It might help to go back to a time when Knoxville existed without football. The last time was in the 1880s. Knoxville had a lot of things going for it. Even without any such thing as Tennessee football, the city more than doubled in size that decade. It had a popular annual opera festival, with big stars from Europe and the symphony halls of Boston and New York.

Also new in the ’80s was a handsome public library, well patronized by young people in several new literary societies, like the Irving Club and Ossoli Circle. There were several new factories including, along Second Creek, an industrial-sized brewery. Knoxville in the 1880s was proud of its beer.

And everywhere, in the balmier months, was baseball. In 1879, after an Atlanta tournament, the Knoxville Reds were declared the Champions of the South. Soon every self-respecting business had its own competitive baseball team.

Football was gaining a foothold in the Ivy League colleges and some of the big Northern cities, and was bound to arrive sooner or later.

Football was all around, but Knoxville has a peculiar connection to the original inspiration for American football shared by few football cities in America.

Whether orange-blooded Vol fans want to admit it or not, our interest in football may have come, at least indirectly, from British literature.

If you have your great-grandfather’s books stored away in a trunk somewhere, have a look at the titles. Even if your great-grandfather lived on a farm in Tennessee, as mine did, it’s a pretty good bet that one of his most treasured books was an English novel called Tom Brown’s School Days. It was published under other names, Tom Brown at Rugby, etc.

You might call it the British Tom Sawyer. It’s about an English kid getting acquainted with the ancient Rugby School, a boarding school in England forever remembered for introducing a new sport.

It became an international best-seller, known throughout the English-speaking world, but also translated into French. It first came out in 1857, and was mentioned in Tennessee newspapers even that year. It stayed in print for many years. More than one generation of American boys grew up on it.

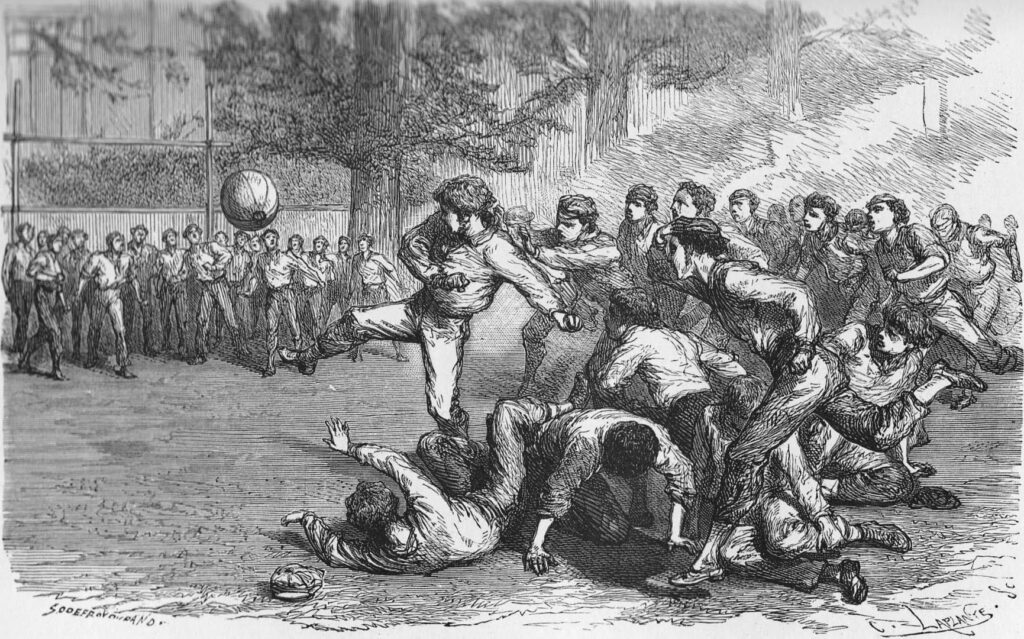

It was popular for several reasons, but the one scene it became famous for Chapter 5: “Rugby and Football,” with its thrilling if a little confusing description of a vigorously chaotic “football match.” Football, then and now, was the very sensible name used by the English for a game later known in America as soccer, which employs mainly the feet. But at the Rugby School, which Hughes attended, they developed an arrogantly eccentric version of the game, in which there was a lot of physical contact, and in which some players, under some circumstances, could kick it through upright goal posts for a score—or even pick up the ball and carry it. The goal posts were described in the book as “gigantic gallows of two poles, 18 feet high, fixed upright in the ground, some 14 feet apart, with a cross bar running from one to the other at the height of 10 feet or thereabouts.” Modern football goal posts are wider than 14 feet, and more forgiving–but the crossbar is still at 10 feet.

At the time, America had no sport anything akin to what Hughes described; our first team sport, baseball, was just beginning to catch on here and there. For many Americans, Tom Brown’s School Days was their first exposure to terms like punt, drop kick, kickoff, goalpost, and offsides (“off your side,” in the novel)–and scrimmage—though Hughes called it scrummage.

