The Twenties Revisited

Knoxville’s Lost Generation presents a challenge for ours

By Jack Neely

It’s the ’20s again. Who would have guessed?

What we remember as the ’20s–the postwar flowering of culture known as the Jazz Age in music, the Flapper Era in fashion, the Roaring ’20s in business, and the Lost Generation in a certain genre of literature–bloomed after the horrors of the Great War.

All the names evoke images that fit together: Ernest Hemingway, Louis Armstrong, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Babe Ruth, Cole Porter, Charles Lindbergh, Dorothy Parker, Fletcher Henderson, Gertrude Stein, Walt Disney, Bessie Smith, George Gershwin, Countee Cullen, Charlie Chaplin, John Dos Passos, Josephine Baker, Pablo Picasso.

The Lost Generation seems a very odd name for these folks–to posterity, they’re not lost at all; a century later, they still dominate. Most of them have handy biographies, some of which were bestsellers. And how many movies and documentaries have there been about those folks, just in the last 25 years? Midnight in Paris, which deals with about a dozen figures of the 1920s Lost Generation, came out in 2011, and is Woody Allen’s most popular film of this century. The last of several movie versions of The Great Gatsby was a 2013 film starring Leonardo DiCaprio that, despite mixed reviews, was a blockbuster with a young audience. It’s a safe bet that more people in 2020 have read The Great Gatsby than most bestselling novels published in the last 50 years.

You still hear 1920s music everywhere, on soundtracks, even on TV commercials. People have 1920s parties, and most people–even people who are now actually in their 20s–seem to know, roughly, what to wear. Though from looking at society pictures, I get the impression that a lot of older businessmen think the ’20s was mainly about wearing a hat–any sort of hat–and wearing it inside. (That’s a distinction maybe lost on moderns attending ’20s parties–in the real 1920s, to judge by old movies, a man wearing a hat indoors was usually a police officer in a hurry.)

We think of the 1920s as a fun time we wish we could have joined, though it came only after the trauma of war and an extremely deadly pandemic, and in some ways it was a time of hardship and denial. Alcoholic beverages, even beer, were officially illegal everywhere. The economy didn’t boom everywhere; there was an agricultural recession that sent thousands of unemployed rural people into the cities, including Knoxville.

It was also an era of the rise of the mutation and resurgence of a half-forgotten terrorist faction called the Ku Klux Klan; reconstituted as a “patriotic” nativist organization, it has never been more popular before or since than in the ’20s. America was just beginning to grapple with racism, a condition so common it didn’t even have a name yet.

The Spanish Flu was over, barely, but we were just beginning to worry about a mysterious new disease called polio. It swept through cities in the summertime, killing or crippling mostly children, but occasionally adults, as in 1921 when it permanently disabled former presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt.

Still. The ’20s did have an unusual electricity to it, and something about the era, at least partly driven by new technology, including radio and sound film, along with a new cultural influences outside the old white-protestant American norm, inspired a generation of artists so groundbreaking they’re remembered today.

When we think of the Lost Generation and the Jazz Age, we tend to think of Paris and New York. But there was ferment in lots of other places, including Knoxville. That’s what we may have forgotten.

Some of the local resonance of the ’20s is obvious. The Scopes trial, 70 miles away in Dayton, captured the nation’s attention in the summer of ’25. One of Scopes’ attorneys was a well-known Knoxvillian, the recently fired UT professor John R. Neal. And the more-famous Clarence Darrow tarried in Knoxville for a few days just after the trial, as Knoxville greeted the funeral train of William Jennings Bryan.

South Knoxville’s Lindbergh Forest (a neighborhood off Chapman Highway) was named as the result of a citywide contest promoted in the newspapers in 1927, just one month after Lindbergh’s flight. Hemingway’s latest novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, praised in the local papers, were for sale in the Miller’s balcony. And if college football were not such a national craze in the sis-boom-bah ’20s, when the game was suddenly almost as popular as bathtub gin, would we have Volmania today? I can only say it started here then. Shields-Watkins Field, UT’s first regulation-standards football field, was finished after major investments in 1921–and Capt. Robert Neyland arrived from West Point in 1925, soon to make the Vols so impressive their games began to attract some non-students.

