By Jack Neely – September 2019

Perhaps like you, I watched the Ken Burns series about Country Music with both interest and trepidation.

As many of us observed almost 30 years ago, Burns told the story of the Civil War without mentioning the word “Knoxville.” A scholar friend did some studying and determined that the Knoxville campaign was the single biggest campaign entirely unmentioned in that long, almost 12-hour series. Well, I thought then, you’ve got to draw the line somewhere. I watched the whole thing three times, and was impressed with it anyway. Though I would have thought the extraordinary story of Parson Brownlow, the slavery advocate turned hardcore civil-rights man, the editor-turned-governor who forced the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments through the legislature thus hastening their passage nationwide, would have slid right in to his dramatic storytelling style.

The Baseball and Jazz series passed with no Knoxville, either. We have colorful and nationally relevant stories about both, but those omissions were less surprising. Same with some of his smaller projects, on Prohibition, etc. Knoxville connects with nearly everything, sometimes in extraordinary ways.

But then came the National Parks series. Surely Knoxville would get its due in that one. Their team did no research in Knoxville, despite the city’s rich and unequaled photographic and video archives on the subject. Writer Dayton Duncan wrote a script, wherever he writes his scripts. Later, his researchers looked around the country for photos and film to illustrate it.

As aired, the Smokies episode seemed creative storytelling on an alternate-universe level. It presented a charming, offbeat, North Carolina-based story, some of which was true, some of which was, to put it politely, very hard to prove–while deftly avoiding Knoxville’s side of the story, which includes a cadre of heroically interesting and influential characters, including pioneer conservationists, some unusual photographers and painters, a former lumber baron, a soldier-pharmacist–and, at the center of the story, Knoxville’s first female elected official. Dauntless, imaginative, hardworking Annie Davis, elected to state legislature in 1925, would have been a great Burns character.

Well, some of us thought. We thought Knoxville’s main contribution to the world was the Smokies National Park. But at least we still have country music.

And here comes Burns with a new series about Country Music. And it was another project in which Burns’s researchers apparently did no primary research in Knoxville–just some clean-up research, looking for film to illustrate Mr. Duncan’s story.

Well, I watched it, and it’s a solid and eloquent narrative. And though I don’t share the Burns-Duncan love for belabored marital and pharmaceutical pathos, I kept coming back for more.

You can indeed tell the story of country music without saying much about Knoxville. It takes some doing, but they proved you could. This time they do mention the word Knoxville more than once–maybe a dozen times in the whole series.

It may be a tonic for some of us who have trafficked in grandiose claims about Knoxville’s claims as the Eden of Country Music. We do get a little carried away about that sometimes.

The city produced some major influences on the American genre, both from natives of its own metro area and the solid boosts the city gave to others who came here from elsewhere just to broadcast on our radio antennae. But calling Knoxville, or East Tennessee, the source of all country music requires ignoring comparable scenes in Charlotte and Atlanta–never mind Chicago–as well as whole realms of influential music coming out of Louisiana and Texas and even California.

And over the years I’ve looked with some frustration for evidence of a real influential Knoxville “scene.” Although several major figures came through Knoxville, most of them did not know each other here. Roy Acuff was long gone from Knoxville before Chet Atkins even arrived as a talented teenager. The Everlys came only after Chet was long gone, and Dolly slipped in after them. Knoxville’s story is a series of really interesting but disconnected episodes. With a few exceptions.

Anyway, I watched the series, and enjoyed most of it. Don’t consider this so much as a critique as a concordance:

– Burns and Co. rather quickly outlines the prehistory of country, choosing to start mostly with the recording and broadcasting era of the 1920s. There’s a lot that could be said about the decades of pre-radio fiddling contests, like the ones we had here on Market Square. That era had its own stars, almost all of them forgotten. And railroad-station buskers like blind Charlie Oaks, whom the late Middle Tennessee State University Professor Charles K. Wolfe, probably the genre’s most esteemed historian, posited may have become the first professional country musician around 1900–when he began selling the lyrics to his songs of tragedy on the street, memorably his song about the 1904 New Market Train Wreck.

Most of the performers Burns did mention have some kind of Knoxville connection, especially those based east of the Mississippi. Most of those connections don’t get mentioned in the film. In most cases, we might be more interested in them than the nation as a whole would be–although in one case, I think they missed a major opportunity to make the series even more compelling.