It was a complicated game that at first bewildered Tom. “Why, you don’t know the rules; you’ll be a month learning them,” warns his guide, who proceeds to explain the “intricacies of the great science of football.”

The book was well known among literate American boys even before the Civil War. After the war, bored American college kids started playing their own idiosyncratic versions of rugby. In 1869, Princeton played against Rutgers in a game that has been hailed as the birth of American football; but descriptions make it sound very much like rugby. America’s first footballers were the first generation that grew up on Tom Brown’s School Days. That first game was played 12 years after the international publication of Hughes’ book, with the chapter describing it.

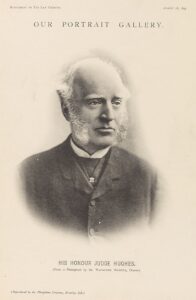

The book’s author had attended the Rugby School in the 1830s, and based much of the narrative on his memories of the place. It was really an autobiographical novel, and the author, Thomas Hughes, was still a young man when he became famous. An abolitionist and Christian Socialist, Hughes was elected to Parliament as a Liberal, and held his seat for about a decade during the Disraeli-Gladstone era.

Like the best of the rich and famous, in middle age Hughes began looking around for something permanent and worthwhile to do with his wealth and influence. The financial panic of 1873 had led to a long depression in Great Britain, leaving many young men–even members of the professional class, and the gentry—without work or resources. Hughes decided he’d find a wild place in America—in Tennessee, no less—and make it a refuge to offer a second chance to out-of-luck economic refugees from England. He secured thousands of acres in the Cumberland Plateau, imagined a town there, and he called it New Rugby, after his favorite school. Eventually it was just Rugby.

It’s hard to buy wild land in Tennessee, because it’s hard to track down the owners. For that, in 1880, Hughes enlisted the help of one of the region’s most able lawyers, Oliver Perry Temple. He was about Hughes’ age, and a writer of some skill, himself.

He was named for Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, who had defeated the Royal Navy in the Battle of Lake Erie during the War of 1812; Hughes didn’t seem to hold that against him.

Temple lived near the university, and was one of its longest-tenured trustees.

In the summer of 1880, word leaked out that the famous Thomas Hughes was interested in some land for an unusual venture. Knoxville invited him to come for a visit. The welcome had a partisan element to it. The Republican Knoxville Daily Chronicle recalled that when many in cotton-dependent England pragmatically sided with the Confederacy, Hughes was a rare British Union sympathizer who “spoke bravely of the motives of those engaged in the defence of the Union. He was our true and faithful friend.”

And 140 years ago this month, he obliged. Hughes arrived on the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia train. The youngest mayor in Knoxville’s history, Mayor Hardy Bryan Branner was only 29 when he escorted the former Member of Parliament, now bald, with muttonchop whiskers, from his train car at Gay and Depot. There were some short speeches, Alderman E.E. McCroskey vowed that Knoxville would extend “an iron arm” to Rugby “that will establish a permanent connection.” Hughes concluded the welcome briefly, conveying “a deserved compliment to our famous and beautiful city among the hills.”

Then they all went to lunch. The three Knoxvillians who joined him in his carriage were three of the city’s most interesting and influential men. One was O.P. Temple. Another was Perez Dickinson, the “merchant prince,” originally of Amherst, Mass., and older cousin of the reclusive and as yet unknown poet Emily Dickinson. Later that day, the party would visit his famous “Island Home” and his elaborate gardens on the south side of the river.

Another in the carriage was Thomas Humes. One of Knoxville’s leading thinkers and authors, he was both a former journalist and a former Episcopal priest. Lately he was president of the University of Tennessee, the first man ever to hold that title, since it was a new name for the old East Tennessee University. He was soon to write The Loyal Mountaineers, perhaps this region’s best account of the Civil War by one who witnessed much of it.

Hughes, Temple, Dickinson, Humes, in the same carriage. Their conversation, guaranteed to be fascinating, is unrecorded.

Their destination was the Cowan mansion on Cumberland Avenue in the neighborhood known as West End. The big house just downhill from the ruins of Fort Sanders was one of Knoxville’s Victorian palaces. A big part of the attraction was the “beautiful and inviting grounds, with a great profusion of shrubs and flowers, dotted here and there with the beautiful water jets spouting and playing around.”

The guests included multiple celebrities, including Knoxville’s first Republican congressman, Horace Maynard—who, almost 20 years earlier, had stubbornly kept representing his Second District in U.S. Congress, even after his state had joined the Confederacy. Later ambassador to Turkey, Maynard was currently in the national position of U.S. Postmaster General. There were several former mayors, including Joseph Jaques, the only Englishman ever elected mayor of Knoxville, and Peter Staub, the Swiss-born theater builder and sometime Swiss consul to the U.S., later U.S. consul to Switzerland, and soon to be re-elected mayor. Earlier in life, he had attempted a utopian resettlement program for Europeans in the Cumberlands. The Swiss colony he called Gruetli had not worked out well, with financial repercussions. Did Staub offer his fellow utopian Hughes any cautionary tales?

