Some people and things you might have seen one century ago, at Christmastime

It had been a dramatic year, one that had seen perhaps the only racially prompted lynch-mob riot in American history in which the only people injured were white–and the subject of the lynch-mob action was freed for lack of evidence. In most ways, Knoxville was trying hard to seem modern, with the old college bigger than ever before, with close to 2,000 students, and looking much more impressive than it had a year ago, with brand-new Ayres Hall crowning the crest of the old Hill–and a real regulation football field, with bleachers on the floodplain to the south.

But even at Christmastime, baseball, both local and national, dominated the sports pages, with photos of Babe Ruth and Roger Hornsby. In fact, the first game played on Shields-Watkins, earlier in the year, had been a baseball game. On the east side, Caswell Park’s first season as home of the Knoxville Pioneers had proven a place too easy to hit a home run. By rearranging some tennis courts during the holiday season, the owners tore down the old right-field fence and built another one another hundred feet away, at 328 feet.

Meanwhile, a series of unseasonable tornadoes had struck the Deep South, along the lower Mississippi, killing at least 44, most of them African Americans in rural areas. The storm’s remnants brought no tornadoes, but unwelcome drenching rain to Knoxville on Christmas Eve.

Everything was changing, including the look of Christmas. Some old-school sorts still lit their Christmas trees with carefully placed candles, but downtown electrical stores were trying to get them to quit. “An Electrically Lighted Christmas Tree Can Do No Damage,” declared the Moses Electric Co. Children deserved to be able to “enjoy the perfect safety” of electrical Christmas lights.

Long discussed, two new national automobile highways were becoming a reality, and they were set to combine for 20 miles in Knoxville: the Dixie Highway and the Lee Highway promised to usher in an era of tourism unlike the train-dependent travel of previous eras.

More and more people had automobiles, though they were still mainly for the affluent. Even newer than cars were buses. More nimble and versatile than passenger trains, 1921 buses held just 15 passengers, but came and went on a frequent schedule for Maryville, Clinton, Dandridge, and a few dozen other towns. You could pick one up at the station on State Street.

Radio seemed just around the corner. Some people, especially boys and very young men, already had sets, and could pick up transmissions and broadcasts from other cities.

Jazz and blues were on records you could buy downtown, and represented the first time most white Americans had experienced real African American music, as blackface minstrel shows of the vaudeville era began to seem old-fashioned.

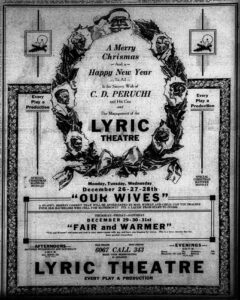

The year-old Riviera was Knoxville’s biggest movie theater, but only one of about a dozen theaters downtown. But there were still live theatres that featured shows more nights than not, notably the Bijou and the larger Lyric—which we used to call Staub’s.

The stock company Peruchi Players, run by the always lively Chelso Peruchi, the former circus acrobat turned director, were putting on Adam and Eva, “A Snappy, Breezy Comedy of American Home Life,” at the Lyric. At the Bijou the day after Christmas was Bringing Up Father In Wall Street, one of a series of musical comedies based on the popular Sunday comic.

At the cinemas, Get Rich Quick Wallingford, the movie version of the popular Broadway play, was at the Riviera; there was a Zane Grey western at the Strand, and a Hoot Gibson western at the Queen. All silent, of course.

Only because Christmas landed on a Sunday, when theaters were closed, entertainment was scarce on the 25th. The traditional Christmas holiday matinees were on the following day, the 26th.

The Market Hall was hardly 25 years old, but already seemed run-down and old-fashioned, and a few were already calling for it to be razed, as it would be a few decades later. That’s not to say it wasn’t very popular. Dozens of farmers’ wagons, both motor-driven and mule-drawn, surrounded it. Market Square was a “Great Bee Hive,” according to a headline in the Journal & Tribune, as a region’s worth of grocery shoppers were preparing for tens of thousands of perfect Christmas dinners. The Market Hall and nearby stores were filled to overflowing. Shoppers waited in the rain just to get inside.

