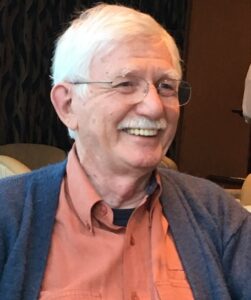

Growing Up in Knoxville by Gerald R North

This essay is modified from a chapter from the book, “The Rise of Climate Science, A Memoir by Gerald R. North,” to be published by Texas A&M University Press October, 2020.

I was born in the little town of Sweetwater, Tennessee, on June 28, 1938. My father Paul “Sanford” North was an auto mechanic at the Chevrolet dealership there. Soon we moved to Statesboro, Georgia, where he was in charge of the repair department at the dealership. At some point it became clear that WWII was ginning up and America would be drawn in. Sanford expected to be drafted any day. In the early 1940s we moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he was in charge of the shop at Reeder Chevrolet. The purpose of the move was to bring us closer to my mother’s family who were situated in and around Knoxville. In particular, my mother’s father, Green Lee Hill, her stepmother, Jeanette, older brothers Clarence Hill, Jefferson “Glenn” Hill and his wife Jean lived all lived in Knoxville area. She also had a younger half sister, Edith, half brother, Kenneth Hill, who was drafted into the army and served in the Normandy Landing in France in 1944.

Some Geneaology

My genetic heritage is a combination of Scotch-Irish and English and a little German families from the Tennessee Valley and Southern Appalachian Mountains. On my father’s side, I actually have some brief Texas roots (I live in College Station, Texas now). Like Sam Houston, I was born in East Tennessee, but made it eventually to Texas. My great grandfather Porter North was born in East Tennessee probably of Scotch-Irish ancestry. He married a German American girl, family name Hammer, from Dandridge and they moved to Gainesville, Texas just south of the Oklahoma border in East Texas. This town was the site of a lynching of dozens of mainly northern sympathizers during the Civil War. My grandfather Jerome North was born in Gainesville, TX, in 1877. The family apparently moved back to upper East Tennessee soon after Jerome’s birth. The North family had a modest farm in the very fertile Tennessee Valley bounded on east and west by mountain ranges. I would classify these as lower middle-class Republicans and they stayed with that party through Jerome’s lifetime, and beyond except for my rebellious father who was a (Roosevelt) Democrat. East Tennessee was mostly sympathetic to the Union during the Civil War. The lack of a slave economy may partly explain this leaning in both East Tennessee and Western North Carolina.

I know a bit more about my mother’s lineage. Her maiden name was Hill. The Hills (at least one thread) can be traced back to London in the 1700s. They came first to Virginia and then into western North Carolina, probably surviving as indentured servants (a large fraction of whom died before fulfilling their debt and being freed). One of my great-great grandfathers, Green Berry Payne, who in some accounts might have been a Czech, although the name does not read like it. Sounds more like a Native American to me (but my DNA did not show NA genes). Another great-great grandfather was Elijah Decatur Hill. I have seen their burial sites in a graveyard inside the Great Smoky Mountain National Park. Stories have it that both fought in the Civil War on the Rebel side, but at least one of them was captured and fought on the Yankee side until he escaped and hid in a hole in the ground. My guess is that they did not want to be ripped from their mountain home where slaves were not an issue. The story recalls the novel and movie “Cold Mountain.”

After a meeting about twenty years ago in Asheville I dragged a colleague, Sam Shen, along on an adventure. In order visit the cemetery we had to cross along the top of the Fontana Dam and turn right along the lake’s edge on a dirt road to its end, then left a few hundred yards. We benefitted from information from the gentlemen at the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) office atop the dam. There was a marker slightly overgrown with vines that indicated the trail. You park and hike up a steep path. One of my uncles Ross Hill is buried there. He died as a child, having been poisoned by some ink his prankster pals dared him to drink. Several other great uncles and aunts are also in the same cemetery, known as the Payne Cemetery.

