The Photographic Conservationist

James Edward Thompson (1880-1976)

When it comes to Knoxville photographers, James E. (Jim) Thompson was one of the most famous and most prolific – the quantity a quality of photographs that he captured on film of places and events around the city is distinctly remarkable.

His artistic talents and keen business sense worked together right from the outset of the 20th century. His company, Thomson Photo, Inc., and its related enterprises flourished for decades and is still in operation just west of downtown continuing more than a century of services for Knoxville photographers.

Thompson’s photographs of the Smoky Mountains featured in national newspapers and publications and helped booster a movement to create a national park just beyond his hometown. More than a few of his photographs are considered iconic. Outside of photography, he worked to build trails and determine lasting place names that still inform visitors’ experiences in the Smokies today.

James Edward Thompson was born on September 25, 1880 in Morristown to Charles Mortimer Thompson and Cora Hattie Stearns. Each of his parents led sufficiently interesting lives that deserve individual biographies of their own.

Charles Mortimer Thompson (1858-1939), born in Morristown just before the Civil War in 1858, lived in Knoxville as a young man and studied in the studio of professional artist Lloyd Branson. He enjoyed writing and music, playing bass horn in a brass band and serving as band leader, notably in Nashville at the state of Tennessee’s centennial in 1896.

Mortimer trained initially as a draftsman with a special focus on “perspective,” and did well for himself in business through a fruitful connection with an architectural firm in Atlanta. He also worked for a spell as an interior decorator.

In 1910, Mayor Samuel Heiskell appointed him building inspector for the City of Knoxville. There he helped produce the City’s first building ordnances. Continuing his artistic endeavors, he continued to paint; several of his paintings of city mayors, including Mayor John McMillan Brooks (1908-1909) and John E. McMillan (1915-1919) still hang in the City-County Building’s Mayoral Portrait Gallery on the fifth floor.

After 22 years with the City, Mortimer retired in 1932 and dedicated his time to developing a model home on Arrowhead Trail on the western fringe of Sequoyah Hills while cultivating flowers and studying nature. He died at the age of 82, his obituary describing him as an “artist, musician, nature lover, and philosopher.”

Jim’s mother, Cora Hattie Stearns (1857-1945), originally from New Jersey, became known, during the late 1890s, as “Mother Thompson” for her charitable community work serving destitute and vulnerable women in the city’s slums. In 1911, she was hired by the City Board of Public Works to serve as Matron of the Police force, a position originally championed by activist Lizzie Crozier French.

Serving directly under the Chief of Police, she worked tirelessly without pay for the first two years due to funding issues. In her own words she “looked after the unfortunates that fall into the hands of the police.” According to the Knoxville Sentinel, “Mother Thompson” worked night and day “in order that she might serve the city and the poor and unfortunate more readily.”

During her time as Matron, she developed a formidable reputation as for saving women in dire circumstances, often involving prostitution, and helping them rebuild better lives. One of her achievements was building a modest workhouse for girls in Maloneyville near Corryton in east Knox County. She remarked, “It was a not a palace, but they claimed they saved 16 souls the first year.” Mother Thompson died in 1945 at age 88.

The Thompson family moved to the rapidly growing industrial city of Knoxville when Jim was almost two years old. The first place they lived was a curious spot on East Hill Avenue, a rough old frame house, then a private residence owned by the family of former Knoxville Mayor Samuel Beckett Boyd (Mayor, 1847 – 1851) decades before it became known as historic Blount Mansion, saved from the wrecking ball by Mary Boyce Temple and others in the 1920s.

At an impressionably young age, Mortimer Thompson exposed his son to photography and art while using glass photographic plates to project images onto walls or canvases in the painting and decorating business. Leaving school at an early age, Jim worked several jobs including a short stint in Chattanooga. He began to take a stronger interest in photography, often experimenting with exposing film at home in a makeshift darkroom. He likely had little idea that the medium would inform a lifelong career – indeed a career that many might argue would help elevate photography to the level of an art form. But his creative side was balanced by a practical nature. He was a self-claimed “orderly man” of strict habits. In time he would build a huge collection of tools which he kept neatly in place, ready for any project. He regarded himself as a competent carpenter and could repair most anything.

When he was 17, a pivotal event in 1897 focused his life trajectory. A fire began on the 400 block of Gay Street and quickly engulfed the buildings between Commerce and Union Avenue. As the inferno raged on it became quickly apparent to the City Fire Department that it was ill-equipped to deal with a fire of such magnitude, and the Chattanooga Fire Department responded to an official distress call. Fire engines, loaded onto railway cars in Chattanooga, went up to Knoxville to help contain and extinguish the blaze. When the dust settled, the cumulative cost to Gay Street business owners led to the event being dubbed the “Million Dollar Fire.” In reality, the total cost was far greater than that.

