Our first big street fairs set a high bar for Fun, but also presented an early flowering of African American culture

Imagine October in Knoxville, and subtract Volmania, drives in the Smokies, and Halloween decorations, and what would you have? In the late 19th century, football was just an eccentric club sport; there were no paved roads in the mountains and no cars to drive on them; and Halloween, to the few who were familiar with it, was just a bit of fortunetelling drollery hosted by just a few affluent families on a single evening.

But on certain Octobers between 1889 and 1913, we had more creative and unpredictable fun than we ever have today. During that era, October was mainly the season of the annual Carnival.

It was the era when Knoxville made its debut as a real City, and the Carnival seemed the ultimate proof of the old town’s arrival. Knoxville had electricity and a telephone system; a new public library; dozens of new factories, making furniture, textile, machinery, marble products, train cars; architectural firms busy with new buildings; a railroad station with trains arriving at all hours of the day and night; public transportation, by muledrawn trolleys soon to convert to electricity; a semi-pro baseball team that won regional championships; and soon enough, it had a street festival.

It was a spectacle like nothing before or since, and seemed to involve everybody of every race and national origin in one way or another.

By some accounts the Carnival began in 1884, understated as something more modest-sounding than it was: a “Trades Display.” That term hardly suggests 1,000 working men and countless horses pulling wagons in a parade that lasted 48 minutes. It was also at least occasionally known as the Great Feast of Industry and Enterprise. It appears to have been inspired by similar events in Baltimore and Philadelphia; the latter city was having a hard time stopping the celebration after its successful World’s Fair in 1876, which hundreds of Knoxvillians attended.

It got only bigger after that.

The following spring brought open regret that the city and its leaders weren’t ready to mount the same festival again in May. As it happened, they were indeed able to do so by late September. That delay in 1885 may be the reason it was known in years to come as a fall festival.

By then it had evolved into a four-day event involving a parade representing 65 local industries, including those who made boxes, buttons, fences, buggies, cigars, pipes, bottles, soap, trunks, and dozens of other items manufactured in Knoxville at the time, with 50 horsedrawn floats, one of which featured a local importer flinging free packages of Brazilian coffee to the crowd; in the river, a regatta of rowing teams, organized by the Cherokee Boat Club; multiple horse races at the riverside park of the Tennessee Turf & Fair Association (at what’s now Suttree Landing); and, at that venue, the “Tournament,” involving dozens of local “knights” in medieval plumage competing in faux-jousting contests, usually involving spearing rings with a lance. The festival ended with a “Coronation” at Staub’s Opera House on the final Friday night.

Emma Abbott, the world-renowned opera singer, then aged 34 and at the height of her fame as “the People’s Prima Donna” and the first female chief of an American opera company, coordinated her Knoxville performances with the Trades Display, producing four operas in a row, mostly light Italian operas sung in English, plus Gounod’s Faust, all at Staub’s Opera House. With her company were several singers with reputations of their own, including Venezuelan tenor Fernando Michelena.

The Hockenjos cigar company entered a float featuring a 10-foot cigar; German-speaking immigrants Metler & Ziegler featured a float-sized meat rack. Quarry magnate John J. Craig’s float was 16 mules pulling 12 ½ tons of marble, just to show what they could do. Real estate was booming at the time, so realtor J.B. Cox rode through sitting atop a valuable load of dirt. Spiro & Brother, candy and cider manufacturers from Hungary, gave away free cider along the parade route. Massachusetts-born Perez Dickinson’s float boasted of his experimental farm at his Island Home, in which his represented “South America”—the joking term for remote South Knoxville—with a couple of country fiddlers, Bart Giffin and Dave DeArmond, both of whose names appear in histories of the early popularization of country music, as half of Gov. Bob Taylor’s quartet known as the Market House Fiddlers.

It was a more imaginative parade than any in our modern era. There were an elephant and two lions, perhaps just sculptures of them, descriptions are vague—but also live bears in a cage, with the added thrill of including a little boy in the cage with them.

Black people had at least some part in every Carnival. The Slater Mechanical School entered a float in the big parade, bearing a full load of its pride, the African American students who attended. The 1885 fair’s big parade also included Richard “Uncle Dick” Payne, then aged 76, and his “Water Works.” Then, just before Knoxville had a municipal water works, Payne provided fresh water from a spring, by way of his mule-drawn barrel, to Knoxvillians of both races who lacked a well or other private source of water.

