And the Electrical Wizard of St. Charles Avenue

Ayres Hall is a century old this year, and maybe, finally, it’s as old as people always thought it was. Actually, some newcomers, innocent of the challenges of the frontier era, see the university’s founding date of 1794 and figure it was built about then. It does look very old, especially from the bottom of the Hill.

Ayres Hall wasn’t supposed to be named Ayres Hall. But that sounds good. It may seem a perfect name for a prominent building high on a hill, up in the Air: Aeronautically high, with a tower where an eagle might be comfortable building an Aerie. For a university that often drew criticism in a region where many working people and even legislators considered higher education pretentious, a real challenge for several administrations, it might also seem a symbol of putting on Airs.

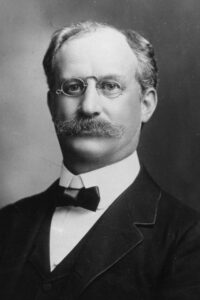

But when Dr. Brown Ayres announced the project and did much to make it possible, he mentioned no name other than “administration building.” He was a modest, reserved fellow, and had the practical mind of a scientist. He chose names taxonomically, to describe what sort of things they were.

Today it’s called Ayres Hall, and Professor Ayres is a worthy honoree, and a much more interesting fellow than the average guy whose name winds up on a building. Even in the city where he’s most honored, most people don’t know that he played a role in ushering America into the modern era.

It’s not that Professor Brown Ayres is unknown. He’s routinely name-checked as the president between Dabney and Morgan, and most handy information about his time at UT describes him mainly as an effective administrator who, during his 14 years and four months at UT’s helm saw the beginning of significant state funding, the establishment of the medical college, the separation of the colleges of liberal arts and business, and improvements in both UT’s academic status and its enrollment. In Knoxville, even among historians, he’s mentioned almost entirely for what he did for UT, achievements mainly financial, political, and organizational in nature.

But all that happened after he was 48 years old. It seems as if his young and middle years, and his main identity when he accepted the call to Knoxville, has been forgotten—so much so, that in recent years there’s been a wise-guy suggestion that Ayres was so obscure that his invitation to be president of UT was accidental.

In 1904, it’s true, someone had nominated Cincinnati’s Howard Ayers for the presidency. The zoology prof had been fired after a brief and chaotic tenure at the University of Cincinnati just before that school hired UT’s Charles Dabney to straighten things out. Wags have enjoyed speculating that it was a spelling mistake that brought Brown Ayres of Tulane to Knoxville.

In fact Howard Ayers never got the full board’s approval for UT’s top job, and it seems unlikely any university would have offered him an administrative role. (Ayers left academia that year and became an elevator executive.)

Brown Ayres, by contrast, was much better regarded, a respected scholar and administrator. His name was known in academia, but also even to Knoxville newspaper readers—partly because he may have already introduced Knoxville to a new thing called Radio.

As a young man, he did a lot of that, spreading the word about what the future would be like. In New Orleans, where he spent most of his adult life, he was the genius who demonstrated the electrical wonders of his age to the Crescent City.

Born in Memphis in 1856, Brown Ayres moved to New Orleans when he was still a kid, and showed an aptitude for publishing. While still living in New Orleans, when he was only 15, he attended Virginia’s Washington & Lee, and while there started a triweekly paper with a great name: The Rockbridge Baths Review. An 1871 article in the Lexington Gazette, reprinted in the New Orleans Republican, in August, 1872, hints at his destiny. “Browny is a rare genius. His home is in New Orleans. How the petted little fellow learned the printing business is a mystery … Printing is but one of his many accomplishments. He erected with his own hands a telegraph line along our streets, put up the instruments, and taught some amateur operators among his friends, the students. He touches the key with rare dexterity. He is not a mere mechanical operator, but an expert electrician, and was employed by the Professor in the University to explain to a class the reasons of a telegraph. He carries with him a little French phonographic instrument, and takes ‘views’ when the scenery pleases him. With all his genius, he is as frolicsome as a kitten, and gentle as a girl.”