In those days the daily newspapers were just beginning to include photographs in news coverage and had yet to employ in-house photographers. Freelance photographers were needed to capture important images and Jim Thompson, known a budding photographer, was called upon to help document the rapidly developing story of that fire. It was an auspicious event to propel his photographic career.

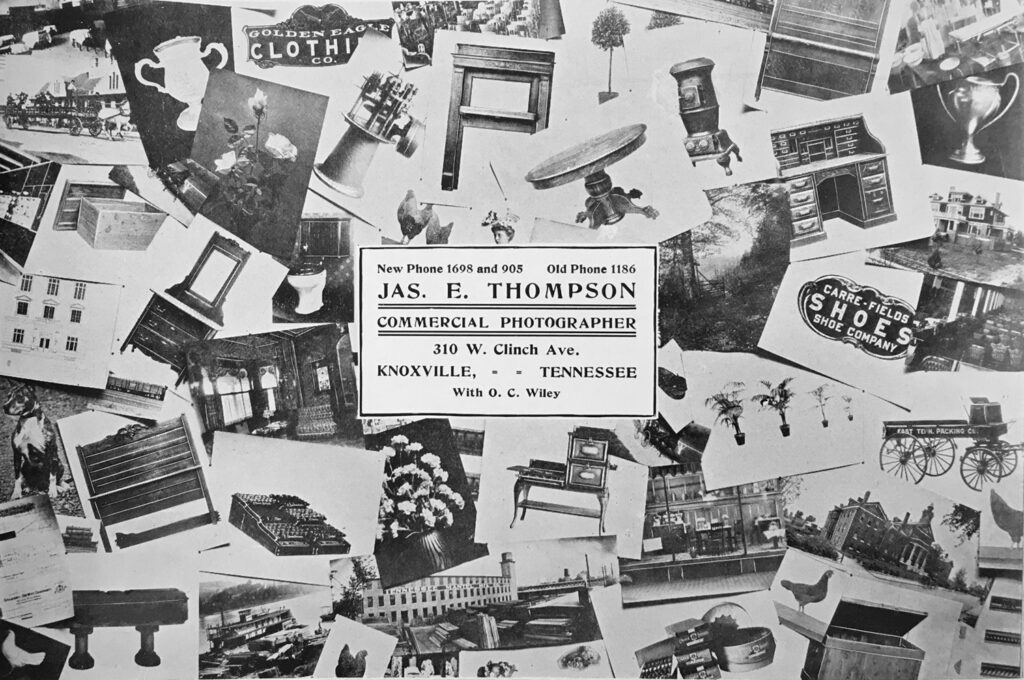

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Thompson gained employment as a contract painter and then became a technician for O.C. Wiley, a manufacturing optician and dealer in optical goods and photographic supplies, later renowned as one of the first commercial photographers in the south. Thompson rose through the ranks, enhancing his technical skills as he went. Coupled with a creative eye and an abundance of patience, he developed into a gifted photographer, and ultimately became head of Wiley’s picture department. Thompson would also train for a time to become a draftsman for renowned architect George Barber, but photography was his future.

Jim married a local girl, Emily Boyd (originally from Connecticut, her family moved to Knoxville when she was very young), in 1902. The couple married at the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church on Summit Hill and had three children, Emily and Margaret, and Charles Ethelbert (known as Bert, he would follow in his father’s footsteps in the family business).

In 1903, Thompson photographed Cowan Rodgers, an all-round sportsman and college grad-turned-inventor, who had built several prototype automobiles of his own design while working for a local bicycle company, Biddle Manufacturing Company. Thompson captured Rodgers on film as he was about to attempt to drive his latest model to Chattanooga, an unprecedented journey of 123.5 miles. It took Rodgers and his crew almost 10 hours to make it to their destination, but it was a remarkable achievement, and the photograph a milestone of local inventiveness.

With only a few commercial photographers operating across the South at that time, Thompson established himself as a pioneer in commercial photography. Early clients included the C.B. Atkin Company, for which he photographed fireplaces and produced photographs of marble displays for the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. That same year, he was called upon again to capture the aftermath of another tragedy.