It sounds as if the street-festival idea had some hiccups after that, announced but not held, then delayed, as if the city was intimidated by ever again doing anything on the scale of ’85. There were some street fairs, but perhaps nothing quite as extravagant as a Regatta, and a Tournament, and an Opera Festival, and a big no-holds-barred Parade, and a Coronation and associated Ball, all in the same week.

However, in 1889, largely in celebration of the new train to Cumberland Gap, the K.C.G. & L, they tried the Grand Carnival in October. For the first time, parts of it, including the Tournament and a grand military parade, made up of both veterans and young cadets, would take place at Elmwood Park, later known as Chilhowee. But it was a citywide thing, and most of the fun was downtown, where a parade featured more than 100 firms, several with multiple wagons, parading under new electric lights that “made Gay Street nearly as light as day.” The booming Haynes-Henson Shoe Co. paraded with a float representing the old woman who lived in the shoe. Raf Marmora, the Italian-immigrant fruit vendor, had a float. Knoxville Brewery was there with its beer wagon.

F.E. McArthur, which sold pianos and other musical instruments, awed crowds with a lush tropical scene. An October Carnival was no time for logic. Wholesale Dry Goods store Cowan, McClung & Co., perhaps the largest and most practical store in town, featured “an Elephant drawn by eight horses and as many Turks in costume.”

In addition to businesses, there were fire engines, “Bicyclists in costume,” the Chilhowee Boat Club with an impressive nautical float; “Riders in gay tournament costumes,” “two mounted field guns from the university,” and several bands, including Crouch’s orchestra and the Newman Juvenile Band. It was sufficiently impressive.

“Brass Bands Blowing the Blasts of a Business Boom,” wrote a alliterative-minded headline writer for the Sentinel. “Merchants and Manufacturers Meet and Marvel. Bolts of Bright-hued Bunting Beam from Beautiful Buildings.”

The parade offered no obvious limitations to any entity who could afford to assemble a float. One proud hunter created a float “bearing a persimmon tree loaded with live possums clinging with prehensile tails to its swinging branches.” He sat happily beneath, with his rifle in his lap, surrounded by hunting dogs.

One overwhelmed newspaper reporter gave up. “The Sentinel cannot pretend to give an approximate idea of the grandeur or the immensity of the affair, as such things must be seen to be appreciated.”

A Chinese immigrant known to us as Wall Lee ran a linen shop on Gay Street in 1889. He showed his exhilaration during the parade by flying a Chinese streamer alongside a U.S. flag.

According to news reports, thousands crossed state lines to witness it. Trains were loaded, the aisle crowded. A visitor from Indianapolis claimed it was the best. “I’m completely amazed,” he said. “I had no idea Knoxville had such possibilities in her.”

The following years brought distractions. A couple of massive Civil War veterans’ festivals, the Blue-Gray Reunions, were mostly military in nature, but very popular, with thousands in the streets. And there was also the economic depression of 1893-94, which nearly ruined Knoxville, and set back the city’s dreams of being an impressively festive place.

Some conservatives proposed that it would be easier, safer, and thriftier to hold just a big version of a county fair. But every county in East Tennessee had one of those, said lawyer R.W. Austin, a Republican politician, a future congressman and diplomat. He declared that “it was the duty of Knoxville and Knox County to surpass this county-fair idea, and present something on a grander scale.”

In the mid-1890s, Knoxville’s big crazy street festival came roaring back.