For a time the family moved to a town called Calderwood, Tennessee, located on the Little Tennessee River where several dams sit downstream from the Fontana. My Grandfather, and patriarch, Green Lee Hill (obviously named after his maternal grandfather, Green Berry Payne) worked as a foreman on some of those dams in the 1930s as part of the TVA. Not surprisingly, he was a Roosevelt Democrat. See the (1960) Elia Kazan film “Wild River” with Montgomery Clift and Lee Remick

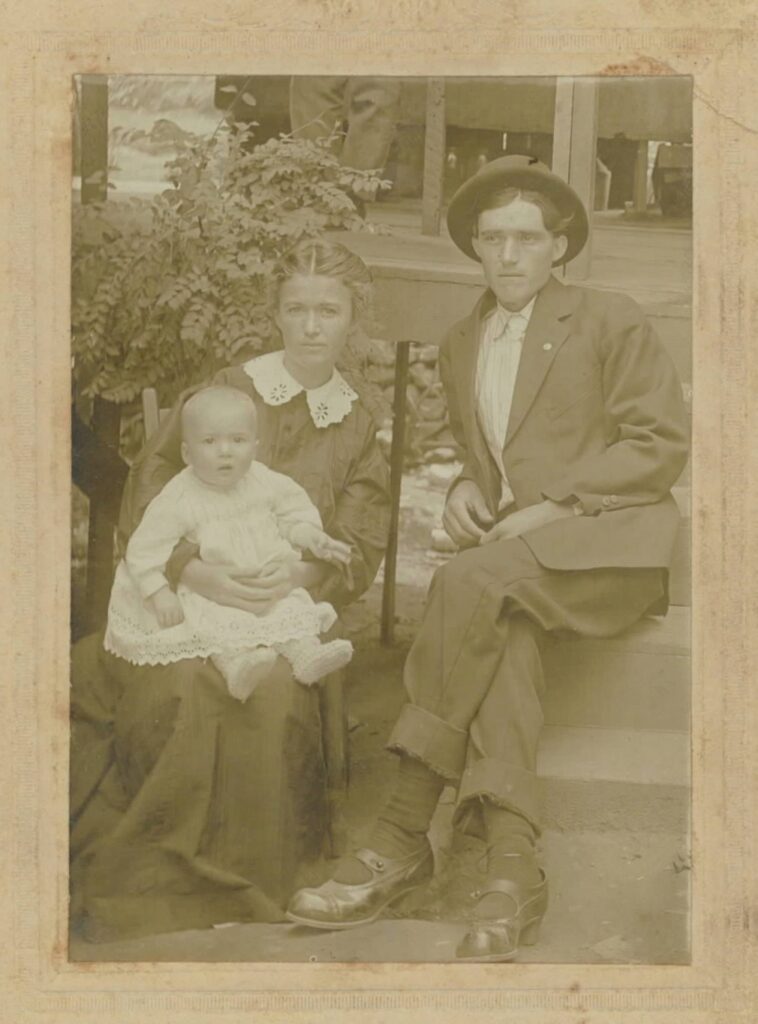

My maternal grandmother died of consumption when my mother was only nine months old. Her maiden name was Webster. One of her sons said that her father was called “Professor Webster,” but I have never been able to find out about the “professor,” which probably indicated that he was school principal in a private schoolhouse.

Green Lee Hill and his wife Birdie Webster Hill, Marjorie’s Mother. The child is one of her older brothers. (Gerald R. North)

Originating in northeast Georgia, then into North Carolina, the Little Tennessee River is a beautiful pristine stream eventually turning around the high peaks in the Smokies on the south side and into the state of Tennessee near Tellico Plains. There it flows into the larger Tennessee River so prominent on maps as it flows south into Alabama and back up through Tennessee again and into Kentucky finally emptying into the Ohio River. The rivers in the Tennessee and North Carolina mountains were subject to downpours and subsequent catastrophic floods. After inserting dams on the rivers by TVA, copious electricity could be generated. The result was not only flood safety, but the opening of such industries as Alcoa Aluminum, and later the giant defense installation at Oak Ridge, where I was destined to work during my college years. My grandfather once took me trout fishing in the mighty wild Tellico Plains area.

Green Lee Hill (upper center) and his siblings. Upper Left, Ella, Front row: Dell, Jeff, Cindy, and Decatur (note the shoe off). (Gerald R. North)

The Hill family bobbed up and down from lower class hillbillies to lower middle class ranks over the years, living in various towns in the mountains of the two neighboring states. My Uncle Clarence (Marjorie’s brother) lived on a hard-scrabble farm in a valley called “Red Holler.” He told me of the miseries of the Great Depression where he as a young man trucked vegetables into Knoxville’s Market Square, and unable to sell any of his produce, they took the sad trips back home to the farm.