So he was already lecturing at the college level at age 16. The “phonographic” reference is startling. It was before Edison’s invention of the phonograph. If it’s not a typo of “photographic,” it’s likely a reference to a French innovation called the “phonoautograph,” which records visual images of sound on paper.

In New Jersey, at Hoboken’s Stevens Institute of Technology, Ayres received his first degree, in 1878. He later earned a Ph.D. from that institution. It may have been while he was a student at Johns Hopkins in the late 1870s when he developed a friendship with a slightly older Scot named Alexander Graham Bell.

Ayres had been experimenting with the telephone as early as the summer of 1877, soon after Bell’s famous patent was announced. A tiny item in a newspaper called The Spirit of Jefferson remarks that the 21-year-old Ayres was communicating between two points in western Virginia, 12 miles apart: Lexington and Rockbridge Baths, about where he had been experimenting with telegraph wire at Washington & Lee. A couple of surviving personal letters from Bell suggest that Ayres assisted Bell himself in at least one public demonstration of the world-changing device in New York in 1878.

According to Ayres family sources, Bell offered young Ayres a job, but the young student declined. Bell was interested in business and profits, but Ayres was a man of ideas. He favored a career in academia.

In 1880, Ayres landed work as a professor of sciences at the University of Louisiana in New Orleans, where he had lived before. Ayres was already there in 1884 when the struggling school became the private Tulane University.

His early teaching reflected his fascinations with the various wonders of the era of electricity. Soon after Edison’s creation of the first practical light bulb, Ayres was corresponding with the inventor himself, ordering the peculiar glassware to demonstrate Edison’s invention in New Orleans. Two handwritten 1881 letters from Edison to Ayres survive, both concerning the critical issue of how to ship such fragile devices.

Most professors never get mentioned in the newspapers, but in New Orleans Ayres became a very public intellectual, demonstrating the wonders of the modern world to the public, as if it was his mission. He gave lectures about light, electric and natural, raising philosophical questions about how and whether they were different. He also talked about electric motors, then coming to the fore in an ever-widening pageant of uses.

Ayres and his Virginia-born wife, Katie, lived in a big house in the Garden District, on St. Charles Avenue, the most beautiful boulevard in America.

St. Charles is famous for its columned mansions and live oaks. Today it’s also famous for its electric streetcar. In 1888, when the city was just beginning to consider installing an electric streetcar system, it was Ayres who explained how it could work. Ayres was still there a few years later, when the electric St. Charles streetcar became the best way to travel the mile and a half from his home to his college.

The mustachioed professor was also known as a musician, a director of the city’s Choral Symphony Society–and as a host. The Ayres St. Charles home, between Milan and Berlin Streets (before the latter was renamed Gen. Pershing Street), was described as “the center of a delightful social life and … a favorite place for literary people visiting the city.”

As a popular public speaker in New Orleans, Ayres was once described as “pleasant and gossipy, but extremely lucid and instructive.” He often employed slide shows, using an “electric lantern” as early as the 1890s, and helped his fellow faculty members with the device; he may have been the only guy at Tulane who could handle it.

The New Orleans Electric Society met in a hall on Perdido Street, and Ayres was often its star attraction, giving lectures about the nature of electricity and light itself. He described new concepts like alternating current and Nikola Tesla’s electromagnetic wave theory. In 1896, Ayres reportedly became the first in the Crescent City to create an X-Ray image, using Wilhelm Roentgen’s brand-new technology. While acknowledging the important role Thomas Edison played in electrical progress, he sometimes criticized his contemporary for taking credit for the work of others.

Perhaps he gave Edison credit for the phonograph, one of the many new devices that fascinated Ayres. He experimented with it in New Orleans, making recordings. Considering it was the era of legendary cornetist Buddy Bolden and the elusive moment that gave birth of jazz, we can only speculate what the professor might have recorded, and what happened to those recordings.

