Earl O. Henry

Bird Calls and Baking Soda: The Life and Legacy of Earl O. Henry

Earl O’Dell Henry, a Knoxvillian, was a dentist, taxidermist, artist, and an active member of the local East Tennessee Ornithological Society (a club that still exists today). Earl Henry’s passion and dedication to nature and art are his greatest legacy. However, on a tragic note, Henry lost his life on the USS Indianapolis in the Pacific theater at the tail-end of World War II, in what has been considered one of the worst naval tragedies in U.S. Maritime history.

As a youngster at the turn of the last century, young Earl became enthralled by birds and spent the rest of his life learning their names, studying them in the wild and subsequently capturing their spirit through paintings and preparing specimens.

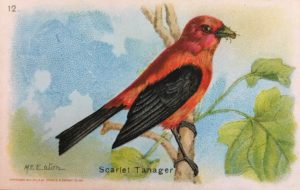

Born in 1911, Earl, like many like-minded naturalists of that era became fascinated with birds after collecting the small, colorful, cards found in Arm & Hammer Baking Soda boxes. Earl’s grandmother shooed him out of the kitchen and encouraged the 12-year-old lad and his friends to go out and see if they could identify any of the birds on the cards. From such beginnings, a life trajectory was set. For young Earl would develop a deep love for his avian friends that would last all of his life.

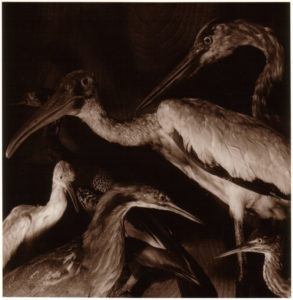

As a young man, Earl Henry became a member of the East Tennessee Ornithological Society in Knoxville and it is believed he was a protégé of Harry Ijams. Certainly, Ijams and other father figures in the club nurtured his burgeoning interest in bird study as well as the art of taxidermy. During those days, most self-taught ornithologists increased their knowledge of the birding world by keen observation as well as by preparing study skins and mounted specimens. Earl’s initial efforts were augmented by a correspondence course but it took perseverance to begin capturing natural and elegant poses on mounted plinths. In time, Earl became an accomplished taxidermist but after he became a dentist he worried that his patients might not enjoy the notion of him handling dead birds. He began to paint birds, beginning with waterfowl, and discovered he had found a new passion.

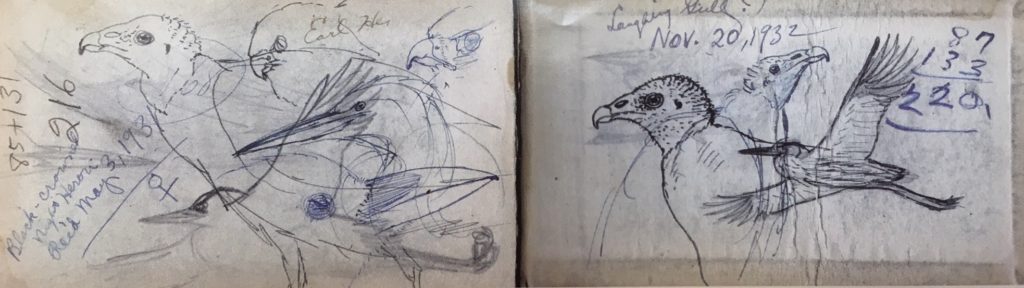

Earl Henry was a well-rounded naturalist who traveled extensively across Tennessee and other states throughout the Southeast. His old bird guides are full of his notations, detailing when and where he saw each species. The guides were lovingly annotated with charming illustrations of birds he witnessed, often enhancing the static depictions of birds printed within the pages. Earl’s talent was developing rapidly but this precious life, like so many others around the world, was cruelly cut short by war long before his time.

Earl Henry’s sketches. (Courtesy of Earl Henry Jr.)

In 1942, Henry joined the U.S. Navy and served on active duty, initially at the Naval Hospital Parris Island in South Carolina. It was here that he honed his artistic ability using tempera paints on boards. His paintings of the Blue Jay, Cedar Waxwing, Orchard Oriole and the Painted Bunting are similar in style – posed males and females of each species in the Audubon mold, while others such as the Barn Swallow and Red-winged Blackbird featured evocative background landscapes providing a richer and more sophisticated natural setting. He later painted many more birds while stationed at the naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

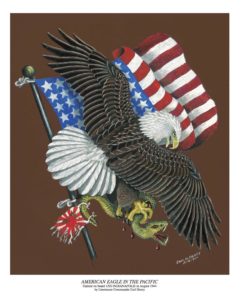

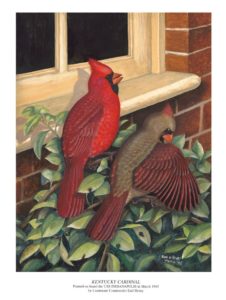

Henry was assigned to the Navy cruiser, the USS Indianapolis in 1944 as on-board dentist while supporting the war effort in the South Pacific. On ship he found a way to educate and entertain his fellow officers by sketching birds on chalkboard and enthralling the crew while imitating bird calls he had learned back home in Tennessee. It is no wonder he was called “The Bird Guy” by the crew. Aboard the USS Indianapolis, Lt. Commander Henry painted his most famous works, notably the “Kentucky Cardinal” and the “American Eagle in the Pacific.”

