The Bottom

A preliminary historical narrative of the area affected

by the proposed stadium project

By Jack Neely – May, 14 2021

Prepared for the Gem Community Development Group

Baseball Stadium Project Site (WBIR.com)

The project area that lies from Patton to Florida Streets and north of First Creek to East Jackson was mostly green and undeveloped until the arrival of the first railroads in the 1850s. The wetlands associated with the sharp bends of First Creek made it attractive to sportsmen, both for hunting and fishing. In the 19th century and into the 20th, First Creek’s crooked course took it much father to the north than it does today. It crossed the southwestern part of the project site and flowed another block to the northwest to almost touch what is now East Jackson before flowing more directly to the south.

The swamp known as the Flag Pond extended mostly to the west of this area. Mill dams created enormous ponds that covered much of the naturally drier area.

Although the low, marshy land did not suggest either residential or commercial development, except for small mills, the flatness of it made it the best site for the construction of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad in 1858.

Much of the area was flooded by Union engineers in 1863, as a defensive measure against the anticipated Confederate siege. Perhaps as a result, no assaults came from the northeast.

In anticipation of the railroad construction, the northern part of the project site was annexed into the city of Knoxville in 1852. An area just to the south, which had been the separate incorporated suburb of East Knoxville since the 1850s, was annexed in 1868. The 1859 city directory refers to Patton, Willow and Hardee Streets (then East Jackson from Florida Street to the creek) as existing in “East Knoxville.”

Around the time the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad was building tracks just to the north, another railroad, the Knoxville and Charleston, was using the western half of the project site. The railroad was never completed, though it built track in Blount County and piers for a bridge over the river at Knoxville. By the late 1860s, a large area between Central and Humes was referred to as “the abandoned Knoxville & Charleston Depot Ground.”

Map of Knoxville, 1867 (detail) showing Cripple Creek east of today’s Old City. (McClung Historical Collection.)

In March, 1867, the area was inundated by the most catastrophic flood in regional history, and it’s safe to say the entire area was several feet underwater for several days. Fortunately there was little development in terms of businesses or residents at the time.

Perhaps surprisingly, though, it was that same year the area to the west along Central supported significant industry, especially the Burr and Terry Sawmill, which manufactured architectural products like doors and windows for the booming housing market.

The streets in the project area are all remnants of old streets, all with origins before the Civil War, though they didn’t all reach this far then. Patton Street was a long, slightly crooked street that started at East Cumberland and ran north to Mabry (now Summit Hill, roughly). By the early 1880s, it had to cross First Creek to intersect with Hardee (now East Jackson).

Humes Street, which still lies on the northwest side of Jackson, originally crossed the project site vertically (north and south).

Campbell Avenue originated at Humes and extended east to First Creek. Perhaps hard to picture today, it was a significant east-west route, a much longer street than the remnant that exists today east of Florida Street. It once extended from the old Heiskell School, a public school for African American children, on the east, to the stockyards on the west.

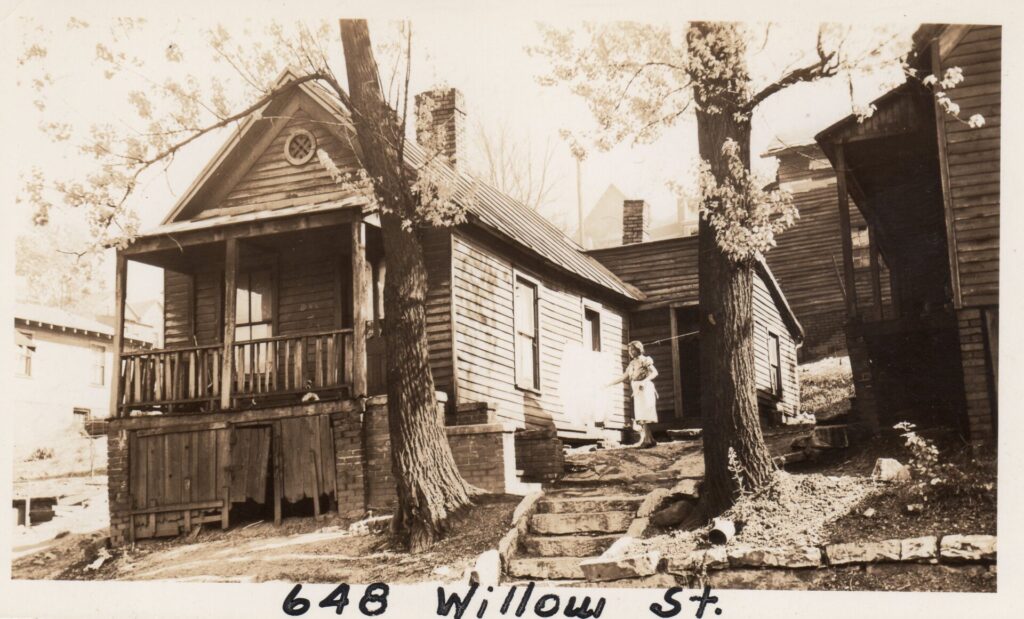

Willow Street ran very close to the banks of First Creek, which probably supported dampness-loving willows here. Maps indicate that Willow was at one time on the other side of First Creek, which has changed its course more than once over the years. Willow originally ended before reaching as far as Central, but some demolitions permitted it to intersect with Central around 1905.

Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, and Ohio Streets were obviously named on a state theme, by the 1850s. (It’s interesting that these names were avoided by the developers of state-themed Lonsdale, decades later, likely because the names already existed in the city.)