Among his many national honors was his role on the “Jury of Electricity” at the globally historic Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Ayres later lectured and planned an exhibit on Education in the South at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

In 1894, he became Dean of Tulane’s College of Technology. He later helped found the Louisiana Industrial Institute, leading a building campaign there. It’s now known as the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Ayres’ name was on the cornerstone of that campus’s first building, the old Main Building, later known as Martin Hall–until it was demolished in 1963. He later became interim president of Tulane.

Concerning Ayres’ early career, resume details and lists of honors seem mundane in contrast to his public persona on St. Charles Avenue. New Orleanians associated Brown Ayres with incredible wonders. He was intellectually curious, always fascinated with the next new thing.

Sometimes the new things were in outer space. Ayres predicted a comet and took photographs of a 1900 solar eclipse that earned national attention. His Renaissance spirit even got him elected president of the Louisiana Society of Naturalists, even as he admitted he was not exactly a naturalist. He explained that he was stimulated by what he could learn from them.

Ayres predicted in 1901 that “airships” were a “probability,” two years before the Wright Brothers’ first flight. He also predicted that solar power would be difficult if not impossible to make practical. He was fascinated with the prospect of gleaning energy from coal without combustion. In April, 1902, he set up a practical demonstration of Marconi’s “wireless telegraphy” system, successfully sending a radio signal between two buildings on Tulane’s campus, 200 yards apart.

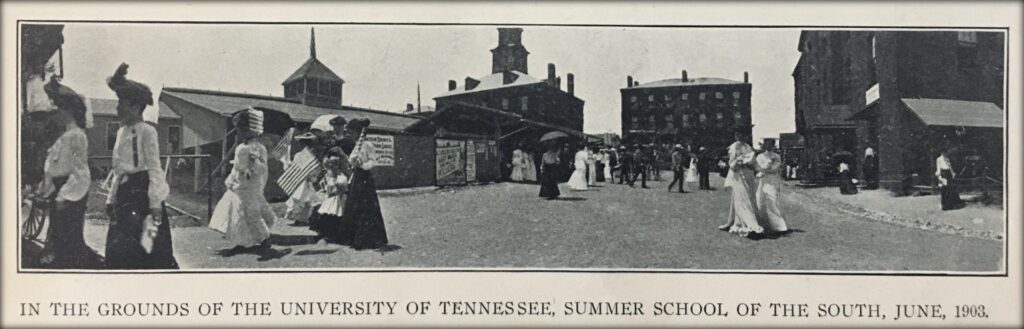

At the height of his fame in New Orleans, Ayres’ curiosity brought him to Knoxville during the era of its Summer School of the South. Perhaps poorly named—historians often assume it was UT’s summer semester—the Summer School was an extraordinary development in UT’s history, a weeks-long, eclectic Chautauqua-style festival of seminars on the Hill drew thousands of educators from across the South every summer. It was because of the Summer School that the electrical wizard of St. Charles Avenue spent the month of July, 1902, in Knoxville. On July 11, he dazzled crowds with demonstration of “wireless telegraphy”—probably similar to the demonstration he gave in New Orleans three months earlier. Was it the first demonstration of radio in Knoxville history?

That summer he also lectured on theoretical physics here, remarking on the relationship between light and electricity, speculating on whether they were more or less the same thing. He suggested that the human eye was “an electrical instrument.”

He was back on the Hill in 1903 at least briefly in the summer of ’03 to give a lecture about teaching physics.

UT President Charles Dabney resigned in 1904 to take the helm of the University of Cincinnati. During the 1904 lecture series, the 48-year-old acting president of Tulane was in Knoxville as he had been the previous two summers, staying at the Hotel Imperial on Gay Street, when he was tapped to be president of the University of Tennessee. For reasons of his own—climate is said to have been one draw, and proximity to his wife’s family in Virginia was another–he accepted the job.

