The Big 1-8-0

After more than half a century of claiming it, are we finally there?

by Jack Neely

Surely you’ve heard there’s a lot of anxiety about the census, about Congressional redistricting, whether undocumented immigrants are likely to be counted, whether the coronavirus curtailed it in general. Usually the census is like the Coast Guard, not famous or exciting but dependable, and there when you need it. But the 2020 census is different, the most controversial census I recall.

Knoxville has a different anxiety about the same census. It’s in the deep recesses of Knoxville’s mind, a nagging question we rarely dare to ask. It’s this:

After all these years, are we finally as big as we said we were in 1962?

That was the year of the big Annexation—when, for the first time, Bearden, Fountain City, and several other large unincorporated tracts that had previously been considered rural or suburban were finally brought into the fold, and considered part of Knoxville. In these places was both rejoicing and mourning: Property taxes would be higher, but most services were much better. City school schools were better funded, and public libraries were nonexistent outside of city limits. Trash and brush pickup was free. And there would even be sewers; before annexation, even Bearden residents were obliged to install septic tanks, and get them pumped out regularly.

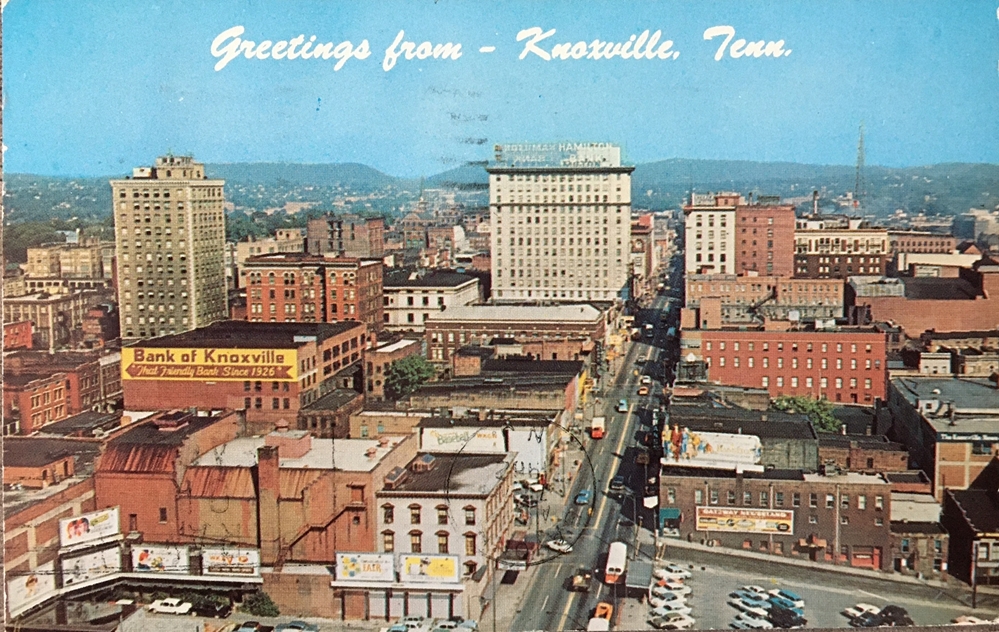

In 1962, using real numbers extrapolated from the 1960 census—when pre-annexation Knoxville still had a trolley-era footprint, and city’s population was just under 112,000, and some ball-park estimates of the major populated areas that had been added to the city, plus some conservative optimism about growth, Knoxville became—according to the Chamber of Commerce—a city of “about 180,000.”

“This is Knoxville, Tennessee,” said Mayor John Duncan, in a March, 1963 speech, “population 180,000….” Through the 1960s, several other writers and civic leaders used that estimate, having no reason to question it.

Mayor Duncan didn’t live to see his hometown prove it was that big.

It wasn’t the most extravagant estimate of Knoxville’s size in the 1960s. Using its own data, based on their list of Knoxvillians age 16 and over, and a “multiplier” to indicate those they didn’t catch and everyone’s children, the City Directory was estimating in 1964 that the city had a population of over 300,000.

That more-conservative estimate of 180,000 seemed perfectly realistic until the real Census of 1970. During the Nixon administration, Knoxville proved to have not 180,000, not even 175,000, but only 174,587.

