You’ve seen the posters all around downtown this winter, a happy, round-faced, exuberant-looking fellow in a black beret. That face might be a nice touch for any city. But Beauford Delaney, the actual person, is the perfect antidote to Knoxville as some of us thought we knew the place.

Fewer and fewer of us are old enough to remember it, and perhaps fewer still will admit it: but there was a long spell when Knoxville had a reputation as a boring, stodgy, lifeless place, parochial, whiter than white, well behaved but unimaginative, hardheaded and practical, and what culture it had was fried in corn meal, with little hint of modern or foreign or fresh.

Of course, that was never strictly accurate. At every point in Knoxville’s past, there were interesting things going on, sometimes barely beneath the surface, green shoots in the broken pavement. But they weren’t often obvious, and the boring-city impression dominated, sometimes carefully cultivated, shared by most visitors and even some lifers alike. Knoxville was regarded with an arched eyebrow, and understood to be a limited concept.

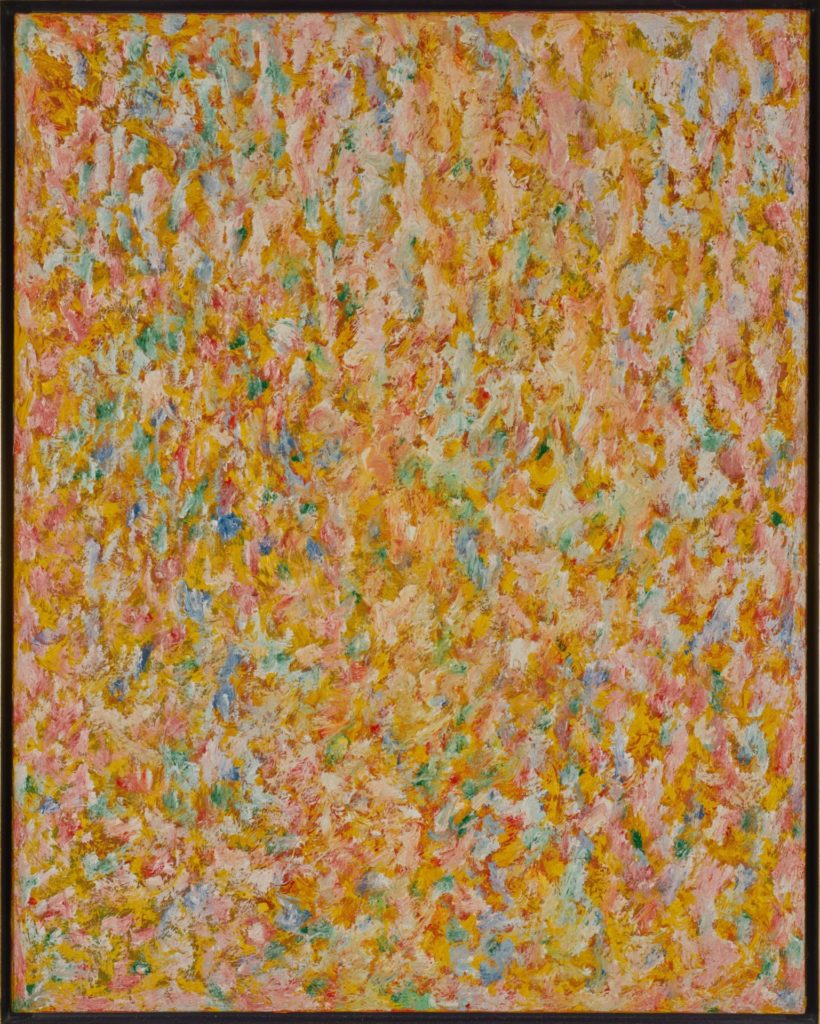

If you were to picture a counter-image to help balance that perception in one person, you could hardly do better than the one named Beauford Delaney. He was black, he was gay, he was unpredictable, he was charismatic. He was an intellectual, and he was an artist, in fact a wildly colorful, creative and unpredictable abstract expressionist. He was cosmopolitan, connected to the world beyond, and adored in Paris and New York, where his paintings, some of them famous and very expensive, have been exhibited, even recently. Somehow, through all that, he was thoroughly Knoxvillian.