News reports suggest that Tennesseans knew little of his electric reputation in New Orleans: just that he was a highly esteemed academic with multiple honors—that’s how they described people in those days, by listing their honors–and that he had been born in Tennessee, an important issue to some conservative legislators.

Ayres moved to Knoxville with his big family: his Virginia-born wife, Katie, and eight children. It might be interesting to research what they thought of the place, in contrast. Ayres moved from St. Charles Avenue into the “elegant residence” reserved for the university’s president on the southeastern slope of the Hill, a rambling Victorian with a view of the still-wild Tennessee River.

Ayres became UT’s president right away, but wasn’t formally “inaugurated” until the following April, in an unprecedented ceremony downtown. An academic procession of scholars with gowns and mortar boards formed at the Woman’s Building on Main, and marched across Gay Street to Staub’s Theatre. Until the 1930s, UT had no building adequate to hold a large crowd and regularly used the old opera house and vaudeville palace for graduations and other exercises. UT’s shortage of appropriate buildings was likely a deficiency that Ayres noted.

But Staub’s was packed. On the committee that welcomed him to UT was Judge E.T. Sanford who almost 20 years later would be a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Others present included former president Charles Dabney, U.S. senator and former governor James B. Frazier, and Prof. Ebenezer Alexander, the classical scholar who as former ambassador to Greece assisted in launching the first modern Olympic Games.

Ayres was president of UT for a little more than 14 years. Though still interested in new scientific developments, Ayres found little time to become the evangelist of science he had been in New Orleans as a young man. In Knoxville, he seems to have been necessarily preoccupied with politics and fundraising, spending his time on receiving lines and train rides to Washington and Nashville and sometimes Memphis, trying to knit the state together and expand UT’s presence.

Although his own personal background in the physical sciences would have earned him a place in the previous administration’s emphasis on practical and vocational education, Ayres still loved literature and music, and wanted his UT to be a citadel for the liberal arts, too.

He maintained the Summer School’s liberal series of lectures that had first drawn him to the Hill, despite some controversy during his administration that it was an inappropriate distraction for a practical public university. He usually spoke at the event, praising its founder, Philander P. Claxton. He and Katie often hosted receptions for the event’s extraordinary array of speakers, which during his era included William Jennings Bryan and Chicago reformer Jane Addams.

During his period, the Summer School of the South began touting its “Fine Music Festival” to the public. Previously just an aspect of the Summer School, during Ayres tenure the Music Festival took on a life of its own, advertised without reference to the Summer School of the South, and featuring big performances, including performers like the entire Cincinnati Orchestra.

Ayres reorganized UT’s college system and raised standards for admission, but at the same time increased enrollment, bringing it past 800 for the first time–partly by raising UT’s status in the world of universities. As a result of Ayres’ initiatives, even the University of Berlin began respecting a UT degree.

Local student Clarence Brown began attending the same year as Ayres’s grand inauguration. The future MGM director–he would become known in 1920s Hollywood for his technical innovations–earned two degrees in engineering during Ayres’ tenure. They knew each other. Brown was a tech kid who was on the Hill for five years—one of his degrees was specifically in electrical engineering—but Brown’s girlfriend at UT happened to be Elizabeth Ayres, the president’s daughter. They apparently parted when Brown left town in 1911.

Another student during Ayres’ tenure was a mathematics major and sometime dancer named John Fanz Staub, grandson of the Swiss immigrant who had built the theater. A quarter-century later, Staub would be a famous architect building mansions in Texas. (One of his best early creations, the English cottage-style house known as Hopecote, designed for his aunt when Melrose was still a residential area, is now part of UT’s campus, and used by the university for visiting dignitaries.)

Still another UT student during that time was Joseph Wood Krutch, who would soon be famous as a critic and author. For such a small college, UT under Ayres’ leadership produced several creative people of national renown–though he didn’t live to hear of their accomplishments.