Surely it was a mistake, due to hippies hiding from the federal authorities, astrally projecting themselves elsewhere when the knock came at the door.

Did the city have grounds to complain? I don’t know, but perhaps in response to the presumption of an undercount, in 1975, the census offered a new estimate for the presumably growing city at 180,447.

It was the Jimmy Carter administration when we had another census. And it proved we were bigger than we had been in 1970—just about 460 people bigger. You could seat all the additional population of a decade in the recently refurbished Bijou Theatre. The city already planning a world’s fair was just 175, 045.

Well. That was closer to 180,000 than 170,000, giving us a better mathematical claim to our favorite estimate than we’d had in 1970. Rounded to the nearest 10,000, Knoxville was indeed a city of 180,000.

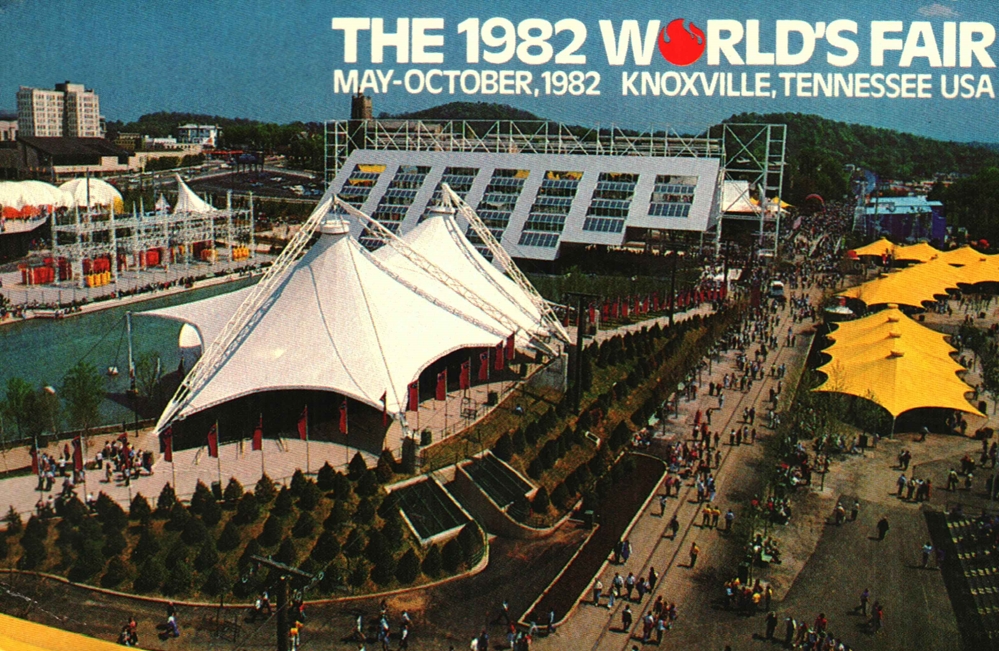

But in real numbers, there was still a big gap. Surely we’d get there for real in the 1980s. After all, Knoxville welcomed 11 million people to the World’s Fair. The city had more nightclub shows, a regular diet of traveling bands, some of them famous or soon to be. Our favorite actor, David Keith, was suddenly in several big movies. Johnny Majors’ Tennessee Vols won two SEC championships—and Pat Summitt’s Lady Vols were winning their first national championships. Some Knoxvillians had bought Esquire Magazine, and didn’t move to New York, as all publishers were supposed to.

Knoxville itself was the subject of dozens of magazine articles. As one municipal leader noted, for the first time in his memory, in the national media Knoxville wasn’t “Knoxville, Tennessee.” It was just “Knoxville.” Americans had heard of the place, and didn’t have to be told where it was.

But what happened in the 1980s, when “the scruffy little city” got more national press than Knoxville had gotten since the Civil War? By 1990, surely, the modest estimate of “180,000” would be a distant memory. It was just a matter of waiting until 1990 to prove how big we really were.

But that year brought a shock. The city’s population didn’t grow in its World’s Fair decade. It declined. It fell more than 5 percent. It was, in fact, the second most precipitous decline in history. According to the George H.W. Bush census, Knoxville was officially a city, if you can call it that, of only 165,121.