The specific name origins of Patton and Campbell are obscure, though there were people with both names living in Knoxville in the mid-19th century. Jackson Avenue is not named for Andrew Jackson, as is often assumed, but for Richard Jackson, a post-Civil War ETV&G railroad executive. Jackson was originally a very short street intersecting Gay. Hardee Street was on the east side of Central, and was originally a rather short street, too, but after an expansion of Jackson Avenue in the late 1880s, it eventually became known as East Jackson.

Some of the higher ground in the area was developed for residences of generally affluent Knoxvillians, notably the Branners, including Hardy Bryan Branner, mayor in 1880, and his mother, Magnolia, for whom Magnolia Avenue is named who lived in a large and elaborate house near the northeastern corner of the tract, near Florida and East Jackson, in the 1870s. The family had abandoned it by the early 1880s, after which it was subject to rumors and ghost stories that seem to have prompted its demolition.

A pioneer subdivision called Shieldstown, established before the Civil War, was a short distance to the east, just beyond the creek. Unusual for the era in its suburban layout, it was eventually incorporated into Knoxville’s slow expansion, leaving few traces.

The immediate area of the project site was still considered attractive enough in 1875 that it became the site of the Peabody School, Knoxville’s first public school to be built for white students. Located on Morgan Street, it operated until 1930. (The surviving building, the oldest building in the general area (older even than any building in the Old City), has been known in recent years as the AFL-CIO headquarters, and the Democratic Party’s headquarters.)

However, as noisy, smoky train traffic increased, and the trains attracted industry like packing houses, lumber and marble mills, and machine shops–and the reality of seasonal flooding became more evident–land values declined, and the bottomland became less attractive to those who could afford to live elsewhere. After 1885 or so, most of those who lived in the area were working people of modest means, especially African Americans, many of them formerly enslaved–and European immigrants, many of them refugees who arrived in town with little or nothing.

By the 1880s, it was a mixed-race area getting a reputation for cheap saloons and nightlife, and was known as part of Cripple Creek, a term applied both to the neighborhood and to First Creek itself, in reference to the stream’s sharp angles.

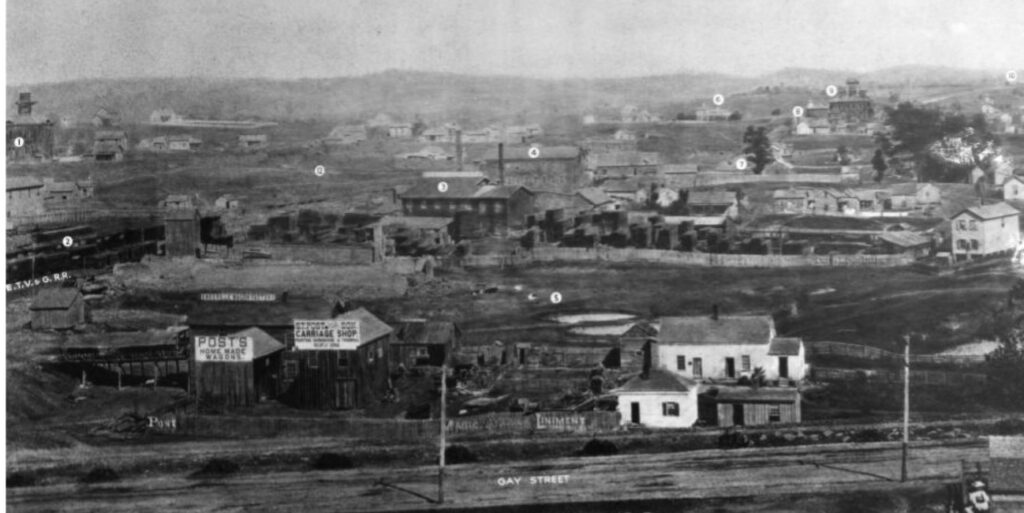

Looking east from Gay Street towards the project site. The Burr and Terry Mill is in the center of the photograph, and center right, site of the old Circus Grounds. (McClung Historical Collection.)

When Burr and Terry retired and closed their sawmill in 1887, they vacated the area around what’s now the two 100 blocks of Central, opening up the opportunity for the city to build West Jackson, which almost immediately made Hardee, soon to be renamed East Jackson, a more important street.

Chicago-based Armour opened a meatpacking facility on Hardee, a few yards northwest of the project site, in 1889. It was the first corporate industrial facility in Knoxville, and the first big meatpacking plant in this bottomland area. It was followed a few years later by another national meatpacking name, Swift, which opened a facility at 521 East Jackson. These became major employers, and became a further attraction, beyond the cheap land, for working-class people of both races to live within walking distance.

One of the most interesting and surprising businessmen to emerge in the area was Harry Royston, an African American former circus carnie who began making and selling tamales from places in the vicinity of Willow and Patton around 1887.

Before Magnolia Avenue was built, Hardee was more of a thoroughfare familiar to the city as a whole. By 1886, a mule-drawn streetcar called the Mabry, Belle Avenue & Hardee Street Railroad Co. serviced the northeastern corner of downtown, along First Creek. The streetcar line subsidized a baseball diamond touted as ideal, for a team sponsored by merchant Eli Lieber. It’s unclear exactly where it was, just that it was near the creek. It’s possible that it was near the future location of Caswell Park.

The first electric streetcar, bound for Chilhowee Park, boarded on East Jackson near the project site in 1890. (Its proprietor was young attorney William Gibbs McAdoo, who would 25 years later be U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and later still a significant presidential candidate.) It’s interesting evidence that East Jackson was not considered fatally intimidating to the general public at that time.