Some shoppers from as far away as Kentucky and Virginia and North Carolina rode Southern or L&N trains into town to spend a few days at a hotel like the Farragut or the Atkin to shop at Miller’s and Arnstein’s and George’s. There were few places in the south with so many stores per acre.

Nationally, readers were closely watching the Fatty Arbuckle trial, wondering if the familiar funny man really could have murdered that young beauty at that wild party. Socialist Eugene Debs, who had spoken in Knoxville more than once, early in his career, was freed from prison where he had been held for three years on a sedition charge—during which he had run for president one more time, receiving over 900,000 votes.

Harry Daugherty, President Harding’s attorney general, offered a Christmas Eve message. “To all mankind, I wish a happy, healthful and hopeful Christmastime. Let us hold up our heads and be of good cheer. Let us love God and be grateful. Let us obey the laws of our country and let us obey the Ten Commandments.”

He was a figure known personally to several Knoxville Republicans. A little more than two years later, the same Harry Daugherty, under pressure from President Coolidge himself, resigned over allegations of corruption concerning his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal.

Several affluent families were establishing winter quarters in St. Petersburg, Fla. A Journal reporter said he knew of 61 notable Knoxvillians who were spending the Christmas holidays there, among them the energetic Chavannes lumber family—and N.E. “Whitty” Logan, the maverick Red Cross volunteer and Bearden-area real-estate promoter. (She apparently traveled separately from her husband, who’s not mentioned.)

But there were lots of interesting folks still in town, and it’s hard to think of the crowds of Market Square, without thinking of 1921 Knoxvillians you might run into, perhaps literally, if you made your way in.

At 56, Judge E.T. Sanford was a respected federal judge, working out of the Custom House, and one of those locals who knew Harry Daugherty. Two years later, largely thanks to Daugherty’s help, he’d be on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Roy Acuff was an 18-year-old Central High grad; not much of a musician yet, he was an aggressive athlete with a reputation for fighting.

Also 18 was a UT student from Madisonville named Estes Kefauver. About 30 years later, he’d be an influential U.S. senator making a credible run for the U.S. presidency, but in 1921 he was more interested in football.

Cincinnati-born Bertha Walburn, who had just turned 39, was a recognizable violinist and recent divorcee who was working toward creating a symphony orchestra in her adoptive hometown. That Christmas, she may have been part of the live music advertised as part of the Christmas dinner served at the Farragut Hotel.

Howard Armstrong was a charismatic 12-year-old street musician from LaFollette, a versatile kid who played both fiddle and mandolin, just becoming known up and down Vine Street. It was about 60 years before the first documentary about him.

At 42, Catherine Wiley, the brilliant painter who had introduced Knoxville to impressionism 20 years earlier, was still painting in her studio on White Avenue, less the center of attention than she used to be, and no longer painting in the bright sun-drenched tones of the turn of the century. She was prone to depression, and it was beginning to show in her art.

Beauford Delaney turned 20 that holiday season. No longer just the jovial shoeshine kid everybody liked, he was working as an assistant to elderly artist Lloyd Branson, in his Gay Street studio. But spirited Beauford was already developing a reputation as a modern sort of artist with his own style. For him, New York and Paris were still in the distant future.

Eugenia Williams Chandler was 21, married to a war veteran for about a year. Known to be an heiress from her father’s Coca-Cola investments, she was admired for her fashion sense, but had a reputation as aloof. She and her husband lived in a stylish apartment downtown then, but didn’t mix much. Her father had recently begun developing some riverfront residential property on Lyons View.

Charlie Barber and Ben McMurry, well-regarded architects in their 30s, were becoming known as talented and innovative revivalists, in an era when all young home buyers wanted their houses to look very different from their parents’ Victorians. They’d recently announced the addition of a younger third partner, Knoxville-raised, MIT-trained John Fanz Staub. But at age 29, Staub was already getting lucrative contracts for mansions out west, especially in rapidly growing Houston. He may not have known it yet, but he would never return to Knoxville except to visit, and occasionally design a house. He had just begun plans for his aunt’s house, the unusual English cottage that would be called Hopecote.