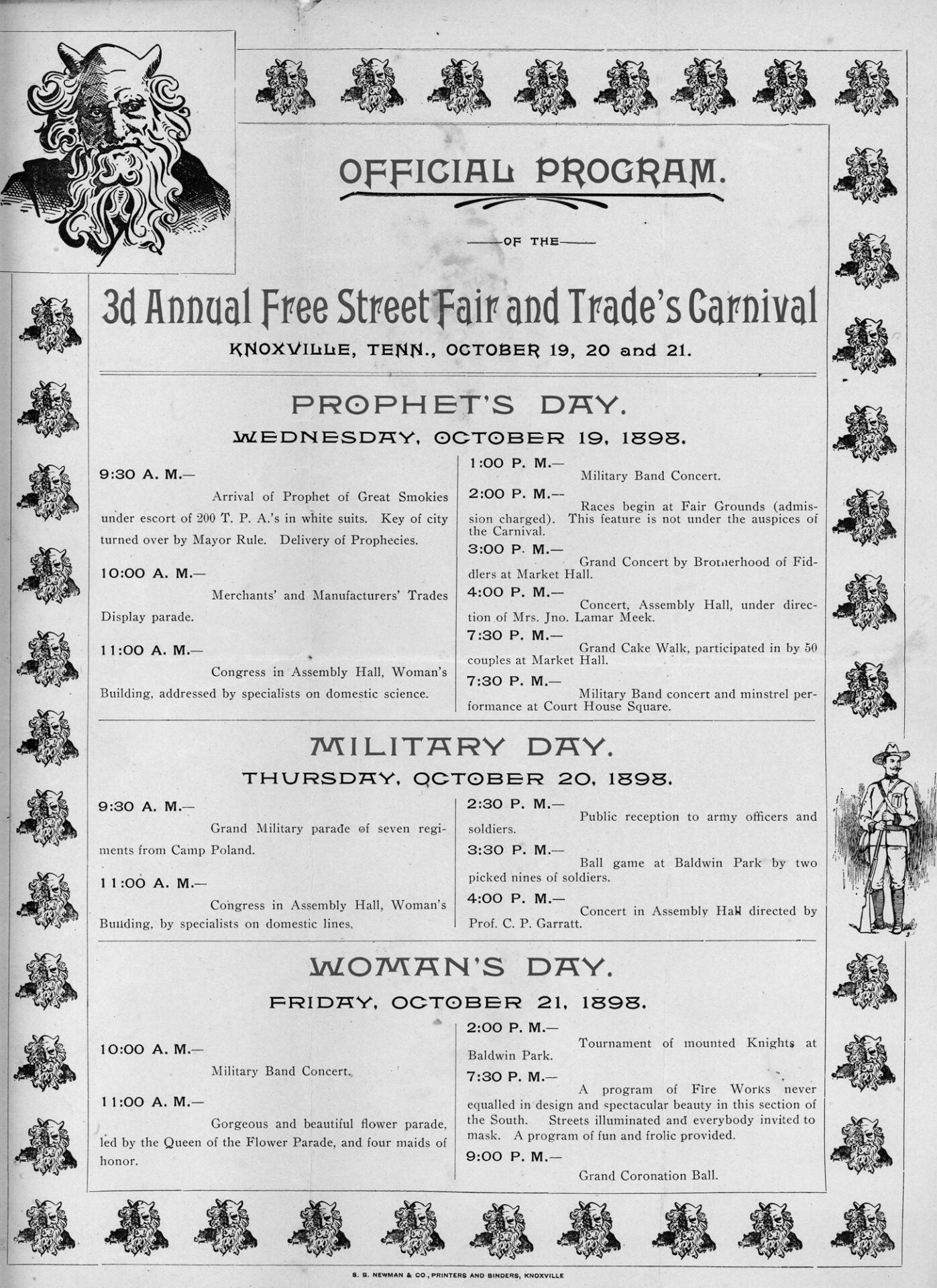

No longer a mere “Trades Display,” it was now the Carnival. Or, more formally, the “Merchants and Manufacturers Free Street Fair and Trade Carnival.” During the generation of the fin de siecle, it became October tradition.

Knoxville was growing so fast that many residents were newcomers who didn’t even remember the big events of the decade before, so it seemed like a whole new thing.

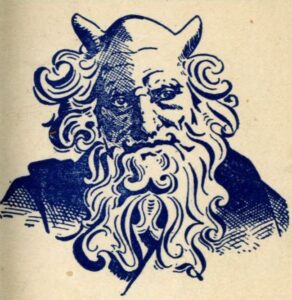

It launched on Oct. 21, 1896. A new feature was the arrival of “the Veiled Prophet of the Great Smoky Mountains.” The Prophet appeared, as ordained in the press, on the Gay Street Bridge, an old man with a staff, a long white beard, and twin horns on his head.

It was an elaborate costume, of course, a disguise for a prominent citizen whose identity remained unknown to the public, though some may have guessed. Greeting him at the Sevier monument on the courthouse lawn was Mayor Sam Heiskell, after which the Prophet would speak, and make an extravagantly optimistic prediction for the future of Knoxville.

He rose and with great solemnity seemed to predict a Republican victory for presidential candidate William McKinley, who had visited Knoxville earlier that year. “The growth of this city is unparalleled in the history of cities,” he intoned, “and I prophesy that within a few years it will have a population of 500,000.”