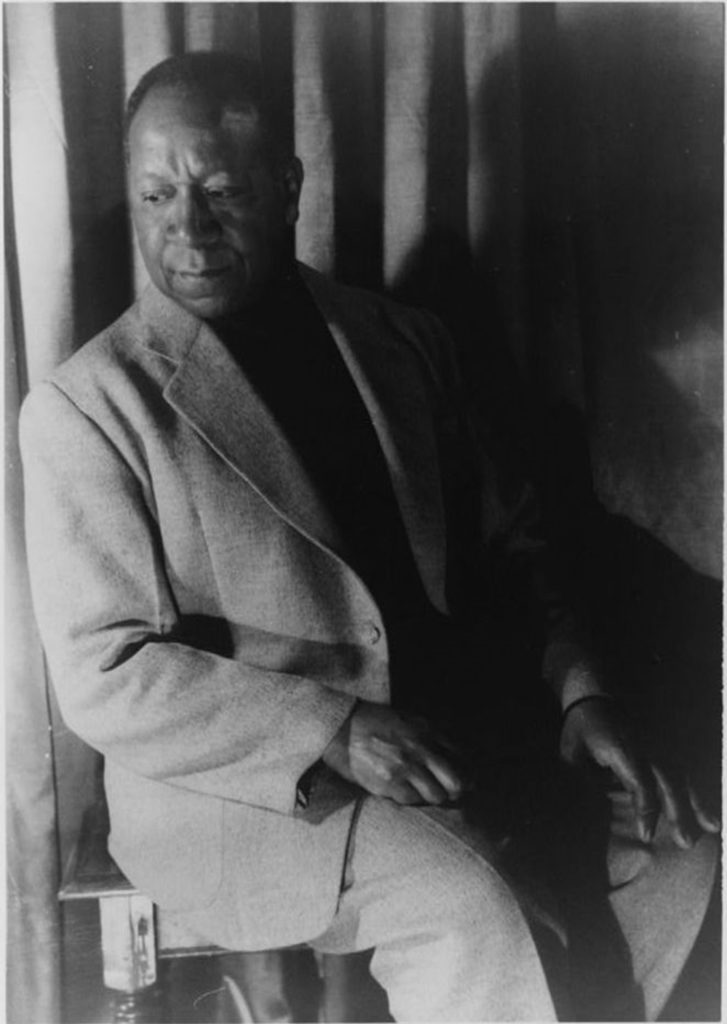

Beauford Delaney, 1952 (courtesy of KMA)

It’s true he moved away when he was not quite 23 and spent two-thirds of his life elsewhere. But he was born here, spent his formative years here, got most of his formal education here, began his artistic career here, was first celebrated here. Although he spent much of his productive life in New York and Paris, he spent more time in Knoxville than did James Agee or William Blount or Howard Baker or Peyton Manning or both Everly Brothers combined. Knoxville was the subject of some of his paintings, and he came back several times in his life just to visit for a while. Even in the artistic capitals of the world, he often missed Knoxville. At the end of his life, his best friend and protege, James Baldwin, thought Knoxville might be the only thing that could save him.

The Knoxville Museum of Art is opening an exhibit about Delaney and his relationship with Baldwin called “Through the Unusual Door.” The painter and the author were closer than friends, not to say lovers. They were mutual counselors, travel companions, allies.

Beauford Delaney was born in Knoxville in late 1901 at his family home at 815 East Vine. The spot was somewhere just east of the Weigel’s on Summit Hill, a spot recently commemorated with a plaque. But it’s nearly impossible to picture East Vine today as it was then, a concentrated community of mostly black-owned residences and businesses, including hotels and drugstores and theaters and dance halls, but with a visible immigrant presence as well. One of the Delaneys’ close neighbors was the original Heska Amuna Synagogue.

