By Jack Neely – July 2019

Some dramatic days you might almost wish there was some kind of monument to the weather, to the meteorological moments worth remembering. There is, in fact. It’s the elegant old weather kiosk, restored in recent years. It looks like something built for an Exposition of the beaux-arts era. In fact it was originally installed in 1912, not long before Knoxville’s gigantic and elegantly appointed National Conservation Exposition of 1913.

Some dramatic days you might almost wish there was some kind of monument to the weather, to the meteorological moments worth remembering. There is, in fact. It’s the elegant old weather kiosk, restored in recent years. It looks like something built for an Exposition of the beaux-arts era. In fact it was originally installed in 1912, not long before Knoxville’s gigantic and elegantly appointed National Conservation Exposition of 1913.

It’s painted mostly white, and you might guess that it’s made of wood. But punch it with your fist, and you may regret it. It’s made of 3,600 pounds of iron.

It was known, in the early days, as the Kiosk, always capitalized. Sometimes newspapermen referred to it collegially, as Mr. Kiosk.

People used to gather around it, in person, to see what the federal weatherman had observed, and what we could expect next. Checking on the weather was a social event. People would stop by, talk to strangers, say, Boy, it’s hot. So many people hung out around the Kiosk, they earned a nickname: they were the Kiosk Leaners.

Today, the big relic is said to be one of America’s only remnants of the Weather Kiosk Era. It’s a rarity, a landmark. Hardly anyone pauses there except for tourists, trying to figure out what it is.

Today, in its old windows, instead of today’s weather, there’s some interesting historical lore about the East Tennessee Historical Society and the Custom House / History Center. When people do wonder about the weather today, people glance at their phones, which they were glancing at anyway. When it’s very hot, we may complain for a moment. Then we just go inside, where it’s not only cool, but sometimes cold. From home to car to office to car to home, it’s easy to forget about what it’s like outside.

There were days when the Kiosk was the center of Knoxville’s attention. One day like that, 89 years ago this month, it attracted a crowd.

You can’t help but remember when people got hot in style. The phrase “hot enough to fry an egg on the sidewalk” had been going around since early in the century. In 1925, a man named Ulysses P. Evans, who lived on West Fourth, gathered some neighbors in mid-July and made it happen. He reported it took about 10 minutes.

It got up to 101 that year. Five years later, it got a little hotter.

Knoxville had had 100-degree heat only four times in history. The last, in 1925, was 101.5, an all-time record most folks assumed wouldn’t be broken in their lifetimes.

That July day in 1930, a fellow came out to the corner of State and Cumberland in the bright sun, wearing an apron and a chef’s hat, with a spatula and an egg. He cracked his egg not on the dirty pavement but on a hot manhole cover. Maybe that was cheating. But it worked. The white went solid pretty quick. Dozens watched, and a newspaper photographer snapped a shot. Later the man with the spatula said he wasn’t all that hungry, anyway, and left his egg to the masses.

People remembered that week for decades to come.

Knoxville was in the middle of a national heat wave that enveloped the Midwest and the Deep South. It had been hot for days, ever since the Fourth of July. On July 10, it got up to 98. Then cloudy skies and some showers brought it down to a milder high of 84 on Friday. On Saturday, the temperatures started rising early, and kept rising.

In those days the Carter Family often sang about keeping on the sunny side. It wasn’t always good advice. A reporter noted that though thousands of people were shopping downtown that Saturday, the sunny sides of downtown Knoxville’s streets were mostly deserted.

In 1930, air-conditioning was just a little more than a rumor. The Tennessee Theatre, less than two years old, had some acquaintance with it: “Always Cool and Comfortable,” they claimed, without testimonials. Their newspaper advertisements spelled out TENNESSEE with frosty letters.

The movie that evening was A Man from Wyoming, starring Gary Cooper. It wasn’t a western, but a World War romantic drama, set in France. In honor of the heat wave, the News-Sentinel gave away two free tickets every day. Others bought tickets just to cool off.

The new Andrew Johnson Hotel was doing good business. Most of its rooms were far above the hot pavement. Restaurants advertised ice cream. Mr. Armetta’s little ice-cream factory in the Bowery did good business.

Most offices didn’t have air conditioning, and hardly any homes did. People had fans, and iced tea. They made do.

Those who could afford a car drove up to the new Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Roads leading out of Knoxville were noticeably jammed.

City crews drove around strewing sand on the streets. The sun was melting the tar on the asphalt, making it sticky. Cross it on foot, and you might leave a shoe behind.

“Heat from the sidewalk was almost suffocating,” reported the Journal. “Staying indoors was next to impossible, and remaining in the shade gave very little relief. The sun’s heated rays penetrated everything, and very little comfort was to be had.”