He proceeded with lots of attendants down Gay Street, to be greeted from the balcony of the Hotel Imperial—at the location of the current Hyatt—by distinguished visitors. Although his identity was never reported during the Carnival, that first Prophet was later alleged to be the well-known artist Lloyd Branson, then in his early 40s, who the same week presented a rather complicated city flag of his own design to Mayor Heiskell.

In years to come, other prominent citizens would don the beard and horns to make their solemn and always optimistic pronouncements about Knoxville’s future, among them a Civil War hero, Union veteran Gen. John T. Wilder, and Col. L.D. Tyson, then best known for his service to the Cavalry in battles with the Apaches. (Several years later, he’d be a brigadier general leading troops against the Germans.)

The idea for the Prophet of the Great Smokies was inspired by the mysterious figure of that name in a recent story by Middle Tennessee fiction writer Mary Noailles Murfree. Murfree herself formally attended the festival, speaking at the Women’s Building, a temporary pavilion on Gay Street, which hosted musical performances and female speakers, including future suffragists. On exhibit there were prize-winning foods and antiques, but art was one of its biggest draws, and it was one of the first exhibitions of the paintings of 17-year-old Catherine Wiley, not yet known as Tennessee’s greatest impressionist. Also a subject of discussion was a quilt on display, created by an elderly woman remembered only as “Mrs. Evans,” with an embroidered poem with a quotable stanza:

The time is fast coming

Please to take note

When the men will darn

And the women will vote.

That night at 8:00 the Carnival welcomed a “Grand Illuminated Bicycle Parade”—it sounds like an early precedent for what we now know as Tour de Lights—followed by a “Grand Musical Contest.”

There was a lot going on, so much that no one person could see it all. That first year featured a UT football game, played on a Thursday afternoon at 3:00 at Chilhowee Park, a game in which the opponent was first announced as University of Virginia. But UVA must have had something better to do that day, because UT’s opponent is recorded in athletic records as Kentucky’s Cumberland College. (That season of 1896 is remembered as the Vols’ first-ever winning season, when the helmetless lads, who sometimes wore orange but weren’t yet called “Vols,” won all four games.)

But in those days, football was still considered an odd Yankee novelty, and a passion for only a few. There was little reporting about it, and overlapping with that game were other sporting events miles across the city, both downtown and at Baldwin Park, north of Fort Sanders, where local baseball was a bigger attraction that football. There followed, that evening, the “grand and imposing, historical, allegorical, emblematic and spectacular illuminated carnival pageant.” That was the big downtown parade. They gave awards not just for the best floats, but for the “best illuminated building.” Electric lights were still new, and part of the spectacle.

Newspapers reported that 40,000 people lined Gay Street to witness it. (When was the last time we had a street crowd like that?)

On the third day was the “grand boat regatta,” a feature of several Carnivals. It was a rowing race that Friday morning, starting from the Cherokee Bridge—the bridge that connected Kingston Pike with the abortive Cherokee residential development on the south side of the river, the land acquired about 20 years later by UT. Entries, according to promotions, were “open to the world.”

Then a “grand musical band parade” downtown, followed that afternoon by “exciting sports on streets.”

That evening came the “Grand Fantastic Fantasma,” in which people living in the country were invited to ride horseback down Gay Street wearing “grotesque disguises.”

And, of course, there were speeches. Chattanooga politician James B. Frazier, who a few years later would be governor of Tennessee, spoke at the Harris Building, which would in future years be better known as the home of Regas Restaurant.

The finale, Friday night, was the Empire Ball, at which they crowned the carnival’s emperor and empress. It opened with an orchestra playing the march from Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust. That year, the theme was strictly Napoleonic, with a locally notable Napoleon impersonator, and an “Empress” announced as Josephine. A character representing the Pope of Rome was part of the show (the organizers knew their history; 92 years earlier, Pope Pius VII was the officiant of the coronation of Napoleon and Josephine). It was a fundraiser for Knoxville’s yet-to-be-built first public hospital.

Then, as always, came fireworks.

***

Of course, 1896 was also the year of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy vs. Ferguson “separate but equal” decision, which codified racial segregation in America for the next six decades. By degrees after 1896, the separation of the races became stricter than it had been for most of the 19th century.