Cal Johnson, who lived downtown, was an old man of 77; though born into slavery, he had become a successful businessman and by 1921 even a philanthropist, and one who was happy to invite passers by to sit with him on his State Street porch and swap stories.

Any of those remarkable people might have jostled you and each other as they shopped along crowded Gay Street sidewalks, or muscling their way onto Market Square. It’s safe to say that every Christmas crowd every year includes some people who will one day be remembered as legends. That’s one of the lessons of history: we never really know what’s going on until decades later.

Santa Clauses were all over the place, even in the Jewish-owned department stores, even in the churches. It would be a daunting challenge to count how many Santa Clauses were afoot in downtown Knoxville in 1921.

Prof. John R. Bender, who had been UT’s football coach for three recent seasons, led a Christmas Tree Committee that with the help of the Salvation Army and Associated Charities—a sort of step great-uncle of United Way–would distribute at least 1,000 gift bags to needy children, who gathered near the big freshly decorated Christmas tree on Market Street, and waited for Santa himself to appear at 7 p.m. on Christmas Eve to do the distributing. In each bag was candy, nuts, popcorn, apples, oranges, raisins, and chewing gum. Each item was likely more appreciated in 1921 than it would be today.

And over at the School for the Deaf, in the building later known as LMU’s law school, Santa Claus actually emerged from an artificial chimney with gifts for 222 students from across the state. This Santa knew sign language, and responded to thanks conveyed by the students.

