Mead’s and Ross Marble Quarries

Mystery and Magic at Mead’s and Ross Marble Quarries

Just a five-minute drive from downtown Knoxville you can find a mysterious and magical natural place to explore like none other in Tennessee. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, both Mead’s and Ross Marble Quarries within Ijams Nature Center transport visitors to a different world – a world of never-ending surprises.

Nature is tenacious. Given enough time, it can seemingly reclaim any landscape. Where life exists, grows, and thrives, nature always finds a way. Where once scarred land was littered with the empty shells of derelict buildings, industrial overburden and scattered blocks of Tennessee Marble, now sits a beautiful and expansive greenspace enjoyed by hordes of people. Where once there were thousands of piles of industrial and domestic junk there are now nature trails, gorgeous overlooks and historic and natural interpretation allowing visitors to understand the potency of this special place.

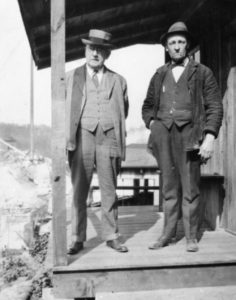

Frank Mead, on the left, who Mead’s Quarry is named. The man on the right is a Mr. Harmon, title unknown. McClung Historical Collection.

Known as the “Marble City” in the 19th century, Knoxville has a long history of marble quarrying. Back then the Ross Marble Company paid a small fee for land adjacent to what would soon become the Ijams Bird Sanctuary and opened up a quarry to extract Tennessee Marble, a highly polishable stone that was in great demand for grand buildings as well as national monuments. The site later became locally known as Mead’s Quarry in honor of Frank S. Mead, the company’s first president.

The quarry sites employed hundreds of workers to handle steam- channeling machines that pried huge blocks of stone from the rock face. It was a dangerous and often fearsome place that operated 24 hours a day and a few senior Ijams neighbors still recall the piercing sound of the daily blasting siren.

All told, East Tennessee quarries supplied Tennessee Marble for numerous Knoxville structures and also iconic buildings such as the J.P. Morgan Library in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. By the Great Depression, however, demand for the marble had drastically declined and quarrying operations everywhere hit hard times. Switching to gravel and limestone production, both quarries here limped along for several decades but in 1978 both were defunct and, particularly Mead’s Quarry, became illegal dump sites and local eyesores.

Today, following thousands of volunteer cleanup hours and the dedication of Ijams park staff, the quarries have expanded Ijams to a new level and acted as the catalyst to the emerging and nationally-lauded Knoxville’s Urban Wilderness, created and championed by Legacy Parks Foundation, which offers over 40 miles of trails within South Knoxville alone.

Mead’s and Ross Marble Quarries are unique places along the Urban Wilderness. The quarries, acquired during the past decade, now encompass almost two-thirds of Ijams’ acreage. The former home site of the Ijams family still sits on the bank of the Tennessee River less than a mile away yet the quarries both compliment and challenge one’s view of a traditional nature center experience.

Starting at the parking to Mead’s Quarry, just down the road from the main Ijams entrance the visitor can spend all day exploring history, natural and man-made landmarks, as well as enjoy the sights and sounds of local fauna. Immediately, a 25-acre lake pops into view, created toward the end of mining operations, which is now home to native aquatic species and, curiously, fresh water jellyfish that rise to the surface in the hot summer months during their reproductive cycle. Despite being just the size of a “quarter”, the notion of a jellyfish alive in East Tennessee is remarkable to most people yet it’s a species that enjoys fresh water. This is quite a discovery for a location with such a murky history as Mead’s Quarry where dumping and crime prevailed unchecked for a long time.

A good way to first explore Mead’s Quarry is to take Tharp Trace Trail that circles the lake on the upper bluff. Quite steep in places, the trail offers a fine view looking down at the site and another of the Great Smoky Mountains from one of two overlooks near Stanton Cemetery. Formerly known as the Dempsey Johnson Cemetery, the name changed when the site evolved into a community cemetery during the 20th century.

Johnson family reunion, 1880. Courtesy of Mary Farmer.

Interpretation shows a photograph of the Johnson family reunion in 1880 conveying the story of Mr. and Mrs. Dempsey Johnson whose graves still face east-west; they were laid to rest head-to-head because they were divorced in life.

Back down on the plaza where the lime kilns once stood, another sign depicts a panoramic view of the quarry facility during the 1920s, and gives an indication of how the features of the land today are informed by the past. You can see clearly the extent of how the hillside was turned into a bluff by persistent mining. The past echoes of industrial mania are now eclipsed by the calm buzzing of dragonflies, songbirds, and occasional visits by interesting migratory birds like a pair of red-headed ducks that paused during their migration to rest on the lake one season.