I can’t claim we had a Montparnasse, a Deux Magots or Cafe de Flore, but Knoxville had its share of cafes. “Tea rooms,” aimed mainly at women, were the rage, places for debutante parties and bridge games and circle meetings. There was a Fort Sanders Manor Tea Room, an Arnold Hotel Tea Room, a Fifth Avenue Tea Room–and, for black boulevardiers on Vine Avenue, the Pan-American Tea Room.

The Blue Triangle Tea Room, often mentioned in the society pages, sounds intriguing and mysterious until you realize it was at the YWCA, and named for their logo. Its glass-enclosed porch was famous. A place called Tinker Tavern was not a tavern at all, but a cafe on Henley Street, one with the extraordinary distinction, heralded on a plaque, that it was a former home of Frances Hodgson Burnett. The novelist and former Knoxvillian died in 1924, but her works inspired seven different feature films released in the 1920s from that new movie factory called Hollywood. (Among them was Little Lord Fauntleroy, starring Mary Pickford, who obligingly bent her gender a bit for the title role.)

One especially interesting Knoxville cafe was run by one Emma Farr, who raised chickens and sold eggs on the east side of town. The wife of a Southern Railway machinist, she opened a whimsical cafe called The Pollyanna, from the 1913 novel about a cheerful orphan: it had recently been made into a movie with Mary Pickford in the title role. The Pollyanna opened first in the Newcomer building, the department store building that we now know as Mast General Store. More about her later.

Things were happening here while former Knoxvillians were creating the ’20s as the big-city world knew it.

Feminist journalist Ruth Hale (1887-1934), member of the celebrated Algonquin Round Table in New York, was from Rogersville and spent several years of her youth in turn-of-the-century Knoxville. (She’s depicted in the well-regarded 1994 film Dorothy Parker and the Vicious Circle.)

Paul Y. Anderson (1893-1938), originally of the Island Home area, was one of the major national journalists of the era, won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 1929, for explaining where the bodies were buried in the Teapot Dome scandal. He also reported on the Scopes Monkey Trial for a national audience–as did Joseph Wood Krutch (1893-1970), a Knoxville-born writer, UT grad, even, who came to the fore in the ’20s.

Just a little older than Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Krutch is never grouped with the Lost Generation. He was too certain of his opinions to consider himself lost, and he wasn’t much of a joiner, anyway. But his name became familiar in New York when he wrote a series of essays about the Scopes Trial for The Nation in 1925. Before the decade was over, he was also known as a drama critic and biographer.

His postwar cynicism would likely have earned Krutch a cafe chair alongside the existentialists of Paris. Krutch’s book about his era, The Modern Temper, in 1929, was considered a classic at the time, even if it’s forgotten today. It was a profoundly pessimistic work, asserting that both God and science had proven disappointing, and that man’s aspiration to rise above his animal needs was irrational. Mankind didn’t have enough, and needed more. It was so shocking it made headlines from Boston to Honolulu. As it caused an international stir, Krutch was in town at least once a year to spend time with his mother, who lived on Cumberland Avenue near UT. (His Uncle Charles was the noted artist; his older brother, also named Charles, was an artistic photographer who lived here, too.)

***

But whether those former Knoxvillians in New York knew it or not, things were happening here, too.

Radio was energizing everything, and thanks to teenager Stuart Adcock, by 1922 Knoxville had a lively station, and soon another to compete with it. By the end of the decade, the city’s musical ferment was such that popular record label Brunswick sent jazz pianist Dick Voynow to spend a few months in a professional studio in the St. James Hotel to make records of what was going on here.

Today, on the rare occasions when historians talk about Knoxville in the ’20s, it’s likely to be about country music. Not yet called that, whatever it was coalescing: when both phonograph recordings of folk music and radio arrived in America almost simultaneously, that tradition-derived music was getting some attention, as musicians who had been content to make their living as guitar-playing buskers at the train station, like Charlie Oaks, George Reneau, and Mac and Bob, as well as better-known performers like Uncle Dave Macon, were now being sent on the train to New York to make records for Sterchi Bros. Furniture to sell. (Roy Acuff, who hadn’t yet given up on a baseball career, was just learning the fiddle.) They were among the first country-music records ever made, but weren’t an immediate hit. In the summer of ’25, Sterchi’s put them on sale for just 50 cents each.