In neighborhoods, people were out on their porches and under trees “trying in vain to get relief from the breeze which was not blowing.” And never mind dreams of a weekend nap. “Trying to sleep was useless.”

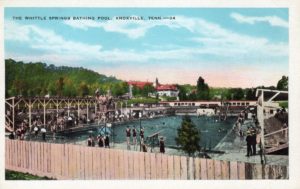

Whittle Springs Pool (Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection)

Whittle Springs’ giant swimming pool registered the most swimmers at one time in its history. Fountain City Lake and Andrew Jackson Lake–its former and future name was Dead Horse Lake–were full of bathers. Some almost completely full. All swimming pools, including the ones at the YMCA and YWCA, were “uncomfortably crowded.” Actual swimming was impossible. Knoxvillians were just standing in any pool that would allow them, cheek to jowl, to stay cool. Or, at least, less hot.

Tennis and croquet courts were abandoned; it was just too damn hot for that sort of thing. Miniature golf courses, the latest fad, were, if not completely deserted, scanty for a Saturday.

It was noticeably hottest downtown. A young girl named Emma collapsed on Market Square, a victim of heat stroke. “Numerous persons swooned in the crowded market district,” reported the Journal. Police reported that farmers seemed to have the hardest time of it—they speculated that was because they were less used to it. They spent more time outside, maybe, they said. But no East Tennessee farm was a hot as downtown Knoxville, where the sun’s heat soaked into the pavement and radiated.

Mrs. Robert Weiss, Halls resident and an officer for the Knox County Republican Women, had plenty to worry about, anyway, considering an already-disastrous Depression suggested a tough re-election campaign for the no-nonsense Republican president. She collapsed in her office at Republican Party headquarters, Market and Cumberland. Doctors said she had a mild heart attack, but she rallied quickly.

The Brownlow Building, just north of Market Square on Wall Avenue. (McClung Historical Collection)

Another familiar local politician, R.L. Scruggs, the middle-aged grocer who had won a close race for City Council a few months before, collapsed in his grocery on Western Avenue, and was prostrate for hours afterward.

Hubert Huff was the youngest weatherman at the U.S. weather station downtown at the old Brownlow Building. Not well-remembered today, the Brownlow was on the old northern section of Market Street, across Wall Avenue from Market Square.

Guys with seniority prefer not to work Saturdays, so Huff was in charge. He wasn’t happy about it. He’d had the flu back in March, and had been sick off and on for months. Today, he had a bad sore throat, and what he called a “cold” on the hottest day; he probably should have called in sick, but the weather doesn’t offer days off. He climbed up the stairs to do his duty. The official weather-gathering station was on the seventh-floor roof of the Brownlow. It was past 100 by lunchtime. By 3:00, it was up to 101.7. Then, for some reason, it plunged to 100. Then it got back up to 101.7, and 101.8 at 4.

Despite the lateness of the day, it kept rising. At 5:45, it hit 103.7.

That number, sometimes rounded to 104, was called the 60-year record, because it had been 60 years since the U.S. Weather Bureau started recording Knoxville’s temperature. It stood as the official record, Knoxville’s hottest day in history, for more than 80 years.

However, that seemed low compared to the heat of the streets. Some pedestrians said it had to be at least 140.

In fact the Kiosk at Market and Clinch recorded a temperature of 112. That was what they called “the street temperature,” recording the radiating heat of Clinch and Market Streets. But it was weather-bureau policy to record it in the shade, on the roof of the Brownlow building. That’s where Huff got that 103.7 reading that left some sufferers feeling short-changed.

A Journal reporter wrote a tongue-in-cheek interview with the already historic monument, which he called John J. Kiosk.

“Some people you know can’t ever figure why I’m always saying that it’s hotter than the weatherman says,” Mr. Kiosk was quoted. “Well, the weatherman, he’s got all them funny contraptions of his up there on a roof. And here I am standing down here on the sidewalk. The sun begins to bear down and throw that heat up in my face, and I reflect it. Now don’t you talk to me about the weather. I’ve been in this business a long time, and when I say it’s so hot, it’s so hot, and don’t you nor nobody else say different.”

Then, the reporter remarked, “Mr. Kiosk bristled, harrumphed, and sort of shifted his weight from one foot to another.” Then he offered an almost Taoist philosophy. “My rules for success are very simple. Live a quiet life, never get excited about anything, always be where people can find you, and be ready to tell them what they want to know.”

