PANDEMIC:

THE SPANISH FLU: HOW 1918 WAS THE SAME, BUT VERY DIFFERENT

by Jack Neely

These are strange days. You don’t need me to tell you that. What we’re going through now may be “unprecedented” in some ways, as dozens of well-meaning pundits have parroted, in recent weeks.

Before we use that word with confidence, of course, we’ll at least have to consider 1918.

In my youth I knew several people who remembered what happened. Maybe you did, too. None of them are around today. It was the year of what became known as the Spanish Flu. What made it similar to the coronavirus pandemic today is as striking as what made it very different, especially in terms of the public perception of it.

That year, the epidemic was indeed considered newsworthy, but it was never what dominated the front pages. There might be several reasons why that was true.

The newspapers brought violent stories, each day dozens of them, about something else that was unprecedented in scale, the big war in Europe. Both papers, the morning Journal and the evening Sentinel, were full of them. Many of them were optimistic, concerning the “Hohenzollern Proposal,” predicting that Germany was just about to capitulate to the Allied onslaught.

Each daily paper had a Roll of Honor–a list of the American dead and seriously wounded. Despite the optimism, the worst was yet to come. For Knoxvillians in uniform, October, 1918, would be the deadliest month since the Civil War.

But every day that October there was news of something even deadlier than bullets and bombs, and much closer to home.

It’s hard to say exactly when the first Spanish Flu microbe came to town, riding on a human host, but even that almost certainly had something to do with the war.

The army already had hundreds of thousands of men, but needed more. Several hundred young soldiers were training in Knoxville. Some were college kids, forming the Student Army Training Corps, combining military training with a bit of education. Most of them newly arrived in Knoxville, they went to classes up on the Hill at Professor Brown Ayres’ University of Tennessee. It still a small college, almost isolated in its altitude. Most Knoxvillians had never had reason to look at it up close. Football, usually not a big deal anyway, and played at the bottom of the Hill on a non-regulation field that wasn’t altogether flat, was suspended that year for the war. But the soldier-students were working up a nonofficial team.

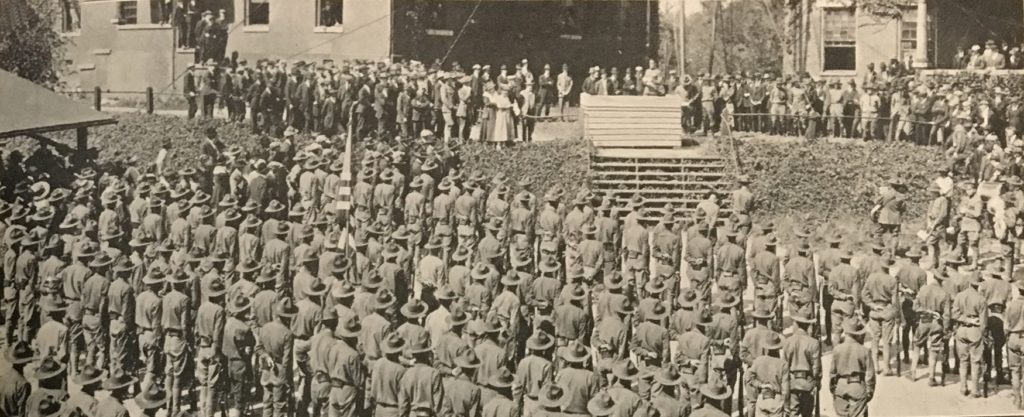

Student Army Training Corps on the Hill at the University of Tennessee. (Cindy and Mark Proteau/KHP)

They’d built barracks up there, and put up an impossibly tall flagpole–100 feet tall, on the old quad behind the antebellum relic called Old College. Every day, that American flag was the highest thing without wings in Knoxville.

The student-soldiers were training on the Hill. Those who weren’t students were sleeping close together on cots in military tents at Chilhowee Park. Some of the training was up at the Rifle Range at Fountain City. It was far away from people who might have been bothered by gunfire.