On September 24, 1904 two trains, one that had just left Knoxville’s Southern Station, collided with another west-bound train headed towards Knoxville near New Market. The death toll and carnage is still regarded as one of the worst disasters in the region’s history. Thompson was called upon again by the local press to go to the site of the accident and document the horror. When he arrived, it proved a thoroughly gruesome scene, and the crash would claim the lives of more than 60 passengers, a third of whom came from Knoxville. Many more passengers and crew were injured, the wounded arriving in Knoxville late into the night on another train. The victims were taken to nearby Knoxville General Hospital. Several of those who died are buried in Old Gray Cemetery.

Thompson’s photographs of the New Market Train Wreck were displayed in a Gay Street shop window and helped further expose his work to the public at large, which not only further developed his reputation as a fine photographer, but also helped to grow his business and meet the ever-growing demand for visual documents of Knoxville life.

Thompson later said that “he could see the future demand for photography increasing” and in 1902 started his own business, Thompson Photo, Inc., in the basement of his home on Temperance Street, just east of downtown. Continued work from photographing fireplace mantels for Atkin led Thompson to acquire a new property near his home on Temperance Street, fitting the space with state-of-the-art equipment and an impressive camera room. There he could produce photographic murals up to 30 feet wide. At its peak, the firm would employ as many as 30 workers engaged in commercial photography.

Thompson also anticipated a future where he described a need “for a new style of photography in the thriving industrial center.” Between the years 1900 and 1905 Knoxville experienced a 100% growth in manufacturing, collectively offering more than 300 commercial products to various markets. Salesmen were increasingly relying on illustrated catalogues to showcase their products to customers. By 1907, Knoxville merchants were mailing between 40,000 and 50,000 mailers to their regional clients. And all those products needed illustrating and photographing. Jim Thompson was not only at the right place and the right time, but he also sensed a new opportunity to grow his business.

In those days some elements of photography were still relatively primitive compared to modern standards. Photograph paper was only available in a standard grade, and before flash bulbs emerged on the market, flash powder was used. “Most people were afraid of it,” said Thompson once talking about some of his clients’ reactions to the exploding powder. One customer asked him to photograph their Brown Leghorn chickens but was disappointed with Thompson’s results. Needing to photograph the chickens at night when apparently they were more likely to stick together, the flash powder startled them and gave them a blank look. The owner was not pleased. Chickens may have been one of the few photographic subjects that thwarted him.

Using flash powder also caused Thompson a problem at the opening of the Bijou Theatre in 1909. The assembled audience had been forewarned of the flash and handled it well, but an exploded shard of metal injured Thompson and the stagehands quickly lowered the curtain again to avoid the crowd seeing blood run down his face. The resultant photograph proved to be distinct enough that it is still used today.

Four years later, Thompson served as an official photographer for the National Conversation Exposition held at Chilhowee Park in 1913. Attracting over one million visitors in its two-month run, the Exposition might be regarded as one of the best documented cultural events in the city’s history. Many of the remarkable photographs of the buildings, exhibits, and the crowds were, of course, Thompson’s. Although he tended to prefer shooting “things” rather than people, he enjoyed meeting and photographing Williams Jennings Bryan, then Secretary of State. That image, however, has not survived.

As his business grew, he went on to document many other aspects of Knoxville life. One shot proved quite challenging –the impressive soda fountains at Kuhlman’s on Gay Street. Thompson was embarrassed by how long the shot took to capture. Interviewed in 1970, he recalled,

“We didn’t have wide-angle back then. I had to back out in the street and block off the entrance to keep people from moving in and out. No fast speed settings, either. Had to set up my tripod and put flash powder in a pan I held over my head and when I pulled a trigger and send a little alcohol flame into the powder it would BOOM! Of course, crowds gathered. Later, I didn’t mind the crowds. It was good for business. But then I was shy and easily embarrassed.” (Knoxville Journal)

Thompson Photo Inc.’s bread-and- butter commercial jobs in the 1910s and early 1920s included photographing progress on construction projects, helping investors verify work was being carried out correctly. Photographers were required to set up in exactly the same location every time so that accurate progress reports could be made. Likewise, photographs of accident sites where a member of the public was injured and subsequently sued a business owner or the City required careful accuracy and consistency.

In 1919, Thompson would photograph a milestone in downtown infrastructure improvements – the raising of the 100 block of Gay Street to flatten the roller coaster dip in the road and rebuild the viaduct over the railroad. Now over a century later, the two ramps connecting Jackson Avenue to that viaduct are undergoing extensive repair.

