In the list of the eight Pulitzer Prizewinners listed as alumni of the University of Tennessee are some who are famous by name even to those who haven’t read their work, like movie-spawning novelist Cormac McCarthy and rock-star biologist E.O. Wilson (neither got a UT degree, but both were students for a short time in the early ’50s, and it’s fun to think of them bumping into each other on the Hill). Also on the list are several bold and hardworking journalists of various stripes.

Headshot from the cover of My First Fifty Years in the Theatre by Owen Davis (1950). (wikipedia.com)

One name stands away from the others. He’s the earliest UT student on that list, and he’s the only playwright. He’s also the most mysterious–mainly because he left little trace that he ever set foot in Tennessee.

His name is Owen Davis. If you’ve never heard of him, you’ve got company. Some writers become more famous after death. Some vanish from collective memory as the ink dries on their obituaries. Although many of his contemporaries are well known, even to high schoolers in 2019–Robert Frost and Jack London were born about the same time–Davis’s name is rarely heard today. Even theater professionals don’t recognize it. But he was arguably America’s most popular playwright during the first half of the 20th century.

His name appears in the News-Sentinel more than 50 times between 1922 and 1945, for his work on Broadway or in Hollywood. One of those articles mentions that he was once a UT student.

That in itself might seem hard to explain. Owen Davis was born on Jan. 29, 1874, in Portland, Maine. He spent most of his childhood in Bangor. All that’s well over 1,000 miles from here.

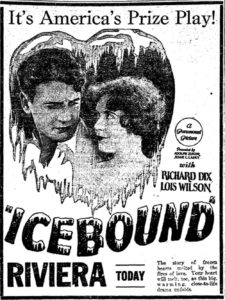

Show ad for Icebound (1924) at the Riveria movie theater on Gay Street. (Knoxville News, April 24, 1924)

The frozen Northeast was the subject of much of Davis’s work, including his most famous play, Icebound, the one that landed him on this list of UT’s Pulitzer laureates. He spent most of his career in New York. He’s believed to have written over 200 scripts, at least 75 of which were produced on Broadway, making him the most prolific playwright of that pre-television era. His plays were produced on Broadway for 37 consecutive seasons.

He also dabbled in Hollywood. He wrote screenplays for some of Will Rogers’ early comedies, and later the iconic melodrama Jezebel, starring Bette Davis, and the play that spawned the urbane comedy, Mr. and Mrs. North, both the 1942 movie and the popular 1950s TV sitcom.

Much of his writing is about New York. So back to our original question. What the hell was he doing here?

~~~~~

Mentions of UT in his official thumbnail bios began appearing at the height of his fame, in the ’30s, when Davis was listed in Who’s Who. They never offer any detail. Just a few words state that he attended UT for one year, 1888-1889, as a “sub-freshman,” perhaps doing prep work for his admission to Harvard.

What brought these Mainers this far south apparently had a lot to do with a new and suddenly famous town called Middlesborough, Kentucky. Today, lacking the original British “-ugh” at the end, it’s a steep-edged small town near Cumberland Gap. But 130 years ago, it was “the Magic City,” a coal-fueled industrial Mecca, the brainchild of Scottish-born industrialist Alexander Arthur.

That city-builder lived in downtown Knoxville then–on West Hill, about two stones’ throws from UT, in fact. Arthur pictured an industrial Utopia in the Cumberlands, a modern city for modern factories. Middlesborough found some traction, at first. It drew capitalists from around the world. One was the elder Owen Warren Davis, the Maine iron manufacturer. He moved to Middlesborough in the late 1880s, bringing his wife and eight children. For his second son, Owen, UT was the closest respectable school, much closer than the University of Kentucky. A railroad between Knoxville and Middlesborough was under construction.

Davis could have left some written memories of UT. The tireless writer was so popular that in 1931, at age 57, he published an autobiography, happily titled, I’d Like to Do It Again. One copy is on the shelves of Hodges Library at UT, a battered old hardback from the first printing, shelved for circulation alongside a few of his plays. It’s a lighthearted narrative, 233 pages long. If he covered each year of his life proportionally, you’d think he’d offer at least four quotable pages about his year at UT. But in a hurry to get to his Broadway successes, he covers his first 15 years in only five pages. “When I was about 15, my father’s business took him to the Cumberland Mountains in the southern part of Kentucky,” Davis wrote, “and he took my mother and the younger children with him, sending my older brother to Massachusetts Tech [MIT] and me to Harvard.”

That one sentence is intended to cover the whole 1888-1889 period when Davis ostensibly attended UT. Without mentioning UT, or Knoxville, or his ever having noticed a state called Tennessee. His description of Harvard is pretty spare, too. He admits, “For some queer reason the memory of the years I spent there is vague and shadowy.”