It was no way to make a living. Blind guitarist and singer George Reneau was one of Knoxville’s first recording artists when he was arrested repeatedly for begging in the streets. In 1929, the city finally offered him a permit.

But country wasn’t mostly what you heard on the radio in the ’20s. Often you’d hear classical music. Cincinnati-trained violinist Bertha Walburn Clark was evolving local talent, by degrees, toward a symphony orchestra. In the 1920s, her “Little Symphony” of about 25 musicians regularly performed at the Farragut Hotel, as Sergei Rachmaninoff, Jascha Heifetz, and Ignacy Paderewski made appearances at the Lyric down the street, much of that thanks to an well-connected young lumber executive from England named Malcolm Miller, who became our host of the performing arts.

Marian Anderson performed there, too–a year before her first concert at Carnegie Hall–as well as tenor Roland Hayes. Before the 1920s, it was unusual to see black performers take center stage at what was mostly a white theater. Those two concerts were sponsored by a black women’s society called the Altruistic Club.

But more than anything what you’d hear in the ’20s was something new. Howard Armstrong and Carl Martin, who lived together on Yeager Street on the east side of town, were using country instruments to make interesting music that sounded like jazz. They formed a unique combo called The Tennessee Chocolate Drops that performed almost everywhere, at barber shops and pawn shops, at black dances and white dances, and live on local radio, and even made some recordings. In 1931 they moved north to surprise Chicago with their sound.

Leola Manning, an East Knoxville cafeteria worker, was singing a plaintive new form of music she didn’t like to call the blues. She stayed, becoming better known as an evangelist.

A white jazz orchestra called Maynard Baird’s Southern Serenaders was arguably Knoxville’s first Big Band. They toured, broadcasted, made a few records for Brunswick, and had a following up north, but remained Knoxville residents and often played at Whittle Springs Hotel or the Riviera Theatre. Although country music’s roots in the 1920s are interesting to cultural historians, Knoxville’s most popular music was, without rival, jazz.

It was at all the parties, in the speakeasies, in the country clubs, on the vaudeville stage. Jazz bands would play at real-estate auctions, at openings of shoe stores and dental clinics and Miller’s toy department, at automobile dealerships, and with surprising regularity between boxing and wrestling matches at the Lyric Theatre. They were always at the unique gazebo at Neubert’s Springs in South Knox, playing for “open-air dances,” and at Whittle Springs Hotel in North Knox, under someone more formal circumstances. Or late at night, sometimes until dawn, at the Wayside Inn in Bearden, playing for gambling, drinking, dancing locals and tourists alike. On special occasions, riverboats would leave downtown towing a barge with a jazz band and enough floor space for dancing. When the Tennessee Theatre opened in 1928, a jazz band was there to welcome visitors to the movies, and returned every night for months to come. Occasionally well-known jazz performers would show up there before a movie, like Georgia crooner Gene Austin, who was on the Tennessee’s stage several times.

The black-audience Gem Theatre at Vine and Central had a house band, a “colored orchestra,” about which I wish we knew more. Eventually the Gem hosted big jazz-age stars, like pianist Earl Hines–and, if there’s any truth in old stories, Bessie Smith and Billie Holliday, in shows that probably weren’t mentioned in the white press. (Georgia-born Ida Cox, one of America’s biggest jazz/blues stars of the 1920s, spent the last 20 years of her life in Knoxville, but may have performed here only once, at the Gem in 1930.)

***

Knoxville was starting to look different, even its skyline.

The Andrew Johnson Hotel, designed by Baumann and Baumann, was completed in 1928, and was at 17 stories the tallest building ever built in East Tennessee, a title it held for almost half a century. Originally called the Tennessee Terrace, it was perhaps too hastily renamed in 1929, at the suggestion of Greeneville author Irene Bewley, when a revisionist history came out hailing Andrew Johnson was a great American hero.

