For over a century, Tennessee has celebrated June 1 as Statehood Day. But why did our original state seal proclaim Feb. 6, 1796? It was something that happened on Gay Street.

Even the tanners and blacksmiths and distillers who didn’t read the Knoxville Gazette could tell something was afoot. There were dozens of strangers in town, men who looked important and preoccupied. They were up to something.

Although Knoxville was the capital of the Southwest Territory, and was on national maps, it was still a tiny, rough-edged village of buildings of log and plank, clustered atop a bluff overlooking the wild river. Quadrupeds—horses, pigs, dogs, cattle—outnumbered its biped citizens.

The older men, some of them veterans of the Revolution, wore three-cornered hats. The younger men, eager to put the fashions of the past behind them, did not. The U.S. silver dollar was new, and most folks had seen one, but in the taverns, shillings were still legal tender.

Most travelers arrived on horseback, or in coaches. Sometimes people arrived by flatboat, but in 1796, the river was primarily a one-way affair. In the streets daily were a few Cherokee traders, and some people of African descent, most of them formally owned by someone else.

Among the white people, few had lived here long. Some were from the Carolinas. Others were from as far north as Massachusetts. Others were from other countries. Still, they had grown accustomed to each other, and could notice strangers.

These new arrivals that January had little in common with each other. Some were barely adults, some over 65. Some were collegiates, even Ivy League alumni; others had hardly had any education at all. Some had traveled abroad; others had never seen the ocean. Some were from the Southern states, but several of them had grown up in Pennsylvania. At least a couple were originally from across the ocean. Still, they all shared a peculiar mission.

***

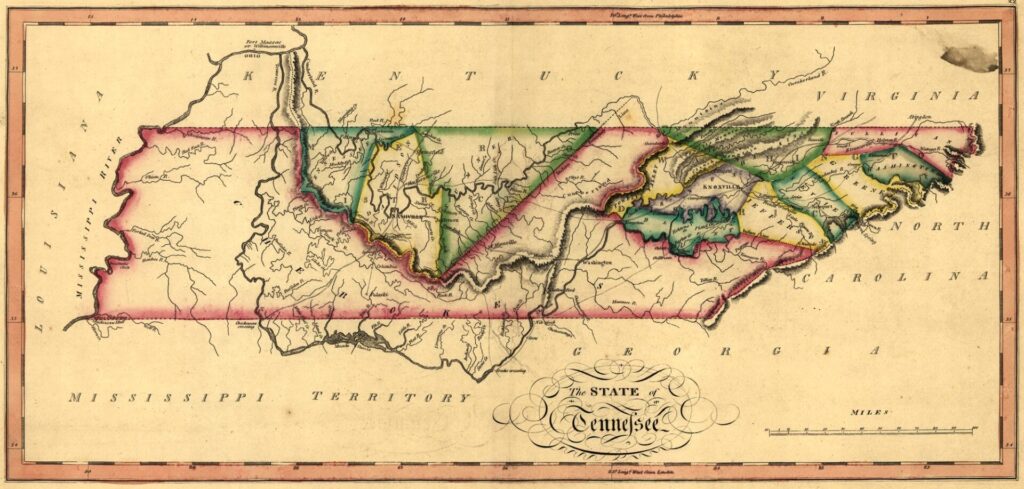

Many Knoxvillians might have recognized the new arrivals, by name if not by face. In 1796, famous people could walk in the streets unnoticed; their images were rarely published. But word does get around. They were delegates from each of the territory’s 11 counties, stretching from the Virginia border to the Mississippi River. These men, 55 of them not counting their aides, had gathered in Knoxville to go about the business of founding a new state.

Nobody gave them permission to do that, except from the settlers who had chosen them to be their delegates.