What happened? While we weren’t looking, maybe several things. The Reagan years had been hard on the Tennessee Valley Authority, which had once been Knoxville’s biggest employer. TVA lost more than half of its staff during that decade, and many of its erstwhile staffers perhaps found work elsewhere in the country. A couple of our biggest banks collapsed. Some old-line industries got bought out, cut back, or closed forever, like Dempster Brothers, creators of the famous Dumpster and for half a century, a major employer. Also, the University of Tennessee’s original campus, which was roaring in the 1970s, shriveled a little in the ’80s, partly due to tougher qualifications for student loans, partly due to the expansion of other public-college campuses across the state, both community colleges and enhanced campuses of UT’s own system.

But the fact that the county population did not decline during that decade that Knoxville declined–in fact it grew by 17,000–suggests there may be something else at work. A new style of housing, not yet branded as the “McMansion,” was sprouting beyond city limits in all directions, prompting the stylish to build large houses on inexpensive rural land in new subdivisions, from Lyons Bend to Hardin Valley to Halls. Modestly affluent homeowners could take their tax savings and reserve it for payments on a swimming pool, a luxury master bath, and a few extra gables.

These folks hadn’t died or moved away. They were still here, showing up at football games, still shopping at the malls. They just weren’t paying city taxes anymore, or voting for City Council—or being counted by the U.S. Census as “Knoxvillians.”

Whatever the chief culprit, there were about 10,000 fewer Knoxvillians in 1990 than there had been a decade before.

By 2000, as we heralded the reviving downtown, with hundreds of new apartment residents and street cafes and brewpubs, and concerts on Market Square attended by thousands, the city was seeming more “urban” than ever. That was the word we were getting used to hearing in a positive way. There was anecdotal evidence of people leaving their suburban homes to live in downtown condos. We looked to the census with expectations of mathematical proof that something impressive was happening here.

And at the beginning of a new millennium, Knoxville showed a population of 173,890.

Well. Bigger than it had been in 1990. Not quite as big as we were in 1970. Not nearly as big as we said we already were in 1963.

And downtown’s district didn’t show the dramatic increase that some of us hoped to see.

To be fair, that year some downtowners actually complained that they weren’t counted. The census takers apparently didn’t guess that people were actually living in old produce warehouses. It was the first time I was ever aware the Census sometimes made mistakes. But once they publish the numbers, they don’t go back and correct them.

After that, the first decade of a bold new century, brought more dramatic proof of a demographic sea change.

We were soon welcoming new and bigger festivals than ever before, Rossini, Hola, Big Ears, First Fridays, with crowds estimated by the police at 10,000, 20,000, even 40,000. Greenways were growing, and being used more than ever before. Adults were riding bicycles, even though they were in Knoxville. Market Square and the Tennessee Theatre had major makeovers. Downtown there were big-ticket performances more nights than not, and people were packing the historic theaters to see them. The new multi-screen Regal Riviera was a hit. Restaurants, each one different from all the others, and specialty bars and brewpubs multiplied. Hang around downtown after dark, and Market Square or the 400 block of Gay could seem just like a big city, livelier at 10 p.m. than most blocks of Manhattan.

By then, it was a common assumption. “Knoxville’s so much bigger than it used to be!” Stand on Gay Street in 2010, and you wouldn’t have to wait long before you heard a friend or stranger say that.

And maybe it was. But not by much.

The Obama census registered 178,874.

Not quite as many as Mayor Duncan said lived here back in 1963. We were still just 1,126 short of 180,000. One full house of newcomers at the Tennessee Theatre would have put us over. But it didn’t.

Mayor Duncan died 32 years ago, and didn’t live to see his city become, officially, as big as he said it was back during the Kennedy administration.

I think we’ve proved that size alone doesn’t necessarily count for much. The city that was still mostly segregated, and forbade liquor and wine by the drink, changed radically, hosted a world’s fair, created 100 miles of greenways and a couple of extraordinary parks, opened a new art museum, then a history museum, grew its Zoo to something nationally notable, witnessed its favorite football team win a national championship, later hosted a significant international annual music festival, all without changing its municipal size much. Not more people, just different ones.

The official census estimates say we got there a few years ago. On the real census, will we live to see Knoxville hit the big 1-8-0? It might be nice to see. But have we proven that it doesn’t matter?

###