The Ragged Edge: Christmas 1920

Fire-Vomiting Oysters, the Midnight Frolic, and Glookum

It was a new decade, after a previous decade of war that modernized old-world antagonisms with industrialized slaughter; of ruinous riots based on race hatred; of global pandemics, especially the last one, which was the deadliest in history.

A new decade promised to overcome all that by making the whole world modern, partly by ignoring the past with the help of fresh distractions. Probably only the second decade in American cultural history (after the Gay ’90s) to develop a strong cultural identity, the 1920s were an era of radio, jazz, football, bobbed hair, absurd dances, and a new curiosity about other cultures beyond the white mainstream, from blues to cross-dressing to chop suey.

But we still had Christmas. After generations when the ancient holiday was, by turn, ignored altogether, or over-celebrated with disastrous liquor-fueled riots, by 1920 Christmas had become something we’d recognize today. People were getting Christmas trees, putting presents under them, and spending more of the holiday at home.

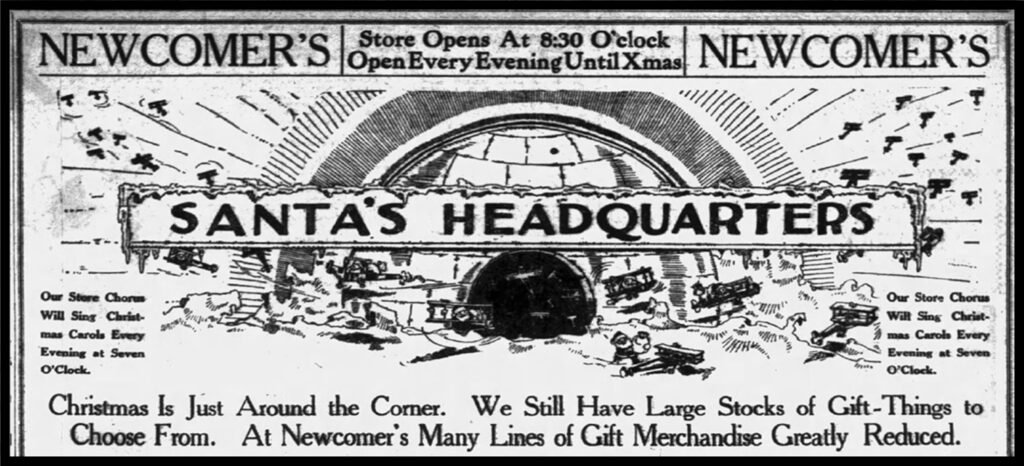

In fact, a lot of the places that were familiar centers of yuletide cheer in 1920 serve a similar purpose in 2020. One of the most popular, and most Christmassy, places in town in 1920 was a department store on Gay Street called Newcomer’s. Although run by a Jewish family, they claimed the most convincingly authentic Santa Claus. If you want to imagine Newcomer’s, go to Mast General Store, which occupies what were Newcomer’s first two floors. Today, Mast carries more toys and candy than any other place downtown.

Mast reserves the big basement room for the most outdoorsy stuff, but in 2020, it was “Toyland,” and Santa himself, the real one, reputedly, held court there.

This year, Market Square is at least modestly decked out for a holiday no one quite knows what to do with. Even without the skating rink that has been part of the holiday season for 30-odd years, it’s decorated with red bows and festive banners and multicolored tinsel and candy-cane motif of holiday lights on the trees. In 2020, the Square is mostly about restaurants. Strange as it may seem, there were only two permanent restaurants on the Square in 1920, not counting the lunch counters inside the Market House. They were called the Gold Sun and the Silver Moon. Both run by Greek families, they maintained a perhaps friendly rivalry.

Today, Market Square has many restaurants but only four retail shops, by my count. In 1920, it was the address of about 40 retail establishments, shops selling shoes, drugs, groceries, candy, not counting the big Market House itself, where there were regularly 36 additional food vendors. And in 1920, Market Square was generally where people got their Christmas trees and wreaths.

The south end of the Square was where the city put up the Municipal Christmas Tree, a green giant found out in the country. It had been erected and “wired” with 500-600 electric lights of multiple colors, with prosperous inventor Weston Fulton in charge of the decorations.

In those days the city didn’t turn it on until Christmas Eve. In 1920, it would have been weird to see a Christmas tree as early as Dec. 23. After all, it’s called a “Christmas tree.”

But that year, they had something new for the lighting ceremony. For the first time, the city would be giving holiday gift packages to poor children—1,200 of them at once. Each gift package included a half-pound of candy, a pack of chewing gum, a half-pound of nuts, an orange, and apple, and a toy.

***

At the end of 1920, the nation was waiting for President Wilson, the ailing Democratic lame duck, to yield the White House to his successor, Warren Harding, the Republican dark horse. The two presented a dramatic contrast, but neither of them would have much to say about the future. Both of them—the old president and the new one–would be dead within three years.