In some cases, segregation concentrated African American culture. In 1897, the Carnival hosted a Negro Building. It wasn’t presented as one of the main features of the Carnival, but it was nonetheless described in some detail. (Earlier this year, KHP’s UT intern, Thomas Mahoney, turned up some details about it, and we went back and found some more.)

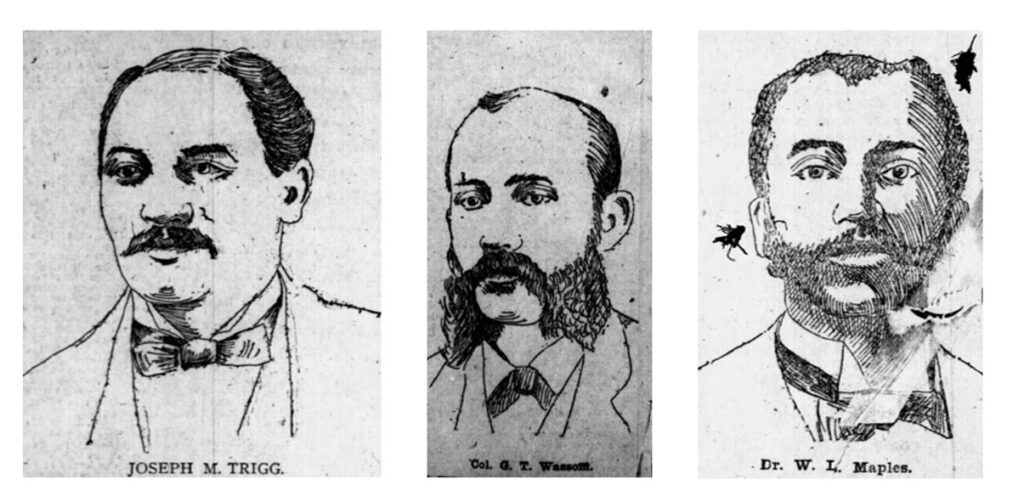

The main figure behind the Carnival’s first Negro Building was a young man of 30 named Joseph Trigg. Originally from Virginia, he was college-educated, and had worked for a time as a teacher. He came to Knoxville in 1889 and co-founded a Black newspaper, The Negro World, later renamed, optimistically, The New South. He was chosen to be bailiff of the U.S. District Court, an unusual honor for a Black man in the South. The following year, he would be elected, and later re-elected, to Knoxville’s City Council.

Trigg was one of the three main organizers of the first festive Negro Building. Joining him was George T. Wassom, an attorney who would be an outspoken activist for African American rights—and Dr. W.L. Maples, the well-known physician physician. The Negro Building was part of the ’97 October Carnival, and featured exhibits of African American achievement, including art exhibits, agricultural displays, and Civil War relics.

Knoxville leaders of the Negro Building, from left: Joseph Trigg, George T. Wassom, Dr. W.L. Maples (Knoxville Journal & Tribune, Oct. 10, 1897)

Cal Johnson, the already famous saloonkeeper and real-estate developer who had risen from slavery to business prominence, was one of the original organizers, but when he found he was too distracted by horse racing, another attraction of the Carnival, at Flanders Racetrack, along what’s now Western Avenue, another Black Knoxvillian, successful farmer and florist Ben Maynard, joined the original organizers.

The Journal & Tribune, Captain William Rule’s Republican paper generally liberal toward race relations, ran a headline:

COLORED PEOPLE TO HAVE A PART IN THE GREAT CARNIVAL THIS WEEK

It was reported that a “Mrs. Dr. McCreary” of the new city hospital made it seem like a good idea.

It was described as “across from the old Flanders Hotel,” with one source giving its location as 716 Gay Street, a building generally used by the Republican Party.

It was a challenge to mount, because there was already a “Negro display” at the Knoxville Building at the Centennial Exposition in Nashville. Much of the Black community’s best was 200 miles away.

Still, the Carnival exhibit at the Negro Building was a wonder to behold. Knoxville College had a special exhibit about its programs, as did the Slater Training School, an industrial vocational institution. It sounds as if they were practical and instructive.

There was a wide variety of handiwork, quilts, needlework, many articles of handmade clothing. “Uncle” Jimmy Henry tended his exhibit of rustic furniture in person; born into slavery, he was reputed to be about 104 years old.

Accompanying him was his new wife, Emily, who was not much younger than he.

On display were a few paintings by artists whose names are now obscure: Annie Prosser, S.C. Smith, and Rosa Weston.

