Of Christmases Long, Long Ago: Knoxville in 1919

Knoxville looked to Christmas as a last desperate opportunity to find something normal about 1919. It had been a strange and unsettling year. Once, years before, the Christmas season had been a wild time, perhaps unknowingly reviving the medieval tradition of Misrule. For people who worked long hours in factories or offices, it was a time for everything to be chaotic, for fireworks and pranks and drunken riots in the streets. Christmas was something to remember. Nobody needed that in 1919.

The year 1919 had started with tardy word of still more deaths from the World War, more than 100 of them young Knoxvillians who had marched down Gay Street two years before, in fresh new uniforms, confident that we Americans were going to polish this European fracas off in no time. And almost as if it was a weird echo of the war, news of the Victory was followed by death and casualty lists, mixed with news of civilians of all races and ages dying here at home, of something called the Spanish flu.

Today we remember 1919 for a bizarre riot involving a frustrated lynch mob, and a confused division of machine-gun wielding soldiers, all firing at barricaded black men on Central. In retrospect, historians have seen the Red Summer riot as the end of a golden era for the city of Knoxville.

By Christmas, 1919, people weren’t even talking about it much anymore; there’d been another deadly riot since then, just a few weeks before Christmas, involving the streetcar strike. For the second time in the year, parts of Knoxville were subject to martial law.

Everything was upside-down in 1919. Automobiles, a novelty a decade before, were suddenly all over the place, making themselves known mainly by causing accidents, running into streetcars, knocking people down as they got off streetcars, often killing people. Something would have to be done.

Things were so crazy that in Knoxville that women had even started voting, several months ahead of ratification of the 19th amendment.

Underlying it all was anxiety about foreign influences, anarchism and communism–or Bolshevism–with its new associations with the violent overthrow of the world as America knew it. Knoxville’s own congressman, J. Will Taylor, was denouncing Emma Goldman, the anarchist, and, perhaps even more unsettling, the advocate of free love. At the same time, Taylor was predicting that Warren G. Harding, the Republican junior senator from Ohio, was one of three candidates most likely to win the presidency in 1920, with Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge another possibility. Taylor’s Christmastime guess seems prescient in retrospect. Harding quietly announced his willingness to run on Dec. 17, but fared poorly in the primaries and didn’t emerge as a major contender until the Republican convention the following June.

Knoxville, like America as a whole, was desperately seeking Normalcy, a new English word first popularized by the Harding campaign.

Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, a former Knoxvillian was showing up on short lists. At UT, the Kappa Sigma fraternity started a “McAdoo Club” to push their old frat brother, former treasury secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, for the presidency. McAdoo, who in Hollywood had just formed, with partners named Chaplin, Pickford, and Fairbanks, an innovative new movie studio called United Artists, never earned the nomination–but he became a key figure in national Democratic politics in the 1920s and early ’30s.

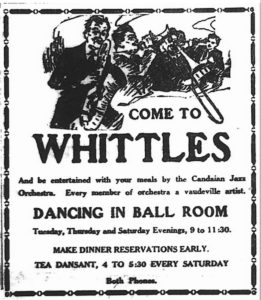

Ad for the Canadian Jazz Orchestra at Whittle Springs, Knoxville Journal, Dec. 21, 1919 (McClung Historical Collection)

And even more suddenly, everywhere was jazz music. A group called the Canadian Jazz Orchestra—the name is a puzzle, considering that at least one member was from Wilmington, NC—was in residency at Whittle Springs Hotel.

It was a permanently strange new era, for people–young people, mainly–who were ready for all this weird new stuff.

UT’s football team was rarely something to boast about. The new sport of basketball had caught on with both boys and girls. At least four local high schools had teams, and they all played games at the same court, the one at the YMCA, the transmogrified old Palace Hotel on Commerce Street.

The word “DANSANT,” most often capitalized, arrived on many sophisticated lips. Sometimes it was the biggest word in a hotel’s newspaper ad, as if it were all you really needed to know. Presumably more fashionable than a mere dance—perhaps an idea brought back by the troops returning from France–it was a new trend for hotels like the brand-new Farragut. Whereas string quartets had predominated in hotel ballrooms before, bands were getting bigger, and they were mainly horns, trumpets, trombones, saxophones. For people used to the gentler old ways, it was like a marching band had taken a wrong turn off Gay Street.

For the most part, though, Christmas of 1919 seemed muted compared to holidays past.