Among the best known was James Robertson. An eastern Virginia native who now lived in Middle Tennessee, Robertson had been not just a settler, but an explorer, one who had traveled with Daniel Boone. He was a leader of the Watauga Association, the rare experiment with democracy in pre-Revolutionary Upper East Tennessee in 1772. He was now in his 50s; in more recent years, he’d been appointed a brigadier general by President Washington, and had been associated with founding a new settlement on the Cumberland River, called Nashville.

One of Robertson’s companions from Middle Tennessee was a generation younger, a high-tempered young lawyer who wore is red hair in a braid tied with eelskin. Though only 28, he had survived at least one duel and carried scars of a difficult childhood. Son of recent Irish immigrants who both died before he was grown, he bore physical scars on his head and hand, souvenirs of a youthful encounter with a saber-wielding British officer. Andrew Jackson was not yet one of the more famous men gathering in Knoxville that winter, but was one you would notice.

Even younger than Jackson was a delegate from Sullivan County, an Eastern Virginia native named William Charles Cole Claiborne. His age remains a subject of speculation, but some believe he may have been as young as 20–but by 1796 he had already lived in New York and Philadelphia, working as a clerk for US Congress. He was a remarkable young man, and would lead a remarkable life.

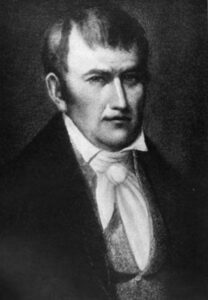

Representing Knox County was the bewigged territorial governor himself, William Blount, who just about eight years earlier had signed the U.S. Constitution, up in Philadelphia along with Franklin, Madison, Hamilton, and Washington, men he knew personally. Perhaps because he knew how it was done, Blount was selected to be president of the Knoxville convention. Also from Knox was original settler James White and Charles McClung, the surveyor from the Philadelphia area who was Blount’s son-in-law.

Some of the delegates had foreign accents. Born in County Londonderry, Ireland, John Rhea was the son of a Presbyterian minister who came to the American colonies when he was a teenager and attended Princeton, but the Revolutionary War interrupted his studies. He joined the Patriots in time for the Battle of King’s Mountain. As a member of North Carolina’s House of Commons, he had helped ratify the U.S. Constitution. But when he arrived in Knoxville, he probably still wielded his Irish brogue.

He wasn’t the only Irishman. Among Knox County’s delegates was John Adair, also from northern Ireland, who was almost 40 when he came to America. Now in his mid-60s and one of the of the oldest delegates, Adair actually had a son who was a Revolutionary veteran.

In his late 30s, Archibald Roane was from Eastern Pennsylvania, a son of Irish immigrants. He was still a teenager when he crossed the Delaware with General Washington and fought at the Battle of Trenton. He taught at progressive Liberty Hall, not long before that college in western Virginia admitted the nation’s first known African American college student.

Joseph Anderson, 38, also from the Philadelphia area, had served as a young soldier with Washington at Valley Forge, and was still with him at Yorktown to accept the British surrender. At the time, he was one of the three supreme judges of the Southwest Territory.

Raised a Quaker in eastern Pennsylvania, Joseph McMinn overlooked his faith’s pacifist teachings long enough to join the Continental Army. He had settled in the wilds of Hawkins County, but was familiar with Knoxville through his service on the territorial legislature.

Born near Richmond, William Cocke had served alongside Jefferson in Virginia’s colonial House of Burgesses. He’d been a leader of the premature movement to found a state called Franklin.

Daniel Smith, from Northern Virginia, was a surveyor and military man who had fought the Shawnee as a British colonial solder in Lord Dunmore’s War, just before the Revolution. He joined the patriots late in the war, in time for King’s Mountain.

At 65, Maryland native John Tipton was older than most of the delegates, and had been a British official in colonial Virginia, but when the war broke out he sided with the patriots, rising to the rank of colonel in the Continental Army. He represented Washington County in the statehood effort, even though he had been a fierce opponent of the previous abortive State of Franklin movement that several of his fellow delegates in Knoxville had supported. He was also a fierce opponent of John Sevier, whom he had accused of treason. Tipton had known much tragedy; his wife died young, and two of his sons died in battle, one just four years earlier, up north in the Battle of the Wabash, when his regiment was ambushed by a warriors of a Native American confederacy.