– Fiddlin’ John Carson, the Georgia juggernaut that Burns presents as sort of the Louis Armstrong of country music, was indeed a major figure who didn’t have much to do with Knoxville, and probably never performed here before 1925–when, already a semi-famous recording artist, he did a series of shows for us at the old Market House. However, some might think it’s interesting his early inspiration and benefactor was our fiddling Governor Bob Taylor, who lived here for a time, and started a group called the Market House Fiddlers. Taylor, who died back in 1912, was an early and effective advocate for country music as early as 1886, when he reputedly engaged in fiddling contests with his own brother, Alf, who was his rival for the office of governor of Tennessee.

– Georgia-born Emmett Miller, the shadowy vaudeville genius mentioned several times in the film, and was a big influence on Hank Williams, who had a radio hit with Miller’s “Lovesick Blues,” never lived here, but performed on Gay Street several times in the ’20s, including at least once at the Bijou. That hardly counts as a footnote, and you might not care much about that if you haven’t read a book by Nick Tosches called Where Dead Voices Gather. It makes you think about those shows, and wonder who might have been in the audience.

– Uncle Dave Macon, the Opry’s first star and arguably Nashville’s, was from Middle Tennessee, and performed in Knoxville several times before and after he was famous. His first records–recorded in New York before the Opry–included one called “Knoxville Blues.” Those were sponsored by Knoxville’s Sterchi Brothers Furniture, in an attempt to get working-class people interested in buying phonographs. I first encountered that fact not from any boastful Knoxville source, but from Professor Wolfe, in Middle Tennessee. I never knew Wolfe, who died 13 years ago, except via a couple of conversations on the telephone, but he wrote a lively book called Tennessee Strings, published by UT Press in 1977, which could pass for a companion volume to the Burns series. It’s an essential business model, to broaden the market for technology by broadening the culture accessible via that technology. We saw a lot more of it through radio, TV, and beyond. Sterchi’s motives seem purer than some.

– Knoxville-based Mac and Bob, the blind duo who were regulars here in the 1920s and made some of those pre-Bristol Sterchi recordings, aren’t mentioned in the narrative, but do appear prominently on a banner displayed in one photograph, representing the scene in Chicago.

– Jimmie Rodgers, one of the major titans of early country music, is one of the stalwart heroes of the narrative, and I admit he may never even have performed in Knoxville. I’ve looked and looked for 20 years, hoping to prove myself wrong. Though he made his first important recordings at Bristol, much of Rodgers’ short career was angled more to the west.

– The original Carter Family, like Rodgers the subject of extensive personal narrative in the series, didn’t travel much together to perform, and spent little time in Knoxville until their second articulation, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters. They actually moved to Knoxville in the late 1940s, in and out of town from about 1947 to 1950, as they performed on WNOX’s live shows. By some accounts, they lived here full time for about a year. It’s hard to nail down musicians, and I don’t know whether the family of five (including future star June, former star Maybelle, and Maybelle’s quiet husband) spent more time at the residential Whittle Springs Hotel–where the Knoxville City Directory for 1950 shows all five of them living, but when other sources say they were already living in Nashville–or in the Chambliss Street area of near-Bearden, where a retired mail carrier once told me they lived. (“I saw June Carter in her skivvies before Johnny Cash ever did,” he told me.) But they became familiar figures here, often performing at humble venues, like the Sears record department on North Central or gas-station openings. In 1949, the Carters helped open the Esso on Kingston Pike at Forest Hills Boulevard. Various members returned many times over the years, sometimes visiting relatives who lived here.

– The show includes only a brief mention of the legendary WNOX radio show “Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round.” The live-audience show lasted for about 26 years. The mention comes from one of the most frequently revisited interviewees, Nashville star Marty Stuart, whose knowledge and personal experience is so vast he becomes one of the prime tellers of the story, is from Mississippi originally, and too young to remember it personally, but had obviously heard of the Knoxville show somewhere, maybe when he was playing with Lester Flatt, and included it in a short list of live-music radio shows around the South.

Contrary to local legend that the Opry copied the Merry-Go-Round, that Knoxville show started broadcasting in 1936, 11 years after the Grand Old Opry–but then again, that was before the Opry was a major national phenomenon, and long before it was in the Ryman. It was started by Lowell Blanchard, the country-music impresario who’d done a country show before that in his native Chicago. Some musicians saw the WNOX show as the Opry with training wheels.

– Their thumbnail about Pee Wee King said that he came down from Milwaukee to make the big time in Nashville. That’s the typical trajectory of mini-bios of country musicians: started here, tried the big time in Nashville. But their lives and travels were rarely simple. In King’s case in between Milwaukee and Nashville, King spent a year in Knoxville honing his performance on WNOX in the mid-1930s. Later on, though, they mention that he first encountered Roy Acuff on Knoxville radio in 1938. They must have known each other here a year or two earlier than that.

