This summer marks the 130th anniversary of a civil-rights convention that was decades ahead of its time—and helped introduce some charismatic Black leaders of the future.

In 1891, a national conference of African American civil-rights activists, recently organized in Chicago, chose to have a meeting in the South. For this second meeting in their history, the Afro-American League came to Knoxville.

For many of us, the phrase “Afro-American” harks back to the 1960s and ‘70s. But it originated in the late 19th century, promoted by New York journalist T. Thomas Fortune, who wanted to remind Black America of its origins in Africa. He co-founded the Afro-American League in 1890.

Within a year, that national organization organized volunteer chapters in 18 states. But in 1891, the organization chose Knoxville as the site of its second national convention.

Their visit offers a glimpse of a city and a movement at a critical time, in ways both unsettling and inspiring.

Knoxville was a concentrated and rapidly growing industrial city of about 25,000: a medium-sized city by 1891 standards. With a population density about four times as many people per acre than today, the concentrated city had a distinctly urban character. About 28 percent of Knoxvillians were African American—more than one in four–a much higher proportion than today, partly because the city’s narrowly defined boundaries included no suburban or rural areas.

Knoxville’s 10-member Board of Aldermen had included Black members in the recent past, and would in the future, but that year, it appears the city council was made up entirely of white men. The mayor was a German immigrant, the popular baker Peter Kern, who had arrived in America as a refugee.

Knoxville was unusual among American cities in that it employed some Black policemen and firemen.

One of Knoxville’s proudest businesses was the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad, a major interior network that connected the nation to most of the South. Three years later, J.P. Morgan would buy it and make it part of the new Southern Railway, but in 1891, it was still headquartered in Knoxville.

Railroads were a critical nexus for civil rights in America, and things weren’t moving in the right direction. One by one, states had been adding new laws, segregating the races on passenger cars.

***

The Afro American League’s first meeting had been in Chicago. Its founding president was Rev. Joseph C. Price, the schoolteacher and Methodist pastor who had founded North Carolina’s Livingstone College. As a charismatic speaker, his reputation was more than regional. He had spoken in Methodist conventions in England, and the London Times dubbed Price “the World’s Orator.”

Rev. Price may have influenced the choice to come to Knoxville for the national organization’s second meeting. He had spoken here several times before, even to biracial crowds at Staub’s Opera House or the courthouse, sometimes drawing almost as many white attendees as African Americans. Price had, in fact, conducted the dedication service for Logan Temple, the enormous AME Zion church downtown, in 1886.

The landmark frame church stood at the corner of Reservoir—later known as Commerce—and Marble Alley, an African American residential street that lay between State and Central. Completed just five years earlier, with an impressive tower, Logan Temple was the largest African American church in town. With seating for 1200-1500 people, there were claims it was the largest church building of any kind in Knoxville, and the third-largest Black church in America. It was described in the white press as “an ornament on our city” that “reflects credit upon our colored people.”

And in 1891, it hosted the annual convention of the Afro-American League.

In the organization, Price’s more secular counterpart was T. Thomas Fortune. Born into slavery in Florida, slim, bespectacled T. Thomas Fortune rose to become editor of the New York Age, America’s best-known African American newspaper; he developed a reputation as a civil-rights intellectual and militant activist. Fortune had been to Knoxville before, too, once speaking at Staub’s to Knoxville’s literary societies. At that biracial gathering in 1889, Fortune had received applause when he demanded an end to segregation at Knoxville’s train station waiting rooms.

***

Five days before the national meeting in July, 1891, Knoxville’s activist leadership met at the courthouse to organize their own Afro-American League chapter. Young educator Charles Cansler was secretary. Chapter attorney was groundbreaking politician and respected lawyer William Yardley; at age 47, he was older than most of this younger generation of activists.

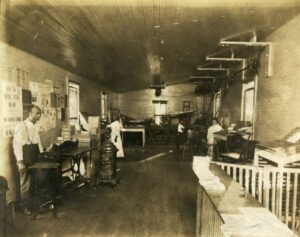

The office of The Gleaner, an African American publishing house on Central Street, was “profusely decorated with flags and bunting,” featuring a big sign saying, “Welcome Afro-American League.”

The convention’s timing might have seemed less than fortuitous, but the railroad-segregation news gave them something to talk about. Tennessee had once gone its own way; in the late 1860s, Tennessee was considered one of the nation’s most progressive states for civil rights. By 1890, though, Tennessee’s once-bold Republican Party had begun to imitate the Southern Democrats with a white-centric platform. Just weeks before the convention, the Tennessee legislature added the state to the growing list of Southern states to legislate segregation of railroad cars.