Probably never have more frontier leaders gathered in one place for a big event.

It was a dramatic moment all over the Western world. Napoleon Bonaparte, a Corsican about the same age as the youngest delegates to the Knoxville convention, was leading French armies into Austria. Wolfe Tone, exiled leader of the United Irishmen, was in Philadelphia planning a major Irish insurrection against the crown—which would end in tens of thousands of deaths, including his own. Toussaint Louverture, after gaining freedom in a slave revolt, was a self-promoted general who was defying colonial authorities in both Spain and France to free the remaining slaves of Haiti, and secure his military rule of that complicated island.

In Scotland, poet Robert Burns turned 37 during the convention, unaware it would be his last birthday. Ludwig von Beethoven was a 25-year-old musician in Vienna who had gotten a little attention from nobles for his piano compositions. Downriver from Knoxville, a disabled but creative Cherokee silversmith about the same age as Beethoven was helping his mother run a trading post along the Little Tennessee. His name was Sequoyah, and he may already have been thinking about creating the first Native American alphabet.

Things were stirring.

***

By the standards of the day, it took 60,000 free men to make a state. A census sponsored by Blount’s territorial government had determined that there were 67,000 free men in the territory, “besides about 15,000 Negroes.” (Women and children apparently weren’t counted at all.)

The delegates met in the commodious office of Col. David Henley, the federal Indian Agent. His job was to keep the peace by dealing with payments and other treaty technicalities concerning the Cherokee. He wasn’t directly involved with the proceedings, but he had a big office, perhaps Knoxville’s only room that could handle 55 men and their aides.

It was on Gay Street, though it was known then as Court Street, because it was the address of the courthouse—at the corner of Church, though considering there had never been a church built in Knoxville, was still called Fifth, because it was the fifth street from the riverfront.

Once they had assembled, Governor Blount called the meeting to order. Samuel Carrick, the Pennsylvania-born Presbyterian who had introduced organized religion to Knox County, gave the invocation. As founder of tiny Blount College—it was decades before it could be called a “university”–he had also introduced higher education to this part of the frontier.

They chose as their secretary William Maclin, another local educator. As clerk, they picked John Sevier, Jr., whose famous father apparently couldn’t make the commitment to attend. (Not exactly Scots-Irish, like several of the delegates, the Seviers were of Franco-Spanish heritage.) The doorkeeper was the fighting Irishman John Rhea.

They agreed on rules. More days than not, including Saturdays, they’d meet usually from 10 in the morning until 3 in the afternoon.

Then, for 27 days, the men argued. A sort of subcommittee of 22—two from each county—was charged with the actual drafting of the constitution. Robertson was chair. The committee included Blount and McClung from Knox, as well as others who would be more famous in years to come, including two of the youngest delegates—Claiborne and Jackson—who were among the quickest with motions and seconds.

Jackson proposed a clause guaranteeing the “right of soil.” It wasn’t an automatic idea in 1796, that a free man who just born in a place would have the right to citizenship. Jackson may have been personally anxious about it; his parents had come from Ireland just before his own birth; his two older brothers were natives of Ireland. It was objected to and voted down, but reframed much more wordily within the context of respect for the U.S. Constitution and other legal traditions, passed.

Some of their concerns may seem surprising today. The Tennessee country was a borderland, between the original colonies and Louisiana, also known as part of New Spain. Under the reign of King Charles IV, Spain had just lost a war with France. Canny politicians on the frontier realized that Spain had been negotiating with its old rival from a point of weakness, and was likely to lose its North American territory to unpredictable, post-Revolutionary France—as it began to, about four years later.