That same year, Jim’s younger brother Robin joined him in business to form Thompson Brothers. During the World War, Robin had been stationed at Quartermaster Corps at Camp Sevier in South Carolina before being transferred to the United States School of Aerial Photography at Rochester, New York where he trained for six months. On his return to Knoxville he partnered with his brother for several years before branching out with his own company, Robin Thompson, Inc. in the mid-1920s. The brothers had a sometimes-challenging relationship, with Robin’s gentle nature in sharp contrast to Jim’s sometimes overbearing persona (family members have commented on how Jim could be far warmer with his business customers than he was at home).

By 1929, Robin established himself in the Daylight Building on Union Avenue, noted for its natural light and use of large plate-glass windows and skylights. Robin specialized in aerial photography utilizing a camera fastened underneath the wing of an airplane and operated using a lever.

Around the same time, Jim Thompson opened the Snap Shop, a film processing and retail camera store, in a retail space shared with Crouch Florists, on W. Church Avenue managed by his son, Bert. In the early ‘30s the business moved to the 600 block of Gay Street with expanded offerings, including a home movie screening room on a mezzanine in the back of the building, and a dedicated sales room for Kodak cameras and photo supplies.

But there were notable photographs prominently displayed in these businesses that would be considered the pinnacle of Thompson’s professional achievements. They were his remarkable photographs of the Great Smoky Mountains.

***

Jim Thompson’s love affair with the remote mountains beyond Knoxville, which many in the early 1900s regarded as a wild and forbidding place, began in 1913 or 1915 (sources differ). Back then, before good roads, it often took two days to travel there. On those early expeditions Thompson particularly enjoyed photographing wildflowers. But it wasn’t until a decade later that his photographs, now constituting an increasingly impressive portfolio, featuring stunning photographs and panoramic shots of the mountain peaks, natural formations, and streams, that his artistry was called upon to help a higher cause, the idea for a national park.

Throughout his life, Jim would tell the story many times and no doubt some parts of it have become embellished or enhanced a little by its own legend. But late in life, Thompson reminisced once more about the day that Colonel David Chapman, the formidable leader of the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association, asked him to help influence the chances of the Smokies becoming a national park by taking his photographs to a special meeting in Asheville, North Carolina during the summer of 1924.

Col. Chapman instructed Thompson, official photographer for the association, to place as many of his best framed Smokies photographs in the back of his car as he could. He was then to drive them to Asheville’s famous Grove Park Inn where the Southern Appalachian National Park Commission was convening to evaluate potential sites for the location of a new national park in the eastern United States (following Acadia National Park in Maine, created in 1919). In addition to the Great Smoky Mountains, top contenders were Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina and part of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

Thompson recalled in numerous newspaper interviews over the years that when members of the Park Commission arrived at the hotel they were very high on the merits of Grandfather Mountain – they had just returned from a visit – but they were immediately astounded by his photographs of the Smokies. In fact, the Commission members were so impressed by them that they began to wonder if they were too good to be true and so wanted to see those places for themselves.