Stores had few surprises. Miller’s had a new toy reflecting an amenity of the skyscraper era, a miniature elevator with an electric motor. For almost 20 years, Asian-inspired fashions had been in vogue, and silk Japanese kimonos were near the top of the list. And speaking of vogues, the Arnstein, which always seemed a half-step ahead of Miller’s in keeping up with New York, advertised fashions seen in Vogue magazine.

Arnstein’s, still run by German-Jewish immigrant Max Arnstein, was mainly about fashions, but at Christmastime, the second floor was turned over to toys, especially dolls.

Woodruff’s offered tempting toys, velocipedes and roller skates, and chemistry sets, but also .22 rifles, listed alongside the rest of the toys. Pyrex was the amazing new glass cooking product, and available at Woodruff’s, too.

Automobiles tempted the affluent. Trying to adjust prices for inflation is problematic, but it’s worth noting that in 1919 a good new car was sometimes less expensive than a good piano. If you had about $1,500, you could buy either a fancy new car or a baby grand piano from any of several downtown stores.

The Gay Street Viaduct was still under construction, bottling up Knoxville’s favorite street, making it hard to reach from the Southern station, and bewildering to newcomers who hadn’t seen it before. Christmas week, they were connecting the viaduct to the elaborate Second Empire Southern office buildings on either side of Gay, putting new entrances on the second floors.

Passenger trains were at capacity, and not necessarily with people coming home for the holidays–many of the arrivals every December were East Tennesseans, and Eastern Kentuckians, Western North Carolinians, coming to Knoxville to get a hotel for a few days and shop. For thousands across the region, especially women, the trip to Knoxville was an annual ritual, part of the holiday season. If newspaper ads make downtown retail seem enormous, it was because it reached far beyond the approximately 80,000 people who actually lived in Knoxville at the time. In 1919, there were no chain discount stores, no Walmarts or Targets or Home Depots in the small towns and suburbs–there was just downtown Knoxville, which for almost half a million people across the region, was a dense wonderland of stores, Arnstein’s, Miller’s, S.H. George’s, Newcomer’s, Sterchi’s, each of them distinctly different and ever-changing.

Christmas of 1919 was assessed as the biggest shopping season in Knoxville history. It was, according to the Journal, “the most extravagant Christmas in history; a terrible carnival of spending!”

A lot of things were looking up for Knoxville. Sterchi’s was doubling the size and capacity of its Lonsdale furniture factory. UT was building a grand new building atop the Hill, to be named Ayres Hall, for the UT president who had died early that year, as it was being planned. The same year, a couple of immigrants from Greece, the Regas Brothers, opened their Ocean Cafe on Gay Street, where they offered a Sunday dinner of roast chicken, potatoes au gratin, and cream of oyster soup.

New subdivisions were popping up out in the country. Pilots were scouting national routes, and Knoxville was looking forward to the day, perhaps soon, that it would have its own airport. A field alongside the Whittle Springs golf course got the endorsement of one seasoned fighter pilot as a likely candidate.

The Dixie Highway was on its way, the national automobile road connecting Chicago and the upper Midwest to Florida, and coming right through Knoxville. Things were looking great, Knoxville boosters agreed. The head of the Chamber of Commerce predicted that based on trends of recent years, by 1930—just a decade in the future–Knoxville would be a city of a quarter million.

By 1919, there was more interest in movies than in vaudeville, and Staub’s Opera House, where Lily Langtry, Ethel Barrymore, Alla Nazimova, and W.C. Fields had performed, was making the big shift. Staub’s became the Lyric, a movie theater in the national Loew’s chain. The Bijou, across the street, still hosted a lot of vaudeville, like Pedrini’s Simian Actors—Paul Pedrini amazed crowds with what he could coax monkeys and baboons to do—along with pianist Huston Ray and “eccentric comedians” Prevost and Goelet. As well as something unusual, Col. John A. Pattee’s “Old Soldiers Fiddlers,” a Union veteran group from Michigan. They performed three shows daily, including Christmas, beginning at 3:00, the last at 9:15. The Bijou earned its motto, “The Joy Spot of Knoxville.”

But the biggest star in town that season performed in a church sanctuary. Billy Sunday himself, the Iowa-born former pro baseball star turned evangelist, gave a rousing Monday-morning sermon at First Methodist—then at Locust and Clinch—on Dec. 22. He denounced drinking and communism.