The Tennessee Theatre, the Moorish-revival “motion-picture palace” designed by the briefly stylish Chicago firm and finished almost simultaneously with the tall new hotel, could not have been built in any other decade. It’s a survivor of a brief architectural trend. The Tennessee was also the only theater to employ a staff artist, the resourceful and prolific Joe Parrott, who kept his studio near the dressing rooms, and twice a week constructed almost-architectural promotional creations for the lobby.

Charles Barber was coming into his own, a young architect taking an almost playfully imaginative stand against modernism with creations in brick and stone that evoked the Middle Ages with balconies and spires and castellated ramparts, as if building sets for Douglas Fairbanks movies. During the ’20s, he designed the new YMCA–followed by the cathedral-like Church Street Methodist Church.

His opposite, perhaps, was the unremembered designer of the Daylight Building. Built on Union Avenue in 1926, the long, low building with so many windows was a novelty, and tended to attract young, creative entrepreneurs. Louise Mauelhagen, a rare New York-trained fashion designer, opened her dress shop there. W.A. Carroll painted commercial signs, but advertised his skills by filling his shop with actual paintings, framed on the walls. Same with another artsy business, The Picture Framery, also in the Daylight, which mounted shows at least occasionally, like one of Chicago impressionist Vivian Hoyt. Robin Thompson distinguished himself from his big brother Jim by combining photographic skills with the young man’s obsession of the era, airplanes. Knoxville’s pioneer aeronautical photographer, he had learned his unusual art during the Great War. He established his studio there early on; when he wasn’t up in the air, he was down at the Daylight.

The Daylight Building on Union Ave, circa late 1920s, early 1930s. (Courtesy of McClung Historical Collection)

It shouldn’t be surprising that the Daylight featured some art shows, and was at least sometimes a center of cultural activity during that era.

Emma Farr, the chicken-farming owner of the Pollyanna whom we mentioned earlier, moved there, too, opening in a larger space at the new Daylight, decorated in green, black, and orange, with a balcony, presumably in the back. Open in late 1929, it accommodated 100, with a staff of 14. She opened at 7 every morning, serving coffee, tea, waffles, and biscuits.

She had a remarkable son who had just spent some time in Paris.

***

Every week seemed to bring a bizarre surprise.

Female impersonator Julian Eltinge performed at the Bijou in 1924. In 1925, the latest craze was the “Manless Dance,” attended only by young women, some dressed as men, some as women. Perhaps even crazier was the new rage for miniature golf. Courses were popping up everywhere, as if mocking the big courses. Daredevils were testing progressively odd new flying machines, some with only one wing, and landing them in Bearden. A few daring restaurants were even serving chop suey.

In 1924, people came out to see Chicago’s poet, Carl Sandburg. He surprised his crowd; instead of solemnly reading his poetry and prose, he played some banjo; he borrowed a typewriter at a downtown newspaper office long enough to bang out another chapter of his Lincoln biography.

There were rules against drinking, people ignored them, and there weren’t many other rules. People sometimes even ignored the color line. A black woman named Fanny Lane refused to give up her front seat on the Lyons View trolley.

It might be a stretch to say Knoxville had a literary scene in the ’20s. Asheville’s Thomas Wolfe briefly mentioned Knoxville in Look Homeward, Angel, but we had no equivalent here. Then again, Lucy Curtis Templeton started writing for the News-Sentinel in 1927, beginning almost half a century of sharing her generally enlightened views about books, local history, and the natural world. Bert Vincent moved to Knoxville from Kentucky in 1928, and began describing the city more intimately than anyone else had before, in his “Strolling” column. John T. Montoux, Steve Humphrey, and eccentric old Patty Boyd, said to be the most durable newspaperwoman in America–with two competing daily newspapers–sometimes three!–it was the beginning of a Golden Age for newspaper writing in Knoxville. They all seemed to find the old place fascinating in ways that previous generations had taken for granted. A fresh column called “Gwen to Fifi” makes Knoxville sound like a lively place for both gossip and the arts, as if they were roughly the same thing.

