Island Home

Island Home Park

Island Home Park is a distinct residential community located in South Knoxville, the broader neighborhood is known as “Island Home.” Distinguished by 1909 marble entrance pillars at the intersections of Island Home Avenue at Maplewood Drive adjacent to the Tennessee River, and newer ones at Island Home Avenue and Fisher Place, Island Home Park is notable for its many Craftsman bungalows originally built in the 1910s and ‘20s. The community is bordered by the Tennessee River on the north, the Tennessee School for the Deaf campus on the east and the Gulf & Ohio railroad and Island Home Avenue on the south.

Island Home Park is a distinct residential community located in South Knoxville, the broader neighborhood is known as “Island Home.” Distinguished by 1909 marble entrance pillars at the intersections of Island Home Avenue at Maplewood Drive adjacent to the Tennessee River, and newer ones at Island Home Avenue and Fisher Place, Island Home Park is notable for its many Craftsman bungalows originally built in the 1910s and ‘20s. The community is bordered by the Tennessee River on the north, the Tennessee School for the Deaf campus on the east and the Gulf & Ohio railroad and Island Home Avenue on the south.

Island Home Park contains approximately 200 homes and lies 2.5 miles from downtown Knoxville. For many years it remained relatively close yet detached from downtown, buffeted by the stagnant post-industrial corridor along Sevier Avenue.

Major developments beginning around 2005 with the growth of Ijams Nature Center, the creation of the Urban Wilderness trails, and new business investments around time of the completion of Suttree Landing Park in 2016 began changing the community dynamics around Island Home Park. New student apartments, restaurants, bars, coffee shops, and other retail establishments, all contributing to South Knoxville’s new and hip “SoKno” moniker, have not only made Island Home Park more desirable as a location, and increasingly more exclusive, but also have connected the subdivision more closely with its broader neighborhood. Yet, there is a distinct history here.

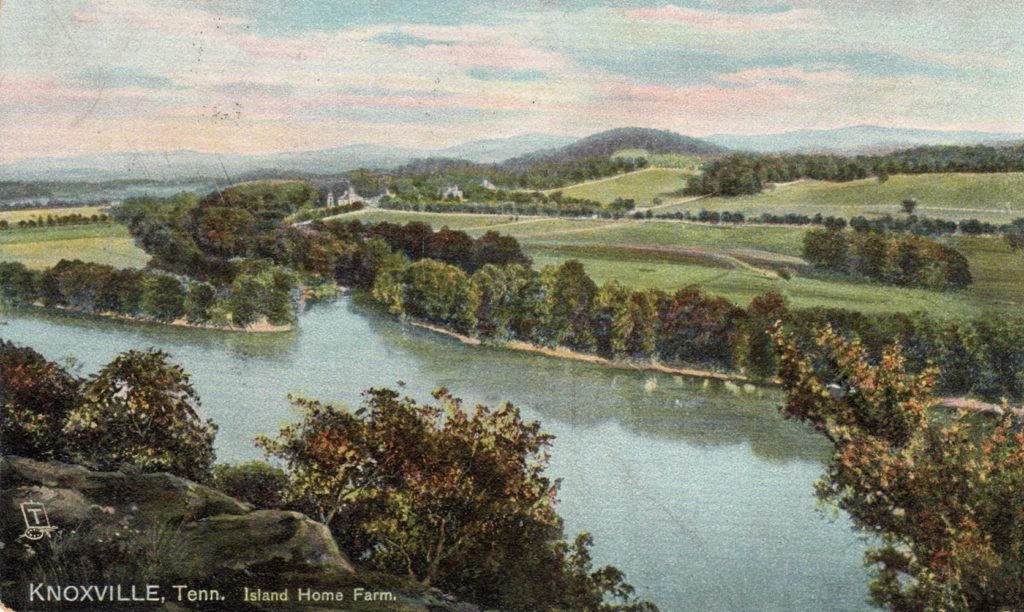

Early 1900s postcard. (Courtesy of Paul James)

In the early 1800s, Moses White, son of the city’s founder James White, owned this area including a small Island in the river downstream from the city of Knoxville, later known as “Williams Island” after the subsequent owner who then sold much of the land to Perez Dickinson, whose legacy still infuses the landscape.

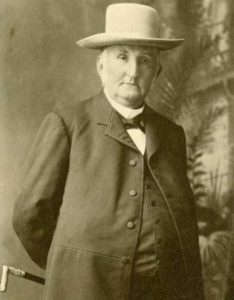

Perez Dickinson, 1813-1901 (Courtesy of McClung Historical Collection.)

A wealthy Massachusetts merchant and banker, and cousin of poet Dickinson, Perez Dickinson moved to Knoxville in 1829 where his brother, Joseph Estabrook, was the principal of the Knoxville Female Academy, and later became the President of East Tennessee College (now UT). Dickinson himself served as principal of the Hampden Sidney School in Knoxville before studying at East Tennessee College. After graduation his educational career deviated into a business partnership with James Cowan leading to the formation of an enduring grocery and dry goods wholesale business, Cowan, McClung, and Dickinson. Dickinson also served as President of First National Bank, and according to French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County Tennessee (East Tennessee Historical Society, 1946) “its stockholders were always paid in gold as long as Dickinson was President.”