As a result of either inconvenience or protest, only a fraction of the expected visitors arrived in time for the opening meeting.

Among those who did make it were another prominent leader, editor and educator from Augusta, Ga., R.S. Lovingood, dubbed the “Negro Seer” in a later biography—and W.H. Anderson, a Civil War veteran of the U.S. Colored Infantry who co-founded the civil-rights-oriented Detroit Plain Dealer.

By one account, about a dozen states were represented by delegates at the meeting. About 20 Tennesseans attended the meeting as delegates. In addition to “Squire” Yardley and Charles Cansler was James Mason, a former slave who had established the first school for African American deaf children—but was, in 1891, working as a policeman. Rev. Job Childs Lawrence was there; he’d been elected to Knoxville School Board in 1888, but was barred from taking his seat. Originally from Sevier County, Samuel R. Maples, a 31-year-old Knoxville city magistrate at the time of the convention, welcomed the convention to Knoxville.

Of all those who attended the Knoxville convention, the most famous today wasn’t even a delegate. She was a woman, and that may have been one reason she was not announced as one of the convention’s primary speakers.

***

Within Logan temple, a permanent arch over the speaking area declared: “The Best of All, God Is With Us”—they were the last words of Rev. John Wesley. Beneath it, the convention got underway. The morning of Tuesday, July 14, saw the most serious business. It included some intensive discussion about disturbing trends in America’s racial landscape.

The League promised to be law-abiding, and had begun as a non-political, multi-partisan sort of effort. One significant gesture they resolved to do in Knoxville was to strike the word “non-political” from their original charter. A year and a half after its founding the Afro-American League apparently observed a necessity to be political to accomplish its goals.

The delegates expressed concern about the “tendency of state legislatures to draw the color line by passing discriminating laws as to public conveyances, etc.”

However, concerning the persistent problems experienced by African Americans attempting to get loans for homes or businesses, they were heartened by the “establishment of banks by the colored people” of Washington, Richmond, and Chattanooga.

Read aloud at the convention was AAL’s constitution, which echoed some terminology of the American Revolution:

“The objects of the League are to protest against taxation without representation; to secure a more equitable distribution of school funds in those sections where separate schools exist; to insist upon a fair and impartial trial by a judge and jury of peers in all cases of law wherein we may be a party; to resist by all legal and reasonable means mob and lynch law whereof we are made the victims, and to insist upon the arrest and punishment of all such offenders against our legal rights; to resist the tyrannical usages of all railroad, steamboat, and other corporations and the violent or unlawful conduct of their employees, in State and Federal courts; to labor for the reformation of all penal institutions where barbarous, cruel, and unchristian treatment of convicts is practiced, and assist healthy immigration from terror-ridden sections to other and more law-abiding sections.”

That last line seems to foretell what would happen in the early 20th century, the escape of refugees to the industrial North known in retrospect as the Great Migration.

It sounds almost modern, and surprising for 1891—if perhaps also a little dispiriting, considering many of the AAL’s goals in 1891 are still the subjects of struggle 130 years later.

They went further still: “The objects of the League … are to break down color bars, and in obtaining for the Afro-Americans an equal chance with others in the avocations of life …. The objects of the League shall be attained by the creation of a healthy public opinion through the medium of the press and pulpit, public meetings and addresses, and by appealing to the courts of law for the redress of all denial of legal and constitutional rights; the purpose of the League being to secure the ends through legal and peaceable methods.”

Specifically the big AAL meeting condemned the nation’s new railroad segregation laws. “We are not able to command language sufficiently strong to characterize our condemnation of the separate car system as maintained in many of the states. It is a gratuitous indignity—an insult to our manhood, and we believe it to be a violation of constitutional and common law.”

And the convention denounced lynching as “one of the greatest evils which we are called upon to endure, and we feel that the time is ripe when this species of lawlessness should be stopped.”

***

Underlying the overall concerns was that the AAL were perceived to be a little too “brainy,” too intellectual, too ideological. One of their goals was to reframe their public perception to attract more people, and people tend to be political—to form groups and alliances to defeat other groups and alliances.

“We have to deplore the fact … that the race at large has not been brought to take a more active interest in our work. Believing that the general apathy has been caused by the nonpartisan feature of the constitution, we have modified the constitution … as to bring it more in harmony with the political aspirations of the race.”

Idealists who hoped to achieve progress without partisanship had been disappointed a few months before by the defeat of the Lodge “Force Bill,” which attempted to assure voting rights across the nation. It had narrowly passed the U.S. House, and President Harrison liked it, but in the Senate, it ran into opposition, even from Republicans anxious to deal with colleagues where the African American vote might constitute a threat to the status quo.

