Editor’s Note: Comedian Dick Gregory died earlier this month at age 84. Many Knoxvillians may not remember that the civil-rights activist was, almost 50 years ago, at the center of a signal freedom-of-speech controversy at the University of Tennessee.

Ernest Freeberg, author of several nationally respected books of American history, most recently The Age of Edison, is chairman of UT’s history department. (As it happens, he’s also chairman of the Knoxville History Project’s board of directors.) Last spring, he was involved in the symposium “Intellectual Freedom at UT,” organized partly as a response to the Sex Week controversy that eventually involved even the state legislature. The exercise prompted Prof. Freeberg to look into this very interesting precedent, which between 1968 and 1970 involved several locally and nationally significant figures, including Judge Robert Taylor, already famous for his decision to desegregate Clinton High in 1956; future publisher Chris Whittle; maverick Chicago 7 lawyer William Kunstler; and Gregory himself, who did eventually get his chance to speak at the university. Freeberg wrote this essay, “Inviting Controversy,” about that dramatic era, and we’re happy to be able to publish it.

“They ask us to be non-violent, but this is the only country in the world that ever dropped an atomic bomb on Japan…It’s a cold day in America when anti-war demonstrators end up in court before a judge who manufactures war materials.” ~Dick Gregory – April 9, 1970

In 1968, Dick Gregory was among the nation’s best known black comedians, a civil rights activist, and a write-in candidate for president on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket.

The chancellor of the University of Tennessee decided he was also “an avowed extreme racist.” That’s the reason Charles Weaver gave when he banned Gregory from appearing on the UT campus that fall, canceling an invitation made by a student-run speaker committee. Letting Dick Gregory come to UT, Weaver insisted, would “tarnish the university’s prestige” and bring down the wrath of the state legislature.

That decision provoked a two-year fight over the limits of free speech on the UT campus that was finally resolved by a federal judge. Dick Gregory passed away on August 19th. But the legacy of his visit to the UT campus lives on, an important milestone in the development of intellectual freedom at the state’s flagship university. It is a story worth remembering as we face our own controversies over free speech on campus, here in Tennessee and across the country.

Undaunted by the chancellor’s veto, in the spring semester of 1969 the students tried once again to invite Gregory, and were again denied. “Whether he be for the cause of the Negro or the cause of the white man,” Weaver declared, Gregory was a racist, and should not be given a platform that would embarrass the university. After UT was organized as a statewide system, its president Andy Holt had appointed Weaver, a former dean of Electrical Engineering, as the Knoxville campus’s first chancellor. It was a daunting job, attempting to maintain order on a university that was exploding in size, and at such an explosive time in the nation’s history. Though well-liked by many of his colleagues, Weaver soon found himself caught between the conservative instincts of his twin bosses, Andy Holt and the state legislature, and the restive demands of students and faculty who wanted UT to change with the times.

Dick Gregory’s message was not the only one too controversial for UT’s leaders. This free speech fight began in 1967, when the administration blocked an invitation to Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the controversial black Congressman from Harlem. Temporarily barred from his seat by his House colleagues because of corruption charges, Powell launched a nation-wide tour that included a planned stop in Knoxville. UT leaders decided that Powell, in Congress since 1945 and perhaps the nation’s most powerful black politician, “did not qualify as a university speaker.” Campus leaders also refused to host LSD advocate Timothy Leary, even when students offered to raise his speaking fee with their own fund-raising drive.

What to administrators looked like responsible stewardship of the state’s flagship university looked to many on campus like censorship. “This land is troubled by serious problems,” one student wrote to the local paper. “A university which uses censorship to deny students access to various points of view leaves them ill-prepared to meet the challenges of these difficult times.”

A group of students, faculty, and administrators formed a “Student Rights and Responsibilities Committee” that called on UT to adopt an “open speakers” policy. Student groups should be able to invite anyone they choose, and the administration should “recognize the right of all students to engage in discussion, to exchange thought and opinion, and to speak or print freely on any subject whatever.” The university should only intervene, this committee proposed, in situations of “extreme tension.” In such rare cases, the administration could minimize the risk of violence by closing the event to the public and searching audience members for weapons. Both the student and faculty government endorsed this proposal.

