Part of the lore of the 1982 World’s Fair, then and now, was that little ol’ Knoxville had the gumption, or arrogance, or naivete, to put on a world’s fair. The Wall Street Journal’s “scruffy little city” moniker, casting doubts on Knoxville’s aptitude to host a party that big, was just one of a series of condescending insults from journalists around the country. Time called Knoxville a “backwater.” Newsweek described us as “nondescript.” Forbes called Knoxville “undistinguished.” The Times of London noted we were “not so much sleepy as comatose.” Knoxville was a substantial city of about 180,000 with a habit of understating or even denigrating itself in a way that was convincing even to other mid-sized Southern cities. The Herald-Leader in Lexington, Ky., a city that had only recently grown a little bigger than Knoxville, described “little old Knoxville, that sleepy slowdown spot on the way from Kentucky to points south.” The Nashville Tennessean described Knoxville as if its own readers had never heard of it: “an unknown, uncelebrated town … that few outside Tennessee knew existed.”

Much of the press about the fair did not describe the insights the exposition shared and the real wonders it showed, favoring opportunities to remark, with humor, about how bizarre it was: for an ostensibly undersized, mediocre city to have anything to do with a global exposition. That’s the central part of the myth of the 1982 World’s Fair. Knoxville having anything to do with a world’s fair was a joke, and newspapers and magazines across America tried to find different ways to join in the fun.

But how weird was it, really? The planners of the Knoxville International Energy Exposition didn’t often refer to the city’s history. But in fact Knoxville already had dozens of connections to world’s fairs long before 1982.

Some Knoxvillians were at least thinking of world’s fairs by the time of the first one in history: the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. Knoxville was indeed an undistinguished little backwater then, with maybe 2,500 residents, no railroad yet, and just a tiny regional college, struggling and barely there. But we had a couple of weekly newspapers, and they occasionally referenced the big London fair. People here knew about it. Products introduced at Queen Victoria’s fair were available in Knoxville soon afterward.

The London fair may have inspired Knoxville’s very first fair, an 1854 event known as the State Fair of the Eastern Division. Probably our closest thing to a Crystal Palace was the new glass factory. It was on the river, along the modern-day greenway, probably just east of what’s now the marina. It featured prize-winning produce, a horse show and a plowing contest, but also locally manufactured products, from baby carriages to a freight car, beer (I wish we had some more detail about that)—and, significantly, the best work in local marble, a remarkable local resource, most of the world didn’t know much about yet.

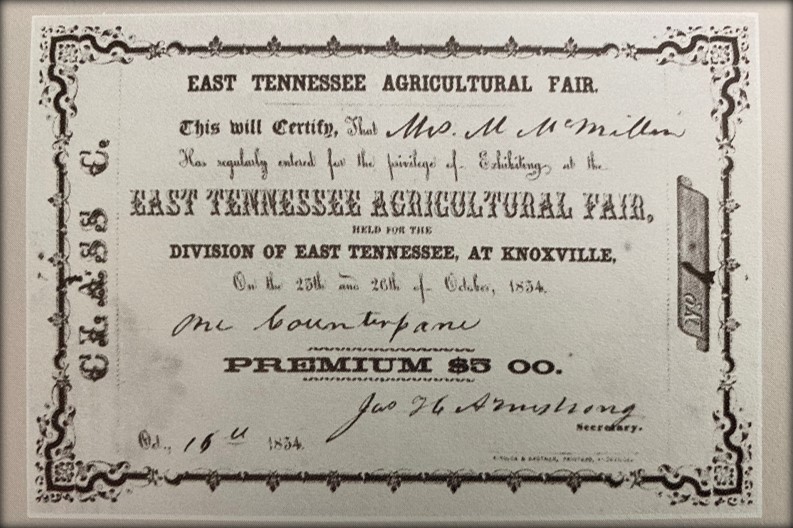

Exhibitor’s Certificate, East Tennessee Agricultural Fair, 1854 (from “Meet Me at the Fair” by Stephen Ash.)