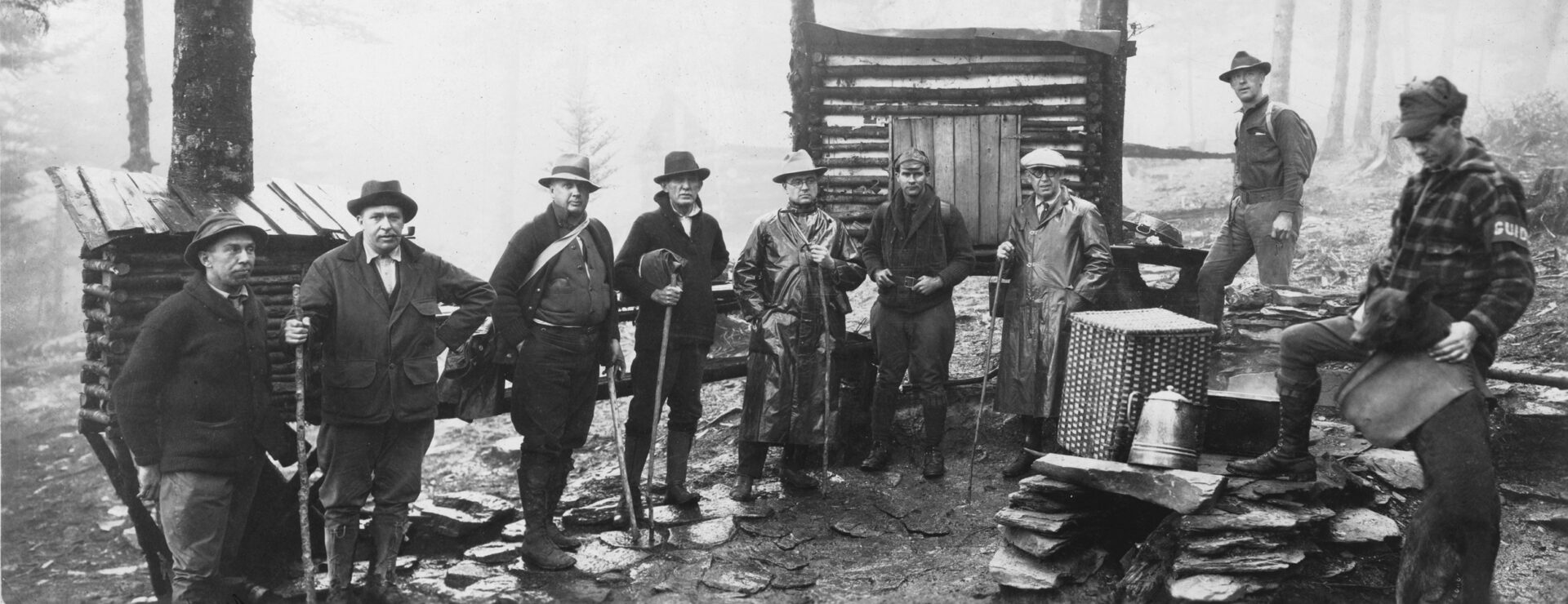

A week later, the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association organized a guided trip for several Commission members to the Tennessee side of the Smokies, which first met at the Mountain View Inn in Gatlinburg. Col. Chapman served as ringleader for the expedition, assisted by Paul J. Adams, a relatively young newcomer to Knoxville who helped with logistics and as a trail guide. (A year later, Adams would be hired by Chapman to develop the first campsite on Mt. Le Conte, now the site of the popular Mt. LeConte Lodge.) It took planning to fully explore the Smokies, at a time before proper trails existed, especially on Mt. Le Conte for the Commission to see the actual scenes that had been photographed. The trek was a remarkable success as members of the Commission could readily see that Thompson’s evocative photographs were indeed genuine. This was a pivotal turning point in the bid for the Smokies to become a national park – although a long battle remained involving many players to help acquire thousands of separate parcels of land before the park became a reality.

***

During the 1920s, Thompson’s superlative photographs of the Smokies began to appear in national newspapers and magazines. In 1926, Horace Kephart (1862-1931) chose Thompson’s photographs to illustrate a new article, “The Last of the Eastern Wilderness” for World’s Work magazine. Kephart, an Harvard-educated man, had abandoned his career as a librarian, as well as his family, due, among other factors, to extreme stress and unexplainable mental anguish leading to a planned suicide attempt. In 1904, after he had partially recovered, he purposely chose the Smoky Mountains for its remoteness as a place to rebuild his life by adopting the old Pioneer ways of life and to re-focus on writing. Kephart often lived in seclusion while keenly observing the mountain folk’s ways and customs and becoming a formidable woodsman. His books, Camping and Woodcraft (1906) and Our Southern Highlanders (1913), have become classics.

Thompson would later work with Kephart on developing the segment of the Appalachian Trail through the Smokies led by Paul Fink, a banker from Jonesboro and an early Smokies authority. Divided into five districts, the Appalachian Trail Conference appointed three members to each district. In the Smokies section, Fink, Thompson, and Kephart were charged with “establishing a traversable route and energizing the local hiking clubs.” Thompson and Fink’s knowledge of the history and terrain on the Tennessee side complimented Kephart’s detailed understanding of the North Carolina side. Assisting Kephart was a hardworking auxiliary member, another gifted photographer who would rival Thompson’s expertise in capturing the splendor of the mountains, George Masa (1881-1933).

About the same age as Thompson, Masa was born in Japan and had immigrated to the United States around 1915, arriving in San Francisco before heading east, landing in Asheville. Although he initially worked as a laundry man at the Grove Park Inn (where Thompson’s own photographs would make such an impact a decade later), Masa possessed a similar entrepreneurial spirit as Thompson and yearned to make his mark as a photographer and own his own business. Although he would never be as successful as Thompson in commerce, Masa nevertheless began publishing his photographs of the Smokies by the mid-1920s, bringing his name to the attention of Horace Kephart. In time, Kephart and Masa discovered they shared a common passion for the rugged wilderness and the need for preservation. The two developed a close friendship, often exploring the Smokies together, and working in their own ways in North Carolina to promote the national park alongside efforts across the state line in Tennessee. According to historian William A. Hart, Jr., Thompson and Masa were known to correspond warmly over committee matters and most likely met while working on parallel efforts to establish the Appalachian Trail. It is of little doubt they would have appreciated each other’s photography skills.