Chancellor Weaver said he wanted an “open” campus too, but he asked the board of trustees to come up with a new policy that balanced free speech with his responsibility to preserve an “orderly academic environment.” Of course, a certain level of disorder was just what many students were looking for when they chose a speaker like Dick Gregory or Timothy Leary. As Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey put it when he spoke on campus during the 1968 campaign, this was “a year of rage.” Beyond the bounds of campus the war in Vietnam looked to a growing number of Americans like an immoral quagmire; the nation still reeled from the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy; for several summers running urban riots left cities in flames; and on more turbulent campuses to the north and west, students occupied administration buildings and boycotted classes.

As Weaver saw it, none of that turmoil going on beyond the “stately walls of old UT” provided any reason to change the campus’s traditional policy, that invited speakers should “be of a character and reputation somewhat equivalent to that of a typical faculty member.” But for those many college students in the late 1960s who found their curriculum irrelevant and their campus leaders stodgy, the last thing they wanted to hear were speakers that sounded like a typical faculty member. “Should the student learn only inside the confines of a classroom?” they asked.

Supported by tenure, college professors enjoyed both a freedom and an obligation to take on their society’s most controversial topics. But they were bound by the standards of their professional disciplines to do so in a measured way, informed by scholarly research and fair-minded about legitimate opposing viewpoints. If most professors talked in ways bound by academic decorum, students wanted to hear from speakers who were way out of bounds. What looked irresponsible and incendiary to campus leaders, and to many in the wider community, looked relevant and exciting to many of their students.

And students wanted the right to decide for themselves, instead of “merely being spoon-fed in the classroom.” As one champion of the open speaker policy put it, “If I am old enough to be drafted and sent out to fight a war, surely I’m old enough to make my own decisions on campus.”

But Chancellor Weaver doubted that students were mature enough to make responsible choices about campus speakers. An open speaker policy would produce what he called an “extra university,” free from the quality control imposed by the university’s wiser, mostly white-haired professionals. This parade of controversial speakers, from the left and the right, would provide little educational value, and would distract students from their studies. As another UT administrator put it, “students had difficulty distinguishing between intellectual distinction and momentary notoriety.”

A review of the speakers brought to campus in these years suggests a sea change going on in the intellectual and cultural life of UT in the 1960s, as it was on most other university campuses. In addition to many scholars now long forgotten, the students hosted some major figures in the intellectual life of the nation—the urban sociologist Jane Jacobs, the controversial behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner, and the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., for example. What place did a provocative comedian like Dick Gregory have in such a lineup? Today student groups regularly select high-priced speakers offered by agents who serve the collegiate branch of what might be called the “blather-industrial complex,” many of them best known for being known. But in 1968, the guardians of UT’s intellectual integrity could not imagine paying a significant fee (about $8000 in today’s dollars) to hear from Gregory, a man who wrote an autobiography he called Nigger, and who joked that, when elected president, his first act would be “to paint the White House black.”

What the students saw, and Weaver did not, was that Dick Gregory was a joker with a serious purpose. Since launching his career in the late 1950s, he had crafted an act that succeeded in talking to both black and white audiences about racism, commentary that he described as “saying out loud what I had always said under my breath.” Increasingly politicized by his involvement in the civil rights movement, Gregory offered a bittersweet laugh at America’s dark side. “I sat-in six months once at a Southern lunch counter,” he joked. “When they finally served me, they didn’t have what I wanted.”

Gregory broke the color barrier in both white nightclubs and late-night television talk shows. But over the course of the decade, he put ever more of his time and passion into politics, what he called “the struggle for human dignity.” By 1968, when the UT students asked him on campus, he was as well known for his activism as he was for his act.

In the spring of 1969, when Chancellor Weaver announced his decision to deny Dick Gregory’s invitation a second time, he explained that allowing controversial speakers on campus would rouse public opinion against the university, angering the legislators who paid many of UT’s bills. But many newspaper editors across the state sided with the students in protesting Weaver’s decision. The Knoxville News-Sentinel conceded that UT leaders should protect the campus from any speaker that might provoke violent disorder. But beyond that, “dissent is good.”

Chattanooga Times editor Martin Ochs scoffed at Weaver’s “disputable” charge that Gregory was a racist. “A kook, possibly,” but not a racist. And if the university was taking a stand against racist speakers, Ochs pointed out that the place to start would be a ban on visits from South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond and Alabama governor George Wallace. Censoring Gregory and stifling the students in this way was bound to backfire, Ochs warned.This heavy-handed approach would only energize the campus radicals, a handful of “troublemakers” in the middle of “all those thousands of moderate students, good boys and girls, on the Knoxville campus.”