However, on June 30, 1945, tragedy struck the USS Indianapolis; the ship was torpedoed twice by a Japanese submarine while making its return journey after delivering parts of the atomic bombs, used in the coming days to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A total of 880 men perished with the ship while only 216 survived. Lt. Commander Henry perished that day with the ship and died at the age of 33.

Just before the ship went down, Lt. Henry had spent three weeks on leave back in the United States. His wife, Jane Covington Henry, was pregnant and expected to give birth several weeks after her husband returned to the war front. Yet, two days after Henry left Memphis, his wife gave birth early to their only child, Earl Henry Jr. Like so many other wives left behind, Jane was left a widow to care for her son who would never meet his father.

Throughout his life, Earl Jr. certainly has developed a lifelong connection with his father and feels blessed that his father left behind so many works of art. In addition to paintings and mounted birds, he treasures the collection of letters written by his father to his mother while he was at sea. Plus, he owns a vinyl record, now digitized, of his father’s imitations of bird calls recorded in the home of a foreign language professor at the U.S. Naval Academy in January, 1944.

Several of these audio recordings can be heard at Ijams Nature Center in Knoxville on the Earl O. Henry Birding Trail. Along with a series of interpretive signs conveying Dr. Henry’s story, the hand-cranked audio boxes each contain four native bird calls followed by Henry’s vocalizations of the same species. Ijams Nature Center installed the trail experience in 2014 to convey the Earl Henry story as well as to encourage visitors to learn about native bird species such as the Carolina Wren, Red-Eyed Vireo and Northern Flicker, and to recognize their calls out in the woods.

The interpretive trail can be found on the Discovery Trail on the oldest part of the Ijams property which started out as the Ijams Bird Sanctuary during the 1920s. Dr. Henry would have been familiar with the landscape after spending time there as a young man as a member of the East Tennessee Ornithological Society, which conducted spring and fall bird censuses there ever year.

The interpretive trail can be found on the Discovery Trail on the oldest part of the Ijams property which started out as the Ijams Bird Sanctuary during the 1920s. Dr. Henry would have been familiar with the landscape after spending time there as a young man as a member of the East Tennessee Ornithological Society, which conducted spring and fall bird censuses there ever year.

Henry served as secretary-treasurer for ETOS in 1930 and left his mark by decorating the minutes with bird illustrations. He also served as vice president in 1936 and president the following year. In 1940, the state organization chose to showcase his artistry by employing four of his bird illustrations on the cover of the quarterly journal The Migrant throughout the 25th anniversary year.

Earl O. Henry Interpretive Birding Trail at Ijams Nature Center.

The Ijams visitor center also showcases Ear Henry’s life and legacy as well as a selection of mounted birds. The collection was originally given to Ijams when its visitor center opened in 1997. Earl Henry Jr. was there at the building’s dedication to talk to visitors about the collection and memorably shone a light into his father’s hummingbird nest to illuminate it. On display now are fine examples of Henry’s taxidermy including selections such as Baltimore Oriole, Migrant Shrike, Chimney Swift, Yellow-breasted Chat, and a King Rail originally found in the Fountain City area of Knoxville. In addition to the mounted birds are examples of the Migrant covers, Arm & Hammer cards, personal artifacts and special documents as well as examples of Henry’s artwork.

Earl Henry Jr. also keeps the enduring story of his father’s artistry and that of the USS Indianapolis alive by giving talks throughout Tennessee and beyond at special USS Indianapolis events. The sinking of the USS Indianapolis is a national touchstone and Lt. Henry is perhaps one of the most widely known of all the men who died aboard the ship. The USS Indianapolis Memorial Museum also features an exhibit on Lt. Henry in the ship’s namesake town, Indianapolis Indiana.

The life and legacy of Earl Henry lives on in other ways. Each year, since 1946, the Second Dental District in Knoxville has held an annual meeting in Dr. Henry’s memory. Plus, Earl Henry Jr.’s production of high quality prints and notecards of his father’s work continue to be popular throughout the state and online:

To see and order Earl Henry’s bird prints online, visit: https://www.earlhenrybirdprints.com/

The above story is an edited version written by Paul James which originally appeared in the Tennessee Conservationist magazine in November, 2015.