Thompson also worked with Paul Fink on the five-member Smoky Mountains Nomenclature Committee in 1929. The U.S. Geological Survey, under Col. David Chapman, charged them with “deciding the official names of the mountains, passes, streams, and other points in the Smokies” to eliminate duplication of names. In addition to Thompson and Fink, other members included Hodge Mathes (a park enthusiast from Johnson City), and two others from Knoxville: Robert Lindsay Mason (Knoxville artist and author of The Lure of the Great Smokies, 1927), and Brockway Crouch (florist and veteran naturalist). The work of the Nomenclature Committee again brought Thompson into contact with Kephart who served on the corresponding North Carolina committee, with Masa again serving in an unofficial capacity. A recent book, Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography by George Ellison and Janet McCue (Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2019) highlights how instrumental Thompson was in the nomenclature committee’s success and reveals deeper connections with Kephart and Masa. In a letter to Arno Cammerer, then associate director of the National Park Service, referencing the group’s accomplishments, Fink praised Thompson for his dedication and hard work:

“Now that preliminary sheets have been issued for most of the map of the Smoky Park, we are striving to bring our nomenclature work to a head. Jim Thompson has done a monumental piece of work in transcribing every place name in the park area, arranging them alphabetically, with location, so that we can decide on elimination of duplications, unsuitable names, and the like.” (Nov. 26, 1931)

In 1931, the two committees would be shocked to hear of Horace Kephart’s tragic death in a car accident near Bryson City. Masa organized a commemorative hike to the peak now named Mt. Kephart in the Smokies on April 2, 1933 to mark the second anniversary of Kephart’s death. A hundred or so hikers joined the proceedings to remember their old friend. Jim Thompson, by then familiar enough with Masa to share warm correspondences over committee activities, was one of the hikers.

Barely two months later, George Masa died after recurring bouts of ill health. The legacies of Kephart, and particularly Masa, have enjoyed a new appreciation following their poignant portrayal in filmmaker Ken Burns’ series The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009). Unfortunately, the efforts that key players from Knoxville and other parts of Tennessee contributed to the movement to establish the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were barely mentioned in the series’ narrative, and Jim Thompson’s artistry and contributions were completely ignored. As a result, Thompson’s artistry still warrants proper recognition on the national stage.

***

How did Jim Thompson physically capture the grandeur of the Smokies? In addition to his experience and innate sense of composition, it also took him, and many helpers, a lot of patience and hard work.

Thompson’s typical photographic equipment included a heavy Eastman view camera with bellows and a hood, along with eight by ten inch or five by seven inch glass or film negatives, up to 50 negative holders, plus a wooden tripod. The whole lot weighed in excess of 75 pounds and required help from Carlos Campbell, Brockway Crouch, and other members of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club to carry the equipment up and down the sides of mountains and through valleys. They dubbed themselves Thompson’s “porters” and sometimes held tree limbs back to aid a picture. Thompson was meticulous with the way he approached a shot, and often tested the patience and stamina of his helpers as he waited, sometimes for hours, to capture the perfect shot in the perfect light. The photographic results often proved worth the wait.

Also requiring a steady hand was Thompson’s Cirkut #10 panoramic camera, which incorporated a special geared tripod mount that allowed the cameraman to rotate the camera 360 degrees to achieve spectacular results when the camera was fully level. He used this set up to great effect with scenes of assembled church groups, college students, military camps, as well as local quarries, industrial plants, and the Smoky Mountains.

As a charter member President of the Smoky Mountain Hiking Club (formed in 1924), Thompson took a staggering number of photographs on hiking trips. He also supplemented those expeditions with special treks just to capture specific scenes like the one that ended up as a full-page illustration in a 1936 edition of National Geographic. Many of his photographs, including Charlie’s Bunion, the Chimney’s and Alum Cave have become iconic images of that era, not only of the Smokies, but also of those heady days when the movement to create a park in the mountains were both a thrilling and formidable dream.