That December came the announcement that Harding was expected to nominate one Democrat to the Supreme Court: Knoxville’s own Sen. John K. Shields. It didn’t happen. However, Harding later nominated another Knoxvillian to the high bench, E.T. Sanford.

Harding, who had come to Knoxville during his campaign, was invited back just after the holidays, for the big convention announcing the cross-country Lee Highway. Along with the Dixie Highway, already in progress, those two national routes were cause for much excitement in Knoxville, where they met and joined each other for about 20 miles.

Don’t ever assume folks got along better back then. The season brought fierce and bitter politics, even at the local level. On Dec. 21, the winter solstice, hundreds of disgruntled citizens attended a “mass meeting” to depose the recently elected mayor, E.W. Neal, as well as the whole City Commission, a staff of experts who stood in for the old Board of Aldermen. The movement, led in part by trade-union working people, described specific charges against Neal, who was known to play favorites–but they also distrusted the whole new “progressive” form of government, which struck some as elitist. The movement failed. Neal and his staff would finish their term, but the Commission system’s days were numbered.

Knoxville was racially segregated, and becoming more strictly so than it had been in previous generations. Black people could shop in most downtown shops, alongside whites—they just couldn’t sit together in a restaurant of a movie theater or a streetcar.

That December, Judge Xen Hicks was tapped to preside over the murder trial of Maurice Mays, the African American accused on vague evidence of killing a woman in her bedroom the year before; his arrest had set off a deadly riot.

And immigrants, who had been welcomed in Knoxville in the previous century—often elected alderman, occasionally even elected mayor—were in 1920 subject of suspicion, in an era of global politics, of communism and anarchism and the fear of terrorism.

Just before Christmas, the Knoxville Journal ran an unsigned editorial—probably written by elderly Union veteran William Rule, about an anxiety of the day. “One of the besetting sins of the time in which we live is that of intolerance. It is a sin calculated to create castes in society, and in a democracy there is no place for such a thing as caste.”

***

Of course, there were no bars or liquor stores, unless you count speakeasies and bootleggers. The national prohibition amendment had passed the year before, essentially banning alcoholic beverages. Knoxville had already been dry for 12 years before that. In the month before Christmas, authorities broke up a total of 775 stills in Tennessee and four other Southern Appalachian states. Liquor was still flowing in Knoxville, though. On Christmas Eve, 19 men were arrested here for drunkenness and other alcohol-related infractions.

That year, by the way, there was a faddish term for alcoholic beverages, especially moonshine whiskey: “glookum.” Newspaper searches suggested the term was in currency only in Knoxville, and only in the early ’20s.

People may have willfully forgotten the flu. It peaked two years earlier, when it ran up a death toll of over 200 in Knoxville alone. By some accounts it was still afoot in 1920, suspected of causing some severe cases, but it wasn’t talked about much. People remembered the war better. That Christmas season, a few bodies of East Tennessee servicemen were still coming home, some of them exhumed after a hasty battlefield burial.

Those who survived, not quite whole, still occupied beds in Knoxville hospitals, two years after the war, especially the old Riverside Hospital on the east side of downtown, but there were at least three African American veterans at Knoxville General. Eleven soldiers, “mens whose minds broke down,” were at the Eastern State Asylum on Lyons View.

A Christmas Cheer Fund for Injured Soldiers drew contributions.

***

A few hundred affluent people had purchased automobiles, especially Mr. Ford’s affordable Model T. But now there were longer, sleeker, faster, more expensive models, Lincolns and LaFayettes and Pierce-Arrows and Stutz Bearcats. Motoring had been mainly a male sport until then, but by 1920, affluent husbands were buying them as Christmas gifts for their affluent wives.

Only geeky hobbyists had radios, most of them homemade. There were no radio stations to listen to, but people knew they were coming.

And football was becoming a bigger deal than it ever was before. The Vols had enjoyed a winning season under the leadership of Nebraska-born Coach John Bender. The nine-game 1920 season included games against University of Chattanooga, Maryville College, Transylvania, and Emory & Henry. The last game 1920 was on Thanksgiving, a victory over Kentucky at Wait Field. It was probably the last football game ever played at the Vols’ rocky, slopey non-regulation gridiron. A much better, and flatter, and more legal field a few hundred yards south, to be known as Shields-Watkins Field, was being readied for the next season.

It says something about the evolution of Volmania that in 1920, fans cared enough to be angry about the quality of opponents in the following year’s season. The announcement of the schedule caused “widespread indignation in the ranks of fans and alumni.” Protesters claimed the Vols would be playing only three real contenders that year: Sewanee, Vanderbilt, and Kentucky. The rest, including Chattanooga and Maryville, “are of the class that are usually booked for practice games.” Most annoying was the inclusion of a team from the Deep South: “Florida has never been more than a third-rater.” (Officials apparently tried to patch it up a bit, with the addition of legitimate teams like Dartmouth, who beat the Vols 14-3; the boys in orange did hold their noses long enough to beat Florida in 1921, but only 9-0, hardly a blowout.)