For a year and a half of the ’20s, the teenager James Agee was a student at Knoxville High. After he moved north in 1925, to a private school at New Hampshire’s Phillips Exeter, he would lampoon his time at the overcrowded public school in his first short stories.

In one story he refers to Helen Mundy, the energetic and strong-willed Knoxville actress who thanks to the fact that she and her Knoxville High friends were holding court in a downtown drugstore in 1926 when offbeat director Karl Brown walked in, appeared in an unusual naturalistic movie called Stark Love, briefly to be a national sensation, only to vanish in a way characteristic of the era; she quit show business to marry a jazz bandleader.

Playwright Tennessee Williams would not be known by name until 1945–but Tom Williams, who was the same guy, was an observant adolescent frequently seen in Knoxville in the ’20s, a St. Louis resident who was here often enough with his Knoxville-born dad that people knew him by name. His sister, Rose, was much more familiar here, where she stayed for weeks at a time, attending dozens of extravagant but mostly disappointing debutante parties.

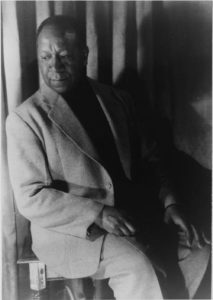

Beauford Delany (1901-1979) (Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

Personally flamboyant and unconventional, genius artist Beauford Delaney became emblematic of the spirit of bohemian New York in the late ’20s, and maybe a catalyst of it. He was well-known in Knoxville first, though, the colorful young shoeshine at a popular cobbler, known to some for his jokes, and ultimately to others for his art. He was celebrated in Knoxville even before he left to study art in Boston in 1923, after some years of working as an apprentice with elderly Lloyd Branson, Knoxville’s first professional artist, who in his 70s still kept his studio on Gay Street near Clinch. Delaney would gain international fame for both his portraits and his abstracts, but one of Delaney’s first notable paintings was a Knoxville landscape from about 1922.

Beauford’s younger brother, Joseph Delaney, was in and out of Knoxville in the 1920s, but earned praise as a child for his drawing, and eventually made a name for himself as an artist.

Knoxville in the early ’20s had another acknowledged artistic celebrity. Then in her 40s, the well-connected Catherine Wiley was niece of the California senator and former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, William Gibbs McAdoo, who was running for president in the ’20s. But Wiley was Tennessee’s most accomplished impressionist, doing most of her work in Fort Sanders, at the White Avenue studio she shared with her sisters, May and Eleanor, who were artists themselves. But in the early ’20s, perhaps as the result of the successive deaths of her father, her brother, her mother, and close mentor Lloyd Branson himself, Catherine’s work was turning darker and more chaotic in tone. She suffered a mental breakdown in 1926, and was institutionalized in Philadelphia for schizophrenia. (After mention of one more award for her art, at a show in Nashville in 1927, she was never mentioned in print again until her death, over 30 years later.)

By then, the once-dynamic Nicholson Art League, of which Branson and Wiley had both been leading members, seemed to be coming apart. But other things were budding to take its place. Some of the Italian-immigrant stonecutters who had moved here to work with Tennessee marble became something more than stonecutters, more like sculptors. Leading them was Albert Milani, who had been working here for several years before 1927, when Candora marble hired him as their resident sculptor.

A few interesting younger artists were doing fresh new things without permission from their once-celebrated Edwardian elders. At the center of it was one older artist who didn’t retire or move away.

***

Described as “lean, outspoken, and somewhat eccentric in mannerism and views,” Robert Lindsay Mason had studied in Philadelphia with popular and sharply distinctive artist-illustrators Maxfield Parrish and Howard Pyle. But Mason made the choice to stay in Knoxville, one of the younger members of the Nicholson Art League, exhibiting his own art during the Exposition era, running a studio and art classes on East Church Avenue, where he was often found to be conversing with a close friend, a visiting Cherokee leader. Mason had a stylish style, impressive to young people who came to study with him.

His studio became a meeting place for the East Tennessee Fine Art Society–an organization that may have existed only in the 1920s.