In the coming years, Thompson’s images would be centrally featured in publications ranging from park booster works such as “The Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Land of the Everlasting Hills” (1928) to Knoxville author Laura Thornburgh’s renowned narrative-driven cultural guide, The Great Smoky Mountains (1937). The latter publication remained in print for decades. However, Thompson claimed he didn’t get rich from his mountain photography. “I enlarged them and colored them and did different things to them to try and make a sale. Well, I never really made any money out of the mountain pictures in the long haul. But of course, I did get a lot of publicity that helped in our other photography business.” (Knoxville Journal, Nov. 10, 1977)

***

Jim Thompson may have been the most prolific Knoxville photographer of the Smokies, but there were others. Before him, Prof. Samuel H. Essary (1868-1935), a botanist and professor at the University of Tennessee’s Agriculture Station, and a respected explorer, may have been the first photographer in Knoxville to capture the Smokies in a professional manner. It is not clear if Essary and Thompson were closely connected, but several of Essary’s images were selected to enhance Kephart’s second and expanded edition of Our Southern Highlanders in 1922.

Good friend and hiking companion Albert “Dutch” Roth often accompanied Thompson on Smoky Mountains Hiking Club expeditions, taking his own photographs of the same mountain scenes using his own Kodak 122 camera. Roth was clearly inspired by Thompson’s artistry, but was more of a prodigious hiker and camper than Thompson. Roth caught a ride to the Smokies and other destinations almost every weekend, taking photographs more on the fly as compared with Thompson’s meticulously patient set-ups. Roth was also a loyal customer, taking his camera film to be developed at Thompson’s Snap Shop camera store after he knocked off work at the Coster Shop railroad factory in north Knoxville. Further, Roth supported Thompson’s efforts to develop and mark the Appalachian Trail in the Smokies. His own extensive collection of images is online, alongside Thompson’s, as part of the University of Tennessee’s digital collection, including his pictorial scrapbook, “Tales from the Woods.”

A notable helper with the Appalachian trail was also Granville Hunt, then a young assistant staff photographer for the Knoxville News Sentinel who went on to become a talented filmmaker and documentarian.

After hiking with Thompson, Carlos Campbell, another frequent hiking companion, was inspired to take his own photographs. As head of the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce and a key figure with the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association, Campbell was a vocal champion of the national park effort. His own Smoky Mountain photographs would, in time, also grace the pages of the National Geographic, and in 1960 he would go on to write and publish the detailed account of the effort, The Birth of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Carlos Campbell wrote in his book, “Mr. Thompson…was a Great Smokies enthusiast. He went into remote sections of the area and brought back pictorial evidence of the charm and majesty that was later to be enjoyed firsthand by millions of people. It requires no stretch of one’s imagination to realize that without the help of these magnificent views there might have been no national park in the Great Smokies.”

***

In 1933, Jim and Robin reunited to form Thompsons, Inc. Located in the Lowry Street studio, the set up was again dubbed “one the most complete studios in the south” where they focused on commercial and industrial photography as well as portraits for newspaper and schools. If that wasn’t enough, they also handled Kodak finishing for more than 100 regional firms and served as local moving pictures reps for Pathé News and official “camera representatives” for Fox News Weekly, both well-known newsreel companies.

It is easy to overlook the fact that Jim Thompson was also an accomplished filmmaker. The earliest surviving example of his work is a few seconds of footage showing a fire engine on Commerce Street from 1915. The recently discovered one-minute footage covering the 1919 race riot is also likely Thompson’s. The Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound, part of Knox County Public Library, has about 100 Thompson reels in its collection.

For a fee, Thompson would produce home movies for clients, either family portraits or short films where they could “see themselves in the movies”. He made films for several prominent Knoxvillians, including General Lawrence Tyson, and C.B. Atkin, who he worked for early in his career. During the 1920s, Thompson shot numerous films of his fellow members of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club exploring the natural countryside as well as some high jinks during a rest stop. Together with his landscape photography, Thompson’s films capture the spirit of the Smokies and how much he and his fellow Knoxvillians enjoyed visiting them.

Although not a natural sports fan, Jim Thompson also enjoyed photographing University of Tennessee football games from 1925 until 1962. The moving pictures were particularly appreciated by Coach Robert Neyland who had joined UT for his first stint as coach for the Vols in 1926. Neyland had experimented with studying moving pictures when he was at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Thompson would film the weekend games at Shields-Watkins Field and then midweek would set up his camera and projector for Neyland and his staff to re-watch the plays and prepare for the next game. For a long time, Thompson served as the official photographer for the UT Athletic Association.