Ross Marble Quarry is situated to the south of Mead’s Quarry and offers quite a different experience. There is no lake here but a dry ravine extending along the quarry vein lined with imposing cliffs. The most memorable feature is not natural at all but a man-made rock bridge that was built by quarry workers, likely during the 1950s, to save time moving men and machinery from one side of the pit to the other. Huge blocks (unsuitable for polishing) were piled up jigsaw-fashion to form a wall with an entrance, eight-feet tall, to pass through. This is now known as the “Keyhole.”

Stepping through the entrance, stone steps lead down into the former pit where visitors can look up and see “God’s Chair” – a name coined by locals to describe the giant “shelves” of limestone akin to Mayan ruins. Such views cement themselves in the mind, creating a compelling sense of place. Long gone may be the former dwellings and offices, as well as the wooden ladders that workers used to climb up and down out of the quarry pit. The derrick foundations are still there where one can imagine the crane booms extending from one side to the other to lift the stone blocks out from the quarry to nearby railroad spurs. Since those days, nature has seriously reclaimed itself here with all its randomness of native and exotic species.

Hayworth Hollow maybe a short 0.2 mile trail further down from the “Keyhole” but it’s also a captivating place. The trail winds downward along the quarry gorge lined with a boulder field covered in moss and lichen. It looks as if time has stood still, largely undisturbed for decades. It feels like a portal to another world, evoking the spirit of Skull Island; for at the bottom it’s hard not to imagine a gigantic wooden doorway, a gateway for King Kong himself. It’s that kind of a place; not brooding exactly but hinting of a Land that Time Forgot, a place that truly belies its proximity to the hustle and bustle of downtown market Square just two miles away.

The atmosphere is heightened by the sheer rock walls that tower above Hayworth Hollow where it is strongly believed that the former Ross Marble Quarry workers extracted the huge blocks of marble destined for the National Gallery of Art in the nation’s capital. This fact alone was one of the key reasons why Dr. Susan Knowles with the Center for Historic Preservation wrote a nomination for these sites’ consideration for the National Register of Historic Places. That nomination was successfully approved on the state and national levels.

Berry Cave Salamander. Courtesy Matthew Neimiller, University of Tennessee.

Although hardly discernible, there are actually several cave gates along Hayworth Hollow. Ijams worked with the Tennessee Chapter of the Nature Conservancy to protect the subterranean wildlife habitat through a state Tennessee Landowners Incentive Program grant. Gating the caves proved critical for a number of reasons; visitor safety and the protection of the delicate wildlife populations inhabiting the caves, especially the rare and threatened Berry Cave Salamander, a species that exists in only a handful of caves throughout East Tennessee.

The change in landscape at Ross Marble is also staggering; within a quarter mile of Hayworth Hollow the terrain transitions rapidly from dense, almost tropical forest, to the barren wasteland of the former lime pit, now teeming with spruce trees thriving in the alkaline soil. Over on the Hickory Trail, an area that witnessed low density industry contains a proliferation of old-growth trees that may have escaped logging. During the springtime, wildflowers lining the trail enhance a walk in the woods or an enjoyable ride for mountain bikers.

Whether on foot or bike, there are approximately 12 miles of trails to explore at Ijams, seven of which encompass the quarries. The latest addition, Ross Marble Trail, connects the “Keyhole” to Burnett Ridge Trail and Turnbuckle Trail where visitors can also connect to other trails along Knoxville’s Urban Wilderness, particularly the nearby William Hastie Natural Area. All of the quarry trails (excluding Tharp Trace due to its steepness) are multi-use trails for hikers and mountain bikers. Indeed, many of the trails were designed and built by the Appalachian Mountain Bike Club, a club dedicated to delivering memorable trail experiences for beginners and advanced riders alike.

If you don’t own a mountain bike, you should be able to rent one from the concessionaire at Mead’s Quarry. Canoes and stand-up-paddle-boards are available to rent too. A beer market offers local microbrews as well as drinks and snacks for families and is a fitting place to relax and cool off after spending an afternoon or a full day exploring the Ijams quarries.

These post-industrial sites, overlooked for so long, are now gaining a growing following and reputation for locals as well as tourists. The site’s combined trails, undisturbed woodlands, rocky outcrops, and stunning gorges offer truly unforgettable experiences. Their historical significance is assured. Head on over to Ijams and see for yourself what the buzz is all about.

This article by Paul James originally appeared in the Tennessee Conservation Magazine.

Link to Knoxville-Marble City page