Seeing Our Shadow

The Evolution of our oddest holiday

I had a much more serious subject in mind for this month’s column, but couldn’t find the data I needed in time to complete it. To make a serious point, you need to be convincing, and have all your facts straight. I will return to it. This particular column isn’t very serious. It’s about our oddest holiday.

The origin of holidays is a subject of fascination. As they appear, and inevitably evolve, each turn in the career of a holiday seems to say something about our culture. I’ve looked up most of them, and found lots of surprises. Until this week, I had never looked into Groundhog Day.

Everything about it is odd. From its basic premise, about a rodent’s perception of its shadow, to the fact that it’s about the only holiday on the calendar that’s not celebrated in our homes or places of worship or city streets. We don’t expect Groundhog Day dinners, Groundhog Day gifts, Groundhog Day songs. Still, there it is, every Feb. 2. Groundhog Day is only on the news, briefly and dutifully, usually from an embarrassed-looking meteorologist, and it reminds you of every other time it’s ever been on the news. Punxsatawney Phil usually sees his shadow, and we always have six more weeks of winter. As we already know from those same calendars.

It’s not surprising that it became the premise for an offbeat science-fiction movie about the same day repeating itself forever.

It might seem peculiar that we have a national recognition of the groundhog, especially considering that they’re strangers in most parts of the nation. They’re scarce west of the Mississippi, and in the Deepest South. They don’t get very far south of Chattanooga. Of course they don’t. They’re obviously dressed for winter.

But as you know if you’ve lived here more than a couple of months, Knoxville is well within Groundhog Country.

I’ve seen groundhogs in abundance—the south bank of the river, near the Gay Street Bridge, once contained whole groundhog villages, with trails through the kudzu that seemed to connect multiple holes, like Hobbits. On a long walk from the office, I often looked down at them from the railing of the Gay Street Bridge, envying the apparent simplicity of their lives, but also wondering if they had their own dramas down there, their own Lord of the Rings trilogy that we don’t even know about.

A census would be challenging, but it’s safe to say that within city limits, we have thousands of groundhogs. Many homeowners get annoyed when groundhogs relandscape their manicured lawns. But it’s hard to get angry at them. They seem friendly, affable sorts, and lead an enviable life of society in cozy homes, and often come out to enjoy nice weather, just like we do.

But we rarely keep them as pets. I have never touched one. Have you? Why is the groundhog the only animal that has an annual holiday? I can’t answer that question, and won’t try. But I thought our observance of the oddest of holidays was worth looking into.

A lot of holidays seemed to pop up in the years just after the Civil War, especially between 1865 and 1880. In Knoxville, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, Memorial Day, and Halloween first emerged as public holidays during that festive generation. During the same time, previously observed holidays–Independence Da, Thanksgiving, and especially Christmas–became more popular and more extravagantly celebrated that they ever had been before. Observing holidays seems to be one of the hallmarks of a confident civilization. Groundhog Day is right in there.

That era was also a time when Knoxville was welcoming enough Catholics that even protestants and others were becoming acquainted with Catholic holidays. That may have had something to do with it. The second day of February was Candlemas, an ancient Catholic holiday, commemorating either the purification of Mary or the presentation of Jesus at the Temple, or both. Falling on the 40th day after December 25, it was often observed as the end of the Christmas season, when you could finally undeck your halls.

In Knoxville, as far as I can tell, Groundhog Day is first mentioned in 1869. The Knoxville Daily Press & Herald noted it in a brief item that winter, a bit of unsigned historical drollery that may include an arch disdain for the superstitions of the country people of East Tennessee.

“The country papers, with the usual enterprise for which they are so justly distinguished, have, with scarcely an exception, prophetically considered the weather in their local columns. As judged by the storms of the present week, beginning on Tuesday last, which, we are delighted to learn, was Candlemas Day, or Ground Hog Day, as it is familiarly known among the rural brethren of the editorial profession.”

The writer was probably John Fleming, an Emory & Henry graduate, the editor of the newspaper, as well as a U.S. District Attorney, originally appointed by Lincoln. He considered Groundhog Day a country sort of thing.

“The Ground Hog,” he continued, “in accordance with the traditionary records, came out of his hole on Tuesday, and because of the heavy storm of rain and sleet which prevailed, failed to see his shadow in the sun. Now this little animal is as wise as Jayne’s Almanac, or any of the other annual calendars which all good housekeepers keep hanging on a nail by the fireplace.”

Dr. D. Jayne was a patent-medicine huckster who published a self-promotional almanac, one of several of the Farmer’s Almanac genre. Concerning the groundhog, Fleming continues: “He can see further into futurity than a wise man can see into a grindstone, and he thus became aware that the weather on that day indicated the temperature of the weather for the next six weeks, and as the day was without doubt a stormy one, it naturally followed that the next month and a half will be constituted of mild, balmy days, closing up the winter, and introducing an early spring. The hog, delighted with the pleasant prospect before him, capered about in the mud and rain all day, reluctantly returning to his quarters as twilight drew her dark curtain over the world.

“We therefore advise all good people who believe in the ground hog to look forward to the early entrance of Spring, and in the meantime to go on planting their garden seeds, with an absolute faith in the nurturing tendencies of the coming six weeks of sunny, balmy weather.”

Even as it exhibits some tongue-in-cheek condescension toward country folk, it’s a pretty funny piece. Writing may have run in the family. Fleming was the father of Mary Fleming Meek, who was much later the author of a song you’ve heard before. It begins, “On a hallowed hill in Tennessee, like a beacon shining bright….”