Marble played a starring role in America’s first world’s fair, the United States Centennial Exposition of 1876, held appropriately in Philadelphia, 600 miles northeast of Knoxville, and by then easily accessible by passenger train. Many Knoxvillians made the trip, including a promising young grain dealer and miller named J. Allen Smith, who had not yet perfected the flour he would call White Lily. Traveling there together were brothers Frank and Calvin McClung; both were just young merchants, but both would, for unrelated reasons, one day have a museum and a collection, respectively, named for them. German-born orchestra leader Gustavus Knabe was there, and when his family’s Baltimore-based piano business won top prizes at the fair, our Maestro Knabe used that fact to advertise them in his new home of Knoxville.

But the big Knoxville celebrity was marble. Early marble tycoon George M. Ross, who had recently supplied much of the marble for Knoxville’s Custom House, was in Philadelphia for the fair.

American minerals were a big part of that fair’s showcase of wonders. Tennessee marble, previously little known, awed visitors, drawing rapturous commentary in newspapers accounts from across the nation. A newspaper in Rutland, Vermont, a state already famous for marble, had to admit that Tennessee marble was comparable. At the Philadelphia World’s Fair, the Knoxville Marble Company took top prize for colored marble. By the end of the year, they were getting contracts for architectural marble as far away as California. Over the next 40 years, major monuments on New York and Washington would be clad in East Tennessee marble shipped out of Knoxville.

Of course, the city most associated with world’s fairs is Paris. Considering the City of Light is more than 4,000 miles away from Knoxville, it’s remarkable that we have several connections to those world’s fairs, too.

The Exposition Universelle of 1878 was famous for in-person demonstrations from America’s young inventors, Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, as well as the unveiling of the head of the Statue of Liberty, France’s gift to the United States, eight years before its installation in New York. Representing the United States at the fair were several official commissioners appointed by President Rutherford B. Hayes. One of them had been mayor of Knoxville.

Peter Staub, originally from Switzerland, was the local developer who had already completed Staub’s Opera House, Knoxville’s most popular auditorium of that era. He crossed the Atlantic several times in his career, serving as both Swiss consul in America and American consul in Switzerland, but serving as the president’s commissioner at a Paris World’s Fair must have been a high point. Not long afterward, this former Paris world’s fair commissioner was elected mayor of Knoxville a second time.

The Paris exposition of 1889 is the one remembered for its theme structure, the Eiffel Tower, the first World’s Fair theme structure that was tall and permanent. Like its direct descendent, the Sunsphere, it was both loved and hated.

Several Knoxvillians attended that one, too, including University of Tennessee’s new professor of chemistry and metallurgy, Dr. Charles E. Wait. He had an international reputation, and in fact became a Fellow of the British Chemistry Society in London, a rare American to earn that distinction. He spent several weeks in Europe that summer, making connections and gathering ideas for UT. He said he used what he learned in Europe in the planning of UT’s new Science Building, commenced soon after his return, and completed in 1892. An unusually extravagant Victorian building on the otherwise staid Hill, the new building might be said to have possessed a touch of World’s Fair flair.

It was torn down 75 years later, in 1967. History’s always spotty, and though Dr. Wait was an internationally recognized chemist, his name is probably best remembered by historians for his pioneering support of organized athletics. UT’s first on-campus football field, established in 1908, was known as Wait Field—which itself is remembered mostly as the outmoded field replaced by Shields-Watkins in 1921.

Among major world’s fairs, Chicago took its turn in 1893, with the Columbian Exposition, arguably the most influential world’s fair in American history. It’s richly described in the nonfiction bestseller The Devil and the White City, which describes the enormous exposition as the backdrop for a bizarre string of real-life serial murders.

Buildings at the Columbia Exposition, Chicago, 1893 were an inspiration for the expositions in Knoxville, 1910, 1911 and 1913.) (Wikipedia.org)

Representing Tennessee at that exposition was one Thomas Lanier Williams II, a Knoxville politician from a once-wealthy family. He lived at the Vendome apartment building on Clinch Avenue, and later on Henley Street. His proposal to create a pavilion devoted to East Tennessee apparently came to naught, but he spent months in Chicago before and during the fair as one of two commissioners from Tennessee (another prominent Knoxvillian, merchant Rush Strong, for whom the colorful downtown alley is named, attended as an alternate). Today, Williams is best known as the grandfather of his namesake, playwright Thomas Lanier Williams III, better known as Tennessee Williams.