Knoxville was technically much smaller, in total city limits population, but before its suburban annexations, the city existed mainly as a concentrated urban area, four times higher in population density than it is today. That’s why perusing its two and sometimes three daily newspapers can make it seem like a bigger city. Every day, everybody was downtown, rich, poor, black, white, immigrant, Baptist, Jew, Catholic. They were all here, and usually found ways to get along and sometimes to be inspired by each other.

One of the Delaneys’ close neighbors was a white-owned business, the Thompson Brothers’ studio; Jim Thompson was becoming Knoxville’s best-known photographer. Five blocks to the south was the home and teaching studio of Robert Lindsay Mason, an artist who had studied with Howard Pyle and Maxfield Parrish, and who was interested in modernist trends on art. I don’t know whether the Thompsons or Mason knew Beauford, but they surely passed each other on the sidewalk.

The young artist saw Knoxville changing rapidly, for the better and for the worse. At the time of his birth, Knoxville saw itself, credibly, as a progressive place with good race relations. There were black doctors and lawyers, black policemen, black representatives on City Council. Toward the end of his time here, the city was becoming something different.

His father, Samuel, was a barber and an itinerant Methodist Episcopal preacher, and in 1905 answered a call almost 30 miles away, in Jefferson City. Although he had occasional positions in other small towns, from southwestern Virginia to Cleveland, Tenn., Rev. Delaney kept their house at 815 East Vine, renting it out, knowing they’d come back someday. Beauford’s mother, Delia, was a creative woman with both quilts and gumbos, and was proud of her talented kids. She was a primary influence on his artistic life. His younger brother, Joe, though different from Beauford in every other way, became an artist, too.

But we can only wonder whether Beauford was here to witness, when he was roughly between the ages of 9 and 12, the biggest public-art events in Knoxville history, the Nicholson Art League’s exhibits at the Fire Arts pavilion at Chilhowee Park, where, during the heyday of American Impressionism, you could see original art by Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam and Robert Henri, major painters of the day.

The Delaneys may have have come back to town to behold some of that. They may have missed it altogether. But they returned to a somewhat different Knoxville in 1915, one in which a radical streamlining of City Council had, deliberately or not, removed black participation in city government.

As if in spite of that, black culture was flowering along Vine Street, where there was a new public library for black readers. The Gem Theatre, at the foot of the hill at First Creek, featured movies and occasional singing stars from the new jazz age. On the same street where the Delaneys lived, there were restaurants and drugstores and pool halls and dance halls and around the corner in 1922, a new public park named for Cal Johnson, the business tycoon, then philanthropist, who’d been born into slavery. Vine Street in the ‘20s became subject of an instrumental piece, “Vine Street Rag,” by Howard Armstrong and Carl Martin of the Tennessee Chocolate Drops. That was Beauford Delaney’s address.

But we also know Beauford witnessed enough of the lynch-mob riot of 1919 to suffer nightmares about it for many years after he left town. He was not quite 18 when it happened. All the machine-gun fire was just down the street from his house. From 815, about seven blocks away from where people were falling bleeding in the street, you could hear every shot.

Beauford was more influenced by another Knoxville, one that vibrated at a different frequency. When he painted Knoxville, it was always a serene place of trees and pools in the sunshine.

He was already talented as a kid. It’s often recalled that he made a remarkably lifelike painting of his high-school principal, who happened to be Charles Cansler, the black intellectual who hosted visits from Booker T. Washington and James Weldon Johnson and WEB DuBois.

He honed his talent through his work with Knoxville’s first professional artist, Lloyd Branson, a popular commercial artist who aspired to be more than that. In 1932, after Branson’s death, Beauford Delaney visited home and described their first encounter. The young artist was at the time working as a cobbler’s apprentice at the Gay Shoe Shop. (It was on the north 400 block, one of those erased by interstate construction.) He dropped out of school after ninth grade and worked learning to repair and clean shoes. The proprietor, J. Robert Willis, seemed to like the kid, and let him draw some when things were slow. Concentrating on his cobbling work, Beauford came to recognize white people by their shoes. One customer, a man who wore white shoes, told Delaney he should meet Lloyd Branson.