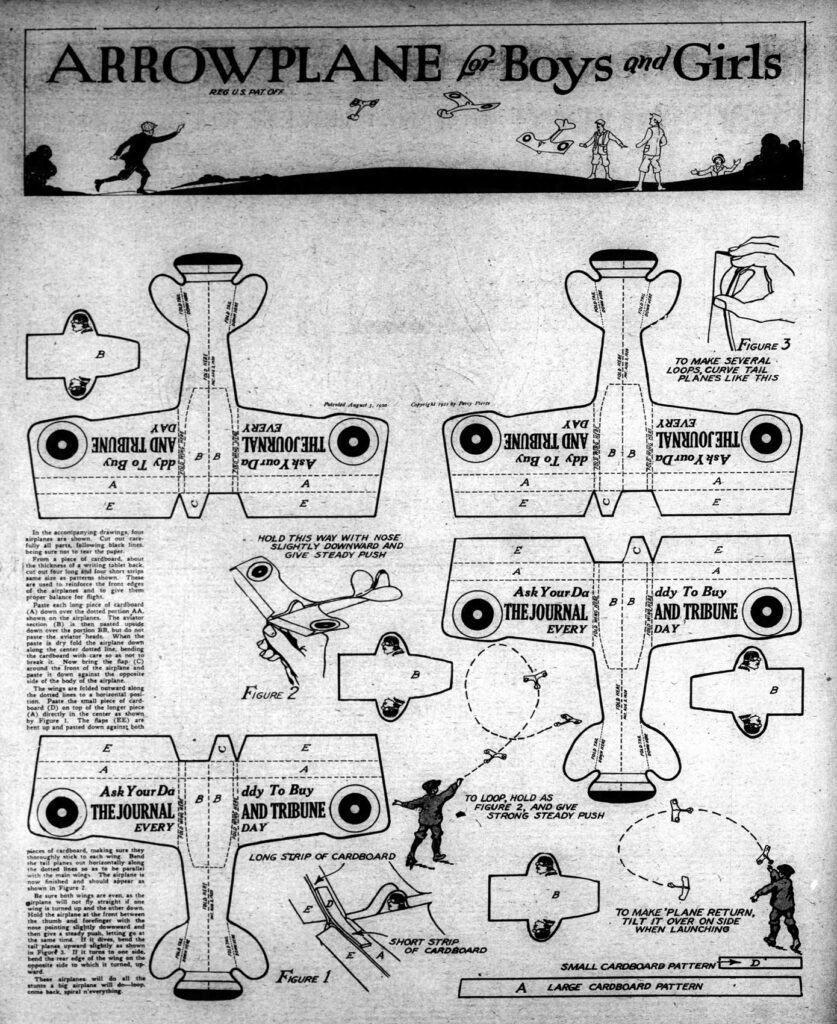

The Journal and Tribune, still run by octogenarian Union veteran William Rule, made his Christmas Sunday newspaper a must-read, with long fiction, lots of sports and society news, the Katzenjammer Kids—and, taking up one whole page on Christmas Day, a gift for all kids, an “Arrow Plane,” or the pattern for one—just need scissors, paste, and a strip of cardboard, and you have a toy monoplane.

Theaters were closed on Sundays, by law or custom or both, but some restaurants were open. Hotels traditionally advertised a Christmas Day feast, and though they weren’t as fancy as they had been in the 1890s, several obliged, including the relatively new Farragut Hotel, which served from noon to 9 p.m., with live music in the early evening, likely Bertha Walburn’s string quartet—she was a regular. The Farragut’s specialty was simple, half a chicken, broiled or fried.

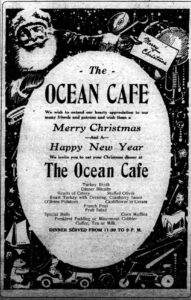

The Ocean Café, run by the Greek-immigrant Regas Brothers, offered a traditional Christmas Dinner of turkey and dressing and cranberry sauce from 11:30 until 9:00. The desserts are what make a 1921 Christmas dinner seem different: the Regases offered a choice between “President Pudding”—now obscure, one old recipe makes it sound like a sort of custard—and Mincemeat Cobbler.

A few churches offered Christmas Day or Christmas evening services, like Church Street Methodist—it was still on Church Street in 1921—which offered a choral extravaganza, with a big choir and selections including Handel’s Messiah. There was a religious side to Christmas, but in 1921, you saw it mainly inside the churches, not in the streets.

In the past, Christmas Day in Knoxville was often known for murder. It wasn’t like that in 1921, but violence came from the modern world itself.

People went on Christmas-Day drives in their crazy new cars. One car full of young men flipped on Maryville Pike in South Knox County. One young man, the driver, was killed, another seriously injured, with his scalp torn off his skull. On the north side, another car in the Greenway area of Broadway stalled on a train track, and was demolished, but only after its six occupants had gotten to safety.

Perhaps the most surprising Christmas tradition of 1921 was the annual Motorcycle Hill Climb. It took place on the day after Christmas, four miles north of downtown, on the slopes of Sharps Ridge, near Broadway. Spectators took the streetcar up to witness riders of Harleys and Indians from several states battle their way up muddy Greenway Hill.

But the holiday still got a bit out of hand, as it had back in the ’90s. Alcoholic beverages were both illegal and easy to find. A couple of days after Christmas, City Judge John L. Greer faced a crowded room of defendants, all from incidents on Christmas Day. “Much of it had about it the reminiscent odor of a wet Christmas,” remarked the tongue-in-cheek reporter.

“Many of the defendants bore the mark of conflict … almost invariably the testimony showed the [holiday] parties had broken up in fistic arguments. In a few cases brass knucks and other effective weapons of hand-to-hand combat had been used.” However, the reporter found it remarkable that “There was little rancor” among those “who had only two nights before been hammer and tongs at each others’ throats. The following was typical of the post-Christmas spirit,” claimed the reporter.

“Oh, there wasn’t nothing to it, judge,” said one. “He just picked me up and threw me across the stove, and I heave a stove lid at him. Just what you might call a friendly little argument.”

Judge Greer fined them all $10 each. He was known to be strict, often lecturing defendants, and taking no excuses. But at 23, “the boy judge,” said to be the youngest judge in Knoxville history, was sometimes the object of fun among newspapermen. He later got out of the legal business, and invested in Kern’s Bakery, when it was a major industry, becoming an executive and board chairman. But that’s not what made him nationally famous, more than a half a century later. It had something to do with his memories of childhood, watching horse races at Cal Johnson’s half-mile track near Chilhowee Park. The same John L. Greer who was fining Christmas revelers in 1921 would be the owner of an impressive racehorse named Foolish Pleasure, who won the Kentucky Derby in 1975.