Occasionally, the old Wizard of St. Charles would peek out. He’d occasionally speak to engineering classes, and in 1908, Ayres hosted a demonstration of several new inventions and innovations to the Manufacturers and Producers Association convention at UT’s Estabrook Hall, remarking to the assembly that the university should work more closely with industry.

In early 1915, Brown Ayres proved he could still hold forth on subjects other than buildings and budgets when he spoke at the Joseph LeConte Scientific Society, meeting on the Hill, on the ambitious subject “The Regeneration of the Universe.”

His large family was mostly healthy and accomplished, but that summer, his son Samuel Warren Ayres, a 28-year-old professor of German at Miami of Ohio, was found dead, sitting in a grove of trees near Fort Sanders, a victim of an apparent drug overdose. Like his father, Warren was a curious and enthusiastic student, a UT grad who had studied further at Johns Hopkins and Heidelberg, Germany. He had been ill. It was assumed that he had been working too hard.

Although in middle age Ayres seems to have shelved his enthusiasm for public demonstrations of electrical wonders, he did launch a wartime program of studying and teaching “radio telegraphy”—four years before Knoxville’s first radio station. In early 1918, during the war, he supervised the installation of four wireless stations on the Hill, for the benefit of 14 students studying “radio electricity.” Ayres explained how to use “tonal codes” to protect transmissions.

World War I almost knocked the wind out of the college, with so many Volunteers joining the fight, but during that time, he initiated a course in automobile repair specifically to address the wartime need for that skill.

Ayres was happy to support athletics, in general—but in 1918, when a UT student died as a result of an injury sustained in a regular-season game with Vanderbilt almost three years earlier, Ayres expressed his anger and grief with a suggestion that the university should reconsider its decision to sanction football. “I feel as if I would like never to hear of a football game again,” Ayres said. However, within months, he was approving the university’s new regulation football field, a major engineering project on an expansion of the campus, soon to be known as Shields-Watkins.

In early summer of 1918, Ayres traveled to Washington to discuss federal funding for wartime building: an armory building, whose wartime need was obvious—UT had welcomed training troops to its small campus–but also an “administration” building to replace three old antebellum buildings on the top of the Hill.

Despite the amount of time he spent on it, politics was not his forte. By most accounts, Ayres was a cordial and fair administrator, but not one to create warm friendships easily. He relied on others who were heartier hand-shakers than he was. Chief among them was one of his chief hires, Canadian-born entomologist Harcourt Morgan. Largely with behind-the-scenes help from Morgan, UT landed an appropriation from the traditionally stingy state legislature of almost a million for building projects, an unprecedented amount.

The initiative was exciting, but it prompted a reaction that may well count as Knoxville’s first concerted preservationist campaign: to save, by whatever means, Old College. The 1828 brick building on the hilltop was the university’s first permanent building, the centerpiece of three antebellum buildings, flanked by East College and West College. No one claimed that Old College was a triumph of architecture, but the brick building had a central tower, and was a distinctive and perhaps authenticating landmark for what was already one of the nation’s older state universities. The campaign was not just local. The Chattanooga News stated a widely held belief that Old College was “the first college building west of the Alleghenies … it has rare historic and architectural value.”

Old College had been there through the Civil War, when it was hit multiple times by Confederate shells, many of them fired from the bluff across the river, aimed for Fort Sanders or the smaller Fort Byington, the smaller Union fort on the Hill. Its scars were never repaired, making it all the more beloved to some alumni who in 1918 began raising money to save it. Its damning flaw was that it stood in the ideal spot for an iconic new building. But some engineers believed Old College could be saved with an expensive move backwards, to take its place among the other buildings around the quad, perhaps as a sort of shrine to UT’s history, a place for portraits and trophy cases.

To design the new building, Ayres turned to the Chicago firm of Miller, Fullenwider and Dowling, in particular the principal, Grant Clark Miller. Then in his late 40s, the architect (1870-1956) had some experience with Knoxville, and with UT’s peculiarly lofty part of it. In 1910-1911, when in partnership with older architect Normand Smith Patton, his firm was called Patton & Miller, he had been to the Hill to plan the Carnegie Library on western slope. (Later remodeled, it’s now known as the Austin Peay building.)