Despite the smell and noise of industry, Hardee Street (East Jackson) was the main office of Stephenson and Getaz, one of the city’s busiest architectural firms, noted for designing the Knox County Courthouse in 1886.

Although flood-prone, the rarity of the flat areas around First Creek made it attractive for some activities that required a couple of acres of flatness.

Circuses usually set up at one of two or three places on the east side of First Creek, like the Bell Avenue Grounds, but for a time in the 1890s, small circuses sometimes raised a tent on what was called the Florida Street Grounds. In April, 1892, the Nickel Plate Show, a circus with performing lions and tigers, set up on Florida Street near the railroad tracks. In October, 1892, Professor Gentry’s Pony and Dog Show attracted crowds there. The “Florida Street Grounds” may also be the vaguely described spot where some reckless athletes got in trouble for playing baseball on Sunday in 1893.

***

Despite those sunny moments for middle-class Knoxvillians who came there to catch a streetcar or for an afternoon diversion, it was a different story for people who were trying to live there.

First Creek remained rampant and ungovernable, flooding almost every spring, often more than once. Floods caused property damage and killed livestock, but also promoted serious waterborne diseases, including cholera in the 19th century, and typhoid into the 20th century. For whatever reason, smallpox, tuberculosis, and diphtheria outbreaks were more serious in the Cripple Creek area, too. What was probably the city’s first mandatory vaccination effort was aimed at the residents of Cripple Creek, led by a city health official known as the “Czar of Cripple Creek,” whose credibility may have suffered when he came down with smallpox, himself.

The progressive administration of Mayor Samuel Heiskell was known for supporting services for African Americans. Named in his honor was the Heiskell School, a public school for African American children constructed in 1897 at the intersection of Campbell and Kentucky.

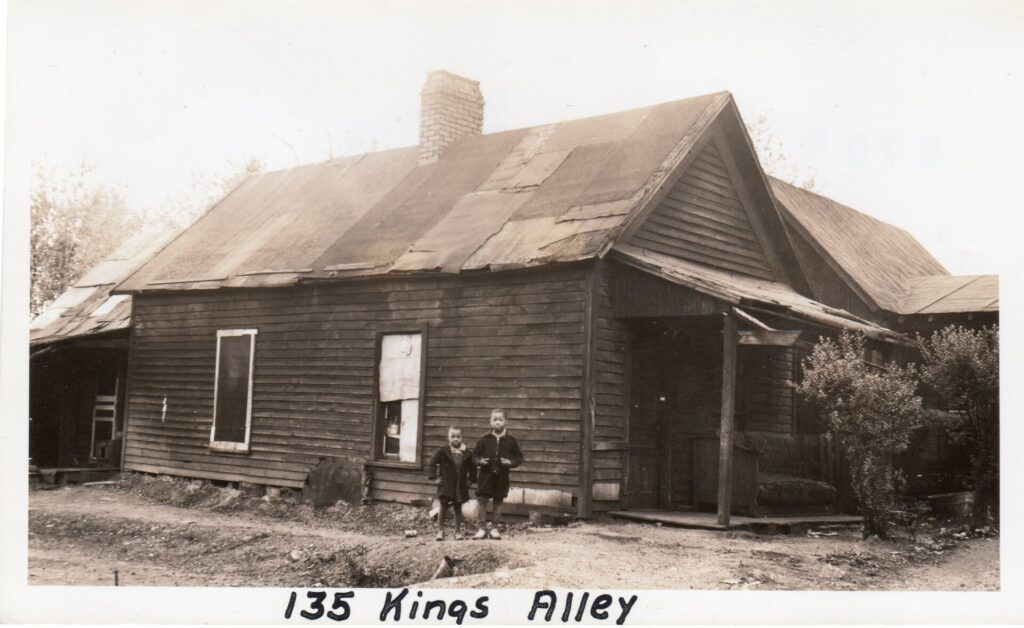

King’s Alley first appears in city directories in 1891, parallel to Patton and Florida, but between the two, extending south of Hardee, or East Jackson. It more or less bisects the project site. Like many “alleys” in predominantly poor neighborhoods, it was not a service alley but really a narrow residential street. Originally it was a mixed-race street, with five white families. Several of its households were run by single women who worked as laundresses or cooks.

By 1900 and later, King’s Alley appears to be entirely African American. Many of its residents appear to be short-term, but one exception was an African American man named Lee Starr, who was a cobbler; he remained a resident of King’s Alley for half a century.

For reasons unknown, King’s Alley became Quebec Alley around 1925, later to be Quebec Place; however, neighbor Robert Booker affirms that in his youth in the 1940s and ’50s, it was still known popularly as King’s Alley. A brass marker embossed “KINGS ALLEY” was still visible in the East Jackson sidewalk until dislodged by a city construction project around 2016. (Seeing that it was about to be thrown away, UT professor Chad Hellwinckel picked it up and put it in his Parkridge garden. He has stated that he’ll return it if there’s a worthy place for it.)

***

Law enforcement authorities and reformers alike tried to face the challenge of prostitution in the district, which was rampant by the late 19th century, and often associated with deadly disease, drug abuse, exploitation of minors, suicide, and murder. In 1900, the city during the liberal administration of Samuel Heiskell tried to establish a sort of red-light district along Florida Street called Friendly Town where prostitution would be officially tolerated, but also closely policed. Friendly Town lasted for about 15 years. Although it attracted some more affluent and law-abiding prostitutes, it was obvious that other, less intimidated prostitutes remained in some places closer to downtown where they had been ensconced for decades. Also, Friendly Town was not as orderly as hoped, as evidenced by a 1905 murder, about which prostitutes refused to cooperate with police; and in 1906, when a white man named John McPherson, visiting Florida Street with his father, killed the husband of an alleged prostitute, on a night that ended with him also killing a sheriff’s deputy. McPherson was hanged for the crime two years later, the last man ever to be hanged in Knoxville.