Settlers were anxious about the prospect of crazy France, three years after the Terror and in an aggressive mood, gaining control of the Mississippi River. The delegates included a clause in the Declaration of Rights that “free navigation of the Mississippi is one of the inherent rights of the citizens of this State; it cannot, therefore, be ceded to any prince, potentate, power, person or persons whatever.”

The constitution was to include its own version of the Bill of Rights; Tennessee’s Declaration of Rights would include 32 individual items, not just 10. These men were very much concerned about their own rights, though slavery was unmentioned.

At the time, the African slave trade was over 250 years old. Abolitionism was new, and most often associated with religious movements. In the whole Western Hemisphere, effective anti-slavery policies had emerged only in recent years, in a few states where slavery had hardly caught on to begin with. In 1796, New York and New Jersey were still slave states. The Tennessee constitution made no moved to undermine slavery, quickly or gradually. It references slavery only once, a practical accounting detail in regard to taxation. It appears the subject did not engender any memorable discussion.

However, the document includes no guarantees of the perpetuity of slavery, as some later Southern constitutions would. Nor did it suggest restrictions on the rights of free African American citizens. By avoiding the subject of race, the first Tennessee constitution tacitly permitted free Black men to vote. (We may never know how many did so; in any case, the presumed right was rescinded by that state’s second constitution, executed in Nashville 38 years later.)

The document was unusually liberal in another respect. At the time, across most of America, voters had to be landowners; in many states, that wouldn’t change for decades to come. In Tennessee’s 1796 constitution, landowners had some advantages, in being able to serve on the legislature. But “every free man” who had lived in a given county for at least six months before an election, could vote.

In most states of the New Republic in 1796, one had to be a white property owning man to vote. In Tennessee, all you had to be was a free man. If that wasn’t progressive, in ignoring women and the enslaved, it was an unusual step.

Their attitudes toward religion resulted in a constitution with mixed signals. By one clause, there would be no religious test for public office. By another, Tennessee’s public servants had to believe in a god of some sort. And clerics were banned from office altogether.

There seems to have been some discussion of the matter of how religious office holders had to be; and the minutes suggest it was one of their most divisive issues. There was agreement that “no person who denies the being of god” (lower case) could hold public office in Tennessee. That would permit Jews, Muslims, and perhaps even agnostics to hold office.

George Doherty of Jefferson County, a veteran of the Battle of King’s Mountain, proposed adding “or the divine authority of the old and new testament,” which would seem to require that Tennessee officeholders be Christian. It failed narrowly—by one vote—with Jackson, Cocke, Claiborne, Robertson, and Knox’s Blount and McClung voting together to delete that line. White, Crawford, and Adair liked it.

These men were not all of one mind; some were political enemies. Considering the different backgrounds of the framers, hardly any two of them are very similar, it would seem the main thing they had in common was that they wanted to found a state that was not under the thumb of the president.

One startling surprise, unhinted at in the Constitution, turns up in the minutes. On Feb. 2, Alexander Outlaw—one of the older delegates, he had helped North Carolina approve the U.S. Constitution—made a motion suggesting that the new United States was just one option for Tennessee. If the constitution drawn up in Knoxville that winter were not accepted by Congress, Outlaw declared, “that we should continue to exist as an independent state.”

That provisional rebellion was seconded by Anderson. There seems to have been some hesitation about that one. In the awkward phrasing of the minutes, it’s unclear whether it was passed in principle or tabled, not to be taken up again. Fortunately, it would remain a moot issue.

