knoxville’s most outspoken Klansman, announced that he had commenced impeachment proceedings against the city attorney general, R.A. Mynatt. Over the next few months, he repeatedly declined to discuss his grounds with the press. A colorful and popular figure at the courthouse, Mynatt was unworried about the action, and retained his post for several years, after which he became a city judge. Barker would drop out of public view before the end of the new year.

Richards the Wizard apparently never returned to Knoxville, but toured his amazing act across the South, the Midwest, and parts of Canada over the next 10 years or so, but then began working in radio. About 19 years after his Christmas Bijou show, one Ralph Richards, a.k.a. Ennes, as a result of his radio work, was in trouble for mail fraud. He was convicted twice and incarcerated at Leavenworth, and is considered one of the cases that prompted the Radio Control Act, resulting in the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

Which the musicians and lecturers at the microphone at WNAV didn’t have to worry about.

So Merry Christmas. You just never know.

Jack Neely

Leave a reply