They browsed the gardens, then went inside for lunch. In one room, alone on a table in the center, was a copy of Tom Brown’s School Days. There in that place of honor was the book that had surprised America with its description of the exotic game of rugby football.

The Cowans employed an English gardener; his cottage stands at what’s now the corner of 16th and White, and is all that remains of their mansion.

And you may not have to be fanciful in your thinking to at least note that that garden party in 1880 featuring Hughes, was within clear view of UT’s Hill. In fact, it was hardly more than a good punt away from old Wait Field, UT’s first on-campus gridiron.

Before catching a train to the proposed site of Rugby, Tenn., Hughes spent a three-day weekend here, and seemed to enjoy everything he saw. He was, according to one Knoxville journalist, “a true type of the common-sense, plain-mannered and thoroughgoing Englishman of polished, genial, and affable turn, and creates a favorable impression at first sight.”

Is it significant that two of the locals who spent personal time with Hughes, popularizer of rugby football, were fellows both legendary in UT’s leadership? President Humes ultimately had differences with the board and resigned in 1883, just months before the first inkling of an organized football club at the university.

Temple, Hughes’ attorney and closest associate here, was still on UT’s board of trustees when the Vols’ first football program came together in 1891, and was still there later on when they first became competitive.

Of course, football was howling at the gates, and would have gotten in anyway. But did Hughes ever say to Temple, in confidence, “You know, old sport, your charming school should put together a football team, like in my book”?

Maybe the coincidence was inevitable, but within a couple of years of Hughes’ visit, there were rumors of football on the Hill.

In 1883, O.P. Temple’s daughter, Mary, was touring Europe, and made a special visit to see the Rugby School’s “to get a glimpse of the cricket and foot-ball grounds that play so important a part in the interesting account of this place by good Thomas Hughes….” Her letter to her parents didn’t say much more about sports, but was published in the newspaper. (Forty years later, she became the first president of Knoxville’s League of Women Voters.)

Vague memories recorded later say Irish immigrants were playing rugby on a field near the train tracks downtown Knoxville around that time.

In February, 1884, one paragraph in the Daily Chronicle doesn’t say much, but seems to include an obscure joke: “A foot-ball club has been organized on the hill. All cadets [what they called students in those semi-military days] should join this and learn how to kick neatly and beautifully, for there is nothing like knowing how to kick well and to the point.”

The following month, there was a note that one B.F. Blair was a seriously injured playing the game. A year later, there’s a single line that “Lively games of base and foot-ball were played on the lower parade ground yesterday.” It’s likely an early reference to what later became known as Wait Field.

In November, 1885, there’s a note that makes it sound new again: “The latest thing started on the hill is a foot ball club, which was organized a few days ago. And October, 1886, under “Hill Notes,” about the university: “A foot-ball club has been organized, and will soon be ready for business.” What kind of business? The following week, they “adopted a constitution and bylaws.” That sounds prudent. But did they play any games? That information is harder to come by.

By 1887, old-family Knoxvillian Lee McClung became one of America’s first real national football stars, playing for Yale. He remains one of football’s all-time top scorers, and stirred a lot of attention in his hometown for the odd new sport.

In 1889, a most unlikely football pioneer, Japanese student Kin Takahashi, who had picked up the new sport in the San Francisco Bay area, organized a football team at Maryville College.

On December 6, 1890, a non-collegiate Knoxville group got together at the Hattie House hotel downtown—the later site of the Farragut and Hyatt Place—to organize a “Rugby team.” An article in the Journal and Tribune refers to “foot ball” and “rugby” interchangeably. The group did some practicing together, sometimes with the help of Lee McClung himself, home for the holidays. Their first rivals were said to be Mossy Creek (Jefferson City) and Takahashi’s Maryville. It’s not known how often they played.

The UT Vols don’t properly get their start until 1891, when they lost to Sewanee in a single-game season. I don’t know for sure what Hughes thought of America’s somewhat safer and less strenuous version of Rugby football, of whether he ever heard of the team representing his old ally O.P Temple’s favorite university.

Hughes’ death in England in 1896 was mourned there, but also all across America.

The Knoxville Journal & Tribune ran a lengthier tribute to Hughes than it offered to many leading local citizens. “His influence was altogether good and pure, and his memory will be held in tender recollection by millions of men and women on both sides of the water.” Then they yielded to an editorial from the New York Press, which did remark on his influence on America’s rugby-style football–”Thousands of boys have read with delight … of the scrimmage and the great kickoff in the first football match”–while going on to say that Tom Brown’s School Days’ influence was mostly moral, that his first novel had produced a new “vitality” in America, and had shown an unusual positive influence on the whole world.

By that time, Hughes’ experiment at Rugby was not working out as he’d hoped. By the time he died, it might appear that his most enduring legacy in East Tennessee was not going to be a Christian Socialist utopia in the woods.

Dozens of his American obituaries mentioned the memorable “foot-ball match” in his first novel.

Researched and Written by Jack Neely, September 2020

Leave a reply