Green Lee became a foreman in the coalmines in the region. His son Clarence was spared from the draft in WWII because of his ears being damaged from a coalmining explosion. Clarence taught me how to throw a curve ball. He had been a pretty good pitcher at some point. After the war he packed up his family of five kids, Aunt Maye and moved to the Detroit area where he was a mechanic, repairing forklifts and other small machines, for Chrysler Corporation until his retirement. He became a shop steward and his only son among four daughters, C. W. (‘Dub’) also took up the same track and became a labor leader.

My Uncle Kenneth Hill, Marjorie’s half-brother, was a construction worker who worked jobs all over East Tennessee – I remember most at Oak Ridge. He had three boys. He collapsed while at work in Oak Ridge with a brain tumor. It had originated from prostate cancer, and he died at about age 60. His boys made it into the middle class and two of them eventually received college degrees. One of them told me some of this genealogy years ago. The third son got into the custodial business in New York City. I lost track of him.

Kenneth’s sister Edith Scott was one of my favorites. Her mother (and Kenneth’s), Jeanette married Green Lee, after Marjorie’s mother’s passing. Green Lee’s mother, Harriet, who was the daughter of Green Payne, raised my mother, Marjorie. So we were close to my great-grandmother, Harriet, who lived to be 103 or 99, depending on the source. Harriet lived in a tiny cabin just as it was as she grew up: outhouse, spring water, coal stove, newspapers glued on the wall for wallpaper. She lived with her retarded son Pless, until he died at about age 55. I remember that she crocheted dishcloths, webbed with a colored border. My mother always brought more thread when we visited her to supply this activity. My mother had drawers filled with these dishcloths (called dish rags). When she began to run out of storage space, she distributed them to friends. It kept Granny busy and useful until her eyes finally gave way.

Clarence and Glenn were full brothers of Marjorie and they were special to me. This was especially because Glenn had no children and Clarence had four girls before his son, was born. The latter grew up in Warren, Michigan, after the family migrated. Clarence died in his mid-seventies from prostate cancer and Glenn at age 55 from throat cancer. They enjoyed far too much alcohol and tobacco for long life.

War Time

My mother, Marjorie, and my father met when she worked in the ticket booth at the Roxy Movie Theater on Union Avenue near Market Square in Knoxville, where the farmers brought their produce for sale off their truck beds. They married in 1934 when my mother was about 17. My dad, Sanford, and Uncle Glenn were buddies and were totally consumed with automobiles and motorcycles in their youth. I think they once attended the Indianapolis 500, possibly on their motorcycles. Both were probably heavy drinkers as young men. Glenn had a terrible car wreck before the war in which some of his scalp was burned along with a part of one ear and a piece of one eyebrow. Even with the scarring he was a handsome and wonderfully affable man.

Glenn and Jean had no children and this circumstance might have caused him to be drafted into the US Navy before my father. He served as a gunner on the USS Raymond, a destroyer escort (DE-341, see numerous websites). In 1943 he saw action at Guadalcanal, the Battle of Samar and later his ship served as escort at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

My mother’s Father, Green Lee Hill was a friend of Benjamin Joffe and his Jewish family. Ben — to us ‘Pop’ Joffe – owned a dry goods store (the Dixie Store) on Central Street just a block or two off Gay Street, the main business street in downtown Knoxville. Market Street featured Market Square and was parallel to Gay street but a block or two on the other side from Central. Pop Joffe had immigrated to New York City from his homeland, one of the Baltic countries, before WWI. I am guessing Vilna, Lithuania, sometimes referred to as the ‘Jerusalem of the North.’ Violent anti-Semitism made life unbearable there in those days. Soon after immigration he was drafted and sent right back to fight on the western front against Germany in WWI. Apprenticed as a tailor in New York, he used that skill to become a clothier in Knoxville. In his store he sold, altered and repaired suits and pants. He also sold all kinds of men’s clothing and shoes, new and used. A customer could also pawn a pair of shoes at the Dixie Store on Saturday for a weekend date, redeeming it next payday. He sometimes showed me pistols pawned and ammunition all stored in the safe, located under the main cash register. Pop was a gentle man, good in business, and with a big heart. I came to love Pop.

As with many “Russian” Jewish immigrants of his generation starting in New York, they saved their money, and migrated with their families down the Appalachians to towns like Johnson City, Knoxville and Chattanooga. Pop’s oldest son, Louis, was born in Paducah KY, one of the family’s odd stops along the way. Pop had cousins in Johnson City, and Chattanooga, some had the sir name Heller. There they opened small businesses and most of them prospered.