***

The most practical thing they did that day in Logan Temple was to elect officers. The choice of T. Thomas Fortune, of New York, as president for the term to come, was no surprise. The new secretary was W.H. Anderson of Detroit, the new treasurer L.W. Wallace of Milwaukee.

However, the new vice president of the national organization was less well known than the others. He was an impressive young attorney based in Knoxville. His name was John W. Hargo. A Wilberforce University graduate in his early 30s, Hargo was originally from Ohio, and had begun his law practice in Cincinnati. Moving to Knoxville around 1887, ostensibly for the health of his wife–a mixed-race woman who sometimes passed for white—he quickly became a prominent and trusted figure in the community, working closely with older attorney W.F. Yardley on murder cases, and serving on the financial committee of the Harrison and Morton Colored Club, which boosted the successful 1888 campaign of Republican Benjamin Harrison.

Of all the attendees at the 1891 convention, Knoxville’s most prominent member of the national Afro-American League would suffer the strangest fate.

***

A climax of the convention was an open “mass meeting” that evening, probably attended by more Knoxvillians than conventioneers. In contrast to the disappointing turnout at the meeting itself, it was a large crowd that packed Logan Temple that summer evening.

An unapologetically male group, the AAL was, by its own definition, “a national organization devoted to the special purpose of securing our full citizenship and manhood rights.”

One of the featured speakers was not listed as one of the delegates, perhaps because she was the wrong gender. But the men in charge let her speak, and her appearance gained some attention.

She was young, just two days before her 29th birthday. Her name was Ida B. Wells. She was a schoolteacher, journalist, and civil-rights activist who wrote for the Memphis-based Free Speech and Headlight. At the Knoxville convention, she apparently had a goal, to get the men to welcome women into the club.

The Journal & Tribune seemed impressed with her, even if they got her name wrong: “Miss Ida B. Mills of Memphis, in elegant language, told what women could do for the League. They did not intend to be idle, but would press on with their fathers and brothers.” (The same paper got her name right in another item the next day.)

Fortune gave the closing address, and the long and efficient first day ended with a choral singing of the vivid old abolitionist anthem, “John Brown’s Body.”

“The large edifice was filled to overflowing at this session,” reported the Journal & Tribune, and each and every visitor enjoyed the treat.”

The white press was surprisingly receptive. The Knoxville Evening Sentinel remarked that the AAL “contains some of the brainiest colored men in the country, and is destined to do much good for the race.”

The Knoxville convention of the AAL got national press. The Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, and about 100 other white newspapers in between outlined the basic accomplishments of the sessions.

***

The AAL got so much done the first day, they adjourned and decided not to meet formally on the 15th. However, some delegates arrived that day—after others had left—and were disappointed to have no meetings to attend.

The proud Knoxville delegation was prepared to show the delegates around town, especially to Cal Johnson’s farm and racetracks.

Among those still in town to enjoy the tour were T. Thomas Fortune and Ida B. Wells. They crossed the Gay Street Bridge to go see beautiful Dickinson Island, “and there view the beauties of nature,” then to see the famous stock farm of Cal Johnson, “that gentleman having agreed to display all his fine blooded stock to the visitors.” Johnson, who then leased a racetrack near Dickinson Island, was proud of his string of thoroughbred racehorses. Leading the tour was J.G. Patterson, publisher of a local paper, the Negro World.

Some delegates missed the tours, because they had left that morning. One was L.W. Wallace, the AAL’s new treasurer, from Wisconsin, and his departure caused a bit of a stir. At about 8 in the morning, Wallace walked into the old ETV&G depot building—it stood just southwest of the intersection of Gay and Depot—and crossed some racial lines. By one account, he bought a ticket to Milwaukee, went into the white women’s waiting room and sat down. By another account, it was the “gentlemen’s” waiting room. Patrolman William Dinwiddie attempted to escort him to the “colored” waiting room, but Wallace wouldn’t budge, holding onto his chair.

By one account, he was thrown out on the street, and had to watch his train arrive and depart without boarding. By another, he finally agreed to go to the “colored” waiting room.

(A decade later, by the way, Patrolman Dinwiddie was one of two policemen shot and seriously wounded by the Wild West outlaw Harvey Logan, a.k.a. “Kid Curry.”)

Knoxville newspaper writers wrote about the incident from different perspectives. A writer for the Evening Sentinel filed a skeptical article titled “Are They Law-Abiding?” According to that account, Wallace “rather boastingly” remarked, “Why, you do not know who I am and where I am from!”