The prostitutes of Florida Street appear to have been mostly white, but otherwise the street was home to people of both races. In 1894, for example, 408 Florida was the home of C.M. Thompson, portrait painter, brass musician, and manager of the City Band. He was also the father of noted photographer Jim Thompson, who presumably lived with him there. (Although best known for photographing successful businesses and affluent white conservationists, Jim Thompson seems to have been comfortable in East Knoxville, where he lived for many years, and where he maintained his famous studio, near Cal Johnson’s park.)

It may be interesting to note that Florida Street was also at least for a couple of years the childhood home of Grace Moore (1898-1947), the future opera and movie star, when she was a very young girl. That fact is evident in both city directories and the 1900 census, though in her autobiography, she chose not to remember her Knoxville years when her family lived between a sausage plant and a red-light district. With that excision, she also shaved a few years off her public age. Her family may have felt relieved to move to small-town Jellico around 1905. (They lived near Magnolia, on the part of Florida Street later renamed Randolph, perhaps to distance its residents from the stigma of the red-light district.)

In 1912, Methodist minister Henry Spencer Booth took a guided tour of Knoxville’s whorehouses, and wrote an essay he called “A Trip Through Knoxville’s Foreign Mission Quarters,” the title meant as a slap to local churches who were more interested in helping third-world peoples than those in their own city, whose conditions were no better, and often worse—where people without lights or plumbing lived among “cocaine joints” and garbage heaps, at the mercy of a dirty and unpredictable creek.

However, he noted that the city’s finest brothels were those of “that aristocratic section of slumdom known as the red-light district on Florida Street,” where he witnessed expensive furnishings, imported art, and “an air of considerable decency.” After 12 years, though, Friendly Town had not reduced the prevalence of more severe conditions of prostitution a few blocks away on Central.

The city eventually gave up on the Friendly Town experiment around 1915, near the end of the Heiskell era.

Prostitution became less concentrated after 1915–thanks partly to the banning of saloons after 1907, and partly to the suburbanization enabled by the automobile.

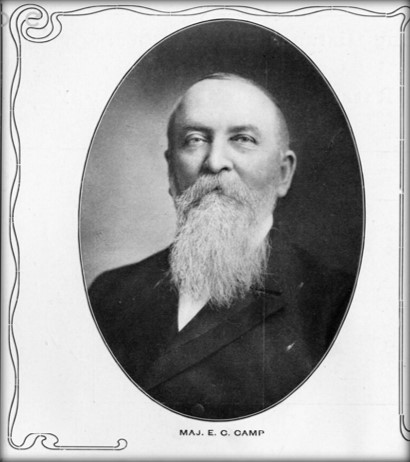

In 1915, major financier Eldad Cicero Camp (the former Union officer noted both for shooting former Confederate Col. Henry Ashby to death in 1868—and for building the 1890 Greystone mansion on Broadway), established the Camp Home for Friendless Women at the northeast corner of East Jackson and Florida Street, for women in peril from the drugs, violence, and abuse inherent in the neighborhood. Camp had previously sponsored the first Florence Crittenton Home, which had temporarily fallen on hard times; the Camp Home, a three-story brick building, was likely earnest in intention, an outgrowth of the idealistic progressive era. It apparently served its original purpose well, for a few years, as an amenity not unlike the YWCA, and was even expanded in 1917.

Camp died in 1920, and after that, it seems to have developed a different and less idealistic purpose. In 1921, after the county workhouse abolished its “female branch,” the second floor of the Camp Home became a “temporary detention home.” It was a sort of holding tank in association with the Knoxville jail, which had inadequate facilities for female prisoners. Some of its inmates were drug addicts, some of them venereal-disease patients, some mentally ill, some merely women who were unable to pay a fine for a drunk and disorderly charge. It originally included a “dungeon” for the unruly. By 1924, it was referred to as “the city detention house for women.” Later it was casually called a “workhouse.” Some inmates escaped; some others committed suicide.

It was home to as many as 32 women at a time, sometimes as young as 13. It lasted there more than half a century, as awkward evidence of the city’s indecision about how to deal with girls and women accused of crimes.

Vice remained an issue in the neighborhood, which during prohibition became central to the bootlegging trade. In April, 1916, two police patrolmen in plain clothes raided a “Negro resort” owned by Green Swinney at 514 Campbell Avenue, where the inhabitants were believed to be storing and selling illegal alcoholic beverages. Patrolmen James M. “Matt” Tillery and Rice Witt entered the house to search it, and Tillery was shot twice in the back, dying within moments but not before firing back at a fleeing assailant. Tillery was the ninth member of the force to be shot to death on the job, and the seventh to be killed in the Bowery / Cripple Creek area.

Wesley Nichols, a white man who said he was on the premises to buy liquor, was charged with murder. He pled self-defense, claiming that he thought Tillery, in plain clothes and his badge obscure, was a robber, and that Tillery fired first. Nichols was convicted of second-degree murder, but got a new trial, and the second verdict was voluntary manslaughter. His request for a third trial made it to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which affirmed his sentence despite Nichols’ plea that he would make a fine soldier in the Great War. Nichols last appears in the papers in February, 1918, when he began serving two to 10 at Brushy Mountain.