This debate over the limits of free speech on campus prompted many in the wider community to weigh in with letters to the editor. Some denounced the irresponsible student “odd-balls” who were creating “an atmosphere of confusion” at UT, but many more offered rousing rebuttals. “If the university chooses each speaker based on its own ideas of right and wrong,” one asked, “how are students ever to learn how to reason with right or wrong ideas on their own?” Another wondered, “Are our colleges trying to teach a student to reason or are they merely turning out robots of conformity and stereotyped ideals?”

Pushback came from other sources as well. Julian Bond, the civil rights leader and Georgia legislator, had been invited to campus in place of Gregory, but he cancelled. “If one black man is unacceptable to the University,” his agent announced, Bond refused to be his substitute.

After some months of deliberation, the board of trustees gave the chancellor what he wanted. Rejecting the students’ request for an “open speaker” policy, they issued new rules that gave the administration veto power over any speaker whose presence on campus did not seem “in the best interests of the university.” The administration used this authority to veto another invitation to LSD advocate Timothy Leary.

Upset by Weaver’s interference, the Student Government Association organized a “speaker policy rally” on campus, led by SGA president Chris Whittle, later the founder of several high-profile media and education enterprises. Whittle and his fellow student leaders argued that whether Dick Gregory came to campus or not wasn’t the issue. The stakes of this debate concerned the very meaning of a university education in a democratic society. The SGA issued a Statement of Principle, laying out what was at stake: If students came to UT only to develop technical skills “or memorize a given set of facts in a subject area,” then the traditional classroom served that small-minded purpose well enough. But if the goal was higher, to “encourage students in the development of full civic and social participation, and beyond that, to educate the whole man,” then UT’s administration should be encouraging students “to tap the intellectual resources of whomever they wish to hear and believe they could benefit from.”

The Chancellor clearly worried that speakers like Gregory and Leary would provoke a “hostile reaction” from citizens, especially state legislators. Speakers were paid from student fees, not taxpayer dollars. But Weaver feared that this point would be lost on lawmakers who might seek to punish the university for inviting speakers whose views offended them. “In short, less money for UT.” But the students argued that a university should not allow itself to be bullied by “the dictates of the State…That the pursuit of truth should be circumscribed by government is not tolerable.”

Weaver refused to budge, and instead referred the matter once again to the board of trustees for an “in-depth study of the matter.” Tired of what they called “a masterpiece of official run-around,” a dozen students and faculty sued the university in February 1969. The administration’s heavy handed speaker policy was unconstitutional, they argued, and “made a mockery of UT’s function as the intellectual and cultural center of the community.”

On April 14, 1969, students and faculty packed into Knoxville’s federal courtroom to hear the ACLU’s famed attorney William Kunstler make the case that UT’s speaker policy violated the First Amendment guarantee of free speech. The New York Times described Kunstler as “the country’s most controversial and, perhaps, its best-known lawyer.” He had defended the Freedom Riders, Lenny Bruce, Stokely Carmichael, Martin Luther King, Jr., the Chicago Seven—and now the UT students who wanted to choose their own speakers. In the Knoxville courtroom, Kunstler took aim at the administration’s “insidious” policy that it reserved the right to decide which events were in UT’s “best interests,” a clause so vague that it gave administrators unlimited power to keep controversial speakers and their opinions off campus.

The UT attorney who rose to defend the policy told the judge that the university valued and promoted diverse viewpoints, but had no obligation to host any particular speaker. Students were not being deprived of their constitutional rights, he insisted, “even though they might not get the exact speaker of their choice.”

The “open speaker” coalition won the case. Agreeing with the ACLU, Judge Robert Taylor declared UT’s speaker policy denied the students’ First Amendment right to “receive information and ideas.” Taylor concluded, “It was the belief of our forefathers that censorship is the enemy of progress and freedom…The interchange of ideas and beliefs is a constitutionally protected necessity for the advancement of society.”

That victory came with a price for at least one faculty member who joined with the students in bringing the suit. During the controversy, UT history professor Richard Marius received death threats against him and his children. Ominous “we’re watching you” notes appeared on his lawn, and neighbors reported seeing strangers lurking in his yard at 3 AM. He bought a pistol and slept on the floor, ready to defend not the First Amendment but his family. “I got so tired of that,” he recalled two decades later. This was not the only time that Marius felt the wrath of conservative Tennesseans. Though popular with students, he was regularly denounced by citizens for his opposition to the Vietnam War, and his suggestion that Robert Neyland was not a good football coach. In the late 1970s he left UT to take a position founding Harvard’s creative writing program, while continuing a successful career as a historical novelist.

