East Tennessee Marble Industry

“Marble Industry of East Tennessee, 1850-1963

by Dr. Susan Knowles

In 2016-2017, Dr. Susan Knowles served as the guest curator for “Rock of Ages” an exhibition hosted by the East Tennessee Historical Society detailing the history of the East Tennessee Marble Industry. The above weblink features an overview of the exhibit and an interview with Dr. Knowles.

Selected extracts from Dr. Knowles’ successful, multiple property nomination to the National Register of Historic Places:

The first published mentions of marble in East Tennessee began in the late 1810s as natural scientists, itinerant ministers, and travelers through what was then considered the backcountry of southwest Virginia, western North Carolina, and the eastern sections of Tennessee and Kentucky began to note the presence of marble in Tennessee. Their accounts appeared in such publications as the American Journal of Science and attracted national attention to what would become, by the 1880s, one of Tennessee’s best-known natural resources.

Yet some of East Tennessee’s prominent early citizens certainly had seen possibilities for using the native stone. Francis Alexander Ramsey’s 1797 home, Swan Pond, now known as Ramsey House, is located just east of the confluence of the Holston and French Broad rivers, which form the Tennessee River northeast of Knoxville. This imposing, two-story Federal style house is one of the earliest known examples of the use of Tennessee marble as a dimensional stone. Ramsey’s slaves may have worked alongside master mason Seth Smith, or at the behest of house designer Thomas Hope, on the contrasting blue stone quoining and coursework and hewn pink marble blocks of Ramsey’s impressive home place.

John Sevier’s Marble Springs, a circa 1800 homestead, was more than likely a log structure but its name was derived from the deposits of marble in the nearby Neubert Springs area, which is in the vicinity of Bays Mountain. An 1814 journal entry reveals that Sevier carried a marble sample to the U.S. Capitol to show to one of the Italian master carvers.

The author of an anonymous pamphlet published circa 1890 and entitled Fifty Facts and a Few Figures Concerning Knoxville, Tennessee “The Marble City”, asserted that marble had been quarried in Knoxville since 1842. Yet without specific confirmation to verify such an early date for commercial quarrying in Knoxville, we should more likely date the beginnings of the industry in Knox County to about 1850.

Many enterprising Knoxville residents were no doubt aware of the potential value of the local marble veins. On an 1851 visit to Washington, D.C. in the company of the politically well-connected Oliver Perry Temple, Robert H. Armstrong, son of prominent Knoxville citizen Drury P. Armstrong, made a point of visiting the Washington National Monument, then under construction:

“I visited the monument alone—and spent more than half a day about it…had attained the height of 90 feet … made of huge blocks of whitish marble quarried on the Potomac—of a chrystalization [sic] larger and coarser than any I have ever seen. The work was going on well—a stationary engine drawing up men, materials and everything necessary. I was conducted to the blocks contributed by the several states formed of specimens of the native marble or rock of each. I was much interested in these blocks. There were also many contributed by Societies and corporations. All bore appropriate and patriotic mottoes and inscriptions, with devices &c &c. The largest block was one of granite from Massachusetts—but the prettiest I thought was that of the state of New York. It was black and beautifully sculptured in bas-relief. The blocks from Tennessee were beautiful, favorably comparing with any of the collection—but I know of marble in the state far more beautiful than any of the specimens in the whole number.”

James Safford, in his first geological report (1855) referred to Col. John Williams, a prominent Knoxville citizen and former U.S. Senator who commanded a troop of Tennessee militia during the War of 1812, as having a “fine and valuable quarry of gray marble” a few miles east of Knoxville, which was part of a massive bed of marble 375 feet thick containing 95 feet of white marble near its base. Safford stated: “several marble factories in Knoxville have worked it”. He also mentions an exposed marble bluff on the French Broad, five miles north of Knoxville at Mecklenburg, the home of Dr. J.G.M. Ramsey.

The small town of Concord, strategically located on the ET&G railroad line just west of Knoxville, and adjacent to the river, developed quickly into a center of marble production and transport after the railroad was completed. By the 1870s, Concord boasted a two-story brick Masonic Lodge and several substantial brick businesses and homes. By 1883, there were four marble businesses and a marble mill active in Concord. Two families of stonemasons relocated from the Rogersville area to Concord and set up successful stone carving business.