Agricultural exhibits at the Negro Building, included rye, corn, wheat, and pumpkins, and live rabbits and chickens.

But in part, the African American exhibition was a museum of historical curios. There was a Japanese sugar bowl from 1825. And a kettle once used by Andrew Johnson in Greeneville. There was an antique piano reputedly made in London in 1782, contributed by Wesley Stuart, an elderly former Virginian born in slavery who had moved to Knoxville in the 1840s. He also brought a shovel used for a barbecue for William Henry Harrison’s famous presidential campaign in 1840. (Was it, for its few days, Knoxville’s first historical museum?)

Tending the valuable exhibit were two armed guards, one of them Houston Lust, a 30-year U.S. Army veteran who had served under Gen. Nelson Miles, the Union veteran who had led campaigns against the Comanches and the Nez Perce. There, Lust had known Buffalo Bill as a fellow soldier. He brought his own exhibits, mostly Native American artifacts, war relics and a peace pipe. Also, something you might not expect to be in the possession of an old Wild West cavalryman: a 1747 violin of unrecorded origin.

Black and white attendees both visited, and among the visitors to the Negro Building was newly re-elected Gov. Robert Love Taylor, who said he was “highly pleased” with the exhibit.

***

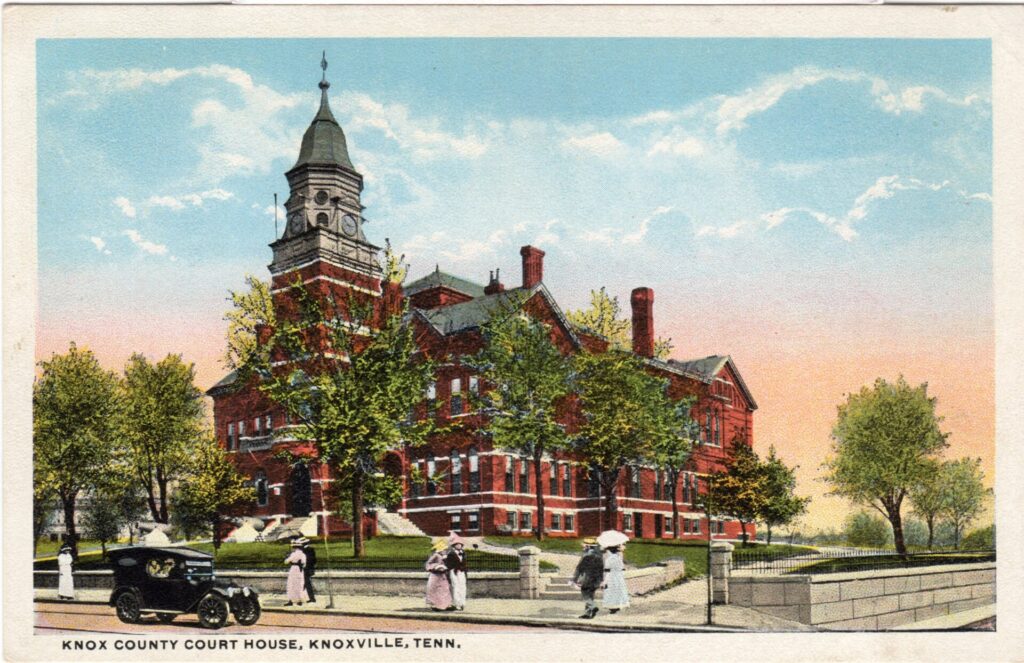

The Carnival made room for another Negro Building the following year, but perhaps because of the disruption of the Spanish American War, for which Knoxville served as a training base for thousands of troops from across the country, they had trouble securing a location. It was first announced the exhibit would be located at an unspecified spot on Vine Street, then Commerce Street near Gay. But it finally landed in the public hall of the courthouse itself.

Decorated with palm trees, some of them from as far away as South America, “the county courthouse will present the appearance of an earthly paradise,” said Wassom, “and in its booths will be placed the art and handwork of thousands of our people.”

Just inside the door was a poultry exhibit, featuring live ducks and chickens. Across the hall, exhibits of Knoxville College, the Slater School, and the Cosmopolitan Library and Industrial School.

The Knoxville Sentinel ran a story, “Negro Building is a Credit,” mentioning dozens of exhibits, and opining, “The culinary exhibit would make anyone hungry.” Another article in the rival Journal & Tribune, titled “Creditable in Extreme,” mentions that the exhibition included biscuits, custards, canned fruit, and raspberry and rhubarb wines.