It’s long been claimed that Cal Johnson, who after emancipation became a rare African American business tycoon, but loved horses above all, owned thoroughbreds who raced at the Chicago fair. That’s plausible, if hard to prove: it was the height of his horse-training acumen, and Johnson’s horses fared well at several regional races in 1893.

Kin Takahashi, the Japanese student who introduced football to Maryville College, and arguably to East Tennessee, went to Chicago to work with the Japan pavilion, only to find that his own Japanese had gotten rusty during his years in America.

The East Tennessee Land Co., based in Harriman but with strong Knoxville associations, won the Chicago fair’s first prize for bituminous coal—but thanks to overinvestment and the Panic of 1893, was bankrupt by year’s end.

The lead designer for the Chicago World’s Fair’s grounds was the elderly Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park and Biltmore’s gardens in North Carolina. Olmsted was also in Knoxville during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair period, working on a project known today only in a few allusions in letters to and from UT president Charles Dabney—who also attended the Chicago fair. (Olmsted remarked on one occasion that the food in Chicago was dismayingly expensive compared to Knoxville.) What Olmsted was working on here is still a subject of speculation among historians, with Circle Park one contender (now on UT’s campus, but then a residential park), but Knoxville was also planning a much more ambitious park on the bluff tops across the river, accessible via a cable car, like something in a world’s fair. Whatever Olmsted’s local project was, it was probably doomed by the Panic of 1893, America’s worst depression before 1929.

However, associated with Olmsted’s ideals was the City Beautiful movement, a deliberate attempt to promote cities as not just functional and prosperous but beautiful places to live, with the belief that beauty can promote moral health and good citizenship. The Chicago fair made it a major theme. It was a new idea in America, and in fiscally conservative Knoxville, which had never created a city park of any size, it made a stir. The hubbub of idyllic fair-era Chicago, where Lincoln Park was a beauty spot, inspired the name of the new residential development on the streetcar line on the north side of Knoxville. The name of Knoxville’s Lincoln Park was announced in April 1893, days before the opening of the fair.

Most significant was that Knoxville became home to its own City Beautiful society, led by wealthy women, many of whom had attended the Chicago fair. Knoxville, which had never had money or space for public parks, was creating them. Luttrell Park, a privately owned park, popped up almost immediately after the big fair, in 1894. Small, urban Emory Park (now Emory Place), followed in 1905. By then, a Public Park Association was raising the flag, and in 1910, with express reference to Chicago’s progress, Knoxville’s City Beautiful League led efforts to found new parks. Those efforts resulted in real successes in the early 20th century, especially at Caswell Park and Tyson Park.

Far-away Paris held still another world’s fair in 1900, extolling electricity, diesel engines, motion pictures, and the art nouveau movement. Knoxville had an unusual presence in that one, too.

Knoxville civic leader Mary Boyce Temple, later hailed as a founder of preservation in Knoxville, was a never-married Vassar grad who devoted her life to causes. Governor Benton McMillin appointed her as a commissioner to the Paris fair, representing Tennessee. She was remarkable, as a woman holding that post, at a time when American women could not even vote. But she wasn’t the only Knoxvillian with some authority at that fair.

UT President Charles Dabney served as a member of the “Jury of Awards,” judging scientific and technological exhibits. We don’t know whether he recused himself when he surveyed the work of UT alum John Bogle Cox, an engineer who set up an innovative railroad display there. And George Washington Ochs, former Knoxvillian and brother of New York Times publisher Adolph Ochs, was there putting together the Times edition covering the exposition.

Dabney would later make a public presentation about the 1900 Paris fair on Knoxville’s Market Square, presenting “beautiful stereopticon views” of Paris. About 400 Knoxvillians attended that December show. It was perhaps a rare chance for Americans to hear a world’s fair juror offer his first-person observations of that big Paris exposition, accompanied with glowing images, in the most public place in downtown Knoxville.