***

One of the excitements of the Christmas season was always the plenitude of citrus fruit, especially the hometown favorite, Caswell’s Grapefruit. William Caswell, the sometime developer who donated the land that became Caswell Park—which was evolving into Knoxville’s main baseball field—also owned grapefruit plantations in Florida, and was so proud of his product he put his name on it. You could buy Caswell Grapefruit at T.E. Burns’ big double-arched building at the north end of Market Square.

In the past, Knoxville shoppers often procrastinated until the morning of the 25th to finish their shopping, and in the past dozens of stores remained open until noon on Christmas to catch the business. Several stores, including Burns’, warned us that they were going to close all day on Christmas.

The YWCA offered a gift shop, and that Christmas season they were offering “Italian Art Novelties,” including fine sculpture in ivory and copies of artistic masterpieces.

Woodruff’s had started out as a hardware store and evolved into a furniture store, but carried a lot of stuff people got excited about. Daisy air rifles were already on the market in 1920, going for as little as $1.50. Iver Johnson bicycles were a premium item, mainly for rich kids, at $60.

Phonographs had been around for a long time, but there had never been more interest in popular music than there was in 1920, when some jazz singers were making records—and portable record players were new. Made to fold like a suitcase, they were going for $26-40.

Phonographs had been around for a long time, but there had never been more interest in popular music than there was in 1920, when some jazz singers were making records—and portable record players were new. Made to fold like a suitcase, they were going for $26-40.

As always, there was a problem with shoplifting, but this year, store managers remarked, brought an especially disquieting new breed of menace: “Most of the shoplifters are pretty young girls.” Clerks complained that they used their beauty to distract the clerks, often with deadly effect.

***

Movies were popular with several dedicated movie houses, like the Queen, the Strand, and the brand-new Riviera, “the Shrine of the Silent Art,” where you could watch To Please One Woman, by pioneering female director Lois Weber. The movies played all day every day, including Christmas.

Live vaudeville was still popular, though, at three or four theaters. Half-century-old Staub’s Opera House, rebranded as Loew’s Theatre, offered a three-night vaudeville show from Dec. 23 to Christmas Day, including Everett’s Monkey Circus.

Just before Christmas, the Bijou was running a live show called The Beginning of the World that was something to behold. In the first scene, set at the bottom of the ocean, “an enormous oyster opens, vomiting forth fire.” It was, according to a reviewer, “the most beautiful and delightful novelty of its kind ever produced at the Bijou.”

On the same bill was one Chief Little Elk, an eloquent Native American orator who was said to be a challenge to “the old idea that an Indian is savage.”

The following show, which covered Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, featured a bill including the singing, dancing Ezuilli Brothers, the Prince Ilma Arabian Four (“in their native costumes”) and “The Ragged Edge: a Jazz Comedy Sketch.”

Thespians aren’t called troupers for nothing—it was typical for show people to work through the holidays, and sometimes a bit harder than usual. E.A. Booth, manager of the Bijou, did something special in their honor. After the last member of the audience had left the last performance of the day, Booth hosted an informal banquet and dance for all the people involved in running the Bijou, from the office staff and ticket takers to the backstage prop guys and curtain hoisters to the actors and singers themselves were suddenly the guests for a holiday gala.

“As if by magic, when the exit march had been played, and the last person had filed out, a table reaching from one end of the stage to the other was placed, and busy waiters soon had everything ready for the host’s cheery announcement, ‘Let’s begin!’”

The banquet included turkey and cranberry sauce, and impromptu speeches and informal dancing to the house band. It went almost until the dawn of Christmas Day.

Perhaps inspired by the example of Adolph Ochs, the former Knoxvillian whose big New Year’s parties on Times Square had proven such a success, a couple of establishments hosted late-night parties. The new Farragut Hotel hosted a New Year’s Eve Dinner Dance that oddly started in the morning, at 9 a.m., and lasted 12 hours. Whittle Springs, then the glamorous new countryside hotel on the northeast side of town, hosted a gala New Year’s Eve dance, too.

The Bijou tried something new for New Year’s Eve. Dec. 31, presented a full day of five vaudeville performances in a row, each featuring four acts, including Horace Wright and Rene Dietrich, “the Somewhat Different Singers.”

Well-dressed couples stayed behind, as others arrived, for a new event called “the Midnight Frolic.” A 12-piece band played favorites as opened the doors at 11 p.m. for dancers to “enjoy the privilege of dancing on the stage, in the corridors, and in the lobbies of the theater. Confetti will be provided, and the real carnival spirit will reign.” There were noisemakers, streamers, and red and green filters for all the stage lights, making the big room almost eerily festive.

There was no announced closing time for the party, but the Bijou made arrangements with the streetcar company for a post-midnight pickup. One way or another, woozy crowds loaded with glookum found their way home, wondering what this new year, and this crazy new decade, would bring.

by Jack Neely, December 10, 2020