A few more mentions of the new but not new holiday follow in years to come, especially in the Press & Herald.

That’s it. Nothing about Punxsutawney, or a rodent’s perception of his shadow.

In 1879, the Knoxville Daily Tribune offered a brief observance. “This is ‘ground-hog’ day.” Just that. Lower-case, and with quotations that provide some deniability.

In 1883, in a column about a variety of subjects, the Daily Chronicle offered a full paragraph, albeit a vague one concerning the circumstances of how the subject was observed. “Yesterday was ground-hog day. He crept from his hole, and as the sun shone brightly, doubtless saw his shadow. He will not appear again for six weeks, during which time winter will hold its sway.”

In 1887, the Knoxville Sentinel ran the first headline about Groundhog Day: “GROUND-HOG DAY: A Weather Superstition Which Prevails Among Many Nations.” This one’s actually a borrowed story from the Detroit Tribune. It also refers to Candlemas, and “the feast of the Purification of the Virgin.” The article of several paragraphs goes into some fairly complex history of the holiday as it’s observed in multiple European nations, involving the behavior of multiple animals, from hedgehogs to hibernating bears, and assesses it as “one of the days which were taken by the Christian Church directly from the heathen Romans.”

It doesn’t explain everything, but the idea was that the European tradition was translated into the personage of an American rodent. Of course, Knoxvillians always had plenty of groundhogs to observe without anointing one 600 miles away as a national arbiter.

I can’t tell that Knoxvillians were aware that Punxsutawney, Penn., had any particular association with Groundhog Day until 1930, after which the odd name of that small town northeast of Pittsburgh began a semi-regular appearance in Knoxville newspapers.

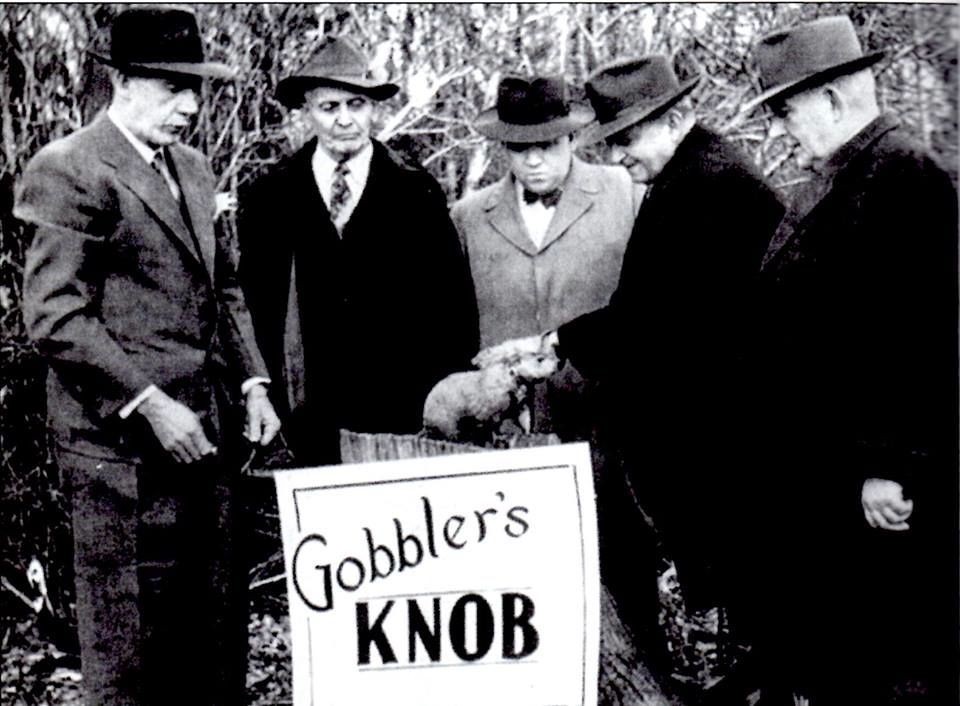

Punxsutawney Phil, who succeeded the deceased and now forgotten Punxsutawney Pete—which, between you and me, sounds like a much better name for a groundhog–has proven to be remarkably long-lived. He was first referenced in the Knoxville press in 1961. His longevity is astonishing, considering the average lifespan of a groundhog in the wild is three to six years.

So why this bizarre custom? Mr. Fleming, back in 1869, offered some clue. It began with one of those weather prognostications of the “red sky at night” and “in like a lion” variety. That if the weather’s like this now, it’ll be like that later. Perhaps it happened that way once, and seemed such a memorable irony that people began expecting it would happen again.

In that first known mention of Groundhog Day in Knoxville, Fleming wrote, “In addition to the prophesies of the ground hog, we also, in order to fortify the timid gardeners, ask our readers to examine the following old Scotch proverb, and say then, if they dare, that the little hedgehog is unworthy of belief:

If Candlemas Day be clear and fair,

Half the winter’s to come or mair [more],

If Candlemas Day be dark and cloudy,

The winter is over and gone alraudy.”

So the groundhog’s not mentioned, and he’s a little beside the point. A sunny Candlemas meant winter wasn’t letting up any time soon. If it’s sunny enough for him to see his shadow, the weather’s nice, but by the contrary reasoning of much folklore, we may get the opposite of that in the weeks to come. When it does indeed happen that way, you tend to remember it.

Jack Neely, January 2022