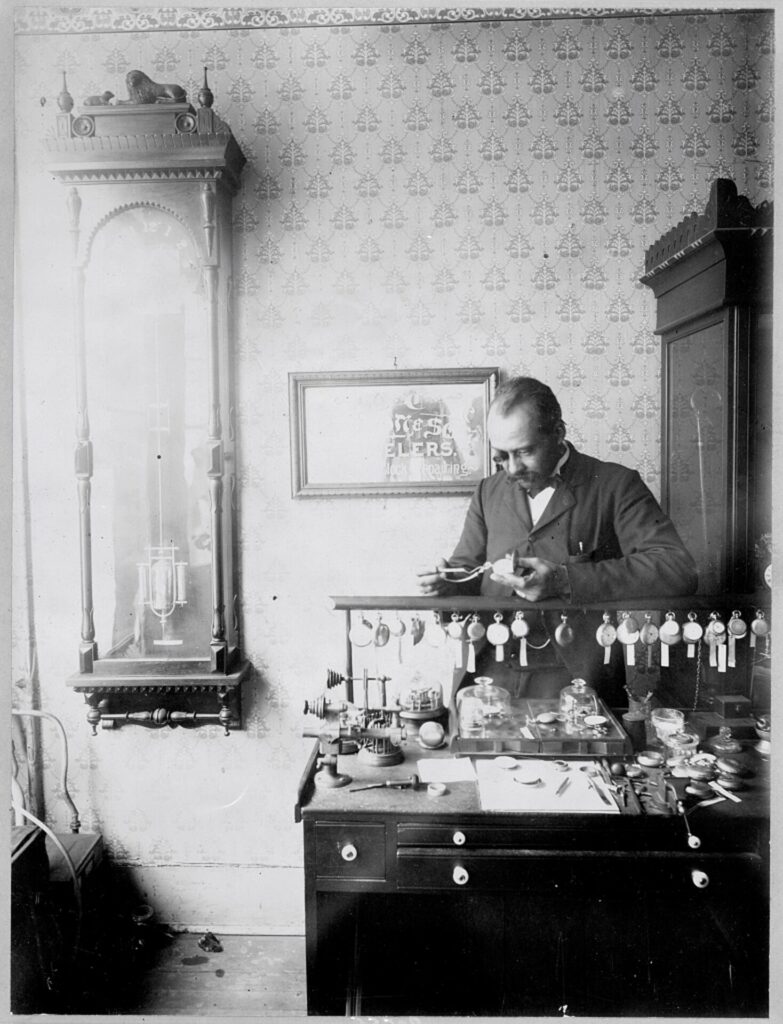

However, our most remarkable connection to the 1900 Paris Exposition may be that Knoxville was not just the home of some people involved in it, but, for once, Knoxvillians were actually the subject of an exhibit. That exhibit, installed at the Palace of Social Economy, was called “the Exhibition of American Negroes,” and it was assembled in part by young African American intellectual W.E.B. Dubois. Europe had little knowledge of Black people in America, and Dubois and his allies wanted to present images of professional and successful people. Knoxville, which had a substantial Black population, and the business-minded town perhaps offered more opportunities than some other cities, yielded several images of African Americans that presented them as the equals of Europeans. One subject was successful jeweler Charles C. Dodson, who was shown both at work and with his family posing in their stylish Victorian home on Patton Street.

Helping assemble photographs of Black people in Knoxville were teacher Charles Cansler and teacher and journalist Joseph Trigg, who was then serving as city alderman.

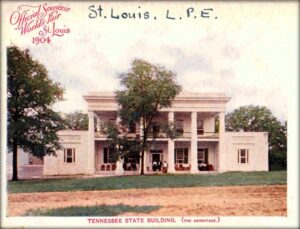

Four years later, another world’s fair opened closer to Knoxville than any other, in St. Louis, a fair better remembered than many today, thanks in part to Judy Garland and Meet Me in St. Louis. It was known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, and unlike previous world’s fairs, it had a Tennessee pavilion. Involved in promoting it was a young Knoxville pharmaceutical executive, David Chapman. It’s unlikely that he had anything to do with the final decision, to make Tennessee’s first pavilion in a world’s fair a scale replica of Andrew Jackson’s home, The Hermitage, with Old Hickory’s elderly granddaughter there to lead tours. In years to come, Chapman would be involved in Knoxville’s own expositions, and later still, he led the movement that became the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

At the St. Louis fair, a Knoxvillian wouldn’t have to walk far to see familiar faces.