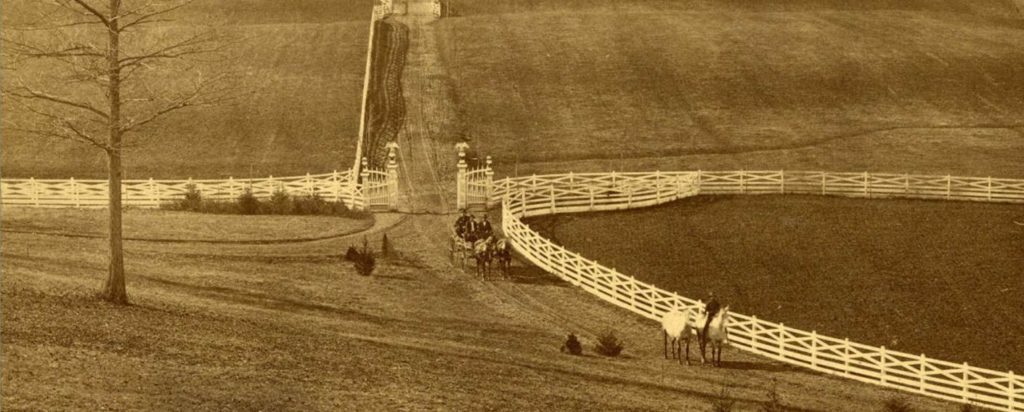

Perez Dickinson’s Island Home Estate looking west, circa 1890s. (Courtesy McClung Historical Collection)

Yet, it was Dickinson’s experimental Island Home farm that largely defined this section of the South Knoxville landscape. 600-acres in this vicinity were purchased from Col. Thomas Williams in 1869 and a 200-acre parcel, lined with white fencing, formed Dickinson’s experimental “model stock farm.”

The Perez Dickinson Italianate mansion (which he supposedly never once spent the night in) was built during the 1870s for his new wife, Susan Penniman, who died before it was completed, featured formal gardens surrounded by rolling hills and a long driveway leading to the estate’s front gate topped with eagle finials. Dickinson was known to regularly host social gatherings especially for the community.

Perez Dickinson mansion and formal gardens, 1887. (Courtesy McClung Historical Collection)

Following Dickinson’s death in 1901, ownership of the farm passed to his son, Perez Dickinson Cowan. The property changed hands several more times and by 1911 the newly formed Island Home Park Company acquired a 117-acre tract immediately west of the farm gates. The subdivision was subsequently laid out with utilities and hopes that connections with the nearby trolley line were realized in 1912, at least to the community’s entrance. The main street was Knoxville’s first designated Boulevard and named as such – Island Home Boulevard. The community association’s self-penned history describes those early years:

“The columns and the house at the entrance to Island Home Park, possibly a show house, were built in 1909. The first lot sold in the new Island Home Park subdivision in May 1911 was on Island Home Avenue. Sales followed in 1912 for lots on Maple Avenue (now Maplewood), Harvey Heights (now Hillsboro Heights), and Island Home Boulevard. The young neighborhood developed at a rapid pace. A 1922 map includes 44 houses. Development continued through the 1920s and later.”

The Tennessee School for the Deaf deserves a mention. In 1924, the school moved from its downtown location (previously established as the state Deaf and Dumb Asylum in 1844) to a new campus laid out by Nashville-architect Thomas Marr, an alumnus of both TSD and the prominent Gallaudet Deaf School in Washington, D.C. The Perez Dickinson house, located within the school campus, serves as the superintendent residence. Several of the older buildings date to the 1920s, including the restored gymnasium, originally constructed in 1928.

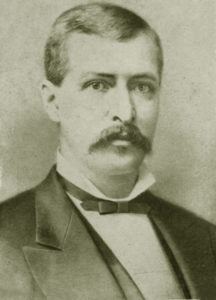

Joseph Ijams, Superintendent of the Deaf and Dumb Asylum, 1866-1882. (Courtesy Tennessee School for the Deaf)

The school itself has an unexpected connection with its eastern neighbor, Ijams Nature Center. Also once part of Perez Dickinson’s estate, the nature center’s original 25-acres formed the family farm established in 1910 by Harry and Alice Ijams. Harry’s father was the nationally-lauded superintendent hired by school trustees in 1866 to bring back the Deaf and Dumb Asylum (as the school was originally named from 1844-1924) to prominence after the Civil War, when it was used as a military hospital. Joseph Ijams served until 1882 when he died unexpectedly after a short illness.

Some notable residents have lived in Island Home Park including Arthur Morgan the first chairman of Tennessee Valley Authority who lived here during the planning and construction of Norris Dam.

Paul Y. Anderson grew up here before winning the Pulitzer Prize for his investigative journalism. His burial is marked by an interesting memorial at the nearby Island Home Baptist Church.

Tony-winning actor and TV star John Cullum, also grew up here.

Thanks to Nancy Campbell for sharing Island Home Park Association history with KHP.