Knoxville, the industrial city that had grown so fast, was full of people from all over the western world. And it had just completed the biggest annexation in its history; people were now boasting it was a city of 85,000, though that was likely an overestimate.

~~~

Dr. William Robinson Cochrane was 53, a formal, polite fellow “known for his quiet ways and Chesterfieldian manners,” as he was later described. He lived with his wife, Mildred, in a townhouse on Walnut Street, near St. John’s Episcopal. Born in western New York state at the end of the Civil War, he’d been orphaned, and grew up in Pittsburgh, went to Penn, where he got his medical degree. He’d moved to rapidly growing Knoxville in his early 30s, and began his medical practice here.

His son, William Jr., was in the service, a young officer in training in Louisville, Ky. Still at home were his two teenage daughters. He’d been appointed secretary of the city’s Board of Health. It was a part-time job, but it made him Knoxville’s leading medical authority.

In September he and his counterpart, the county physician, had been shrugging off rumors published in Nashville that the aggressive new virus was afoot in Knoxville. The “Spanish Flu,” as it was called, for reasons still puzzling, had been in the news back in the spring, as an unusually virulent affliction mainly affecting Army recruits training in America. It had died out over the summer, but not before catching on in Europe.

By late September, a few soldiers new to town were coughing. Some of them had a fever. Dr. Cochrane was at first dismissive. It’s nothing but the old grippe, he said. “Flu” and “influenza” were relatively new words to most non-medical ears. Most Knoxvillians had grown up with “la grippe,” a term that can still trip people up in old novels. The “grippe” was a bad cold with fever. It didn’t come every year, but older Knoxvillians remembered a siege of it in the early 1890s, maybe three years in a row.

On Sept. 29, Dr. Cochrane said, “Any intelligent physician knows that the Spanish Flu, which has caused so much excitement lately, is a form of la Grippe. Here in Knoxville we have no serious cases reported, and although the number of cases will probably grow for the next week or so, I do not think there is any cause for alarm.”

By the end of that next week, Dr. Cochrane had changed his mind about that. He was one of the first to suspect the worst.

By the second day of October, a few of the military students on the Hill, and a few training soldiers at Chilhowee Park, came down with a cough and fever. It got so bad that the Army assembled a hospital “tent complex” at Chilhowee Park.

Knoxvillians had plenty of experience with deadly epidemics. Smallpox had been around for years, feared but familiar that there was a “Pest House” on the east side of town, in the woods, not far beyond Chilhowee Park. The Pest House was surrounded by graves, not all of them marked. Patients who never got better were buried there. Although more common farther south, yellow fever sometimes visited, necessitating quarantines. Polio was relatively new on the scene. Typhoid was around, off and on. Some elderly Knoxvillians remembered when cholera was a formidable horror.

Maybe that’s another reason why this new flu didn’t dominate the news. It was a familiar old opponent, Fate, in new clothing.

~~~

Knoxville didn’t have an airport or a radio station in 1918. But the city was hardly isolated, with two downtown train stations greeting passengers from all over the country, 24 hours a day, and 14 electric streetcar lines that would take you nearly anywhere you needed to go. There were two lively daily newspapers with competitive staffs. There were six movie theaters, presenting movies starring Mary Pickford, Theda Bera, Fatty Arbuckle, and Will Rogers, several of them released in Hollywood just days before their first showings here. And then there was the Bijou, which presented mostly live vaudeville presented by traveling troupes. Pop music, Hollywood movies, political ideology, and viruses arrived in Knoxville about as quickly as they arrived anywhere.

Flu-era Knoxville was home to several citizens you might have heard of.

Future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Edward Terry Sanford was here then, a 53-year-old federal judge with offices in the Custom House. Beauford Delaney was here, not quite 17 but already known among his acquaintances on predominantly black East Vine as a both comical community jester and a talented painter. Young James Agee was here, a quiet schoolkid in Fort Sanders most people knew as Rufus, almost 9 and living with his widowed mother. Lizzie Crozier French had been working for women’s rights since the 1880s, but in recent years had become more and more outspoken, especially on the subject of Suffrage. At 67, she seemed to be getting only more energetic; her occasional columns, signed “LCF”–everybody knew who that was–competed with war news for space. Bertha Roth Walburn was a violinist originally from Cincinnati, a divorcee of 36 who taught music and was creating ever-bigger symphonic groups to play mostly in hotel lobbies. Carl Martin was a 13-year-old violinist with a very different style from Mme. Walburn’s. He his older brother “Blind Roland” Martin could play nearly anything. Twenty years later, Carl would be a well-known sideman in Chicago.

Col. David Chapman was a pharmaceutical executive of 42, with an office on Gay Street, but he was also a Spanish-American War veteran then helping to train troops at the firing range up in Fountain City. He already had a love for the rarely visited Smoky Mountains; a decade later, he’d be famous for his efforts to do something special with them.

That month Knoxville greeted some notable visitors as well.