UT professors were involved in the Agricultural exhibits there. Knoxville promoters were handing out tens of thousands of copies of the illustrated booklet, Progressive Knoxville. The C.B. Atkin Mantel Co. was there, claiming to be the biggest mantel company in the world.

Mary Boyce Temple, former commissioner for the Paris world’s fair, spent several weeks at the St. Louis fair, and was one of only 32 women nationally to be chosen as a member of the fair’s Jury of Awards.

Brown Ayres, then a professor at Tulane, already famous in New Orleans for his exhibitions of electrical technology, had led the organization of both the New Orleans and the Louisiana exhibits at the fair. It was during the fair that he accepted a call to become president of UT. Hence Ayres Hall, which was within view of the 1982 World’s Fair, is named for a leader of exhibits at the 1904 World’s Fair.

As had been the case with the Chicago fair, the St. Louis fair was so popular among East Tennesseans that Southern Railway added extra trains, at special rates, to ferry folks to and from the big party. Despite its delights, the 1904 St. Louis fair is associated with East Tennessee’s worst transportation disaster in history. On Sept. 24, just east of Knoxville, two passenger trains, one with passengers on their way to St. Louis, one with passengers coming home from the fair, collided at New Market. At least 56, probably more, were killed, and more than 100 injured, many of them seriously.

***

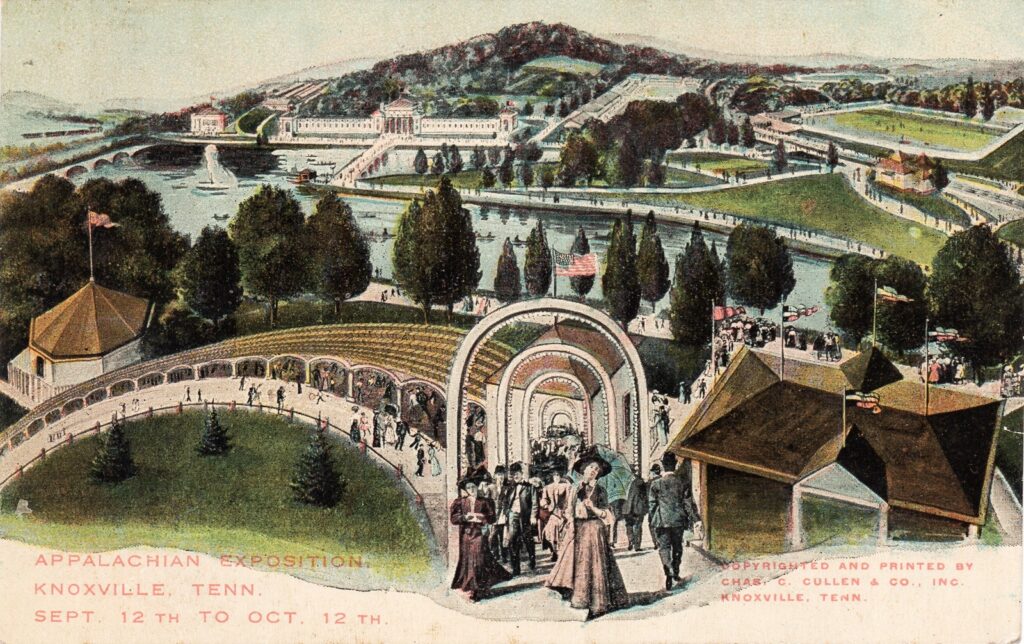

Perhaps it was Knoxville’s familiarity with several world’s fairs that gave the city the confidence to mount some large expositions of its own: The Appalachian Expositions of 1910 and 1911, and the larger National Conservation Exposition of 1913. The buildings erected for all three expositions at Chilhowee Park resembled the “White City” architecture at Chicago in 1893.