This same era was the childhood of James Herman Robinson (1907-1972), perhaps the most famous person to have grown up in Cripple Creek. Later an internationally prominent Presbyterian minister, his organization Crossroads Africa, established in the 1950s, is regarded as a forerunner to the Peace Corps. His autobiography, Road Without Turning, includes harrowing memories of horrific flooding, disease, and gang violence, some of it racially motivated, in the Cripple Creek area. “The feeling between whites and Negroes, which did not escape us as children, was hardly more than an armed and uneasy truce.”

The worst of it, by his account, was the flooding; his childhood memories included watching the rising water, with floating garbage, the contents of outhouses, “drowned dogs and poultry” rising all around them, as he stood on his family’s roof and watched neighbors’ houses destroyed.

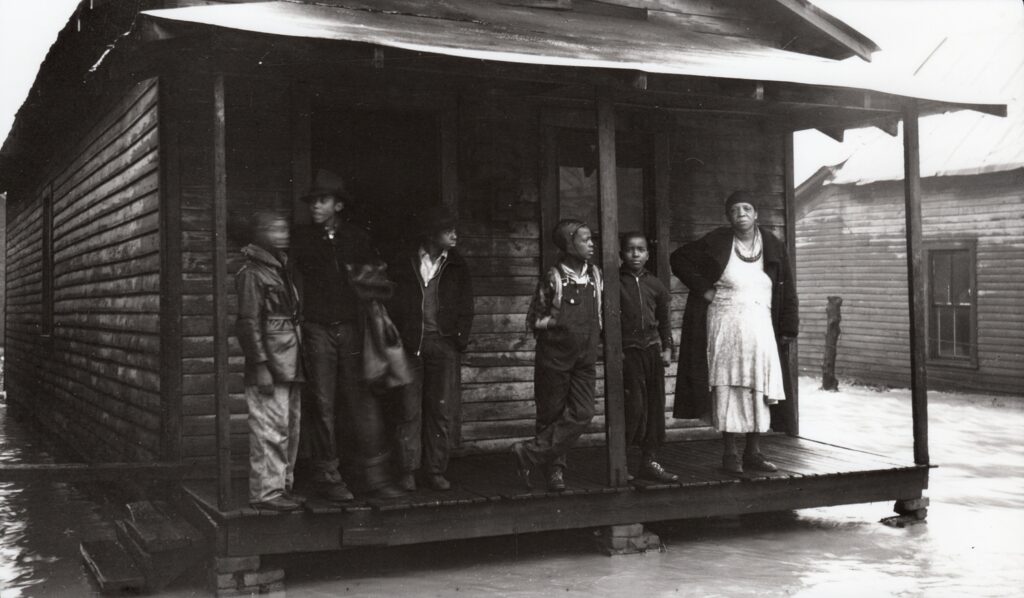

Robinson describes “the Bottoms,” as he called the neighborhood as he knew it, ca. 1912-1917, as “the lowest part of town, geographically, morally, and economically. Our homes in the Bottoms were hardly more than rickety shacks, clustered on stilts like Daddy Long Legs along the slimy bank or putrid and evil-smelling Cripple Creek. Hemmed in by the muddy creek bank on one side, by tobacco warehouses and a foundry on another, and by slaughter pens on a third, it was a world set apart and excluded.” His descriptions make it sound as if he lived right within the project site.

***

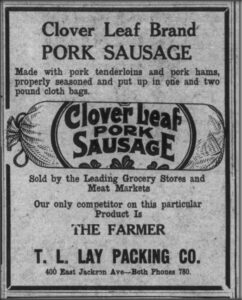

Lay’s Packing Co. had its origins as a meat market along Central around the turn of the century. Tillman L. Lay (1865-1951), who had grown up on a farm in Union County, first worked as a carpenter before he opened his first meat grocery store on Georgia Street in 1890. He was specializing in meats by 1907, when he had a simple butcher shop at 141 S. Central—just as his cousin, Jim Lay, was obliged by law to close his saloon down the sidewalk at 135.

Ambitious to grow his business, T.L. Lay began processing his own meat, beginning with livestock, in the early 1920s. By 1922, he had acquired some land on Jackson just east of Patton Street for a modern packing plant. Lay’s originally sold just to markets in East Tennessee, but with refrigeration and a fleet of trucks, in 1925 earned a USDA license to sell in other states, and Lay’s products became known first in Kentucky and then in the Carolinas.

He had four sons who all worked for the growing company. Even as Lay expanded their operations, the company became overextended, and nearly had to close at least twice between 1925 and 1933, but always recovered.

He had four sons who all worked for the growing company. Even as Lay expanded their operations, the company became overextended, and nearly had to close at least twice between 1925 and 1933, but always recovered.

Lay’s eventually became known for its own brands of retail products, like the Three Little Pigs line of meats, as well as Touchdown Franks, Ole Timer Sausage, and multiple luncheon meats. By then, Lay was employing close to 400, many of them reportedly from the neighborhood.

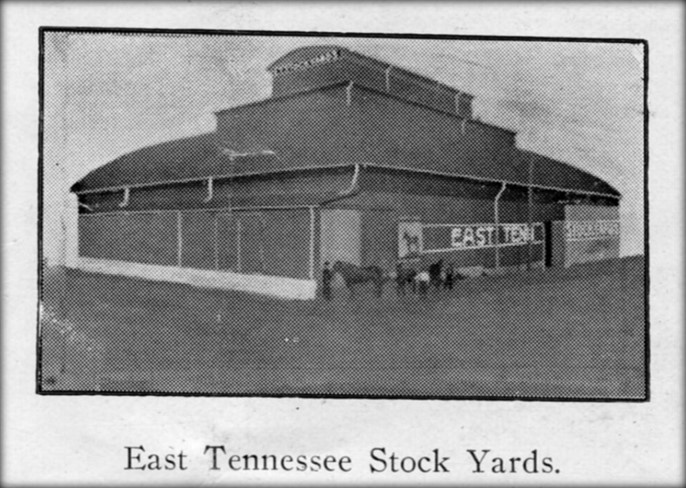

To serve the growing meatpacking industry in the area, there was a stockyard on East Jackson alongside the railroad tracks by 1903, but the larger and more prominent Union Stockyard, serving several meatpacking facilities, including Armour, Swift, and Lay’s. The new stockyard opened along Willow Avenue in 1928, immediately to the west of the project site. As a result, there were periods when large numbers of cattle, pigs, and horses were herded through the streets, especially around Willow, Jackson, and Patton.

