This winter several have noticed a bit of oddity in a surgical demolition project on the corner of Gay and Church. The greenish cube known as “the old KUB Building,” has been losing its skin for the last several weeks. As it did, it exposed, at the corner, curved steel beams in a shape you might expect to find in an ocean liner or maybe a World War II bomber, not in a square old office building.

This winter several have noticed a bit of oddity in a surgical demolition project on the corner of Gay and Church. The greenish cube known as “the old KUB Building,” has been losing its skin for the last several weeks. As it did, it exposed, at the corner, curved steel beams in a shape you might expect to find in an ocean liner or maybe a World War II bomber, not in a square old office building.

It’s an unusual tale. I’ll get to it here in a minute.

The square KUB building as we’ve gotten used to it was mostly built in 1964. It awed onlookers in the Great Society days. When the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night played down the street at the Riviera, it looked new and shiny and amazing. I was surprised to run across an assessment of it by Bert Vincent, the News-Sentinel columnist who was the first newspaperman whose byline I looked for when I was a kid. As it was completed in 1964, he remarked on it in his Strolling column. It was “a very pretty building,” he wrote. He didn’t often comment on new architecture, but this building was half a block from the Sentinel’s offices. “Can’t say why it appeals to me. One reason might be the light green glazed brick. It is easy on the eyes. Not too fancy, yet not antique.”

Easy on the eyes? Well, in 1964, maybe it was. You might have to remember the ties men wore to lunch at the S&W in those days to understand.

Was that the last nice thing anybody ever said about the KUB Building? It’s obvious that some forms of modernism don’t age well, and by the ’70s and ’80s, as the city was starting to rediscover an appreciation for brick-colored brick, the KUB building was starting to look like a fashion victim. In the ’90s, I wrote an article proposing that it be torn down, for aesthetics’ sake. It was a forbidding design, claustrophobic-looking, with windows made to stay closed. Maybe KUB, which championed climate control, wanted to support the idea that you never open windows. Use the thermostat.

Vincent found something to admire in its shade of green, even if it was one you don’t find in nature except in a neglected jar in the back of a refrigerator.

My uncustomary call for demolition drew unexpected protests, and caused me to rethink my own aesthetics, and then to work on a theory.

See, several readers loved the green old KUB building. All the ones I heard from were a decade or two younger than me. Some even told me they wanted to live there.

For me, it was an awakening, a dawning of a realization that should have come to me earlier.

We all hate the architecture of our youth. Preservationists are frequently perplexed by old men who admire antebellum and Victorian houses, but seem to viscerally hate buildings of the early 20th century. To them, craftsman style or art deco were not interesting and clever and historic, but embarrassing and old-fashioned and best left in the Dumpster. Their stodgy fathers and awkward uncles thought these things stylish, but since then we’ve moved on.

That’s one big reason we tear down good buildings, or sometimes just reclothe them, hiding or stripping the old exterior. Seeing the remembered past we’ve left behind, still hanging around like a party guest who doesn’t want to go home, undermines some folks’ idea of progress.

In condemning the KUB building, I was getting to be like those stubborn old men. I never saw the KUB building as an interesting artifact of history. It was from my own life, and I don’t think of my life as historic. It was just there, old-fashioned, like an unfortunate polyester tie, more embarrassing with each passing year. It was just there, old-fashioned, like an unfortunate polyester tie, more embarrassing with each passing year.

Those curved corner pieces complicate the story. That odd old building had several earlier personae.

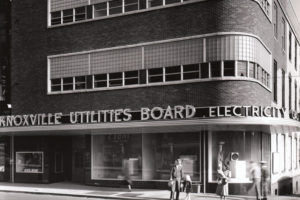

For about 13 years before the major 1964 makeover, the KUB building was a sleek, curvaceous, gracefully modernist building. The front of it, at least.

I don’t remember it. I first saw it in a discovered film taken from a moving car, showing the full length of Gay Street in the ‘50s. Nothing on the whole street surprised me so much. It looked cool, with a sort of wind-tunnel design, early ‘50s, pre-Jetsonian futurism.

In the 1880s, it had been a long brick furniture store. It became home to Knoxville Railway and Light in 1916. Not just an office building, it was a center for promoting the new electrical arts. Thousands of East Tennesseans went there to behold wonderful new home appliances. This building remained our power center even when the Tennessee Valley Authority changed everything in 1933, mutating it into the Knoxville Utilities Board, which distributes TVA power.

After World War II, everything was going modern, and it seemed as if an electric utility that promoted the modern should join the jet age. KUB redesigned the exterior in 1951 with curved beams for a streamlined modernist look, with long rows of wraparound windows.

However, the astonishing new facade just covered the Gay Street end. A few paces down Church, it was still the old building. It was like they tried to pull a short modernist sock over a long, old brick Victorian.

I’m not sure what Bert Vincent thought of that one. But by the early ‘60s, it reportedly had maintenance issues associated with old buildings. Back then there weren’t tax credits for using historic buildings, or organizations advocating for them. And KUB needed a bigger building.

So it was that just 13 years after that extraordinary makeover, KUB chose to increase the building in size, adding a fourth floor and a simpler fortress-like design.

Now, the prolific advertising firm Tombras is moving in, creating one of the first new office spaces downtown in several years. Sanders Pace’s design presents a metal exterior, vertical windows, and sharp angles concealing those 1951 curves. It’s early 21st century modernism.

We’ll like it. Our kids will hate it because we liked it. Our grandchildren will like it again. It will become fascinating.

Leave a reply