Teddy Roosevelt attended one of the Appalachian expositions, and befriended another attraction, early silent cowboy star Tom Mix. The 1910 fair also saw the first regional exhibition of airplane flight, featuring a race with a dirigible and an automobile. It’s not much of a stretch to consider that the movement to found a national park in the Smokies coalesced through the energy of the exposition era, especially the National Conservation Exposition. Several of the allies who were most vigorously involved in founding the park in the 1920s, including Ben Morton, David Chapman, and Jim Thompson, were young men in leadership positions at those big expositions at Chilhowee Park. Those big fairs, all concerned with issues around conserving our natural environment, may have had a major indirect legacy.

Also thickly involved in the expositions, especially the big one in 1913, was Mary Boyce Temple. Former commissioner of the Paris exposition of 1900 and juror of the 1904 World’s Fair, she knew how it was done. She gave speeches, led several welcoming committees, and was chairman of at least three different theme days at the big Knoxville fair: Daughters of the American Revolution Day, Panama Day, and Peace Day.

Believe it or not—and for whatever it’s worth—the 1913 Knoxville fair has made a long Wikipedia list of global world’s fairs. “World’s fair” is an American term, and has no official definition, but is usually considered to be a big exposition with a relevant educational purpose and significant international participation. Although the National Conservation Exposition of 1913 hosted no international pavilions, it offered an extraordinary variety of exhibits and events, from technological to artistic, with a “Negro Building” that served as an exhibit of African American achievement, and nationally well-known speakers, including Booker T. Washington, Helen Keller, William Jennings Bryan, and Gifford Pinchot. Its reported one million visitors over its two-month span makes it comparable in size to some officially recognized Bureau of International Expositions fairs, like one in Berlin in 1957. Somehow the prospect of hundreds of thousands of people coming to Knoxville for a big, interesting exposition of new ideas and products and culture didn’t seem to strike America as all that absurd in 1913. Dozens of newspapers across the country described it, and few if any expressed surprise or consternation about Knoxville’s aptitude to host a big fair. The Brooklyn Eagle hailed it as “the First of its Kind,” and remarked about Knoxville’s interesting historic sites, including the ruins of Fort Sanders and Parson Brownlow’s famous home—both of which vanished in the following decade.

If the NCE wasn’t a world’s fair, it bore a family resemblance to one. But after a world war, a couple of nasty riots, an epidemic or two, and the new wonder of radio, and the founding of a big national park nearby, Knoxville forgot about it. Later, some national historical sources about big expositions questioned whether Knoxville’s National Conservation Exposition ever even happened.

Moreover, sometime after World War I, Knoxville seemed to lose its intimate relationship with the world’s expositions. They were no longer familiar, planned by people we knew, but faraway events covered by the broadcast media, remote from us and maybe too sophisticated for our kind. Knoxville was sometimes affected by world’s fairs, but world’s fairs no longer seemed to involve Knoxvillians as much as before.

***

The Depression year of 1933 saw a second world’s fair in Chicago, the Century of Progress exposition, and even if it didn’t stir as much excitement and participation in Knoxville as did the one 40 years earlier, it would prove to have a few surprising influences on Knoxville’s future.

Among those who attended was an ice-cream entrepreneur named Hattie Love. Her visit made the papers at the time because she was president of the Knoxville chapter of the Federation of Professional Business and Professional Women’s Club. Five years later, she would become the first woman elected to Knoxville City Council, and known for a progressive agenda.

If you had attended that fair, you’d likely have hear the public-address announcer, a young University of Illinois graduate with a strong Chicago accent. His name was Lowell Blanchard, and he announced at the fair both in 1933 and when it was held over in 1934. Soon after that, he would move to Knoxville and create a live-radio tradition called the “Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round”—which over the next quarter century launched dozens of careers, especially in country music.