Meanwhile, in the late 1920s, a progressive city administration made proposals about rechanneling wildly twisty First Creek to place it all in a line south of Willow Avenue. That plan would be realized about 25 years later.

While most of the residential neighborhood was African American, the westernmost blocks of Willow, East Jackson, and Patton also developed a more rural reputation, with multiple businesses catering to farmers in town to sell stock, buy feed or fertilizer, shop for farming tools or machinery, or attend cattle auctions at the stockyard. By some accounts, a vacant lot off Willow played a role in the history of country music, by hosting “medicine shows” featuring early performers like Roy Acuff.

Another stockyard, the Tennessee Valley Stockyards, was located adjacent to that site on Patton, but closed during World War II. Its land was up for sale, and purchasing it in 1944 was one Cas Walker. Walker, who was then on City Council and known for his country-music shows on the radio, had never been afraid of the Bottom, and had run stores on Florida Street and Willow as early as 1930. In 1944 he chose Patton Street to be both a store and a warehouse/center of operations for his other stores. He seems not to have stayed there long. After he was the victim of a professional safecracker’s visit, he closed that store in 1949, just five years after he bought the property, and no longer did business in the Bottom.

Robert Booker, historian and community leader, grew up in the Bottom in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, and his memories, collected in his autobiographical narrative, From the Bottom Up, are invaluable.

“While most people worked as laborers and housekeepers, some drove trucks and worked as brickmasons and concrete finishers,” he recalls of his neighbors. “A few worked in the city’s meatpacking plants. At least two were teachers in the school system. The area of the Bottom was so large, it was impossible to know everyone and how they made a living.”

Although he knew people who worked at Lay’s, he recalls, “It always bothered me to walk by that plant when they were slaughtering pigs. I refused to eat meat for the next few days until I could get the squeals out of my mind. Then I went back to my hot dogs, ham sandwiches, and pork chops.”

“The Bottom was home, but it was something else! One could see ‘floating’ crap games. Bootleggers were plentiful. Houses of prostitution were available. During the early spring First Creek roared from its banks and forced residents close to it from their homes.”

***

First Creek became much tamer in the early 1940s, with the Tennessee Valley Authority’s completion of Douglas, Cherokee, and Fort Loudoun Dams; some of these projects were hurried up for the war effort, which demanded hydroelectric power. After those dams were completed, First Creek was still subject to flash flooding, but not the more substantial and longer-lasting flooding associated with the Tennessee River rising beyond its banks.

However, First Creek was still seen as a problem, its banks considered unsafe for human habitation, partly because it was associated with untreated sewage, some of it from miles upstream.

Urban Renewal materialized as a series of major changes in the postwar period, enabled by the federal government, but to a large extent interpreted and directed at the local level. Urban Renewal in Knoxville was a comprehensive and complicated 20-year effort—or ordeal—involving hundreds of planners and administrators, and thousands of displaced residents and business owners. Knoxville’s experience with Urban Renewal, by whatever name, deserves a book-length treatment, or more, well beyond the scope of this report.

One arguable precedent was a federally funded effort in 1947 to attempt to re-channel First Creek. It apparently didn’t call for moving many residents. It’s interesting to note that the chief engineer in one of these early projects was former U.S. Navy Admiral Husband Kimmel, criticized by some for lack of readiness for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. He lived in Knoxville for several months in 1947 while working on the project.

More work was done about rechanneling First Creek about five years later, partly under the auspices of the Knoxville Housing Authority, when the creek was successfully channeled to flow entirely to the south of Willow.

The Housing Act of 1949, passed during the Truman administration, was an attempt to encourage cities to clear their worst slums with the help of private developers. The act became stronger during the Eisenhower administration in 1954, as cities began using federal funds and the force of eminent domain to address perceived problems with substandard housing.

Here it was administered by the Knoxville Housing Authority, formed in the 1930s as an outgrowth of the New Deal as a way to build modern housing with electricity and plumbing for those unable to afford it. Supervising and approving the process were the mayor and Knoxville City Council, as well as the Metropolitan Planning Commission, a new and more vigorous form of an earlier organization called the City Planning Commission.

It might be relevant to note that although Urban Renewal arrived at the very end of the era of strict segregation, Knoxville’s city government was still overwhelmingly white; the mayor and City Council were entirely white and entirely male. The relatively new Metropolitan Planning Commission, which reviewed much of the Urban Renewal progress, did have one African American member, Dr. James Colston, the president of Knoxville College, who joined the body in 1956, and remained for eight years. The Knoxville Housing Authority appears to have been all white until 1968, when Lee Williams, M.D., joined it.

In Knoxville the program had multiple administrators through the KHA, the MPC, and through five mayoral administrations and dozens of councilmen, involving scores of consultants from Atlanta, Memphis, Washington, and elsewhere. However, it’s not obvious that many local African American citizens or community leaders were polled about the wisdom of the demolitions that were to come.