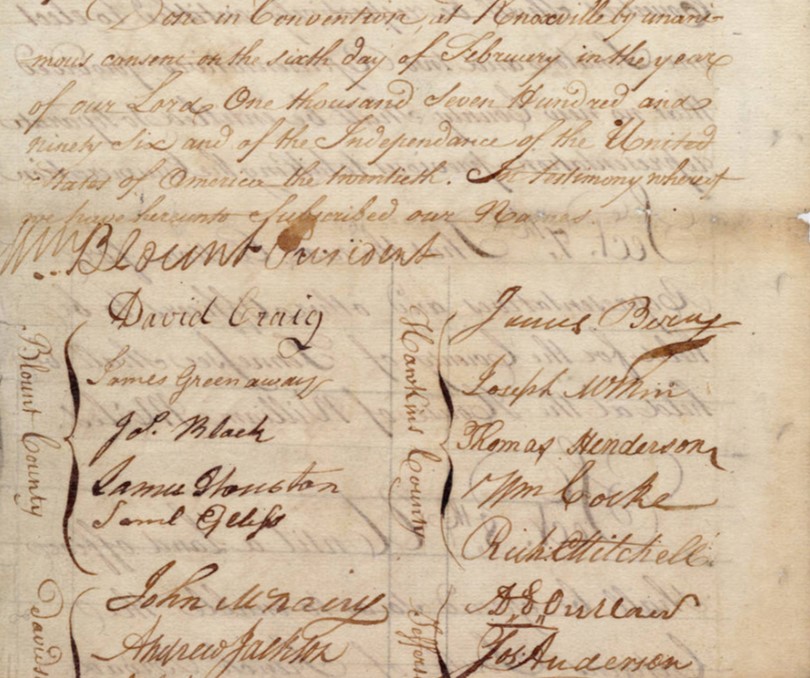

State of Tennessee Constitution signatures including William Blount (Tennessee State Museum/Tennessee Virtual Archive)

On Feb. 6, they all signed the first Tennessee Constitution. Blount signed first, larger than the others. They all had distinctly different signatures. Jackson signed with passionate flair, as if he’d practiced it. Robertson signed just beneath, beneath, an almost meek signature. Some just signed an initial for a first name, but William Charles Cole Claiborne took two lines to sign his whole four-word name. The smallest was the neat, economical signature of Isaac Walton, a delegate from Sumner County.

Blount was given custody of the document, and presumably carried it home to his frame house on Hill Avenue. Three days later, Joseph McMinn carried the document to Philadelphia and the office of U.S. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, who presented it to President Washington and Congress.

There it ran into a bit of trouble.

As far as Tennessee was concerned, it was already a state. Tennessee’s first General Assembly met in the Knoxville courthouse in late March. That month, John Sevier took the oath of office to become Tennessee’s first governor. Perhaps inspired by the egalitarian titles of the French Revolution, he was listed as Citizen John Sevier—a title for which he got a little ribbing in the newspapers of the Northeast–and he gave a short speech expressing his thanks and faith in “our new system of government, so wisely calculated to secure the liberty and advance the happiness and prosperity of our fellow citizens.”

(Seven years later, Sevier would be insulting Constitutional signer and first Congressman Andrew Jackson in the streets of Knoxville, resulting in a challenge to a duel that might have changed history if it had not been awkwardly aborted at the last minute.)

The upstart legislature elected a speaker of the House, and a speaker of the Senate. Then they selected William Blount and William Cocke to be Tennessee’s first two senators.

Several congressmen in Philadelphia raised eyebrows. They weren’t a bit sure Tennessee looked like an actual state. When the question came before U.S. Congress that May–after Tennessee’s first General Assembly had already been meeting for a couple of months–there came several objections, the chief of which was that Congress was supposed to tell people whether it was time for them to start the statehood process.

President Washington offered his opinion that Congress should admit Tennessee, but several congressmen objected, insisting that “before that state could be admitted into the Union, it should first be declared a state by Congress, and the number of its inhabitants ascertained under the direction of Congress; and that it was not sufficient for the state to declare itself entitled.”

Behind the scenes was political anxiety—it was a presidential election year, and Federalists feared adding a state that would likely be dominated by Jeffersonian Democrat-Republicans, especially when Jefferson himself was a candidate.

Supporters of Tennessee countered that “they ought not to be too strict with respect to forms, but admit the citizens of that country to all the rights of freemen.”