– Flatt and Scruggs get their due as the most influential promoters of bluegrass. The narrative outlines their defection from Bill Monroe’s band, and, surprisingly, mentions Earl Scruggs’ early pre-Monroe career in Knoxville. However, it doesn’t mention that after their mutiny, the duo actually moved here to broadcast mostly on WROL where, in 1948, they made their very first commercial recordings. Knoxville was never known as a recording center, but there were several interesting experiments in that regard. Flatt and Scruggs remained here some years, off and on, showing up living at the same address, with their wives, on Rutledge Pike by 1950. Later, they appeared in various early television shows here (unfortunately, surviving film of that era is extremely rare).

But they’re actually a counterexample to the truism that country was born in East Tennessee and moved to Nashville. Neither were from here; Earl was from North Carolina, Lester was from Middle Tennessee. They came to Knoxville just to broadcast.

– The series goes a great deal into the dynamic and influentially genre-blurring career of Chet Atkins, that he was from Union County, that he lived in Georgia in his youth, but without mentioning his first three years at WNOX, when he was a teenager honing his guitar style, rooming with comedian Archie Campbell but inspired by new jazz, and a Django Reinhart record that was being passed around among the musicians at WNOX.

However, the narrative does tell the story of the Carters first connecting with him on WNOX a few years later. I frankly didn’t realize the extent to which the Carters shepherded Atkins to Nashville.

– The story of Hank Williams’ death–which was in either 1952 or 1953, depending on which story you credit–pitches in with the latter, and the idea that he died in his car north of Bristol–although his last serious biographer, Colin Escott, was of the opinion he died in the hotel in Knoxville, or not long afterward. You can’t tell any version of that story without saying that one or more eyewitnesses were lying, so I won’t here.

The startling film of the Andrew Johnson Hotel and the courthouse in the snow comes from our friends at the Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound (it was actually filmed several years earlier). The narrative doesn’t mention the name of the hotel or anything about its history, which was already connected to the end of the career of a very different musician named Sergei Rachmaninoff–but it would have made a Burns-esque touch to mention that the same hotel played a significant role in the early career of Williams’ idol, Roy Acuff.

And by the way, I learned only after it aired that TAMIS also supplied some civil-rights demonstration footage for the film, for context of that era, though few viewers would have seen anything to recognize; I didn’t. One of Burns’ strengths is avoiding cliche by choosing film most people have never seen before.

– Don Gibson is hardly mentioned in the series, but some of his songs, hits for Ray Charles and Patsy Cline, are on the soundtrack. No mention of the perhaps apocryphal story that he wrote “Oh, Lonesome Me,” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You” on the same afternoon in a trailer on Clinton Highway. (I’ve heard that story for 30 years, but never confirmed it. Some have claimed Knoxville’s Arthur Q. Smith wrote those; despite a recent Grammy-nominated box set devoted Smith’s ghostwriter legacy, he’s not mentioned in the series, either.) Still, it seems pretty clear he was living in Knoxville when he wrote his best-known songs, including “Sweet Dreams,” which he wrote backstage at WNOX’s then-new studios at Whittle Springs. From North Carolina, he’s another non-East Tennessean who came to Knoxville to broadcast–and he’s one of the very few country musicians who for a moment, at least, seemed inclined to settle down in Knoxville; he lived not in an apartment or hotel, but in a house in suburban West Hills.

– Dolly Parton gets her due, and she mentions radio and television sponsor Cas Walker’s shows in particular. A lot of the details of her earliest years on Knoxville radio and television are pretty murky and contradictory. She doesn’t remember specifics herself, just that her uncle frequently drove her to downtown Knoxville to perform for welcoming studio audiences–and local evidence of her youthful phenomenon is surprisingly scant. The Burns series says she was on Knoxville television by the time she was 10, which would have been in 1956. Other sources imply she was on radio first, and that it was either earlier or later. Radio logs didn’t keep records of local performers on the air, and newspapers are no help–I haven’t found a single mention of Dolly Parton’s name in Knoxville newspapers before 1966, when she was part of one of those jamboree shows at the Civic Coliseum. If we get left out of books and documentaries, sometimes it’s because we weren’t paying enough attention at the time to give historians something to work with.

The above are less complaints than a bit of extra color for the local audience, things Knoxvillians might be interesting in knowing. But the series single biggest missed opportunity is skipping the extraordinary early story of Roy Acuff.

Burns’ treatment of Roy Acuff’s youth is predictable, and identical to many print treatments. All thumbnail descriptions of Roy, on the air or in print, do more or less the same thing.