Another article for that paper, though, described Wallace as “a large, rather fine-looking mulatto, said to be well educated and a fine speaker.”

However, a reporter for the Daily Tribune mocked Wallace’s “impudence” and his “ridiculous amount of airs.”

Later, Fortune had his own story about his own bit of civil disobedience during his Southern adventure. As he recounted it, he caused a stir aboard a train bound for Asheville.

When he tried to venture into a smoking car and took a seat, a brakeman entered and rudely demanded they go into the room for Black people. “It is needless to say that the brakeman received a lecture he had not expected …. But I knew that if I remained in that car, I should be visited by a committee of lynchers as soon as we got a few miles out of Knoxville; I therefore went into a Pullman car, where I intended to go, anyhow.”

That remark some weeks later in New York made its way back to Knoxville, and the Journal & Tribune took umbrage, citing the rarity of lynching in East Tennessee, and that nobody gets lynched here for sitting in the wrong railroad car, or for “sass.” But they acknowledged that he might have been ejected from the train.

***

Wells began her famous anti-lynching campaign about eight months after she spoke in Knoxville—prompted by the murder of some Memphis friends. One of the most famous and effective Black journalists of her era, she is today the most famous attendee of the 1891 convention.

AAL founder J.C. Price lived only two years after the Knoxville conference, falling victim to Bright’s Disease, a now-obscure syndrome, often interpreted as nephritis, curiously fatal to many prominent people of the Victorian era. His death was a blow to his cause. Admirer WEB DuBois described Price’s death as the crisis that vaulted a lesser-known young activist named Booker T. Washington to the forefront.

Only a few weeks before Price’s death, another former AAL officer also died, but under very peculiar circumstances. Once a much-admired young attorney from Ohio, John W. Hargo had lost some of his early friends, who suspected he was involved in something nefarious. He had just been acquitted of larceny in the Knox County Courthouse in September, 1893, when he went missing. A few days later, a man who resembled him was found dead along a K&O railroad track in Anderson County, just north of Clinton. It proved to be Hargo, with a crushed skull. It was assumed that he had fallen from a train. But some suspected suicide. Others suspected murder. No explanation made perfect sense.

Hargo’s funeral was at Logan Temple, in the same big room where, two years earlier, the promising young attorney had been elected national vice-president of the Afro-American League.

Suffering from Price’s absence, the Afro-American League came apart a few months later. And in 1896, the Plessy vs. Ferguson decision, asserting that “separate but equal” segregation was indeed constitutional, buried some of the assumptions and hopes asserted in the Knoxville conference.

But the AAL was revived in spirit in 1898 as the Afro-American Council, which included new leaders like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, as well some who had memories of the Knoxville AAL convention, like T. Thomas Fortune and Ida B. Wells.

Today, the AAL and the AAC are considered dynamic forerunners of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Others lived much longer than Price and Hargo did. Fortune much later became editor of younger Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist paper, The Negro World—a name coincidentally shared with a long-defunct Knoxville paper. He died in 1928.

Wells published booklets about racist violence, including Southern Horrors and The Red Record, and earned the respect of the elderly Frederick Douglass. Not long after the Knoxville convention, Fortune’s New York Age published her scathing essays about lynching. She was a leader in the founding of the NAACP, though she became frustrated with its conservative pace. Like Thomas Fortune, she sometimes found cause to work with the radical Garvey. But Wells also became a prominent Chicago-based women’s suffragist, once even running for the Republican nomination for U.S. Senate from Illinois. She died in 1931, but earned a posthumous Pulitzer Prize citation just last year.

None of them lived to see the realization of the civil-rights goals they articulated at Logan Temple.

The big church remained a monument on its corner of downtown Knoxville for almost 80 years, witnessing many more dramatic events, some religious, some personal, some associated with civil rights.

During Urban Renewal, it was outside of the zone of mass demolition, but in 1958 the city condemned it as a “fire hazard.” It remained in business for a few years, as the church rebuilt about two miles to the east, on Selma Avenue, losing a large portion of its congregation as it did so. The dramatic setting of the summer of 1891 was torn down in 1964.

By Jack Neely, May 2021

Comment

It is really good to have this history out there because it is proof positive that people of color in this city were destined to be second class citizens with little to no voice.

The establishment was and is determined to keep people under a certain in bondage but make sure to use force when it comes time to make their plans come to pass no matter who it hurts.

Why not, because the average citizen in Knoxville is considered to be pawns not a people who have no voice in how our future, the future of our kids or grandkids is shaped.