When the vote came up in the House of Representatives in May 6, 41 members of the Fourth Congress voted Aye. Thirty Congressmen—over 40 percent of the total–voted Nay. Opposition to Tennessee becoming a state included one South Carolinian and a couple of Marylanders, but seemed concentrated in the Federalist Northeast. Most of the representatives from Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey opposed Tennessee’s admission. Massachusetts and New Hampshire were split down the middle.

In that Congress, one name jumps out. Famous to us because 13 years later, he became president, famous then because he had led the framing of the U.S. Constitution, James Madison of Virginia voted to admit Tennessee.

Another yea vote was North Carolina Congressman Thomas Blount. He was William Blount’s younger brother.

Tennessee had even more trouble in the Senate. William Blount and William Cocke, duly elected as the new state’s first two senators, tried to take their seats before Congress had decided that they lived in a state; they were told to wait outside.

Federalists expressed skepticism of the validity of the territorial census, claiming that statehood should have to wait until a formal U.S. census was taken of the aspiring state. With John Adams presiding–and Aaron Burr of New York a vote in favor of admission–the Senate seemed ready to stall Tennessee until 1800. The House objected, and Congress reached a compromise, to admit Tennessee with two senators–but only one member of the House of Representatives until the formal census of 1800. That would limit the number of electoral college votes for Democrat-Republicans in the upcoming presidential election (which Federalist John Adams won narrowly, by three electoral votes).

They reached the deal on May 31; President Washington signed his approval the next day, June 1. Which, more than a century later, became Statehood Day.

Some Federalist Congressmen had cited issues with Tennessee’s first draft. However, according to early Tennessee historian J.G.M. Ramsey, former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson called the document “the least imperfect and most republican of the state constitutions.”

To be honest, Jefferson had reason to welcome this fresh batch of pro-Jefferson votes. He was running for president the following November. But in calling it the “most republican” constitution, he surely noticed the absence of property qualifications for voters.

June 1 was an important day, sure enough. But letters and diaries make it clear that Tennesseans already considered themselves a state when their 55 representatives signed that document in Knoxville on Feb. 6. For half a century, the full date—Feb. 6, 1796—was emblazoned on the state seal.

***

The signers became even more famous. Tennessee’s first five U.S. senators were all men who had all signed that document in Knoxville on Feb. 6, 1796.

Signer Archibald Roane became Tennessee’s second governor. A county was named for him.

Joseph McMinn would be the fourth governor of Tennessee. There’s a county named for him, too.

Joseph Anderson would spend much of the rest of his career in the new city of Washington as one of Tennessee’s first long-term senators, and also the United States’ first comptroller of the treasury. Anderson County is named for him.

In all, about a dozen counties in Tennessee in 2021 are named for signers of the Knoxville constitution in 1796.

We know what became of Andrew Jackson. It was 19 years later when the world heard of him, first for leading the defeat of the invading British army just south of New Orleans.

By then, W.C.C. Claiborne was already a major figure in New Orleans, as the first English-speaking governor of Louisiana. He’d been one of Tennessee’s first congressmen, then territorial governor of Mississippi, then of Louisiana. He was present at the birth of a second states when he became that state’s first governor. Claiborne is well remembered there with the name of the longest street in New Orleans, Claiborne Avenue.

The defending side of the Battle of New Orleans in Jan. 1815 was a collaboration between two of the youngest signers of the Knoxville constitution, Jackson and W.C.C. Claiborne. Claiborne worked directly with everybody’s favorite pirate, Jean Lafitte.

They both signed that constitution on Saturday, Feb. 6, 1796.

You’d think we’d remember that day.

That heroic generation faded away. William Blount, the president of the convention, died just four years later—enough time to cloud his career with a treasonous international plot that ended his senatorial career prematurely.

In time the event was forgotten. The state capital migrated away from Knoxville and to the middle of the state in 1819.