The Right Reverend Charles Gore, Bishop of Oxford, England, one of the most prominent Episcopalians in the world, was at Staub’s Theatre on Oct. 4, speaking on the “Moral Aims of the War.” The former chaplain to Queen Victoria was staying with Tyson family at their prominent house just west of UT’s Hill.

McCormick and Winehill, advertised as “the New Jazz Boys from Dixie,” were at the Bijou, part of a show headlined “For the Ladies.” Jazz was a new word to American ears in 1918, and the music didn’t make any sense to many people over 30, but it was what the youngsters liked.

On the same bill was a short drama acted by Charles Middleton and his wife, Leora Spellmeyer, in a romantic comedy. That fact might surprise a later generation. The dark, dour, sharp-featured Middleton later made a career in Hollywood playing sinister villains. Twenty years after his three-night turn at the Bijou, children squirmed in Gay Street matinees when the same actor appeared on screen. Charles Middleton was Ming the Merciless, arch-nemesis of Flash Gordon.

He was one of the last to perform on the Bijou’s stage before the theater closed for several weeks, as the city faced an emergency.

~~~

Knoxville had plans to host two big parties that month. One was the East Tennessee Division Fair — later to be better known as the Tennessee Valley Fair — at Chilhowee Park, where most of the palatial white buildings of the Exposition era, half a decade earlier, were still standing.

The Fair was to be bigger and better than ever, with horse races, and special days for students and soldiers. Knoxville was a city distinctly proud of itself.

To greet a new era at Chilhowee Park were the Hawaiian Serenaders. The fresh Hawaiian-music craze had already brought us droll novelties like the ukulele and the steel guitar, and in years to come would have surprising influence on the development of popular “country” music. Also on the bill were the Ferris Wheel Girls and the accordion act the Bergquist Brothers. Also performing as a 100-voice local ensemble, the Negro Jubilee Singers. Another, the Old Time East Tennessee Fiddlers, was probably a version of the fiddling convention central to annual attractions on Market Square. There was something for everybody. Professor Breed’s Society Horse Show was there, and Margaret Stanton, America’s Champion Lady High Diver, and Happy Jack, the 739-pound man.

But for some, the fair’s biggest attraction was a strange creature a farmer had captured near Beaver Creek. It was a monkey-faced bird that ate rats. No one had ever seen anything like it. Knoxville was a wonderful place.

Also at Chilhowee Park was a tent city of Army recruits, training there before deployment in Europe. By the time the Fair opened, infirmary there was already crowded with young men coughing.

The city’s other big event that month opened downtown, right on Gay Street, a few days after the fair did. The Liberty Bond Drive was a war-effort funding event, with several visiting national show-business celebrities.

~~~

Medical advice in 1918 was, on the one hand, very similar to what we hear today. Cleanliness was paramount, they urged. Wash your face and hands and clothes frequently. Stay away from people in general. If you’re sick, go to bed, and stay there.

But there were also remnants of 19th-century cures. Eating sulfur was supposed to help. Taking quinine–many had gotten used to that after relatives came home from working on the Panama Canal with malaria. Actually, both of those kill germs, and maybe aren’t as weird as they seem. The relevance of castor oil, also recommended by some doctors, is less obvious.

Along with those prescriptions came a charming faith in the power of fresh air and sunshine. Dr. Cochrane ordered that the public streetcars be open to the wind, regardless of the weather. “The only thing for people to do is to get as much fresh air as they can, and go on attending to their own business.”

And it was understood that whiskey was good for anything, especially anything that resembled a chest cold. Even people who didn’t drink believed that a swig of whiskey was as good a treatment for the flu as anything. It certainly felt that way. The problem, of course, was that Tennessee was in full prohibition, a bit ahead of the nation, and whiskey was illegal. That October, several moonshiners, upon being raided, protested they were merely answering the demand for medicine for the Spanish Flu.

By Oct. 5, still in the first week of the first acknowledgement that the flu was on the loose in Knoxville, there were 350 known cases. Dr. Cochrane remarked on an unsettling surprise, that this flu was hitting young adults harder than others, especially those aged 16 to 40.

“How it came to have the name of Spanish Flu, I have not been able to learn,” admitted Dr. Cochrane. And people still argue about that today. It was first assumed to have originated in Europe, but another theory credits that it started in Kansas, where it was first described in America. Recent ideas ascribe its origins, vaguely, to Vietnam or somewhere else in Asia. Spain did have a siege of it, though, and young King Alphonso XIII was one of the first famous people to be seriously ill with it. So it was, to most folks, the Spanish Flu.