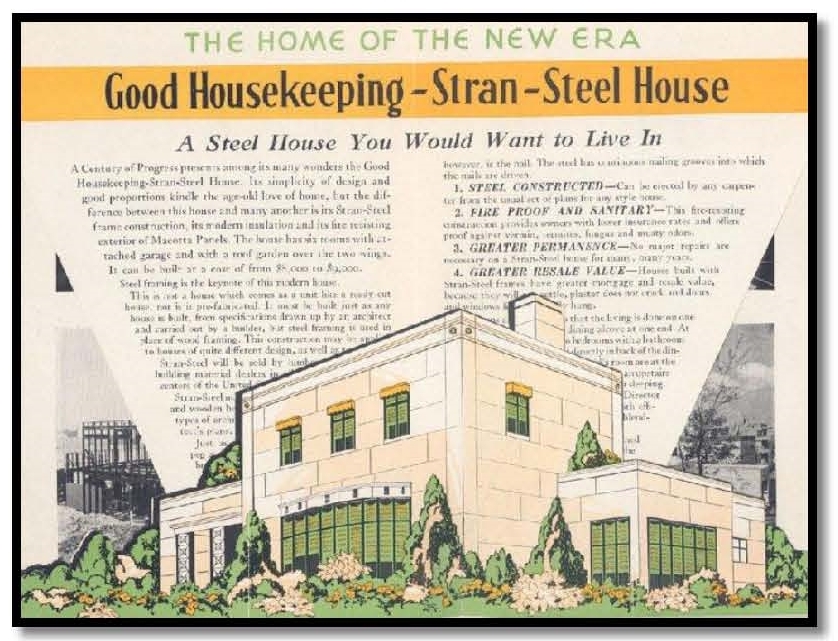

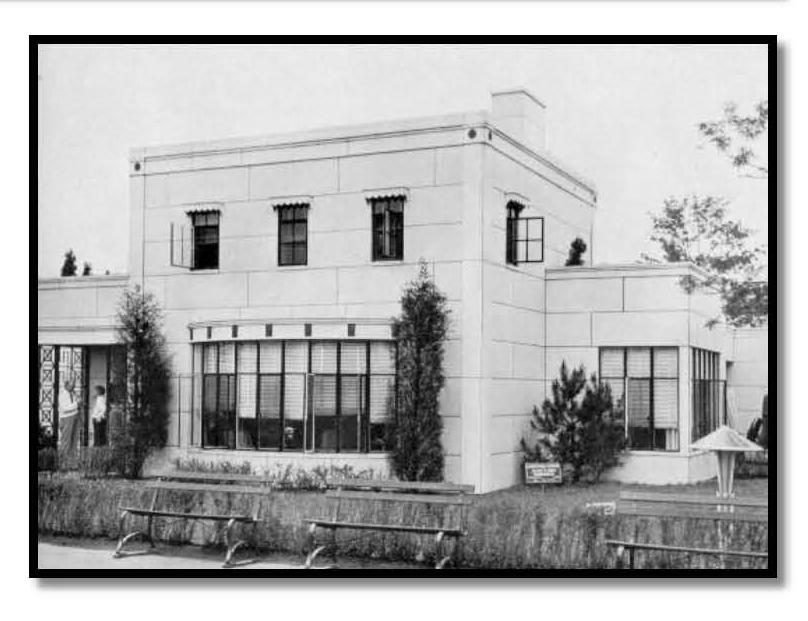

That fair also inspired some Knoxville architecture. Elizabeth Dunlap, perhaps Knoxville’s first female architect, was best known for her landscape designs, but also designed a few houses, and found particular inspiration in the new modernist architecture on display at that fair’s Homes of Tomorrow exhibit, especially the flat-roofed Stran-Steel House. She obtained a basic plan for the “art moderne” home. Completed in 1935, her World’s Fair-inspired house on Sequoyah Hills’ Scenic Drive was arguably Knoxville’s first modernist house. Its owner, architect Mark Heinz, who lives there with his family, has recently restored it as a landmark.

The Good Housekeeping – Stran Steel House from the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. (Courtesy of Mark Heinz.)