~~~~~

Many ambitious people, I’ve found, move too fast for their memories. When asked about places, events, and dates even in their own childhood, they get confused, contradictory, forgetful. Maybe we can help Davis out a little by looking at his year at UT from other sources. For both Knoxville and UT, it was a fascinating time of rapid change.

The UT of Davis’s time was a tiny college, a few buildings clustered at the top of the Hill. In 1888, it had been the state university for just nine years. Only 14 when he enrolled, Davis turned 15 on the Hill. He may have already finished high school at Bangor when he arrived. At UT he was termed a “sub-freshman.” That’s just a phrase in biographical capsules; his name doesn’t come up today in databases of UT enrollees. Few records of that era survive. And only one UT building—South College—remains from Davis’s time.

Vintage postcard showing the Hill at the University of Tennessee (Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection)

UT was a practical place at the time, in the early years of Dr. Charles Dabney’s administration, emphasizing agriculture and engineering and the sciences. Ambitious and progressive, Dabney intended to phase out UT’s military-style discipline, but in 1888 students wore uniforms and were called “cadets.” To the dismay of its own faculty, 1880s UT had a reputation as a collegiate sort of reform school, an effective place to straighten out “wayward boys.”

Maybe that fact offers a clue about why Davis chose not to remember.

Dabney also ended the preparatory program for teenagers, and with it, an odd status like “sub-freshman.”

Davis allows that he was fascinated with the new game of football. Later he even did a little coaching on the prep-school level, up north. UT was slow to adopt that northeastern sport, and had no team in 1888. But it’s interesting that that Davis’s academic term here was the very year a few young men started playing with footballs in the Knoxville area. The playwright also tells us he was a champ sprinter; some profs hosted a variety of intramural field competitions, with footraces, some of them held right on the Hilltop quad in early 1889. It would be surprising if the fleet-footed future playwright didn’t join in.

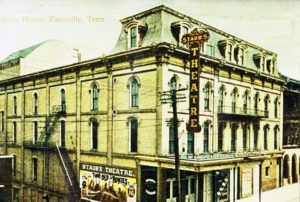

If he learned something relevant to his career here, it may have been off the Hill. UT had no drama program. But just a 10-minute walk up Cumberland Avenue was Gay Street and Staub’s Theatre, with weekly if not daily offerings of contemporary drama by traveling professional companies. It’s perhaps unlikely that a 15-year-old in the custody of a military-style university could have made a habit of the place. But during the 1888-89 season, Staub’s offered a rich diet of light dramas, musicals, and especially comedies–not unlike the fare Davis became famous for in New York. In fact, during the year he was on the Hill, Staub’s presented several of the country’s most popular theatrical performers, many of them well-known in New York. Fanny Janauschek, “the World’s Greatest Tragic Actress” was there that fall, as was Lizzie Evans, “the Little Electric Butterfly”; Ezra Kendall, sometimes called America’s best-paid comedian; New York actress Kate Claxton, so admired she had a town in Georgia named for her; John A. Stevens, actor/playwright performing the title role in his famous mystery, The Unknown; and, remarkably, major operetta composer Victor Herbert, serving as cellist and musical director for a bill that included notable European stars.

Even the legendary Lillie Langtry was at Staub’s in 1888, though probably before Davis’s arrival.