UT’s campus, dominated by soldiers, was the first part of town to get strict about it. On the Hill were a reported 70 cases, mainly in the soldiers’ barracks, While Knoxville went about its business, the Hill became a virtual quarantine under something like martial law, with sentries at each entrance. Students were allowed to leave only if necessary. Visitors were allowed to enter only on business, and had to show some proof.

In the first seven days after the first suspected cases, there were only two or three reported deaths, the first of them reportedly a soldier at the medical tent compound in Chilhowee Park. Cochrane was realistic. “We may look for more deaths in the next two weeks,” he said. He was all too accurate about that. He was, by then, beginning to formulate more draconian measures.

The Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) Welfare House at Chilhowee Park supported the troops stationed there. (Cindy & Mark Proteau/KHP)

So many switchboard operators with Cumberland Telephone and Telegraph fell ill that the company asked Knoxvillians not to use their phones except in emergencies. Some mail carriers were sick, too. By then it was hard to deny it was getting serious.

Knoxvillians didn’t know it yet, but Tuesday, Oct. 8, a day when many Knoxvillians stopped believing this was just another episode of “la Grippe,” was an extraordinary day for local soldiers in Europe and their families. Twenty Knoxville boys died in the trenches that day. For Knoxvillians in uniform, it was the deadliest day since the Civil War. Their families would learn about it later. Among the losses Knoxville would learn about, as the epidemic was getting worse, was that of Lt. McGhee Tyson, the handsome young heir and freshly minted Navy pilot. Before his plane went down in the North Sea in the war’s final month, he was best known as a champion golfer.

It was on Wednesday, Oct. 9–as of midnight–that Dr. Cochrane declared “All public meetings, except those of war purposes, will be forbidden until further notice.”

“The closing order will affect any public gathering of any kind,” he insisted. “No one need think that they can hold any public meetings in Knoxville, because any gathering for any non-essential purpose will not be tolerated.”

~~~

It sounds drastic. But there would be one perhaps fateful exception.

And it’s remarkable, reading newspapers of a city facing a deadly epidemic, that it wasn’t a bigger deal in terms of press coverage. There was news of the flu daily, but mainly back on Page 5 or Page 7. Part of the difference between 1918 and 2020, of course, was that it wasn’t the only deadly epidemic in memory. In fact, even if it was several times deadlier than garden-variety influenza, it wasn’t as deadly, once you got it, as smallpox or yellow fever. Of course, they never spread this fast.

Another big difference was the distraction of war. Not just the news of death and devastation in Europe, as America’s ancestral homelands were fighting for their lives, with the help of American lives. But the home front had been directed at that war for 18 months, bringing major shortages of energy and food. There were fewer sports, of course, because there were fewer young men to play them, and fewer young men to ask young women for a night out to the theaters and dance halls. People were staying home more than usual, anyway, or working making bandages and other war supplies for the Red Cross’s efforts. Purely for the war effort, stores were already closing early, and there was an informal ban on driving cars on “gasless Sunday,” to save gasoline for the troops in Europe. Even before the first wandering microbe crossed into the city limits, Knoxville already had a sort of quarantine-like dome over it.

It’s also remarkable that the name of the mayor, John McMillan, didn’t come up much. Neither did the name of Gov. Thomas Rye, or President Woodrow Wilson. They were just politicians, and by the standards of 1918, this was none of their business. Doctors and nurses were in charge now. The Knoxville Board of Health had authority in emergencies to make the rules, as they had been in other epidemics in living memory, in consultation with the Red Cross and Knoxville General Hospital.

Dr. Cochrane recommended closing “non-essential places of amusement,” including schools, churches, pool rooms–there were 25 of those–dance halls, fraternal lodges, and all six of the city’s movie theaters–as well as the Bijou, then the city’s main live-performance venue. (By 1918, the older, larger Staub’s Theatre was showing mostly movies.)

At least 100 people, half of them pool hall attendants, lost their jobs. The “picture show” ban brought particular regrets. D.W. Griffith’s much-advertised two-hour epic about the war, Hearts of the World, starring Lillian Gish, was set to open at Staub’s Theatre the day after the ban. Extremely popular across the nation, it was criticized even at the time for its extreme demonization of German brutality, and, in some cities, subject to censorship.

To see it, Knoxville would have to wait until the virus was done with us.

Most businesses stayed open. There’s no mention of stores or restaurants closing.