Another young architect helped design some of the 1933 fair’s wonders. An Illinois native, Hubert Bebb had studied architecture at Cornell before he drew designs for the Chicago fair. But he was a lover of mountains, would eventually settle in Gatlinburg, where in 1955 he became famous for designing what looks like a world’s fair theme structure, the ultramodernist viewing tower at Clingman’s Dome. Later, as an elderly man, he came to Knoxville to work for another world’s fair, 49 years after his first. Bebb is credited with the basic design for what became the Sunsphere.

New York’s 1939 World’s Fair became a legend as the most futuristic of world’s fairs, with its iconic Trilon and Perisphere, and for giving millions of Americans their first glimpse of something that would change their lives, and, some suspected, end the need for world’s fairs: Television.

Despite its emphasis on a utopian future, the big fair nonetheless was also among the first to emphasize American folk music, demonstrating the burgeoning interest in country music in the 1930s, as it had been developing in several cities, including Knoxville. A reported 14 “mountaineer dancers, singers, and instrumentalists” from the Southern Appalachians were there. (It’s not clear that any of them were Knoxville radio performers.)

World War I hero Alvin York, the Fentress County native who was often seen in Knoxville, gave a historical talk, “The History of the Long Hunters.” (It was two years before the Gary Cooper movie, Sergeant York, made him an even bigger star.) Opera diva and Oscar-nominated Hollywood star Grace Moore, who’d spent part of her childhood in Knoxville and had recently performed at UT’s Alumni Auditorium, packed the Hall of Music in the first month of the fair, for a concert including work by Massenet and Bizet. And in that year when Neyland’s Vols were national contenders in college football, the Court of Sports included a large Tennessee banner.

The New York fair included a Tennessee exhibit, and there, Knoxville was reportedly the state’s only city that advertised itself, as boosters handed out an estimated 356,000 booklets promoting regional attractions, the new Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the even newer technological and architectural marvel, Norris Dam. It was perhaps the beginning of the mid-century era of Knoxville’s habit of promoting its regional, rather than municipal, assets.

The World War and its aftermath, and perhaps uncertainty of whether television would make world’s fairs obsolete, seemed to pause big expositions in America for a while. The idea returned in faraway Seattle, where a Madisonville-born UT grad, Sen. Estes Kefauver, spoke, acknowledging that his daughter has a job on the fair staff. Wilma Dykeman attended and wrote a couple of columns about it for the News-Sentinel. But for the most part, Knoxville had long since stopped paying as much attention to world’s fairs.

Knoxville did have a couple of surprising connections to the Montreal World’s Fair of 1967—or, more specifically, to its famous theme structure, the giant geodesic dome. One is that the dome was covered with 2,000 individual pieces of Plexiglas, 200,000 square feet in all, and according to a brief mention in the News-Sentinel, they were manufactured at Knoxville’s Rohm and Haas plant. The other is that its architect, Buckminster Fuller, was in Knoxville giving lectures at UT’s then-new College of Architecture in early 1967, just before the building’s unveiling, and was giving interviews to international press while he was here. Fuller returned to Knoxville more than a decade later to consult on a somewhat similar structure to be called the Sunsphere.

And in 1974, Spokane, Washington became the smallest American city ever to mount a world’s fair. Although few Knoxvillians attended that fair, it got some attention here. The day it closed, Stewart Evans, president of the beleaguered Downtown Knoxville Association, suggested that he might have an idea for what this half-forgotten city needed. If Spokane can do it, maybe Knoxville can, too.

To many, it seemed purely bizarre. Of course, by then, the Knoxvillians who had been intimately involved in world’s fairs in Paris and Chicago and St. Louis, as jurors, commissioners, industrialists, promoters, were long gone, and mostly forgotten. Knoxvillians didn’t seem to get around as much as they did in the era of railroads and steamships, and the city’s promoters had recently touted the city’s value in terms of hosting a sometimes pretty good college football team, and for its proximity to the Smoky Mountains and some nice lakes. For whatever reason, the world and even the region almost forgot about us. The Knoxville World’s Fair might have been less dumbfounding to the world if it had happened 60 or 70 years earlier.

Leave a reply