There was art, including Anna Prosser’s oil painting of geese in a pasture (she was also a performing musician), and a calico quilt by 10-year-old Hattie Armstrong.

“The relics are numerous and interesting,” went one newspaper report. “They range in age from one to 200 years. Among them is the pinnacle made by Gov. John Sevier to ornament his smokehouse.”

A few were recycled from the previous year’s display, but several were novelties, including a candlestick from the late 1600s, a 1700s spinning wheel, and a cane made by imprisoned Union soldier in the notorious Confederate camp in Virginia known as Libby Prison.

Unnoticed by most observers at the time, but later awarded by a carnival committee, was a display of books by African American authors.

The brass band of the Third N.C. Regiment performed on the courthouse lawn, reportedly “all the time.” They hosted a special reception for Black U.S. Army officers attending the festival.

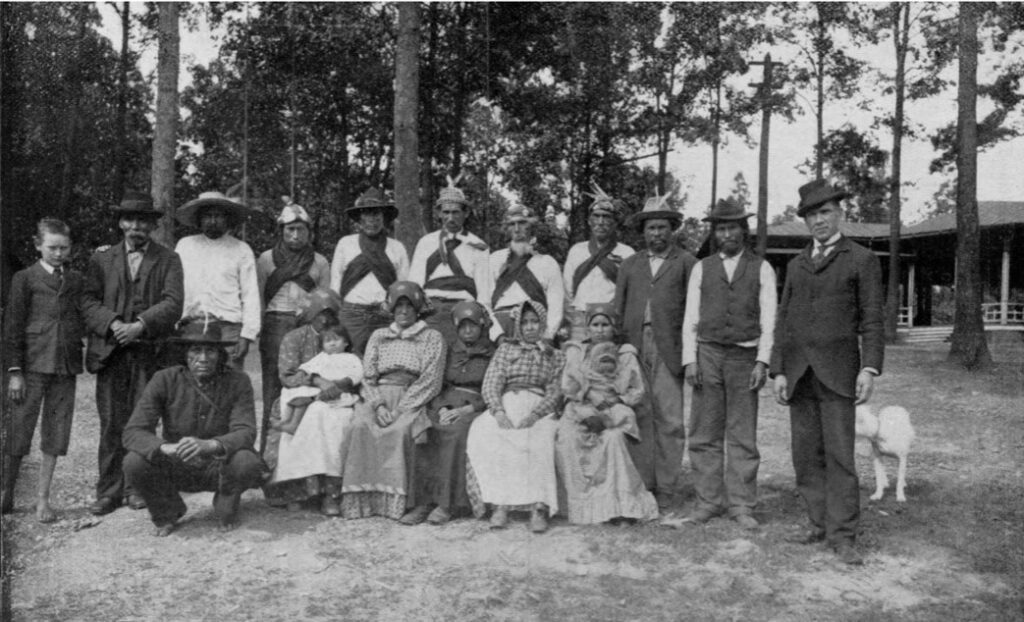

“Native Cherokees, from the Cherokee Reservation, North Carolina, as they on their visit to Knoxville during the Street Fair and Carnival, 1897.” (McClung Historical Collection)

The 1898 Carnival, again sanctioned by a visit from the Prophet, was a military but also a musical affair, featuring the Legion Band of Army buglers, and a review of the troops, many of them training for the Spanish American War, reviewed by Gov. A.S. Bushnell of Ohio, who’d made a special trip down for the event.

It also featured a Reunion and Concert of the Brotherhood of Fiddlers at Market Square. (Public fiddling had become a Knoxville tradition since an early Music Festival in 1883, and is considered by historians an early influence on the growing popularity of country music.)

Knoxville’s tastes were diverse. Mary Fleming Meek sang a soprano solo at the Market Hall. Thirty years later, she would write UT’s Alma Mater.

***

The 1899 Carnival okayed something of a wild card, a bizarre feature sponsored by the Elks Club. At the intersection of Gay and Jackson, they hosted something like a circus, but perhaps more bizarre, transforming their urban setting into “The Streets of India,” with elephant and camel riding, as well as rides on the “Sacred Donkeys.” Among the attractions were Si Hassan Ben Ali’s Arab Acrobats; Prince Ishmael, the Great Magician; La Belle Rosa, the Coo-Chee Dancer; Speedy the High Diver; and Roscoe, the Australian Snake Eater: Half Snake and Half Human. Their ad featured a perhaps urgent plea: “wanted: 500 snakes for Roscoe.” The Elks claimed “The largest number of Sword Fighters, Egyptian Dancers, and Curious People from Every Clime Ever Exhibited in America.” Unlike most of the Carnival’s free attractions, it cost a dime to enter; it was a fundraiser for the Elks’ charity works.