~~~

The Fair opened on Oct. 7. It may have seemed a little awkward that most of the city’s known flu patients were the soldiers quarantined in canvas tents at Chilhowee Park at the same time the same park was hosting a regional fair. They went on with it anyway: the Hawaiian Serenaders, the Bergquist Brothers, the Negro Jubilee Singers, the Old Time East Tennessee Fiddlers, and the weird monkey-faced rat-eating bird from Beaver Creek.

Cochrane’s order came down on Wednesday, Oct. 9, which had been announced as Rotary Day, closing the Fair after three days. The Fair’s directors expressed “consternation” about it–this was to be a next-level fair, and they’d gone all out.

But they complied. “Rosy faced, optimistic James G. Sterchi,” the furniture company magnate and president of the Fair, turned uncustomarily grim as he got the news.

Canceled altogether were the special days for schoolchildren and for soldiers. The Fair organization lost tens of thousands of dollars that year, a major setback and enough to raise questions about whether they’d have the resources to launch a fair in 1919. They did go forward, but it took eight years to pay for the 1918 losses.

~~~

To Dr. Cochrane’s ban, there would be one remarkable exception. At a time when Knoxville had more than 1,000 known victims of the flu, the city allowed one event to go ahead. Dr. Cochrane had made an exception for “patriotic” events, and there was nothing more patriotic than the big Liberty Bond Drive, long anticipated and due to open on Oct. 10.

It had been planned to be at least partly held indoors, inside the theaters. Due to the ban, it would be outdoors, essentially a street fair. Or, more than that, a Carnival.

“Knoxville will not be amusementless,” went an announcement for it. Downtown would host “a carnival the like of which has never been seen in the city.” It was an attempt “to make Gay Street gay.”

“Every hour of three days” until 9 p.m., three blocks of Gay, from Church to Asylum (now Wall) would offer multiple stages on vaudeville, performing on flatbed trucks. There’d be an acrobatic dancer, a contortionist, musical acts the Chesleigh Girls, Ruth LaMont, and the Clemenso Brothers. The best known of them, the star of the show, was Billy Baskette, the famous Tin Pan Alley singer and songwriter, noted for the wartime hits “Goodbye Broadway, Hello France,” and “I’m Going to Fight My Way Back to Carolina.”

“If you don’t want to miss the time of your life, don’t fail to take yourself to Gay Street,” went one published recommendation. “It will be quite the liveliest, most unique thing of its kind ever staged in Knoxville.”

The unemployed performers in town for the canceled Fair resented the exception, and said so, but they attended, too.

It was memorable, and the lack of other options likely helped make it one of the most popular bond drives ever. Everybody in town was there, rich, poor, black white, crowded together on Gay Street. There were occasional mentions that it would be safer outside than it would have been inside theaters. Not to say that it would have been entirely safe. As the numbers in coming days would suggest, patriotism was no protection from the Spanish Flu.

A black man named Joe Bogle wrote the following poem, published in the Journal and Tribune:

“Listen here, children,” said Deacon Brown,

“There’s something new just struck this town

And it’s among the white and the colored, too

And I think they call it the Spanish Flu.”

They say it starts right in your head:

You begin to sneeze and your eyes turn red.

You then have a tight feeling in your chest,

And you cough at night and you just can’t rest.

Your head feels dizzy when you are on your feet;

You go to your table and you just can’t eat.

And if this ever happens to you,

You can just say you got the Spanish Flu.

Now, I got a brother and his name is John,

And he went to buy a Liberty Bond.

And he stopped to hear the big band play,

Upon the corner of Church and Gay.

But when he heard about the Flu–

It tickled me and would tickle you–

He bought his bond and went away:

Said he’d hear the band some other day.

But just as he got down on Vine,

He began to stagger like he was blind.

And a doctor who was passing by

Said, “What is the matter with this country guy?”

But as soon as he asked John a question or two,

He said, “Good night, you got the Spanish Flu.”

The reference to Vine was to what was then Knoxville’s “Black Broadway,” the economic and cultural center of African-American Knoxville. The poem touched lightly on a truth that everybody knew: deadly viruses spread even at patriotic events.

At the conclusion of the “Carnival,” the city reported 466 new cases of the flu, for a total of 1,501. The next day, there were 324 more, the next day 429, for a total of 2,264–and seven deaths. In the following three weeks, the number infected would quadruple. The number dying would rise much faster.

Perhaps regretting the orgy occasioned by the very successful war-bond drive, on its final day, Dr. Cochrane remarked that he was “very much concerned over the lack of attention on the part of the Knoxville public to the seriousness of the situation, Dr. Cochrane admitted it was “getting worse.” On Monday, Oct. 14, he laid down more stringent rules. Groups of any more than two were banned.

Spitting in the street became an arrestable offense. Sneezing without a handkerchief in public streets would get the attention of the police. It’s not clear whether any got arrested–they probably didn’t want those people in the jail–but Police Chief Ed Haynes said “we will give them lectures on the personal care of one’s nose.” Getting a lecture like that in public might have seemed worse than getting arrested.