Hal Glaspey Winfrey, whose father, Holmes Warren Winfrey, was a millwright, moved with his wife Nannie Moore Fawbush and several brothers to Concord in 1886. Hal was there to “take advantage of work in one of the four new marble quarries”, while his brother, the Reverend William Winfrey, became the first minister at Concord Baptist Church. James Farmer Woods, Jr., a prominent quarry operator in Concord, was extracting marble from quarries located on Callaway Ridge by the 1890s and operating a marble saw mill circa 1900. J.F. Woods & Company, Manufacturers and Dealers, advertised their expertise in monumental work and fine carving. Woods and a man named William Scales obtained a patent on a stone-channeling machine in 1891.

In the 1870s, railroad men like Thomas A. Scott, of the Pennsylvania Railroad, began to buy some of the failing southern lines and consolidate existing roads into the kind of powerful network needed to revive the Southern economy. The business acumen of his secretary, Andrew Carnegie, proved instrumental in creating a profitable system for freight shipments. With the economic crisis of 1873, a number of lines did not survive. Even Scott’s powerful syndicate, the Southern Railway Security Company, had to trim its holdings. For a brief period, it had helped sustain the newly integrated East Tennessee & Georgia (ET & G) and East Tennessee & Virginia (ETV&G) Railroad and the mainstay Richmond & Danville Railroads, as well as feeder lines serving North Carolina, and Georgia as far south as Atlanta.

As Knoxville’s reputation as a marble center began to grow, one native son seems not to have noticed. In a memoir written soon after the Civil War, Francis Alexander Ramsey’s son, the historian James Gettys McReady (J.G.M.) Ramsey, described the house he grew up in as having been constructed of pink granite with blue limestone corners, arches, and chimney. Perhaps he was unfamiliar with the geological reports of Troost and Safford, neither of whom identified granite anywhere in Tennessee. Nonetheless, it seems curious that Ramsey mistook the dark pink marble, which was quarried close by his boyhood home on Thorngrove Pike, near the Forks of the River, for granite.