Welcome showers that Sunday brought it all the way down to 71, almost chilly compared to the Saturday no one forgot.

~~~

Meanwhile, changes were already afoot for the Kiosk. There were plans for a new post office, a grand, neo-classically modern place, with pools out front and a promenade. Or maybe just an expansion of the old Custom House site, to take up the whole block. Or, as turned out to be the case, moving it to an impressive new marble building on Main Street.

It came to pass, though, that after the Kiosk’s moment at the center of sweltering Knoxville’s attention, federal officials decided a permanent Weather Station was no longer necessary. Technology had outmoded it. Everybody had radios now. Knoxville had three radio stations, and they reported the weather. And the Kiosk’s grandly decorative style was way out of fashion in the Moderne ‘30s.

Soon after the hottest day, it leaked out that the Kiosk would be decommissioned, perhaps moved to be used for some other purpose, or discarded for scrap.

But Knoxvillians already had a sentimental attachment to it. An organization called the Loyal Sons of the Grand Old Kiosk Protective Association proposed that it be kept where it was.

One letter writer, “A Citizen and a Taxpayer,” claimed that “If they move it, it will be over my dead body.”

Others proposed that it be refitted as a traffic signal at the troublesome intersection of Henley, Broadway, and Western; that it be moved to the Farragut Hotel corner to be filled with apples “to aid the jobless”; that it be refrigerated to vend soft drinks at the Caswell Park baseball field; that it become a hot-dog stand.

One group proposed that in spite of its weight, or maybe because of that, it be hauled to the top of Mount LeConte, to be a landmark hikers could behold, to touch and photograph, to prove they’d made it.

A letter writer, purportedly representing the Taxpayers’ League, suggested it be abandoned. They looked up the word “kiosk” in Webster’s dictionary, found it was a word for a Turkish summer house or pavilion, and “that if is allowed to go on, the next thing we know we will have harems in Knoxville—and where would the American home and our pure young woman and manhood be then?”

You might think professional weathermen would be more reverent toward it. However, Hubert Huff, the young meteorological observer whose competing measurements made two blocks away became immortal, noted “The Kiosk would make a grand peanut vendor.”

“Kiosk Leaners” outside the Custom House on Market Street at Clinch. (McClung Historical Collection)

Another U.S. Weather Bureau staffer, Sterling Bunch, recommended it ought to be fitted with a machine for telling fortunes. “Then we could go to the Kiosk, put in a penny and find out what the future holds.”

Its own future held something to do with the future of some of its Leaners. The government sold the Kiosk to Greenwood Cemetery, east of Fountain City, for a dollar. There, for 70 years, it served as a notice board for announcing funerals. Early in this century, an effort by the late pharmaceutical executive and historical-society stalwart Bud Albers brought it back where it belonged. Though recalled by very few who remembered its first incarnation, the Kiosk has been there for 15 years now, though maybe not quite the object of urgent daily interest it was 89 years ago, when Knoxvillians, too hot to do anything else, crowded around it to confirm that yes, it really was 112 degrees on the street.

~~~

I first read something about that Hottest Day Ever a long time ago—it became a legend, in my mind–and wondered if it would ever get that hot again. But in researching this column this week, I encountered a surprise. That day I’d heard about, back in July, 1930, was no longer Knoxville’s hottest day. The reading recorded by Hubert Huff back in 1930 had been beaten, twice, in my own time, and I should remember it.

The hottest day in Knoxville history was just seven years ago, on June 30, 2012. That day, the National Weather Service reported 105 degrees in Knoxville. That all-time record was tied the following day, July 1. It was on a weekend. I was here, working weekends downtown a lot in those days, and I always came out to the Market Square Farmers’ Market.

I should remember it. I don’t remember it. I’ve asked around some, and haven’t found anyone who remembers it specifically.

I looked it up in the daily. There was a front-page headline, and a thin, dutiful story that was mostly regional, obligatory interviews with the National Weather Service in Morristown and TVA. There were no reports of notable people suffering heat strokes or overcrowded swimming pools. That’s good, of course. But also there were also no man-on-the-street interviews, no observations of what people were doing to cope, no running jokes. Did anyone fry an egg on the sidewalk? If so, they kept quiet about it.

I was a newspaper columnist at the time, and would have written something to commemorate it. I might have even found a chef’s hat and a spatula and tried to make a manhole-cover omelet.

But in fact nobody told me it was the hottest day in Knoxville history. I probably stepped out of my air-conditioned house, and thought, hey, it’s pretty hot. But there was no Weather Kiosk to browse, and see just how hot it was.

Historians of the future won’t find much to say about how Knoxville coped with the hottest day in history. It’s the 21st century. We’ve advanced so far that we could have a weather disaster, and never know it. That’s progress, right?

Leave a reply