Central Street was a district where European immigrant merchants had storefronts easily accessible to farmers who came to town on Saturdays. It was also a favorite shopping area for African-Americans who lived in the neighborhood and in the surrounding area. A few doors away stood a fresh fruit and vegetable stand owned by Italian-Americans, the Provenzas, another store by Jewish merchants that included shoe repair (Mr. Nadler). As I recall the Provenzas lived in a big house on 4th Avenue, when we lived at the corner of Randolph Street (this corner was erased years later for a cloverleaf exit/entry onramp from the Interstate, long after I left Knoxville). There was a small sandwich shop owned by Greek immigrants, the Gorgases. A close friend of the Joffe’s named Leon Sarof owned a pawnshop on the southwest corner of Central Street and Vine Avenue. In 1959 Leon sold me an engagement and wedding ring package for my marriage to Jane. Because of family friendship he made me a good deal.

Diagonally across the intersection of Vine and Central from the pawnshop was a pharmacy, which had a platform that opened like a stage a yard or two above the sidewalk on the corner. On Saturdays a barker-vendor would sell patent medicines from this location. As a child I loved to stand in the crowd outside that store and listen to the pitch offered by that huckster on the stage. The show often opened with live snakes (somehow related to patent medicine being peddled) and live country music, then the hard pitch began. These ointments and tonics on sale could cure any ailment from sore muscles to failing male prowess. Actually, my mother did not like me hanging around there and would yank me away. Street life on Central was colorful with drunks and prostitutes roaming about.

Prompted by the recent situation in Tulsa, I found myself looking into the Knoxville riot and same in other American cities of 1919, called “Red Summer.” Of all things, the epicenter of the fighting in Knoxville was exactly at the corner of Central and Vine. (See “1919” by Jack Neely)

Glenn’s wife, Aunt Jean, worked at the (Pop’s) Dixie Store as a sales clerk all through the war while Glenn was away in the Pacific. At about age six I would sometimes visit the store and was drafted into selling new Rayon socks draped over an open-topped pasteboard box that was displayed outside the storefront similar to the fruits and veggies a couple of doors away. Customers thought I was cute with my corn-silk hair. From a very early age I learned something about business, especially the sales aspect.

By early 1944 Uncle Sam drafted Sanford into the Navy and had him sent off to Great Lakes Naval Station where he underwent basic training. At the same base he learned electronics and especially the repair and maintenance of radar systems. The course lasted a year. Radar was new and highly classified. He was about 34 years old, tall (5’11’’) and skinny (about 130lbs). He never learned to swim, but did master the art of floating (especially in salt water!). He told me that since he was older than the other guys, they let him off easy on the calisthenics during basic training.

Sanford was an intelligent man. He was valedictorian of his class of about thirty in Dandridge, Tennessee, and his mother told me once that she thought he might have had a career as a preacher. One time he told me he had read the Bible cover-to-cover twice. I believe it. But he despised the fire and brimstone preachers that were common in the time and place of my youth. He viewed himself as a gentleman and this behavior did not suit him.

Later as a teenager I never managed to beat him at checkers. I could not win, even when I was in college. I later learned that he was a champion on his light cruiser in the Pacific. He never bragged about his talents. Another thing I remember about his intelligence was that he subscribed to both Knoxville newspapers, and he worked both crosswords by the clock, rarely losing to the timer. I tried to do those crosswords, but never could get to first base.

Both of the Joffe sons were in the US Army. The older, Louie was tall, had been a basketball player at Knoxville High School. Louie served in the Aleutian Islands off the Alaskan mainland. My dad said that Louie won lots of money from his fellow soldiers in the Army, possibly a nest egg for his business investment later. His younger brother Abie was sent to the European Theater. After the war both Louie and Abie opened stores, one next door to the Dixie Store and the other around the corner on the south side of the sloping up Vine Avenue half way up the slope to Gay Street. Louie sold new clothing and dry goods and his brother sold small appliances including radios and phonographs, new and used. Abie later went back to school with the GI Bill and eventually and became a pharmacist, opening a pharmacy in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. I visited him much later when I worked at Oak Ridge. One of their age group was David Richer, whose family were fine fur merchants at a fashionable store on Gay Street. When they all came home from the war, there were poker games on a blanket spread in the yard outside the Joffe house, and I ran around pestering them.