~~~

Although many rural communities seem to have been spared, things were bad in every city across the country. Some cities, like Chattanooga, which was near the large Army base Fort Oglethorpe, had a worse time of it. And it was reported that Dr. Cochrane’s own son, Lt. William R. Cochrane, Jr., in training at Louisville, was sick too, reportedly in critical condition with flu-related pneumonia.

Just two weeks after the first publicly acknowledged patient, Knoxville had 3,616 cases of the virus, and 27 reported deaths.

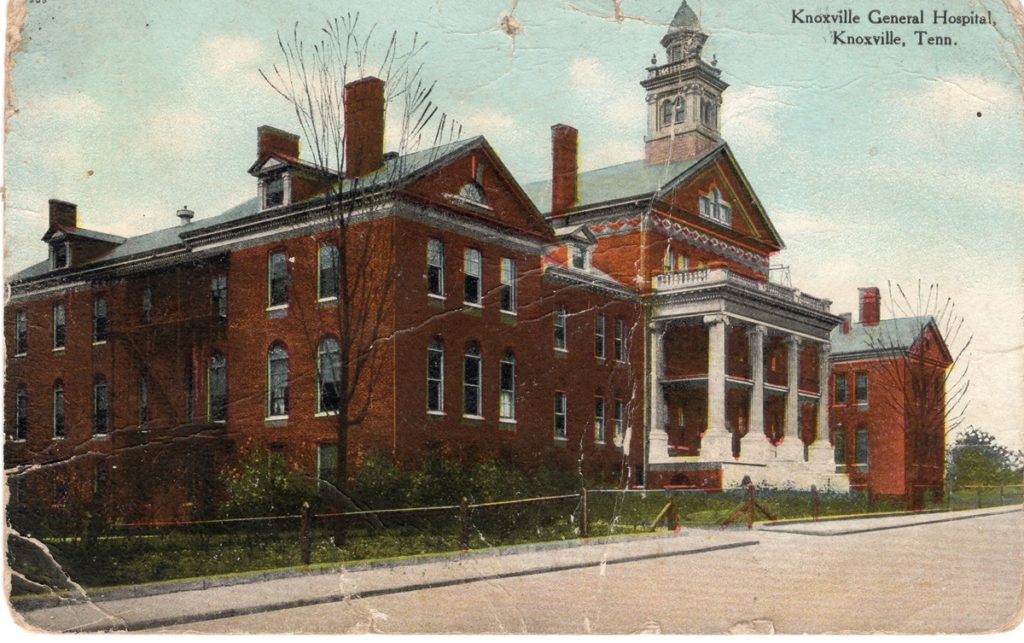

Knoxville General Hospital, the city’s only hospital, located near the cemeteries on the northwestern fringe of downtown, felt the strain. An old medical-school building, freshly renovated as a new nurses’ dormitory, instead became an auxiliary flu ward. KGH announced they could handle 100 flu patients.

Members of the Red Cross Canteen service known as the “Angels of Mercy” on duty at the Southern Station. (Cindy & Mark Proteau/KHP)

It wouldn’t be nearly enough. In the end, there were beds for not quite one percent of the patients.

A 12-year-old girl was apparently stricken with the flu while walking down Gay Street, and fell on the pavement. She was taken to the hospital; what became of her there is unclear.

One unlucky teenage girl named Mabel went to the hospital with a bad flu and seemed to be recovering heroically only to develop a fatal case of appendicitis.

Most people suffered at home, and it’s likely that most of those also died at home. There were horrible stories, one of a whole family of three adults, living out on Lowe’s Ferry Pike–what we later knew as Northshore–dying one by one, the same long weekend.

At another home near downtown, a young mother died hours after watching her five-year-old daughter die.

~~~

Knoxville had once been considered an especially dense city, even by standards of the day. The city had just begun suburbanizing, as symbolized by its recent annexations. But numbers from the era indicate that people who lived in Knoxville proper lived much closer together than we do today, with a density more than twice of what we’re used to.

That density is what made the city seem fun, in descriptions from the era. Even in prohibition, the theaters and poolhalls and dancehalls and cafes, all of them within walking distance of thousands of residents, made Knoxville an exciting place to be, at almost every hour of the day. But density also helped the virus spread. Later state records suggest that relatively few country people got sick.