Many of Urban Renewal’s administrators, including the mayor whose administration started it and the MPC’s first executive director, died before the project was completed, and probably never heard it criticized.

Perhaps adding some urgency to the issue was that the ’50s were not a good decade for Knoxville, which saw several of its larger employers, like Brookside Mills, close; the city lost 10 percent of its population, marking the most precipitous population decline of any American city that decade. The city was reportedly behind in taking care of its poorest, thousands of members of both races lived with substandard plumbing or electricity, or lacked them altogether.

The city was smarting from a series of criticisms in the national press, some bordering on ridicule, for the shabby appearance of its downtown. (In 1947, travel journalist John Gunther had called it “the ugliest city … in America”; in the early 1950s, Look and Fortune magazines both criticized the city’s appearance and persistent problems with vice.)

At first Knoxville was criticized for being slow to get on board the Urban Renewal train, while other cities like Nashville and Chattanooga jumped at the chance to earn millions in federal funding for major city projects.

The first wave of the Willow Street – Lake Loudon Project called for moving all residents from the lowland area.

Ironically, Urban Renewal’s multi-pronged approach made the bottomland much safer to live in, while also insisting that people stop living there.

***

According to the city directory of 1950, right about 100 African American households were living along the parts of Campbell, Quebec Place (a.k.a. King’s Alley), East Jackson, Willow, Florida, and Patton within the development section (bounded by Patton, East Jackson, Florida, and First Creek, but including both sides of each street). Some of these residences were very modest; most seem not to have been served by telephones at the time. Many were tucked in between businesses.

How many individual residents were displaced, in total, is hard to guess without thorough research into the census records. Some were likely single, but some were also likely family groups. It was not unusual for six, eight, or more people to live in the same small house. Records suggest the possibility that 200 or more people lived within the project site.

There appear to have been a very small number of white people in the same area, a shopkeeper or two who lived above a business. Several retail businesses, owned by both African Americans and whites, were removed by the project.

Among the white-owned were the Hutchens Cafe, at 324 E. Jackson; Margaret’s Cafe, at 320 E. Jackson; Pappas Sales, a used-clothing store, at 322 E. Jackson; Rittenberry’s Place, a beer store, at 326 E. Jackson; Checkerboard Feed Store, at 327 E. Jackson; a warehouse for the R. J. Quigg Chemical Co., at 329 E. Jackson; Ragland Bros. Wholesale groceries, 401 E. Jackson; Justus & Co. Farm Machinery, 500 E. Jackson, as well as Justus Hatchery, at 506; Simmons Co. wholesale bedding, 503 E. Jackson; Knoxville Beverage Co., at 509 E. Jackson; Security Feed Store, at 510 E. Jackson; Specialty Foods, at 521 E. Jackson; KMC Co. wholesale grocery at 601 E. Jackson; Smelcher Furniture Co., at 608 E. Jackson; Beaver Motor Co., at 701 East Jackson; the H.K. Hurst Furniture Auction Co.; the Cas Walker Grocery on Patton; Cureton Cafe; Huffman Refrigeration Jobbers; Brown-Stubbs Coal, at 621 Willow; the Iddins Machinery Co. at 412 Willow; and George P. Shiflett, who was in the early years of a prominent career as a veterinarian (he even attended to UT’s Smoky) had an office at 414 Willow, to appeal to farmers dealing with the stockyards.

Black-owned businesses displaced included the Willow Street Grocery; Bussey’s Beauty Shop, at 713 E. Jackson; Wade’s Beer Parlor at 704 ½ Willow; Harden’s Grocery at 615 Willow; the Florida Lunch, at 129 Florida; the well-known Shady Corner Grocery, at 115 Florida; Green’s Pool Room, at 218 Florida; Harris Beer Store, at 641 Willow; the Union Front (a restaurant) at 404 Willow; the Silver Front, 617 Willow. There was also a Church of God at 608 Willow.

The Shady Corner Grocery, run by Mrs. Julia Hicks, is fondly remembered by Robert Booker, as the place at Florida and East Jackson where he worked in seventh grade, in the late 1940s.

Booker also recalls Pinkston’s Grocery, a white-owned business run by Paul Pinkston, father of the man of the same name who founded South Knoxville’s well-known Pinkston Motors. The elder Pinkston had operated groceries on East Jackson and Florida Street. Pinkston, Booker says, was a good friend to his family.

Also on Campbell, near Willow, was the Tabernacle Baptist Church, which was Booker’s home church. Used for industrial purposes in recent decades, at least part of that building, originally at 600 Campbell Ave., remained until the recent Lay’s site demolition.

Of special note is Andrew’s Weiner Stand at 618 Willow; its proprietor was Andrew Taylor, who was famous within both the African American and white community not mainly for his hot dogs, but for his unusual homemade tamales. He may have been the last legacy of Harry Royston’s innovation, though some memories suggest his recipe was significantly different. Booker recalls it: “Just back of the Lay Company was Andrew’s Hot Tamale Stand on Patton Street between Jackson Avenue and Campbell Avenue. His five-cent hot dogs were a real treat and the ten-cent tamales were even better. We did not eat them too often because those nickels and dimes were not easily had. I remember when he moved from the Patton Street site, as Lay’s was making plans to expand its facility, to a new building he erected on Willow Avenue. Urban Renewal later took it and he moved to Linden Avenue in the late 1950s. He finally gave up his business when the Morningside housing development took his property.”

The Camp Home, now for Delinquent Women, remained through most of the Urban Renewal era at 702 East Jackson, at the northeast corner of the project site. It was segregated, and housed both Black and white women on different floors. An awkward combination of public and private service at best, it devolved from its original stated intent, as a refuge for distressed women who might be tempted by drugs or crime, to a sort of privately owned prison.