He was “born in Maynardville in 1903, 25 miles north of Knoxville,” according to Burns, to a father who was a “good country fiddler.” That’s literally true, but leaves an erroneously simplistic impression of his youth.

At least they did mention Knoxville to help us place Maynardville on the map. The script doesn’t include another mention of the city again until 35 years later. “By 1938, he was on Knoxville radio.”

Roy Acuff on WNOX radio (Courtesy of Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound)

In fact, Acuff spent more than half of that 35 years in Knoxville, playing baseball, learning to play fiddle, learning to sing, getting into serious trouble, getting shot, going to jail, putting a band together, drawing giant crowds, becoming a phenomenon like known ever seen here, becoming Roy Acuff.

Burns shows him in a CHS basketball jersey. CHS was Central High School, in Fountain City, then suburban Knoxville, now within the city limits. Anyone watching the show would assume CHS was some Maynardville team.

They mention he wanted to play baseball for the New York Yankees, but that a heat stroke that nearly killed him ended that dream. That heat stroke, and most of his athletic career, happened in Knoxville. He was rather famous as a local athlete here in the ’20s.

According to his autobiography, the rebellious Acuff learned his fiddle style not from his salt of the earth dad in Maynardville, but from an automobile mechanic in Fountain City.

They left out several of the jolting details of challenge and hardship of a sort the Burns company usually likes to include–like that Roy had been arrested several times, for bootlegging, gambling, and assault. Or that he was actually shot in a bootlegger’s joint called the Green Lantern Tea Room and hospitalized–and the assailant got off on a self-defense plea. Roy, aggressive on the athletic field and off, had a reputation.

It’s easy to imagine Peter Coyote reading Dayton Duncan’s take on all that. Maybe next time.

It doesn’t mention his first band, a trio called the Three Rolling Stones, that played at the Tennessee Theatre in 1932. Nor does it describe what an extraordinary phenomenon Acuff’s later band, the Crazy Tennesseans, were here in town.

A large band of as many as 14 pieces, the Crazy Tennesseans coalesced around 1935, was such a phenomenon it was evicted from the performance space on the roof of the swank Andrew Johnson Hotel, tired of dealing with the hundreds of non-paying customers. They then outgrew their next venue, an old boxing ring. When they arrived at the city-sponsored Market Hall on Market Square, theater owners complained bitterly to the mayor that the Acuff phenomenon was ruining business.

Part of the band’s appeal was that they had something new called a dobro. The Burns narrative doesn’t mention that, and how unusual it was, this exotic Hawaiian-music modification from the West Coast, not a country instrument when Acuff added it to his band, having heard a guy named Clell Summey playing one in a drugstore on Broadway. With their recording, “Great Speckled Bird,” and subsequent performances on the Opry, Acuff’s band introduced the dobro to most of the nation.

That’s a good story, I think. I would have put that in my documentary about country music.

And, as we’ve learned before, Burns researchers are handicapped by the fact they don’t come to Knoxville to do research. I’ve talked to several library directors about the subject, both through our prodigious county system and the University, both of which have some of the region’s best archives in both print and motion-picture and sound recording–and they all seem equally perplexed. Burns’ researchers literally never come here unless they have a specific request for an image they already know about, to illustrate a story that’s already been written, and then they do it by long distance.

It doesn’t do to complain. If Burns and his researchers didn’t come to Knoxville to research the history of the Smoky Mountains or the history of country music, I figure they never will.

Nashville and Bristol both have well-funded institutions set up to promote the story of country music. Maybe Nashville and Bristol don’t tell Knoxville’s stories. We have to tell our own.

If our best stories didn’t make the cut on the Civil War, Smokies, and Country Music series, I’m trying to think what else we have. Maybe that should be our municipal project, the next mayor’s goal. Let’s work up a story so good they can’t ignore it.

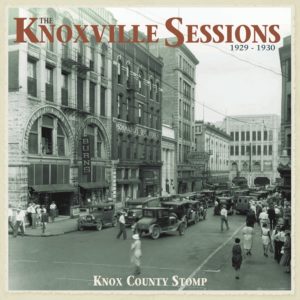

More than 100 recordings made by the national Brunswick-Vocalion label in cooperation with WNOX in 1929 and 1930 at downtown Knoxville’s St. James Hotel included some jazz and blues but also the work of several seminal and influential country-influenced musicians, including Ballard Cross, who contributed one of the earliest recordings of “Wabash Cannonball”; the Tennessee Ramblers, featuring female lead guitarist Willie Seivers; and the Tennessee Chocolate Drops. They were released in a box set by Germany’s Bear Family Records in 2016, and the accompanying book was nominated for a Grammy.

Leave a reply