There was a complaint that the Carnival had not accommodated the African American exhibit with a larger space. It was too popular for its rooms at the courthouse. It was estimated that 10,000 visited the Negro Building in the Knox County Courthouse on its final day. All races were welcome, and for many Knoxvillians who were not of African ancestry, it was a rare opportunity to glimpse a side of a culture obscure in mainstream public life.

Despite the complaints, the show was held at the courthouse in 1899, and received unanimous praise.

Knoxville Postcard, circa 1905. (Alec Riedl Knoxville Postcard Collection)

In 1900, the courthouse was once again available, but no further support came from the city. The Negro Building’s Finance Committee, composed of A.S. Jones, Cal Johnson, and C.C. Dodson wrote an open letter pleading for money from the Black community to support the exhibit.

It did happen that year, for a fourth time, though it’s not as extravagantly described in the paper as it had been in years past.

A couple of phenomena may account for that. One was that mainstream society in Tennessee was getting stricter about segregation, often resulting in simply shutting African American participation out.

Dr. Maples, who had been a prime organizer of the original Negro Building, moved to the new U.S. territory called Hawaii that year, along with his brother, Sam, one of Knoxville’s first African American magistrates. They said they liked it there, and that wages were generally much higher than in Knoxville, and that African Americans actually had an advantage over Hawaiians in industry, many of whom didn’t speak English. Maples returned to try to recruit more African Americans from Knoxville to join him. More than 50 did so, most of them presumably Black families with means. They may have taken with them some of the spirit of the Nineties.

Early in 1901, Councilman Joe Trigg resigned to take a job with the U.S. Post Office in Washington. Though Trigg occasionally returned, he would spend most of the rest of his life and career in Washington.

Later in 1901, attorney George T. Wassom, another of the original three organizers of the Carnival’s Negro Building, announced he was moving to Kansas. Opportunities were better there, he reported.

So by 1902, the original Carnival-organizing trio of 1897 cadre had all left Tennessee. Their ally Benjamin Maynard, the farmer-florist from South Knoxville, remained. He and his wife, Phyllis, remained involved in Knoxville’s agricultural fairs, occasionally entering agricultural competitions.

Carnival returned in 1902, perhaps without a special African American exhibit.

For whatever reason, perhaps the distraction of a rapidly changing city in the progressive era, the whole Carnival didn’t return again until 1908, after local prohibition restricted beer and liquor sales in Knoxville, when it was different from its Gay Nineties origins, with the highlights a “decorated automobile parade” as well as a children’s vaudeville program, including a “doll parade.” The following year, 1909, a Fall Carnival organized by women’s clubs featured some events at the Lyceum building on Walnut Street downtown, including an art exhibition of the Nicholson Art League, but the main event was at Chilhowee Park, featuring a dog show, bowling, and dancing. It sounds like more of a Society event than the big free joyful melees of the Gay Nineties. In news reports, there’s no obvious mention of an African American exhibit.

Notably, though, the Negro Building did return in concept, in 1910. This time, it was an actual building, at Chilhowee Park for the Appalachian Exposition. Behind it was Knoxville College, its faculty and students, and it had a more specific theme of celebrating African American achievement. It returned for the big expositions of 1911 and 1913. That last one, the National Conservation Exposition of 1913, drew one million visitors across its two-month span. A few Knoxvillians who remembered the fascinating spectacle of the old downtown Carnival of the 1890s considered the Exposition to be a culmination. The Tennessee Valley Fair, always held entirely at Chilhowee Park, bloomed after all that, and features some of the elements of the October Carnival, like the displays of poultry and produce, and some performances—if not the regattas and extravagant parades and coronation balls.

– Jack Neely

(McClung Historical Collection)

2 Comments

Fantastic read! Thank you for your efforts!

Wonderful article about an event I’d never heard of, nor realized was on-going for so many years! Thank you, Jack, for this interesting read. Looking forward to the Williams House Tour on 11/16, Wednesday, next week!