Patton & Miller specialized in public and college libraries, designing more than 100 of them, most of them in the Midwest, substantial-looking buildings of brick and stone.

Miller had split with Patton when he returned to Knoxville several times in 1914-1915 to work with established local architect A.B. Baumann designing, on another hill, the new Lawson McGhee Library. They built it on the slope of Summit Hill to the north of Market Square. Grant had worked with the library’s board, including Mayor Sam Heiskell, Col. L.D. Tyson, Prof. George Mellen, prominent attorneys John Webb Green and James Maynard, and merchant-historian C.M. McClung. Historians might envy Miller’s acquaintance with an impressive cadre of Knoxville’s cultural leadership. Three of them were published authors, one a war hero and future senator, one a founder of the McClung Historical Collection that still bears his name. Several of them were connected to UT.

After leaving Patton’s firm, Miller stayed in Chicago to form the new firm of Miller, Fullenwider, and Dowling. He was back in Knoxville before the end of the year 1918—just weeks after the crest of the Spanish Flu epidemic, in fact—to discuss Dr. Ayres’ proposal for an impressive new building.

When asked to design a building that would preserve the antebellum relic, Miller replied that to site the building properly, the old one would have to be torn down. Its presence, he thought, would be “detrimental” to his vision for the site.

It would be a dilemma for Dr. Ayres that January. Ayres had said Old College would have to be torn down, but the university’s board opposed that view, seeking to save one of the oldest public-college buildings in the South. “In nearly every mail,” alumni sent letters to Ayres insisting on keeping Old College somehow. It reached fever pitch that January 11. Ayres was able to take a break from the hubbub to attend an educational conference in Baltimore.

At that conference, the ever-impressive Ayres was nominated president of the American Association of Land Grant Colleges, which includes most of the best public universities. He declined, citing his pressing duties at UT. Instead, he accepted the role of first vice chairman of the national organization.

The same day as that announcement, 26-year-old architect John Fanz Staub published an open letter urging all UT alumni to demand that Dr. Ayres save Old College. By then, Staub was a decorated war hero who had seen aerial combat and earned two degrees from MIT, soon to become a nationally famous architect. But in 1919 he presented himself was a UT alum who had studied math in in the hilltop’s old buildings. “Its simplicity, stability, and dignity are expressive of the character and ideals of the sturdy pioneers who crossed the Alleghanies and redeemed a wilderness,” Staub wrote of the old building. “The alumni are not contending for the preservation of an unsightly thing simply because of sentimental attachments, but are asking that we save the purest and most representative piece of architecture on the hill—the one piece which stands the supreme test of beauty—harmony with its environment.”

Staub’s eloquent statement is remarkable in retrospect; he was well on his way to becoming arguably Knoxville’s best-known native architect.

According to a Chattanooga News writer who was sympathetic to the preservation issue, the question of whether and how to save Old College “had been occasioning Dr. Ayres much concern.”

***

Some reporters had noticed that the stress seemed to be getting the best of Ayres, who may have been suffering physically. It was widely assumed that by the time he got the building projects well underway, perhaps by 1920, he would retire.

Arriving back in Knoxville from Baltimore, Ayres was ill. It didn’t seem serious. Some of his faculty, including young engineering professor Nathan Dougherty, were suffering from influenza, leftovers of the flu pandemic that had been so deadly two or three months before.

Soon, the 62-year-old university president was feeling better. He considered pleas for a formal UT basketball team, while trying to promote his own idea of a music department, to be equipped with a chapel or auditorium within the proposed new “main building.” That January, a description of it captured Knoxville’s imagination. It would also include 42 classrooms, 42 “professors’ studies,” two large lecture halls equipped to show motion pictures, a bookstore, and two “literary society halls,” and an “attractive rest room for young ladies who do not live on the campus.”