When Mrs. Joffe died in approximately 1943, Marjorie, Aunt Jean and I moved into the house with Pop, who was very distraught with his two wonderful sons overseas and still grieving the loss of his wife. He was pretty much helpless in the house. Aunt Jean worked at the Dixie Store and Marjorie looked after me and the rather large house on McCalla Avenue. In the front window hung the familiar displays of the four men of the house who were overseas in the war. Happily, none were killed or even injured. There were different colors on the window displays around town according to which service, and injured or killed.

I still have postcards from Sanford and Glenn from faraway places. In 1945 Sanford finished his training and boarded the light cruiser, the USS Amsterdam, heading towards Honolulu and then Tokyo Bay. Luckily, just before the ship came close to its destination, the atom bombs were dropped, and the war was over. Nevertheless, the war changed both Glenn and Sanford. Both accelerated their drinking, and most of their former goals and ambitions were diminished. The naval experience had left a permanent impression on them. While it made them see a larger world, they had not sought it. In the case of Sanford I think being on a ship going across the Pacific, never knowing when that torpedo might hit, had some traumatic residuals. With Glenn It was more like the symptoms like PTSD that we hear so much of today.

I was an only child, and when I asked about having a sibling someday, Sanford always gently replied, “we cannot afford another child.” He liked to call me ‘Mac’, the nickname sailors used for one another. It was all in good humor. By the way, I never called him Sanford, but rather ‘Mac.’ He also liked to use naval terms such as the ‘deck’ for the floor and the ‘head’ for the toilet – I used them too in his presence. He referred to Englishmen as limeys. While he drank too much, he was a sedentary drinker. He never raised his voice to my mother or me, and he never touched either of us in anger. Come to think of it, he never raised his voice to anyone. My mother applied the few spankings I ever received, all below my age of about eight.

After the war Pop Joffe took me on two buying trips via rail. We slept in our upright coach seats and stayed at the YMCA Hotels at our destinations. The first trip was to Chicago where he bought wholesale goods to sell in his store — shoes, pants, work-gloves, overalls, etc. He took me to the Planetarium, the Field Museum and the Brookfield Zoo in the suburbs. We rode the elevated train, and I stood on the windy shore of Lake Michigan. The next year we went to New York City where we did similar things (Bronx Zoo, Empire State Building, etc.). In both cities he had relatives that we visited. He sometimes passed me off as his grandson – it must have been a hard sell with my light blond hair. These two trips enlarged my scope of people and places, and even at that age, I felt that I would someday leave East Tennessee for the larger world.

Sanford clearly loved me, but he was a quiet and private man. He really did not like talking much to anybody. I was always curious about his past, and especially his naval experience, but he was only available for a few minutes of discourse before he returned to reading. He did relate to me one (possibly apocryphal as to his actual participation) story when he and some of his friends in Dandridge played a terrific Halloween prank. They had a neighboring farmer curmudgeon who was not so friendly to kids. They took apart a wagon and reassembled it on his barn roof. What a sight to wake up the morning after Halloween and find your wagon atop the barn! Another prank was that they cut the wires to the school bell with wire cutters that did not break the rubber insulation. This made it nearly impossible to spot the break. It was pretty strange and chaotic when the bell did not ring for class the next morning. These stories are so ironic considering his sedentary life style as I knew him.

After the war Sanford and Glenn returned unharmed, and we moved into a trailer a block from the Joffe home. My mom rode to work with Pop where next door she worked in Louie’s new store as a clerk. My father was manager of the Western Auto store on Knoxville’s main drag, Gay Street. In a few years he left that job, I think because he hated managing people and in addition did not like meeting with customers. Basically he was friendly, talented and organized, but crippled by anxiety.

He moved to become a small appliance-repairman at Sears in North Knoxville, on Central. He fixed everything from toasters and radios to (eventually) TVs. He liked being back in the shop with his soldering iron, meters and small hand tools, only appearing occasionally to brief a customer on the job he had finished for them. Again, he was very smart. As a challenge he liked to figure out the problem with a radio or phonograph based on the client’s description, before performing any tests with his diagnostic equipment. I went into the shop from time to time since we did not live too far away from the big Sears store. He always had a Sir Walter Rayleigh cigarette stuck in his lips or one was smoldering in the ashtray. The ashtray consisted of the end of a three-inch artillery shell used in anti-aircraft fire. The souvenir had his name engraved on its side. Sanford was good at this job. Sears kept statistics on the efficiency of repairmen at their stores across the south and he was usually the leader.