In May, 1927, their “Spring Exhibition” was held at the Daylight Building, featuring the work of Mason himself–as well as that of some of his studio comrades. Some of the exhibitors were already well-known artists. One was a New Yorker, former Knoxvillian Hugh Tyler, uncle of author James Agee, who would refer to Tyler in several of his works. Another was the quiet, elusive, but prolific Charles Krutch, “the Corot of the South.

Mary E. Grainger, former member of the Nicholson Art League and the admired head of the art department at Knoxville High, had work at that show. Daughter of an English immigrant, she had studied at the New York School of Art, where Robert Henri was a teacher and Edward Hopper was a former student. For decades she lived alone on Luttrell Street and painted portraits, landscapes, and later murals.

Decie Merwin, another participant who would spend most of her life in New York, would become a nationally known children’s book illustrator and sometime author. She had earned praise in the Knoxville press since 1925, when some of her work appeared in Ladies Home Journal.

West Barber–an architect cousin of architect Charles Barber, “West” was there, too; in fact, he was sometimes president of the E.T. Fine Art Society.

Even the rebellious young often gravitate around an older mentor. In 1920s Paris, for many, it was Gertrude Stein, whose museum-like studio attracted artists and conversations. In Knoxville, maybe it was Robert Lindsay Mason’s studio. As it happens, he was born the same year as Stein.

It may be pure coincidence that Mason’s studio was on the same hillside and just a couple of blocks away from the family home of Beauford and Joseph Delaney. But Mason and the much younger Beauford Delaney almost certainly knew each other, because they were both close to Lloyd Branson.

But others, like Mary E. Grainger, had surprising influence through the public schools. One of her students, Frank Long, was just a kid best known as a high-school athlete when the Picture Framery at the Daylight Building mounted a show of his work, a year after that landmark show by Mason’s group. The show mounted several framed oils, pastels, and pen-and-ink drawings by Long. According to the News-Sentinel’s “Gwen” columnist, “No need to speak words of praise for Frank Long, artist and former Knoxville High School student, for his pictures speak for themselves. And the story they tell is that Knoxville has sent forth a real artist.” It may have been his first public show.

Long was on his way to Paris, though; on his return less than two years later, his work would cause anxiety for its “ultramodernism.” But he was one of several who would make a living as a career artist, and whose work is known and appreciated today.

The group had lots of avenues of influence from the world’s centers of culture. Optician O.C. Wiley was well-known among local artists because he was a pioneering dealer in cameras and other optical equipment. His daughter, Elizabeth Wiley Dunlap, had spend part of the early 1920s in Paris. She became a landscape architect who helped design parts of the new neighborhood soon to be called “Sequoyah Hills,” and has been credited with Knoxville’s first modernist home, on Scenic Drive. She also exhibited her artwork alongside Mason’s followers.

Some of the students who came out of Mason’s studio became well known. One was East Knoxvillian Dave Huffine, a teenager at Knoxville High, later art director for UT’s humor magazine, The Mugwump. Because Huffine would soon make a career as a national-magazine cartoonist in New York, he would often be cited by newspapers as Mason’s most famous student.

Another of Mason’s students in the ’20s was an unusual artist I’ve learned about only in recent years, through the Knoxville Museum of Art, which has exhibited a couple of his striking paintings. His name was Charles Griffin Farr. Neither abstract nor traditional, his paintings are stark and sharply different from the paintings of any artist who ever came out of East Tennessee.

Son of Emma Farr, the cafe owner, he was a sensitive Central High kid who regarded an older student named Roy Acuff a “ruffian.” He wasn’t the only one who felt that way; before Acuff found his place as an extremely influential artist of his own stripe–a bold and transformative fiddle player and band leader–Acuff was an aggressive athlete and a tough customer, sometimes arrested for gambling, bootlegging, and assault. Farr was an athlete, too–one of several young people who signed up to “Swim the Channel” at the YMCA pool, approximating the length of a real English Channel swim–but art was his passion. If Farr really did know impressionist Catherine Wiley, as family lore holds, he knew her only as a teenager; the year he graduated from Central High, she graduated to the mental institution in Pennsylvania. But for an ambitious kid, the genius of White Avenue was one to meet.