Branson was an old man then, but his studio was down the street, on the 600 block, where a few years later, they’d build the Tennessee Theatre. Delaney took the customer’s advice. He entered the dark old brick Victorian building with the old-fashioned gables and climbed three flights of stairs to Branson’s studio where he worked on his famous portraits of Admiral Farragut and Sergeant York and occasionally an impressionist vision of his own. Delaney had met the artist before without knowing it. He recognized Branson by his shoes. They were spattered with paint and turpentine. Delaney had tried to clean them and failed, and felt ashamed about it.

Branson understood. He knew his shoes were uncleanable. The tall, lean artist wore a gray mustache in those days, and a white smock and a crumpled black beret. He was impressed with Delaney, and hired him as a “porter.” There’s a lot of work involved in toting around an elderly artist’s canvases. But while he worked there, he also learned how to mix paints, and Branson gave him a few pointers, things he’d learned the hard way as a mostly self-taught painter since the days just after the Civil War.

In Knoxville, perhaps at Branson’s studio, Delaney worked on some of his first serious paintings. Among the oldest known Beauford Delaney pieces is a watercolor/gouache on paper from 1922, known as “Knoxville Landscape.” It will be on display at the KMA show.

Branson saw a potential in Delaney that surpassed his own abilities to teach, and thought he should go to Boston, America’s leading fine-arts center at the time. He conferred with Hugh Tyler, a younger successful but mostly practical artist, to raise money to send Beauford Delaney to Boston—and with Cansler, who had connections with the intellectual black community. To see him off at the Southern station, Branson wore his fancy spats. It was a big occasion.

In Boston, Delaney visited galleries, attended lectures, went to workshops. He attracted attention everywhere he went. In Boston and in New York where he moved in 1929, everyone seemed fascinated with the short, rotund kid from Knoxville. He had an aura, an unusual energy, a disarming smile, and he had wide interests, attending Italian opera at the Met, and then heading for smoky jazz clubs. At every place, he found subjects for his intuitively colorful approach to painting.

He impressed the people at the Whitney in New York, who hired the young man to work there, and exhibited some of his colorful work. Immediately it led to his first solo show at the New York Public Library. He became well known in art and intellectual circles.

Many people live in big cities and never meet anyone famous, but in his first decade, Beauford Delaney got to know poet Countee Cullen; jazz legends W.C. Handy, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington; singers Ethel Waters and Marian Anderson; author/activist WEB DuBois; poets E.E. Cummings and Elizabeth Bishop; literary giants Malcolm Cowley and Alfred Kazin; photographers Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz; novelists Sinclair Lewis and James Jones; artists Marcel Duchamp, Georgia O’Keefe, and Willem de Kooning; and cartoonist Al Hirschfeld, who of course caricatured Delaney, as he did everybody famous.

Many remarked on Delaney’s almost spiritual magnetism. Perhaps the best short description of Delaney came from the pen of his closest friend, James Baldwin, who called the older artist “a cross between Brer Rabbit and St. Francis of Assisi.”

Today Delaney might be notable to biographers even if he never painted, just for the crazy variety of major creative people he knew. But of course he was an artist, and painted portraits of many of them. He also became especially good friends with Henry Miller, then controversial for his banned “Tropic” novels, who published a long essay, “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney.”

In 1938, he rated a profile in Life magazine that got the attention of the folks back in Knoxville. Popular columnist Bert Vincent remarked on the Beauford Delaney phenomenon. A News-Sentinel feature included a short interview his proud mother at 815 East Vine and remarked of the house where he and his younger brother Joseph were born, “Someday if may be a shrine because it is their birthplace.”

Beauford was much admired in New York, though he never had much money. He sold enough paintings to live on, his friends remarked, but he always gave it away to people he thought needed it more. He was used to being broke, and seemed not to care. He lived in bohemian squalor.