~~~

As churches remained quiet, the old red-brick courthouse had remained open, its clock tower still tolling the hours, as ever, as if from that height everything were normal, just as it should be. But about two weeks after the theaters closed, Knox County judges chose to postpone criminal trials until there were fewer viruses floating about the marble hallways.

The five-member City Commission kept meeting; the city had several projects going on that had nothing to do with either the war or the flu. Policemen and firemen were due raises; the city had to figure that out. Also, during the deadly weeks, the city took steps toward the most expensive project in its history the Gay Street viaduct, which would carry traffic over the dangerous train tracks, at the expense of lower levels of several buildings on the 100 block, which would be covered by the project’s southern extension. For many people in what were considered “essential” jobs, life didn’t seem to change much.

Carl Roberts, the undertaker, learned that some people were catching the flu at funerals, and endeavored to limit the size of the ones he directed. His own staffers were getting sick.

Knoxville’s significant casket industry, led by the well-known Hall & Donahue Coffin Co., which had a showroom on Gay Street, was getting more business, locally and nationally, than they really wanted, emptying their warehouses of a product much in demand, and unable to fill all orders.

Not quite three weeks into the siege, well-known eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist Dr. C.H. Davis, age 43, came down with the flu. He died at his home on Laurel Avenue.

An 18-year-old man jumped off the Gay Street Bridge, and disappeared into the cool, dark waters below. There was no public speculation about a motive.

By Oct. 21, it was remarked: downtown looked like a “ghost town.” That phrase seems inevitable today, already used frequently to describe downtown in a strange month in 2020. It’s surprising to see it in 1918, when the term was uncommon. According to the Encyclopedia of American Urban History, the phrase “ghost town” became popular in the mid-1920s. Either the unnamed reporter made it up or borrowed it from a recent novel or magazine article about the Wild West.

It was about then, when over 5,000 Knoxvillians had come down with the flu, that Dr. Cochrane–a little eerily considering he had just noted 583 new cases–identified the “crest” of the epidemic.

However he came to that conclusion, he was right. People kept getting sick, people kept dying, but in smaller numbers than in the first three weeks.

On Oct. 29, it was reported that there had been “only” 12 Knoxville deaths from the virus in the previous 24 hours. It seemed a relief.

After about four weeks of his ban, Dr. Cochrane lifted it. The theaters reopened. On Nov. 2, UT’s unofficial Student Army Training Corps football team, likely made up in part of flu survivors, finally played its first game of the season, at bumpy Wait Field, against Sewanee–and lost, 68-0.

By Nov. 7–36 days after the first patient–Knoxville had recorded 8,972 cases of the flu, a figure representing well over 10 percent of the population. The city had suffered 129 deaths from it. By the time they stopped counting, the number of Knoxville cases was topping 10,000, suggesting that about 15 percent of Knoxvillians had been down with the Spanish Flu. Of those, according to the best numbers they had at the time, 135 had died.

Those numbers weren’t complete. A state survey of death certificates several weeks later indicated that 209 Knoxvillians had died of the flu by the end of October, with another 16 who died in Knox County outside of city limits. That was a greater death toll than that of Knoxville soldiers who died in combat in Europe throughout the whole duration of U.S. involvement in that war. Most of them were never mentioned in the newspapers by name.

An informal but convincing end to the epidemic came not then but a week later. On Nov. 11, at 11:00 in the morning, tens of thousands of Knoxvillians converged on Gay Street to celebrate, all together, and close together. It was the Armistice in Europe, and our boys would be coming home.

World War Armistice celebration on Gay Street. The Hope Brothers clock shows 11:00 am on the 11th of November, 1918. (Cindy & Mark Proteau/KHP)

Even the medical authorities endorsed the celebration for a city that had been living under the oppression of several anxieties, viral and otherwise, for months. An impromptu parade charged aimlessly around town. Among its celebrants was a group from the Red Cross and a group of nurses from Knoxville General Hospital, where the worst of the crisis had passed.

Knoxville got it relatively easy. Chattanooga, then a city smaller than Knoxville, suffered about twice as many deaths, likely due to the Fort Oglethorpe factor. Nashville and Memphis each suffered around 1,000 deaths.

Nationally, about two-thirds of a million people died of the Spanish Flu of 1918. They died at all ages, especially young adulthood. Remarkably, the stock market didn’t seem to notice the loss.