See, look at any crowd, at Christmastime, and you just never know.

Jack Neely, December 2021

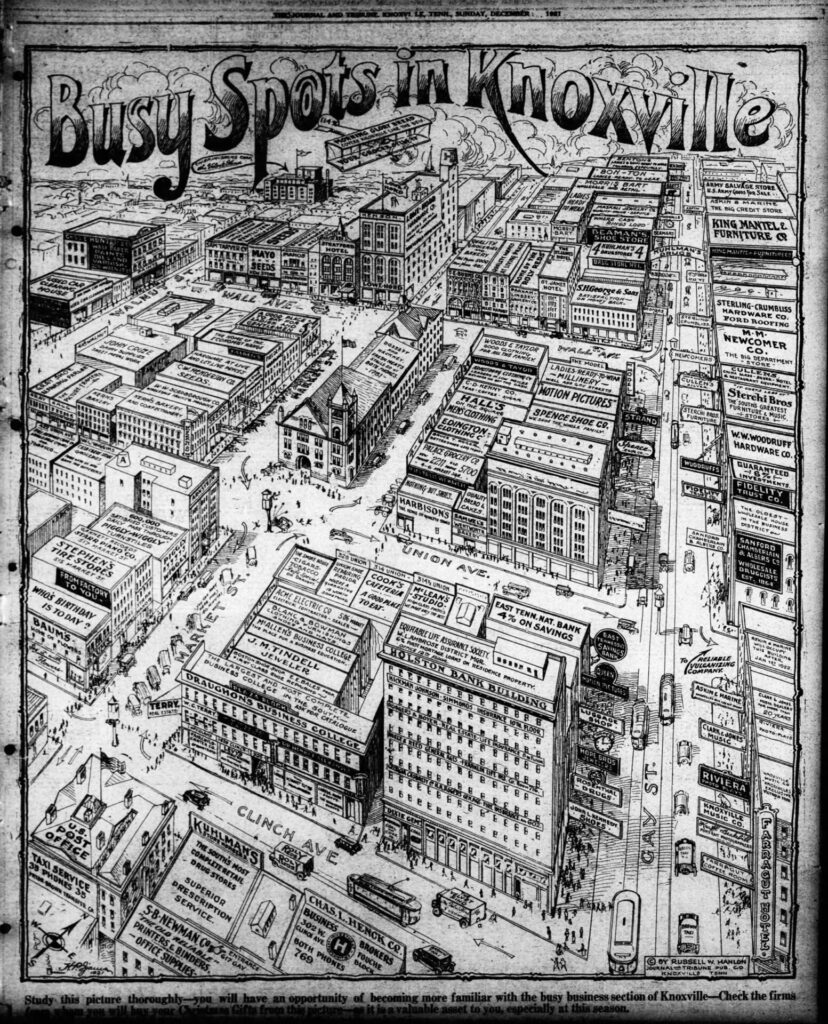

The Knoxville Journal included this illustration by commercial artist Harry Ijams, of downtown vendors in 1921 and during the Christmas season added these words, which may be a little hard to read at the bottom: “Study this picture thoroughly –- you will have an opportunity of becoming more familiar with the busy section of Knoxville –- Check the firms from who you will buy your Christmas gifts from this picture – on it is a valuable asset to you , especially at this season.”

The Knoxville Journal included this illustration by commercial artist Harry Ijams, of downtown vendors in 1921 and during the Christmas season added these words, which may be a little hard to read at the bottom: “Study this picture thoroughly –- you will have an opportunity of becoming more familiar with the busy section of Knoxville –- Check the firms from who you will buy your Christmas gifts from this picture – on it is a valuable asset to you , especially at this season.”

A reimagining of this illustration is available in large format canvasses produced by Joe McCamish at https://knox1921.com/products/busy-spots-in-knoxville-1921. You can stop by the Museum of East Tennessee History to view an example or check out the story on WVLT.

Leave a reply