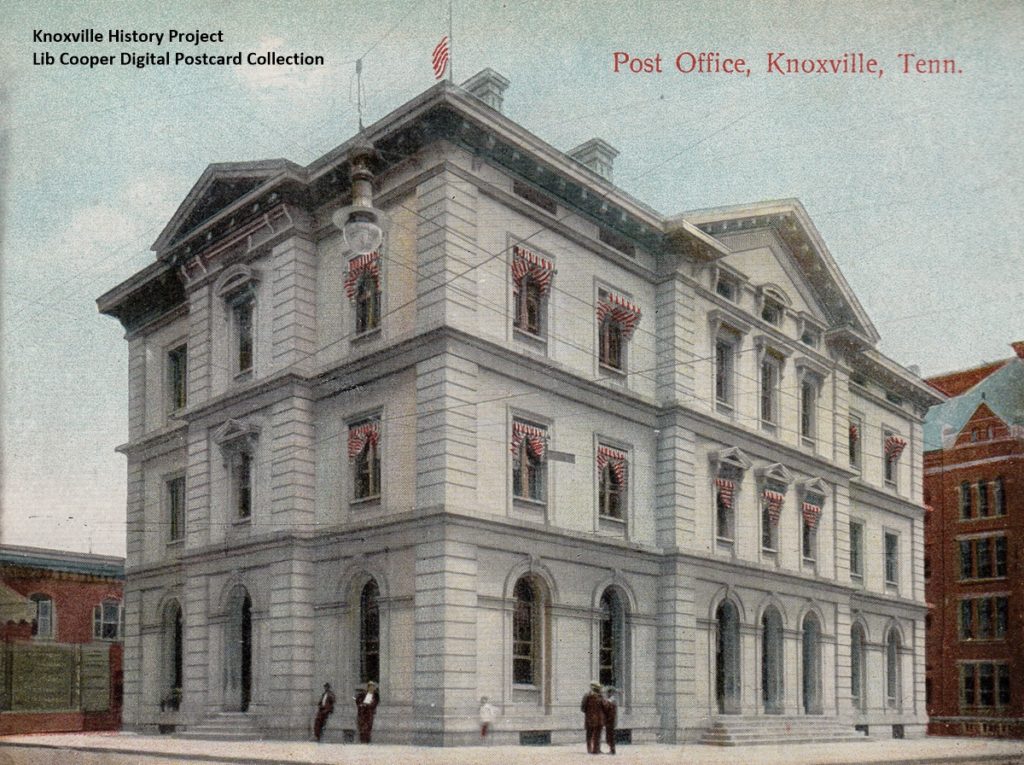

One of the quarries not far from the Lebanon-in-the-Fork Presbyterian Church (not extant) that J.G.M. Ramsey’s father, Francis Alexander Ramsey, founded in the Forks of the River district would soon be chosen as the source of marble for the new Knoxville Custom House. This substantial marble edifice, erected 1871-74, was the first federal building project to come to the state, and one that would open the way for the use of East Tennessee marble in future federal projects. Architect Alfred B. Mullett, working for the Treasury division, designed the new building to function as both customs house and post office, and also provide office space for other federal agents in East Tennessee.

U.S. Customs House and Post Office completed in 1874. Lib Cooper Knoxville Digital Postcard Collection.

Several of the men who worked on the Custom House project would continue in the marble business. Paymaster George W. Ross, in partnership with William Patrick, James Patrick, and J.H. Holman, formed the Knoxville Marble Company in 1873. Ross and Patrick arranged to lease a quarry adjacent to the Lebanon-in-the-Fork Presbyterian Church (not extant) to provide marble for the St. Louis Custom House, designed by the same architect, which was erected soon after the Knoxville building. In Introduction to the Resources of Tennessee (1874), Joseph Buckner Killebrew, Tennessee’s Commissioner of Agriculture, Statistics and Mines, 1871-81, and State Geologist James Safford reported that the quarry at the Forks of the River, which had originally been opened for the purpose of supplying the Custom House in Knoxville in 1871, was now being run by W. Patrick & Company. Employing thirty people, they were using the “most modern methods” for sawing slabs in the quarry using steam power to run two engines: one for sawing and one for derrick work. This operation was close enough to the riverbank that slabs were easily transferred from the mill to flatboats for the four-mile trip down the river to the railroad for shipping.

Harmon Kreis*, a Swiss Immigrant and young Union veteran, who worked as a timekeeper for Ross and Patrick at the Knoxville Marble Company later went into the quarry business for himself. With partners T.S. Godfrey and W.R. Monday, he developed several quarries in the same vicinity, including Gray Knox, American Marble, and Gray Eagle. With Thomas Deane, he was a founding officer of the Appalachian Marble Company.

Two of George Ross’s sons went into the marble business. John M. Ross became President of the Knoxville Marble Company upon his father’s death. After the Knoxville Marble Company sold its holdings in the Forks of the River area to Evans Marble Company, John M. Ross acquired marble holdings for the company in South Knoxville, almost directly across the French Broad from the Forks area, which he parlayed into several successful businesses, including a mill and quarry operation in the vicinity of Island Home, which he sold to the Republic Marble Company, and a quarry that he continued to work near the site of his first quarry. After the sale of Ross’s first quarry property to the Republic Marble Company, which had quarry operations in Concord, and in Union County near Luttrell, the company styled itself the Ross and Republic Marble Company. The quarry they operated in the vicinity of Island Home soon became known as the Mead Quarry, after company president, Frank S. Mead. The nearby quarry belonging to John Ross was commonly referred to as the Ross Quarry.

* Related story: One of marble carver Albert Milani’s most unusual commissions, a memorial to Knoxville-born racing car driver, Albert Jacob “Pete” Kreis, can be found nearby at Asbury Cemetery in East Knox County. Pete Kreis (grandson to Harmon Kreis) was killed on a practice lap at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1934. The sculpture was recognized as the Most Outstanding Memorial by the New York Times.

Selected Sources/further information:

Charles Faulkner, The Ramseys at Swan Pond (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008.

Carroll Van West, “Marble Springs,” in Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.

Weblinks to Dr. Knowles’ successful nominations to the National Register of Historic Places:

Marble Industry of East Tennessee, Ca. 1838-1963: Multiple Property Nomination

National Register of Historic Places: Mead Marble Quarry

National Register of Historic Places: Ross Marble Quarry