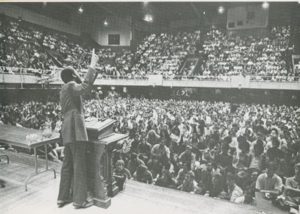

Thanks to that court decision, Gregory finally made it to the UT campus on April 9, 1970—two years after the initial invitation. Speaking to four thousand “wildly enthusiastic” students packed into the Alumni Gym (now Cox Auditorium), he told them that their parents were money-grubbing morons. “That’s why so many of you youngsters can’t communicate with your parents,” he explained. “They’re talking about money and you’re talking about morality…All these fools think about in America is a dollar.”

For well over two hours Gregory wound up the crowd. He praised them for belonging to the most moral generation of human beings ever, and they returned the compliment, punctuating his talk with a chorus of shouts, foot stomping and whistling. Far from inciting violence, Gregory advocated peaceful protest. “The police stations aren’t your real enemies,” he explained. “Your real enemies are the Rockefellers, the Kennedys, the Henry Fords, and the Du Ponts. After you’ve blown up all the police stations, they’ll still be around polluting your air and water.”

The night was marred by what the local paper described as “one minor incident.” Two white students in the balcony unfurled Confederate flags. After a brief struggle, a half dozen black students tore them down and ripped them to shreds.

Gregory offered some poor predictions that night. Nixon, “the dumbest white boy ever to be in the White House,” was going to lose his 1972 re-election bid in a landslide. And he shared some dubious conspiracy theories. (That’s a proclivity that Gregory indulged to the end of his life; he argued that the moon landing was faked, and that our government was complicit in the 9/11 attacks) That spring night in 1970, he told his UT audience that Nixon’s administration was waging war on marijuana because it was a drug that inspired young Americans to “tear up the country,” but that the feds were actively encouraging the sale of heroin, as part of Nixon’s secret plan to destroy first the black community and then “white kids.” “If kids can find the heroin pushers,” as he explained, “you know the Federal Government can find them. If they wanted to.”

Local media yawned, reporting that Gregory’s “rap” contained nothing that he had not said many times before. But a student publication declared that “only rarely has it been said all at once, and with such impact.”

The real impact of Dick Gregory’s talk had been felt long before he ever set foot in Knoxville. The administration’s speaker ban provoked two years of conversation on campus about the value of free speech, and helped students, faculty and administrators work through our democracy’s complicated balancing act between liberty and order. That conversation spilled far beyond the bounds of the UT campus. While public opinion on the matter is hard to gauge, a surprising number of newspaper editors and letter writers stood by the students, and defended the value of ideas they did not necessarily embrace. Though some wondered aloud what students might actually learn from an evening spent with Dick Gregory or Timothy Leary, they defended the right of college students to decide that for themselves. “Are we scared to death of a casual confrontation with the devil?” one asked in the local paper. “I’m like Mark Twain: I want to hear his side too.” And in the end, Chancellor Weaver made his peace with the open speaker policy. When parents arrived on campus the next semester to drop off their sons and daughters, some asked him how he intended to protect their children from the corrupting influence of radical speakers like Dick Gregory. Weaver explained to them that a federal judge and the First Amendment had already decided the matter. “If they are not in jail, they can come here to speak,” he explained. “Our only requirement is that they not be disruptive.”

Weaver soon came to appreciate a fundamental truth of the First Amendment, that it defends conservative voices as well as radical ones. When the chancellor allowed Billy Graham to use Neyland Stadium for a revival in 1970, some faculty members denounced him for turning the facilities of a secular, state university over to America’s most popular evangelical preacher–especially when Graham brought along his controversial and powerful friend, President Richard Nixon. Weaver took evident glee in this chance to inform these critics that he had no choice in the matter. Turning the football stadium into a platform for Billy Graham’s crusade, he explained, “demonstrates the essential correctness of our open speaker policy.”

When the state legislature recently passed a bill that aims to protect the free speech rights of students on our state campuses, they only ratified a policy already in effect at UT for almost five decades. It’s worth remembering that this was a right not granted by state lawmakers and campus administrators, but won by students who demanded a First Amendment right to decide for themselves whom they wanted to hear from. As the recent state interference with UT’s student-run and student-funded Sex Week has shown, a half century later the legislature remains more a threat to intellectual freedom on Tennessee campuses than its guardian.

Leave a reply