When he had money for a train ticket, he would came home to visit with Delia and the family on East Vine—that is, until he went to Paris in 1953. He had experimented with abstracts before, but there he concentrated on the new genre, developing a reputation even greater than what he had known in New York.

But his life began to come apart. He’d always heard voices; it sometimes seemed part of his intuitive persona. It got worse in Paris, especially as he got older, and he sometimes lost his bearings.

Although his parents were dead, he came back to Knoxville one more time for the Christmas season in 1969-70, to visit with his brother, Samuel Emery, and his wife, Gertrude. He was confused getting here, and at the airport uncertain about whether he could describe how to get to his family home. Fortunately, the cabbie knew the Delaney family, and took him to his brother Samuel’s house on Dandridge Avenue. While he was here, he painted a few more Knoxville-inspired landscapes, with a lot of lush greenery despite the season.

There was an earnest attempt to bring him back later in 1970 for the first Beauford Delaney exhibition in his hometown, at UT’s McClung Museum, but it didn’t work out. He knew about it, though. About three years later, when the 72-year-old Delaney was found confused and wandering the streets of Paris, he was detained and institutionalized by French authorities. Despite the efforts of his friend James Baldwin, who believed the only thing that would help Delaney was a return to his hometown of Knoxville, where his brother Emery lived in a tree-shaded home on a hillside next to the Beck Cultural Center, with a broad restful veranda. overlooking the quiet street.

Of course, that never happened. Delaney died at St. Anne’s Hospital for the Insane in Paris in 1979. In retrospect, there’s been a new appreciation for Delaney’s work. His life was the subject of a 1998 biography by Connecticut scholar David Leeming, called Amazing Grace. His paintings have often sold in the six figures.

Meanwhile, his brother, Joseph, who had spent most of his adult life painting street scenes in New York, moved back to Knoxville in his 80s to accept a post as artist-in-residence at UT. He lived in a cottage near campus and died here in 1991.