A state study the following January questioned the closing of public places, claiming “very little was accomplished” by the bans, and that in some cases it just lengthened the duration of the disease. It’s hard to compare that conclusion to today’s measures for another pandemic. Today, national medical authorities describe the ideal of “flattening the curve,” which may result in it lasting longer, but will reduce demand on hospitals and lifesaving modern equipment like respirators.

Knoxville, like the rest of the nation, had a very sharp curve in the fall of 1918, nothing flat about it. The Spanish Flu spread much faster than coronavirus, in Knoxville certainly, where there were thousands of cases within two weeks of the first diagnosis. Many people got sick, many died, but then it was over. That plan would cause unnecessary death today.

Somehow it never again flared up in numbers that compared to every day in October. More would get sick in the weeks to come, and more would die, even into 1919. But for the most part, it wasn’t big news. Premature death had always been a common thing, and during that spell, it was just more common than usual.

The Spanish Flu’s rampage in Knoxville wasn’t mentioned much after it ended, perhaps crowded out of the public consciousness by the end of the war, the joyous return of the troops a few months later, the League of Nations debates, a couple of violent riots, women’s suffrage, the radio era, the Jazz Age. And the rise of polio.

Some city leaders used the Spanish Flu crisis as proof the city needed more and better medical facilities. People were already talking about building a small hospital at Fort Sanders, near the scant ruins of the Civil War earthworks. But the lesson of the Spanish Flu specifically inspired several locals, including retired saloonkeeper Daniel Dewine, to plan–with considerable help from the international Catholic Church–another hospital, to be called St. Mary’s.

But people don’t really like to talk about viruses. The young soldiers killed in the war were remembered in a memorial book, their names attached to tree plantings and carved into marble and granite monuments. A river bridge and several streets were named for them. Their names are still spoken aloud on Memorial Day. Thanks to the actions of his mother, the name of Lt. McGhee Tyson, who died in the North Sea on a day when dozens died back at home of the flu, some of them even younger than he was, has been the permanent name of an airport for over 90 years.

The victims of the Spanish Flu, arguably indirect victims of the same war, aren’t so well remembered. Nothing is named for any of them. In fact, it takes some research to even find more than a couple of their names.

War monuments are sobering, and can at least give us a moment’s pause. Maybe, like a war monument, a monument to those who suffered and died in epidemics can remind us–because we do tend to forget–that these disasters can happen again, even in our shiny new millennium.

###

11 Comments

Thank you so much. You and Paul do a great job.

Thanks Cindy! Always fun and informative to chat with you. Paul

My grandfather’s first wife died of the Spanish flu in Knoxville at age 36. She left six children.

Excellent history lesson. As we are waiting for our CV surge in a few weeks, I shuddered to read of the mistakes that were made in Knoxville over a century ago.

This is fascinating– what was the name of the family who died on Lowes Ferry?

Hi Tracey,

Thanks for your comment. Do you happen to know the era that the family dies on Lowes Ferry? And do you mean the actual ferry (as in a drowning) or along Lowe’s Ferry Pike? We’ll try to look into it.

Paul

Fabulous accounting of pandemic of 1918 which grandson, TJ Norton III, a young Sevierville attorney shared with me. From earliest memories, I was aware of this deadly Era, My grandmother’s first husband, David Disspayne, died in 1918 and lef us each year to his gravesite in Maryville to decorate his grave. I still make that annual journal.

Growing up, I remember hearing about the Lowe’s Ferry (Northshore) family that died over one weekend. My Scott grandparents both had 1918 Spanish Influenza stories. Thank you for such a well written and informative piece.

Hi Therea

Thanks for your comments and compliments. Do you know the era in which the family died on Northshore/Lowe’s Ferry? We might be able to fin information on that. I’ll ask Jack Neely too to see if he know.

Paul (KHP)

Actually, I realized you referred to Jack Neely’s 1918 story. Here is a copy of the newspaper announcement with the names:

Three members of one family have succumbed within the past week to pneumonia. Cowan Maxwell of Lowe’s Ferry Pike died last Monday after a short illness. A few days later Mrs. Eliza Maxwell, mother of the young man contracted the disease developed pneumonia and died Friday. Saturday morning, R.A. Maxwell, father and husband of the deceased died from the same disease. This is the first instance in Knoxville where influenza has been responsible for three deaths in one family. Knoxville Sentinel, October 19, 1918.

Growing up, I remember hearing about the Lowe’s Ferry (Northshore) family that died over the course of one weekend. My Scott grandparents (Scott/Maxwell/Byerley) made sure we knew that story and others.