Robert Booker remembers it vividly, in all its contradictions. “The most beautiful lawn in the Bottom was at the corner of Jackson Avenue and Florida Street. It was the front yard of the Camp Home and just too tempting to resist. We just had to wrestle on it or roll on it just for fun. Very few children had grass in their front yards because it had all been worn away from playing on it…. The Camp Home was a facility for wayward women…a place of incarceration for women convicted of prostitution, shoplifting, and other low-level crimes. It was nearly a block long and had three floors. The first floor was for offices, the kitchen, etc. One floor was for white women and the other for black women. Two older white women were in charge of it, and Miss Dolly, a Black woman, was the cook and laundress in the 1940s and early 1950s.”

It remained intact after the first wave of demolitions, but was subject to serious allegations, made by inmates in the late 1960s, that the supervisors knowingly cooperated with a Newport-based scheme to pay the fines of the incarcerated women in exchange for their employment as prostitutes. On the motion of Councilman Cas Walker—who nonetheless defended its final administrator–it was closed in 1969, when the Safety Building opened. It’s unclear whether its “matron,” Edna Crane, appointed years earlier by Mayor John Duncan, and a major subject of the allegations, ever faced charges. When last mentioned in the News-Sentinel in the summer of 1969, she’s officially “on vacation.”

Its building was still standing in 1971, when it became a training center for the blind, a purpose it served for about a decade. It was torn down in 1987 for a new warehouse.

***

The approximately 100 African American households in the project site were probably among the first people moved by urban renewal. The Knoxville Housing Authority (KHA) purchased the land at market value. However, it was very cheap land, and those who did own their own homes probably had difficulty finding any lots of comparable cost.

While calling the Willow Street area unfit for residential occupation, Urban Renewal’s plan favored industrial use, like T.L. Lay, which was becoming one of downtown’s biggest employers, with a biracial workforce.

T.L. Lay purchased the land from KHA, much of it for as little as one dollar per square foot. The company announced a series of expansions between 1958 and 1963, stretching their plant across the block to Willow and apparently resulting in the familiar Lay’s factory visible there in recent years.

However, the Union Stockyard did have to move. Moving it away from downtown had been on the agenda of City Council for years, delayed mainly by the inability to find a city community that would tolerate it. In 1958, using Urban Renewal resources, they finally made a deal to move it to the closed Broadway Speedway, a former stock-car racing track in Halls.

In spite of the loss of the stockyard that started it, Willow retained some of its rural/agricultural character for decades to come, as an address for businesses aimed at farmers.

The two corporate meatpackers closed their East Jackson facilities, leaving only Lay’s, the home team in the Bottom.

By 1985, Lay’s employed 350 in its complex operations, which included a computerized laboratory for testing meats.

Corporate competition was hard on Lay’s. In 1990, the company laid off one third of its workforce. A decade later, Lay’s, a family-owned business since its founding, sold to a group of investors in Maine. A year later, they declared bankruptcy, and in 2002, closed the business for good. Lay’s little market to the east held on for a few more years before closing.

The big plant became an unusual warehouse for Knox Rail Salvage.

Although some companies did business down there, the area saw little development in the late 20th and early 21st century. Most of the site of the old stockyard became a parking lot. Some new residences went in east of the development area, and a few new businesses on East Depot seemed to suggest promise for a revival of the area, but dreams of redeveloping some sites, like the ca. 1920 Keller Foundry alongside First Creek at 1010 East Jackson, ended when it was torn down around 2015 by a new owner with other plans for the property.

In Spring, 2015, the Dogwood Arts Festival’s very popular Rhythm n’ Blooms music festival moved to a seemingly unlikely location, the large parking lots just west of Patton, underneath the highway. In doing so, it revived an old name for the area: The festival’s main stage, for the most popular headliners, was dubbed the Cripple Creek Stage. It hosted a wide variety of performers in its first five years there, including the Decembrists, Drive By Truckers, Tank and the Bangas, Dawes, Gogol Bordello, Young the Giant, and Tyler Childers, each one drawing thousands of attendees.

It was an interesting homage to the music that was once a part of the place.

In 2017, developers owning a piece of property on Willow Street paid homage to an institution that had left the area almost 60 years earlier, with the announcement of an apartment complex called Stockyard Lofts.

***

Note: This is a narrative history from the best available sources, put together in a period of less than two weeks. Although we believe it’s a good outline of the history of this interesting and complex place, it should be considered only a starting point for further research.

Demolition of Lay’s Meat Packing Plant, Between Willow and Jackson, Knoxville, March 5, 2021 (insideofknoxville.com)

Sources:

Personal interview with Robert Booker, historian and former resident, May 11, 2021.

Knoxville City Directories, on the shelves at the Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection.

Business files at the McClung Collection, especially concerning Lay’s.

Multiple maps, most of them available at the McClung Collection.

Staffers at Beck Cultural Exchange Center and meetings with Beck’s Cultural Corridor committee.

Knoxville Sentinel, Knoxville News-Sentinel, Knoxville Journal & Tribune, and Knoxville Journal articles retrieved from the Knoxville Public Library and newspapers.com.

Research gleaned from Jack Neely’s Knoxville’s Old City: A Short History.

Recommended Reading:

James Herman Robinson, Road Without Turning (1950)

Henry Spencer Booth’s “A Trip through Knoxville’s Foreign Mission Quarters” (1912) at the McClung Collection.

“A Night on the Bowery,” unsigned feature story, Knoxville Journal, July, 1900.

Robert Booker, From the Bottom Up (undated)