Ayres’ socially active wife, Katie, who was president of the Faculty Women’s Club, was planning a program about the Red Cross, featuring women who had worked with the organization in Europe during the war.

By some accounts, Ayres last visit to his own office in Old College was to meet with architect Grant Miller.

On Monday, Jan. 27, Ayres fell ill again, by some accounts, with “acute indigestion.” The following morning, he died at his home on the Hill. Some reports blame the stomach problems; others stated it was “a heart affection.”

His grand vision of a building was still purely on the drawing board. Into the middle of 1919, battered, beloved, beleaguered Old College still stood at the crest of the Hill.

Miller was now working mainly with the board of trustees, and soon with the new president, Ontario-raised and educated Harcourt Morgan, a specialist in entomology. Morgan made the call to name Ayres Hall.

The campaign to save Old College raised a lot of money, but not nearly enough to move it safely and securely out to a subsidiary role. (It appears that no campaign ever coalesced to save its two antebellum peers, East College and West College.)

As preservationists were bemoaning the shortcomings of their fundraising campaign, an inspection disclosed that many of the interior bricks in Old College were inferior, so inferior that they might not even be valuable as salvage. All three buildings were torn down in 1919, not long after Ayres’ death.

At least one of the good bricks from Old College was formally installed by a young student early in the construction of the Administration Building.

Only two days after Ayres’ death, an anonymous “U.T. Student” who had known Ayres personally publicized a plea to name the proposed new building “Brown Ayres Hall.” The name “Ayres Hall” emerged into general use more than a year later, when it was under construction.

By then, the project was paired with an agricultural building, also to be designed by Miller. Conceived as a sort of little sister to Ayres Hall, it would much later be known as Morgan Hall, honoring President Ayres’ agriculture-minded successor.

Ayres Hall was completed over a period of months. (About five years ago, architectural scholar Justin Dothard published an excellent study of its unusual architectural style—despite the gargoyles, it’s not Collegiate Gothic, but Elizabethan Revival—as a graduate thesis called “About Face.” It’s handy online.)

Ayres Hall finally opened for business in 1921.

Grant Miller remained a sort of architectural consultant on retainer for almost a decade after the Ayres Hall project was completed. In 1925, he presented UT with a campus plan. Many of Miller’s individual building proposals were ignored, and none of the Hill’s later buildings echo the “Elizabethan revival” motif of Ayres. But the top of the hill otherwise resembles his general ideal, with the circle of buildings served by circular driveways. (Miller had proven he was no preservationist, but one of the few buildings he favored keeping in the plan was 1898 Estabrook Hall, which the university demolished about five years ago.)

Miller was occasionally seen on campus as late as 1930, working with the firm today most associated with university’s more traditional “collegiate gothic” architecture: Barber & McMurry (still in business today, but lacking the &). In particular, Miller was a consultant on the design of Hoskins Library, a project sharply curtailed from its original vision, but still elaborately gothic in style. Miller’s best known work is almost certainly Ayres Hall.

Katie Ayres remained prominent in Knoxville social circles until her own death, 20 years after her husband’s. They’re buried together at Greenwood Cemetery on Tazewell Pike.

It’s a coincidence worth noting, considering that the young Ayres was fascinated with radio—that Ayres Hall, his namesake, hosted some radio history. WUOT, one of America’s first generation of public radio stations, and today Knoxville’s oldest station, first broadcast from Ayres Hall in 1949, 30 years after the death of the man who may have introduced radio to Knoxville back in 1902.

Ayres Hall is now a century old, as old as many people have assumed it always was. It’s older than Old College was when it was torn down.

People are often best remembered for what they did when they were young and energetic and open-minded. Ayres is the opposite. Most thumbnail biographies remember him almost entirely for what he did in Knoxville, in late middle age, in putting a very small college on the path to becoming a great university. Not his electric youth, when he was connecting one of the South’s oldest cities with the wonders of a future century.

by Jack Neely

Leave a reply