That morning, the streets in that southwestern quarter of downtown smelled of smoke.

~~~~~

Looking north of Gay Street with the Farragut Hotel visible three buildings in from the right, ca. 1919. (McClung Historical Collection)

In 1919, Knoxville’s classical and religious-music impresario was Frank Nelson, music director at St. John’s Episcopal. The eccentric multi-talented bachelor knew everybody, and was known for putting on impressive shows. On Sunday afternoon, Dec. 21, Nelson organized a fundraiser for the Empty Stocking Fund at the Bijou. The Empty Stocking Fund is a remarkably long-lived effort. In 1919, the Farragut Hotel featured a “gift window” where the latest donations to “friendless babies” were displayed.

The Sunday before Christmas, Nelson enlisted the best local talent to put on a fundraiser to remember, multi-part pageant of choirs, instrumentalists, coloratura sopranos, performing classic Christmas carols like “O Come All Ye Faithful” and “Hark the Herald Angels Sing”–along with several classical pieces for voice, piano, and violin.

That Empty Stocking benefit was likely the most difficult show of Frank Nelson’s long career. As his long-planned show was getting started, his favorite church, less than two blocks down Cumberland, was on fire. Rev. Walter Whitaker, who lived in the rectory next door, got word of it not long after he’d gotten home to have lunch with his wife. Whitaker’s name is known to students of literature because he was an early inspiration to a child he had baptized, James Agee. (The Agees had moved to Sewanee earlier that year, but may have been back in town for the holidays.)

St. John’s basement furnace had apparently overheated. The nave was full of smoke, and flames were coming through the floor. He called the Commerce Avenue Firehall, and as fire engines converged, volunteers hurried to carry out valuables. An unnamed black kid showed extraordinary bravery saving some priceless artifacts.

The restored nave inside St. John’s Episcopal Church after the 1919 fire, ca. 1921. (McClung Historical Collection)

It was a dangerous fire; stored in the basement handy to the furnace was 60 tons of coal. Firemen broke out four stained-glass windows, each a memorial to a well-remembered parishioner, including one to former rector Thomas Humes—to shoot 2,500 gallons of water a minute into the church. It was a nasty job, considering the cold weather. Before it was done late that night, black water was six feet deep in the basement.

Lost was Nelson’s Roosevelt pipe organ—the Roosevelt family was famous for producing organs before producing presidents—and the pews—and the interior murals painted by James Agee’s uncle, professional artist Hugh Tyler.

Remarkably, Frank Nelson’s Empty Stocking fundraiser at the Bijou, a few hundred feet down the sidewalk, was pronounced a success. For Nelson, it must have been a miracle of concentration. Some poor children, at least, would get some toys at Christmas.

The church among whose leadership was Gen. Lawrence Davis Tyson, soon to be elected to the U.S. Senate, had resources, and rebuilt quickly within its original stone exterior. Today, scorch marks from the 1919 fire are still visible deep within the church with the big red doors.

~~~~~

On Dec. 23, there was a shooting on Depot Street at the Dew Drop Inn—it wasn’t the first or last downtown attraction with that name–when a man described as “deformed” shot the proprietor, who he said attacked him during an argument.

On Christmas Eve, about 8 p.m., Patrolman J.J. Bowers was summoned to the intersection of University and Clinton (now College) to break up a fight between two black men. As he explained it, one of them, Bruce Lauderback, threatened him. Officer Bowers shot him in the chest.

That much sounds like an all-too modern story. But the story has a twisty ending. The bullet ricocheted off a rib and struck no vital organs. Lauderback was taken to Knoxville General Hospital, treated and released less than two hours later. Swearing revenge, Lauderback swore he would kill Officer Bowers.

As he became subject of a manhunt, it was discovered that Lauderback had been accused of shooting at officers back in 1911, and had himself been shot by officers once before, in 1916. Lauderback was captured in early 1920, after allegedly participating in an armed robbery. He got out of prison to survive one more shooting, this time by a cousin.

However, Louderback apparently never fulfilled his pledge to kill Officer Bowers, who died of a stroke a few months after their Christmas Eve altercation.

“In former years, numerous cases of intoxication came under the observation of members of the police department, but at a late hour last night, only a few men had been arrested on charges of drunkenness and disorderly conduct,” assessed the Journal. “In districts where the Negroes congregate for socials, the usual crowds were expected, and there was an absence of disorder.”

All in all, the police department reported, it was a silent night.