Unless he slipped out or was able to make a matinee, Davis probably didn’t get over to Staub’s very much. Then again, Alexander Arthur, who would have known Davis’s father in Middlesborough, was an enthusiastic supporter of the performing arts at Staub’s, and might have invited the young cadet to come along.

~~~~~

In City Directories, no one in the Davis family is ever listed as a Knoxville resident. However, from 1891 to 1894, the name of O.W. Davis, Owen’s father, shows up in big bold print as executive for a company with a significant presence in Knoxville, the Mingo Mountain Coal and Coke Co. Their Knoxville office was at the corner of Munson (later Bernard) and Wray Street, on the north edge of the National Cemetery. It was a good place for a commodities business, because it was near the railroad that led to Cumberland Gap and Middlesborough.

City Directories don’t list anyone named Davis working in Mingo’s local office. The father of the playwright is listed as the proprietor, but always as a resident of Middlesborough. According to a 1903 capsule biography of the father (when the industrialist was still more famous than his son) Davis was based in Middlesborough from 1889 to 1896.

Some sources claim, again vaguely, that after Harvard (he studied only technical subjects there, and left without a degree) Davis came back to Knoxville after that and worked for a year or so in his father’s business, long enough for him to know it wasn’t his fate. Biographical sources suggest that was ca. 1893-1894. If the future playwright wasn’t a staffer at his father’s Knoxville office, he was surely familiar with it.

His autobiography says he came back south in the summer of 1903–though other biographical sources suggest he was already writing plays in New York at the time, and that his father was no longer in Kentucky.

Davis admitted he was a bad rememberer. But he did recall “working for a coal-mining company with Father. Aside from the fact that the glamourous title of a mining engineer turned out to be just another name for a guy who dug holes in the ground, I simply detested the dirty little southern town in which I found myself.”

Perhaps politely, he declined to mention the town by name. Knoxville was dirty, certainly, with poor sewage and dozens of factories belching coal soot. And ostensibly Southern–if you could overlook the predominance of Republicans. But with a concentrated population of around 25,000, it was hardly a “little town” by the standards of the day, bigger than Davis’s hometown of Bangor. During his time at UT, a delegation of investors from New York visited Knoxville and declared it “the most beautiful city in the South and the most substantial.”

Middlesborough, on the other hand, was never quite the Magic City advertised. It had started with high hopes, but the crash of 1893 all but ruined it. Even its founder, Alexander Arthur, recently a respectable and well-heeled civic leader, left his wife in Knoxville for the fabled gold fields of the Klondike. If Davis was there in 1893 or 1894, Middlesborough was a town in free fall.

But maybe Davis’s “dirty little town” was somewhere else altogether, perhaps one of the little coal-mine towns that popped up and vanished. Mingo Mountain is southwest of Middlesboro, in Tennessee’s Claiborne County, a rugged part of it where towns were sparse.

~~~~~

Most of his plays were crowd-pleasing potboilers, mysteries, silly comedies and tearjerkers, hardly Pulitzer candidates. Just a few, like Icebound, and The Detour, from 1922, drew critical acclaim. A character remarks at the end of The Detour, “New York is full of them, breaking their hearts–painters, musicians, writers, men and women who want to create something and can’t. Wanting to do it doesn’t help much; even trying doesn’t–when it isn’t there!”

Davis obviously had something. He picked it up somewhere.

Unlike most Pulitzer-winning plays, Icebound became a household word, first a radio play broadcast from New York, then a Paramount silent feature, featuring at least one actor from the original Broadway play, earned national release in 1924 and critical praise for its extraordinary realism. “It’s America’s Prize Play!” hailed display ads for its showings at the Riviera Theatre on Gay Street.

Knoxvillians followed his career, whether they knew UT had a claim on him or not. A local article about it didn’t mention Davis’s brush with East Tennessee. In 1929, the Tennessee Players, a UT group, performed their own production of Icebound, at Jefferson Hall. (That academic building on the Hill, known for its auditorium, later burned down.) The director was not a professor, but drama critic Malcolm Miller, the Englishman who became Knoxville’s avatar of the performing arts during that era, as a Knoxville Journal columnist and later manager of the Tennessee Theatre. It was declared “one of the most difficult and ambitious productions attempted by the group.”

It had been 40 years since Davis had left the Hill. But Knoxville and UT had both changed so much during that time it’s hard to assume that anyone remembered him, or that anyone was even aware that he was an alum.

There were more plays, more films. Owen Davis was a Depression-era celebrity, praised by Will Rogers in his popular national column.

Some of his celebrity rubbed off on his son. Owen Davis, Jr., followed his dad into show business, and had a bit of a career as a movie actor. A more photogenic image of his father, he tended to play boyish Americans in war movies and Westerns. He had a role in Knute Rockne, All American, as one of Ronald Reagan’s teammates.

The actor son died before his father did, drowned in a sailing accident off Long Island at age 41.

The last time a Davis play was produced in Knoxville may have been in 1945, when UT’s fledgling theater troupe, U-T Playhouse, produced one act of Davis’s Pulitzer-winning Icebound. Before UT had a theatrical auditorium, it was probably staged at Tyson Junior High.

Davis lived to see his brand of melodrama and light comedy become old-fashioned. He wrote a autobiography with the tongue-in-cheek title of My First Fifty Years in the Theatre, covering his career from 1897 to 1947. (It doesn’t mention UT, either.)

He saw his last production, The Insect Comedy, flop on Broadway in 1948. He died in 1956, at age 82, having outlived the days when he name appeared frequently in New York’s drama columns. The News-Sentinel ran a brief wire-service obit. His name was still recognizable to older folks. It didn’t mention any UT connection.

New York saw one six-month revival of one of his plays, The Nervous Wreck, updated as Whoopee!, in 1979. That appears to be the only time his work has been produced on Broadway in the last 70 years.

The 1924 movie version of Icebound, apparently the only feature film ever made of the play, and hailed at the time as a rare movie that could speak to audiences centuries later, is now considered “lost.”

~Researched and Written by Jack Neely

Leave a reply