The Feb. 6 date on the state seal was quietly dropped around 1829, leaving only the year, “1796.” By then, most of the signers were dead. Of course, one had just entered the White House.

Their 1796 constitution was replaced in 1834 by a second constitution. Although it preserved much of the same wording argued over in Knoxville, the second constitution disenfranchised black voters and made the abolition of slavery less likely without something traumatic, like a war.

Meanwhile, Knoxville may have forgotten it, too. One problem was that we had nothing to point to. The city was a practical place, especially in its early decades, when there was almost no public acknowledgement of the city’s early history, and very few landmarks to remind us.

One of Knoxville’s first tourist attractions was an old wooden building on State Street at Cumberland reputed to be Anthony’s Tavern, which by the 1890s bore a sign declaring it “First Capitol of Tennessee.” It probably wasn’t, but it was a very old building. In any case, it was torn down in the 1920s, and is now the site of a parking garage.

Of the approximately 300 buildings and houses that made up the original capital of Tennessee, only one has survived intact in its original location. That’s Blount Mansion, home of the convention’s president. It was saved from a demolition project in 1925; its site was to help with parking for the big new hotel nearby.

In the 1940s, at the time of the sesquicentennial of statehood, historians and librarians met to mark several Knoxville sites associated with statehood, including places where the legislature was believed to have met, between 1796 and 1819—and to try to figure out exactly where the 1796 convention happened.

Historian Laura Luttrell found documents that placed it at the southwest corner of Gay and Church. David Henley’s capacious office had vanished sometime in the 1800s, perhaps even before the Civil War.

In 1947, the Daughters of the American Revolution, in cooperation with the state and other organizations, placed a dark bronze plaque on the Victorian-era Knaffl Building, an old photography studio, declaring it the “Birthplace of Tennessee.”

Three other plaques were placed on three other old buildings, denoting statehood-related sites, as well as a modest marble obelisk on the eastern part of the courthouse lawn, near Sevier’s grave.

Over the years, the buildings where the sesquicentennial plaques were installed with much ceremony were torn down, one less than a decade after it received the honor. The “Birthplace” plaque on Gay Street remained after the others. It became less noticeable after a facade modernization in the 1960s, but was still legible if you knew where to look.

After a 1995 fire, just weeks before the bicentennial of the signing, the Knaffl Building was torn down. At the time of the state bicentennial in 1996—extravagantly celebrated in Nashville–it was a pile of brick rubble. The plaque was saved, but has since been misplaced. It may be somewhere in the City County Building.

Of all the sesquicentennial hoopla of 75 years ago, the only thing remaining to see is the obelisk on the courthouse lawn.

One thing that we haven’t successfully torn down was a graveyard. At First Presbyterian Church are the graves of two of the delegates, including the president, William Blount, and James White, Knoxville’s original settler—as well as that of Samuel Carrick, who was the official chaplain of the event. (Charles McClung would have been buried there, too, like several of his family members, if not for the small matter that he died at a resort in central Kentucky; he was later reinterred at Old Gray.)

Since then, most states don’t get their statehood credentials the way Tennessee did, but the bold gesture became known as “the Tennessee Plan.” It was used again, successfully, in years to come, when Michigan and later Oregon joined the Union. It was discussed, and cited as “the Tennessee Plan,” in the 1950s, as the most desperate option in Alaska. Today, it comes up occasionally among the more radical pro-statehood factions in Puerto Rico.

Today, “the room where it happened” isn’t a room at all. The Birthplace of Tennessee, where 55 men, including Claiborne, Jackson, Blount, and Robertson, worked for 27 days to create a state not exactly like any other, is the corner of the largest surface parking lot on Gay Street. People pay $10 a day to leave their cars there.

Researched and Written by Jack Neely, January 2021

<Click on map to view in detail at the Library of Congress>

2 Comments

Thank you for this wonderful history of Knoxville and the statehood of Tennessee.

Outstanding article.