He definitely did study with Robert Lindsay Mason, probably ca. 1926-27. Next he went to New York and the famous Art Students League, the first of several Knoxvillians to join that group. For a year he studied with ashcan realist George Luks and anatomy specialist George Bridgman. In 1928, Farr left for the Paris of Chagall and Picasso and Ravel, of Josephine Baker and James Joyce. There he studied mostly with Jean Despujols, a master of modern realism. (While he was there, he might have run into another Knoxvillian studying art the same year: former Knoxville High track champion Frank Long, who would make a career in public art.)

When Farr returned the following summer, he found that his familiar hometown had produced one interesting place to work.

In 1928, the last remnants of the Nicholson Art League purchased one of Knoxville’s prettiest old houses, the antebellum fantasy Melrose, on the hill to the west of the university, with its Italianate tower, and dubbed it the Melrose Art Center. It had a cafe, new art on the walls, and statuary on the lawn. It didn’t last long, but neither did most things in the ’20s. Young Charles Griffin Farr, later known in California for his modernist realism, exhibited there in the late ’20s–and, perhaps having learned a few things from his mom, worked as a waiter in the coffee shop.

If you were to capture the idealistic aesthetic spirit of the era in one setting, you could hardly do better than the Melrose Art Center. In late 1929, it featured an exhibition of the work of Charles Christopher Krutch, Dave Huffine, the late Lloyd Branson–and Charles Griffin Farr, who might also be serving your coffee. A few months later, Melrose featured the work of Frank W. Long, who had begun his study at KHS with Mary E. Grainger, but later in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Paris. His modernistic submissions sent “a quiver of doubt and perplexity” over the governance of the museum, which ultimately rejected four of his abstracts. For many years, Long was a Berea-based muralist; his work now hangs at the Smithsonian.

Farr’s original mentor, Robert Lindsay Mason, was still around, Knoxville’s authority on art, but by then he was notable for a popular book. All along, Mason had doubled as a writer of newspaper pieces, often with a bit of adventure involved, and one remarkable book. Today Mason may be best remembered less an artist than as the author 1927 book called The Lure of the Great Smokies. A modern and poetic evocation of a little-known region, it got some national attention and made Mason famous, for about a month at least. Still available in the library and in rare-book shops, it’s a classic that can still surprise the unsuspecting.

Mason had some background on the subject, as one of the first Knoxville artists to venture into the mountains. Back in 1917, he had given a talk to the Nicholson Art League, “Experiences of an Artist in the Smokies.” Chances are, most of those in his audience had never been there. Despite the proximity, the Smokies had been terra incognita to most Knoxvillians, who could see them at a distance, on a clear day, but hard to get to, for most people, and mostly privately owned. The first dependable paved roads to the Smokies were built in the 1920s.

Shorthand accounts of Smokies history put the park’s founding in 1934, and its dedication in 1940, but it was very much a product of the 1920s, which saw most of the inspiration and perspiration that made it happen, when much of the city’s creative energy was focused on that distinct and previously little known region to the south. When Clarence Darrow was here in 1925, he wanted to see the Smokies, and stayed at Elkmont. When Will Rogers came to town in 1926, he was excited about the park project and wanted to see it, too.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park inspired writers and artists, maybe as much as the city of Paris did. In the days when a Knoxvillian taking a long hike in the Smokies was so unusual that it rated a short article in the newspaper, many of those early newsmakers were aspiring artists.

Mason’s students Farr and Huffine got especially interested in the Smokies–Huffine worked in the mountains for a time as a surveyor of the new park. Most of that generation shared the excitement: photographer Jim Thompson and his aeronautical brother, Robin, became famous for their never-ending attempts to evoke the Smokies on film.

Florist Brockway Crouch was an important early supporter. Harry Ijams became famous to future generations for his natural sanctuary by the river, but he was a professional artist by trade, and frequently depicted the Smokies in his work. Mary E. Grainger, the teacher who was a close friend of writer Laura Thornborough–whose 1937 book The Great Smoky Mountains became the first classic work of literature about the mountains since Mason’s–would spend entire summers up there, painting. Maverick architect Charlie Barber was an adventurous multi-day hiker. Leading many expeditions was talented writer Harvey Broome; he spent much of the decade at Harvard, getting a law degree that would be useful to him a few years later when he co-founded the Wilderness Society.