***

Outside of business, Thompson was a dedicated member of the Knoxville Rotary Club. He and Brockway Crouch both held perfect attendance records for many years, something both men were keenly proud of. One time, following some mishap, Thompson had colleagues bring him to meeting on a stretcher rather than blot his record. In 1938, the club presented Jim with a special award for a perfect 21-year record of attendance and he ultimately went 40 years without missing a meeting.

Knoxvillians on Mt Le Conte, 1927. Florist Brockway Crouch is fourth from left; Jim Thompson is second from right, and next to him is trail guide Paul Adams with his legendary dog, Cumberland Jack (or Smoky Jack as he was known when he was in the mountains.) (University of Tennessee Libraries)

During the Word War II years, camera film was rationed causing long delays for customers to buy film. The Snap Shop weathered the era by selling reproduction prints of Jim’s Smoky Mountains photographs and expanding its product range to include non-camera items such as safety pins, pen sets, even diapers – anything to keep sales going. The store later diversified into office equipment by acting as a regional distributor for Kodak’s latest copy machines.

Staying close to his beloved Smokies, Thompson opened a photographic store in Gatlinburg in 1937 which lasted well into the 1960s before rising rent payments seriously undermined its profitability. The store sold murals and prints to tourists, and also area merchants. Hand-tinted enlargements of his photographs were ordered by hotels and displayed in lobby’s and ballrooms such as the Riverside Motor Lodge in Gatlinburg. Reflecting on his grandfather’s work, grandson James Thompson recalled that his grandfather employed “colorers” who worked long hours on jobs and it was his grandmother, Emily, who was one of the most talented. Some of the enlarged hand-tinted murals were put up in local banks.

Jim Thompson continued at the forefront of his profession and served as President for the Southeastern Photographers Association, and the National Photographers Association of America. In the early 1950s, the Photographers Association of America awarded him the title “Master of Photography.”

In 1952, Jim’s wife, Emily, died just a year after the couple celebrated their golden wedding anniversary at their Gatlinburg cottage, Shangri-La. Twelve years later, when he was 82, Jim married again, this time to Margaret Arning, a longstanding employee at his firm. The couple lived on Scenic Drive in Sequoyah Hills. His previous home and studio east of downtown on Temperance and Lowry streets were to be erased by the effects of Urban Renewal.

Snap Shop expanded beyond downtown Knoxville with a new store opening in Western Plaza in 1959, the modern shopping center on the eastern fringe of Bearden, which had opened to some fanfare the previous year. By then, Bert’s sons were involved in the family business, Ed helping with retail while his brother James specialized in commercial aspects.

Stores followed on North Peters Road in West Knoxville and further afield into Oak Ridge and across the state line for a while in Lexington and Frankfort, Kentucky. In 1968, Thompson opened the flagship store on University Avenue, later Middlebrook Pike, now managed by his great-granddaughter Ann. The last remnant of Thompson Photo still remains busy, perhaps the only brick and mortar old-style photography store left in town, unassumingly serving customers avoiding online options.

In his eighties, Jim Thompson finally retired. But prior to that, at some point in the 1960s, he sold many of his glass negatives to a Knoxville woman for $500 who in turn sold them on to entrepreneur Gene Walker who tried unsuccessfully to print enlargements and make a busines out of them. He didn’t have the right equipment like Thompson did. Walker subsequently became a welder and later moved to Puerto Rico. The whereabouts of those negatives remains a mystery.

***

In the early 1970s, encouraged by librarian Pollyanna Creekmore, then head of Lawson McGhee Library’s McClung Historical Collection, Thompson left the Knoxville community an unprecedented legacy: he donated approximately 35,0000 photographs to the collection. Many of those photographs, including the Smokies, buildings, churches, bridges, performances, and sports games not only remind us how life used to be, but also inform the stories of Knoxville’s past that are relevant today. And without Thompson’s considerable output work, far less would be known about the history of this city. In fact, it hard to look back into Knoxville’s visual past and not see the city through his eyes and his camera lens.

Thompson’s images are available to the public to view online as part of the Thompson Brothers Photograph Collection. Likewise, the University of Tennessee Library system also maintains an extensive collection of Thompson’s work in online galleries.

Following his death in 1976 at age 95, Jim Thompson was buried high up on the hill at Highland Memorial in Bearden. Before he died, he reflected with a reporter from the Knoxville Journal on his almost century-long life and career. He said he was “no historian, but had an instinct for saving pictures that are going to be valuable someday.” Anyone, but particularly historians, would surely agree.

Paul James, Knoxville History Project