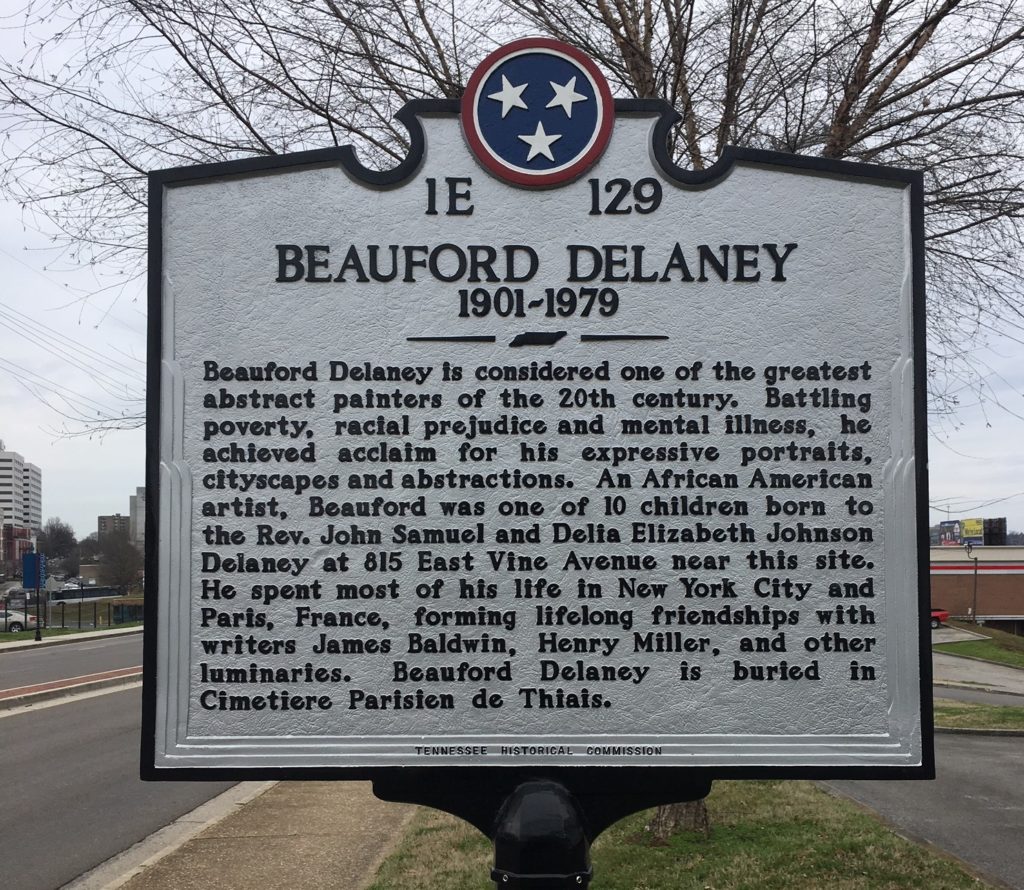

Today, it’s hard to find the home that the News-Sentinel once predicted in 1938 would be a “shrine” to two nationally known artists who were born there. It was demolished in the ‘60s, along with the rest of East Vine, and most of the eastern side of downtown, without any special regard, either from the city or from reporters who’d apparently forgotten about it. But now there’s a historical plaque near it.

Beauford’s parents, Samuel and Delia, are buried at Oddfellow’s Cemetery near Five Points; his brother, Joseph, is at Greenwood.

The Dandridge Avenue home of Beauford’s brother, Samuel, where the artist stayed on his last trip to his hometown, is still there, and is subject of an acquisition and renovation effort through the Beck Cultural Exchange Center next door. The convenience of the setting makes it an obvious target for, if not a shrine, an homage, or gallery, in memory of the artistic Delaneys. (Beck will host a locally produced play based on the Delaney story in late February.)

Fame often has a strange arc. Young phenomena are celebrated with great fanfare. Rarely is a “shrine” suggested for a talented young man in his 30s, black or white, as was the case with Beauford Delaney in his hometown when he was still young.

But after he went to Paris at age 51, and after his mother died a few years later, Beauford Delaney was almost forgotten in his hometown, hardly ever mentioned in local papers. His mental-institution dilemma caught the attention of some wire-service reporters. In 1978, the News-Sentinel ran a New York writer’s appreciation. “Few significant painters have received as little honor over a long lifetime than Beauford Delaney,” wrote Scripps-Howard critic Norman Nadel.

It wasn’t until a dozen years after his death, and a lawsuit concerning his artwork, that younger Knoxvillians heard his name for the first time. Interest has only grown since. He was an interesting fellow. Today we have the plaque at his homesite, some art permanently on display in public places (like KHP’s art wraps), the big show at the KMA, the recent academic symposium at UT, a current exhibit at the History Center, and a play by Marble City Opera debuting at the Beck Center.

And those posters of Beauford in his prime, grinning in his beret, all over the central part of town, are a great touch, a perfect antidote to whatever remains of our old modest expectations of Knoxville.

Beauford Delaney, Scattered Light, 1964 (courtesy of KMA)

4 Comments

Hello I’m a local black business owner that’s actually a barber..!! Lol I’m very touched by this story and would love to have a mural of Mr Delaneys artwork on the building I own.

Hi Wes! We are so glad that this story resonated with you. I would get in touch with the Knoxville Museum of Art as they may have contact info for some local artists looking to do a mural. We hope it works out, as it would be a beautiful addition Knoxville!

I love this essay! I saw Beauford Delaney show in New York and have become somewhat obsessed. You can’t find any prints or books for less than $160.00. In Baldwin’s introduction to his collection of non-fiction “The Price of the Ticket” he writes so lovingly about meeting Delaney as a young man in Greenwich Village. Changed everything.

I love this essay. I dated Beufords Nephew Michael Delaney and got to spend a lot of time in the home on Dandridge Avenue. I even found some of Beuford and Joseph’s paints in the basement and got to use them doing some of my own artwork. I have gotten to see lots of their works in person. so amazing!