Older than the rest of them was Charles Christopher Krutch, known as the Corot of the South. He was an old man, old even by the standards of the Nicholson Art League of which he had been a member, but the ’20s may have been his most productive era as an artist. He spent weeks in the mountains alone with his paintbrush. Many Knoxvillians had his oil paintings of the Smokies in their living rooms before they ever saw the mountains up close.

They all did things in town to promote the Smokies, many of them with artistic depictions. Several of them actually worked in the Smokies, as volunteers working on surveying crews, planting seedlings, cutting trails.

The Smoky Mountains had been the major theme of that May, 1927, exhibit at the Daylight Building. In the spring of 1928, the Home Building and Loan office on Clinch Avenue hosted a special exhibit of paintings of the Smokies, most of them by professionals, including Krutch, Mason, and Hugh Tyler.

Dave Huffine, the future cartoonist, was younger than the others. He had first gotten in print at age 16 when he climbed Mt. Le Conte with a small party that included Mason, celebrating the publication of his book. Also a hiking buddy of his cousin, future Wilderness Society co-founder Harvey Broome, before the national park was officially open, Huffine eventually worked in the Smokies as a surveyor and guide.

Huffine and Broome were among the first locals to climb one of the Smokies’ highest peaks, a remote mountain south of Mount Guyot, not yet reached by any trail. They named it for themselves, taking letters from the names of their party of four. Mount Lumadaha, they called it–the Da was for Dave, the Ha for Harvey. For about four years, the whimsical name seemed to be catching on. It yielded, in 1931, to a more solemn era. The authorities chose to call it Mount Chapman, for Park co-founder Col. David Chapman.

In the early ’30s, Dave Huffine went on to join the Art Students League in New York, in fact was a member about the same time that Joseph Delaney was, when the latter studied with Thomas Hart Benton and began a career dominated by colorful urban scenes, on at least one occasion reaching back to a vivid memory of his Knoxville youth, for his “Vine and Central.”

In New York, Huffine married another artist and made a living on his drawing talent and dry wit; his “gag” cartoons would appear in several national magazines, including Colliers, The Saturday Review, Esquire, and The New Yorker, as well as books. He always said he wanted to move back, but the work was in New York, and he spent most of his time in the Catskills, the handiest substitute for the Smokies. He died in Woodstock at age 64.

Charles Griffin Farr eventually moved to the West Coast, where he became an award-winning “California realist” painter in the Bay Area, an odd duck as a serious artist in the era of abstract expressionism. Before the term “magic realism” was used for literature, the phrase appeared in a 1951 issue of the San Francisco Examiner and later in the Oakland Tribune to describe his painting called “A Street in Knoxville.” The ominous setting for that painting, now at the Knoxville Museum of Art, appears to be a downtown intersection in the 1920s, perhaps Fifth Avenue near Gay.

Farr returned to Knoxville occasionally, sometimes just for a modest exhibit in a bank lobby. He was here for the World’s Fair, but by then was not nearly as well known in his hometown as he was on the West Coast. He later struck up a personal acquaintance with another artist of street scenes, Joseph Delaney. They had both lived in Knoxville in the ’20s, but it’s unclear whether they knew each here then. The younger Delaney spent most of the decade in Chicago, but returned to town for a year or so in 1929, and may have noticed the excitement stirring around Mason and his coterie.

You could argue that that conservationist cadre was more creative than any cafe full of expatriates in Paris. Knoxville’s younger generation of energetic, creative people, could never seem very Lost, because they had a focus for all that creative energy.

Mason and his allies were about the same age as the artists and writers who hung out at Montparnasse. But instead of ordering a third round of cappuccinos, they were swinging mattocks in the Smokies, and created a sanctuary for plants, animals, and people that will last for centuries.

So it’s the ’20s again. What are we going to show for it?