Becoming a Teenager

We relocated to a one-bedroom apartment upstairs over a Drug Store that sold sodas, magazines and over-the-counter medicines, but featured no prescription pharmacy. Once an armed bandit came in the store in search of narcotics and had to be convinced that they had none. Often especially on weekends teenagers and young adult guys gathered on the wide concreted area in front of the store in the evenings. They were just beneath our window in the bedroom, in which I also slept. There was noise and an occasional fistfight, resulting in a visit from the cops.

I was a latchkey kid. That first year at our apartment I rode to and from school on a streetcar down Magnolia Avenue only a few stops from the railway viaduct, my indicator to pull the cord for ‘next stop.’ The teenage girl in the house on Randolph Street behind the drug store was employed by my mom to see to it that I was OK after school. My daily chore was to fill a two-gallon container of fuel oil from a fifty-gallon drum behind the building and haul it up the stairs to the apartment. I then had to pour the oil into the stove’s small tank and light a flame with a match to warm up the rooms, which were left cool during the day while we were out. Otherwise, I was on my own, reading, drawing, creating cartoon strips, listening to radio shows such as the Lone Ranger, The Green Hornet, etc. I was not lonely because I had plenty to do. I did not read much – reading and arithmetic were difficult for me – drawing was OK. Eventually, I did find a neighborhood friend, Joe Franklin, whose family’s apartment was in a house on Fifth Avenue. It had a back yard, behind the Fifth Avenue house, suitable for passing baseball and football. Joe’s father was a retired army man who had a barber shop just across the street on Fifth Avenue. We played lots of stickball too in that back yard. The ball was made of tightly wadded up paper, wrapped tightly with adhesive tape. The bat was an old broomstick handle.

The owners of the store beneath our apartment, the Lawhons, had just purchased it when we moved in. They were our landlords, but they also became friends. On some weekend evenings they would bring beer and enjoy sharing it and takeout food with my parents. I would listen from my bedroom to their stories and jokes. Mr. Lawhon was a UT graduate and was manager of the Knoxville Bus Terminal. I think he was the first person I had met with a college degree, other than medical doctors. My current knowledge tells me that he had bipolar disorder and suffered episodes during which he had to be hospitalized. The Lawhons were very kind and fond of me. They allowed me to read comics and magazines – with the condition that I take them from the shelf and go into the back room, so (other) freeloading customers would not see me. The only serious reading I did was ‘how to do it’ magazines on how to play baseball and football, step-by-step. I learned how to grip, throw, slide, swing, punt, etc., by following the instructions and line diagrams. This paid off in stickball.

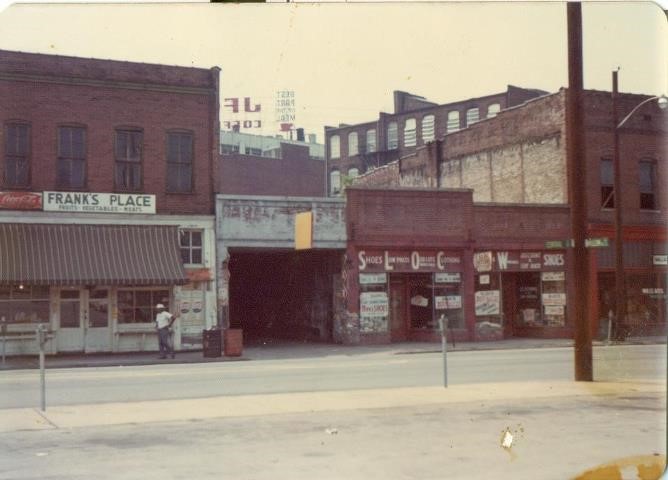

N. Central Street showing SLOC’s on the right, circa 1950s. Frank’s Place on the right was a fruit stand. The JFG Coffee sign on W. Jackson Avenue is visible in the background. (Courtesy of Gerald R. North)

In the summer I walked just about every weekday from our apartment over the drug store to the SLOC store where my mom worked on Central. She checked me out, gave me about forty cents, and I walked up to Gay Street, bought a burger at the Krystal Kitchen, and then on to the Strand Theater for a Cowboy movie (nine cents for a ticket, then up to twelve cents later). Afterwards I would stop at Abie’s store on Vine Avenue to say hello. If it were late in the afternoon, I might be concerned that I would miss one of my afternoon radio shows, and he would let me listen on one of his for-sale receivers. From there I stopped by to see mom and then on home to the apartment. Kids could not do that today.

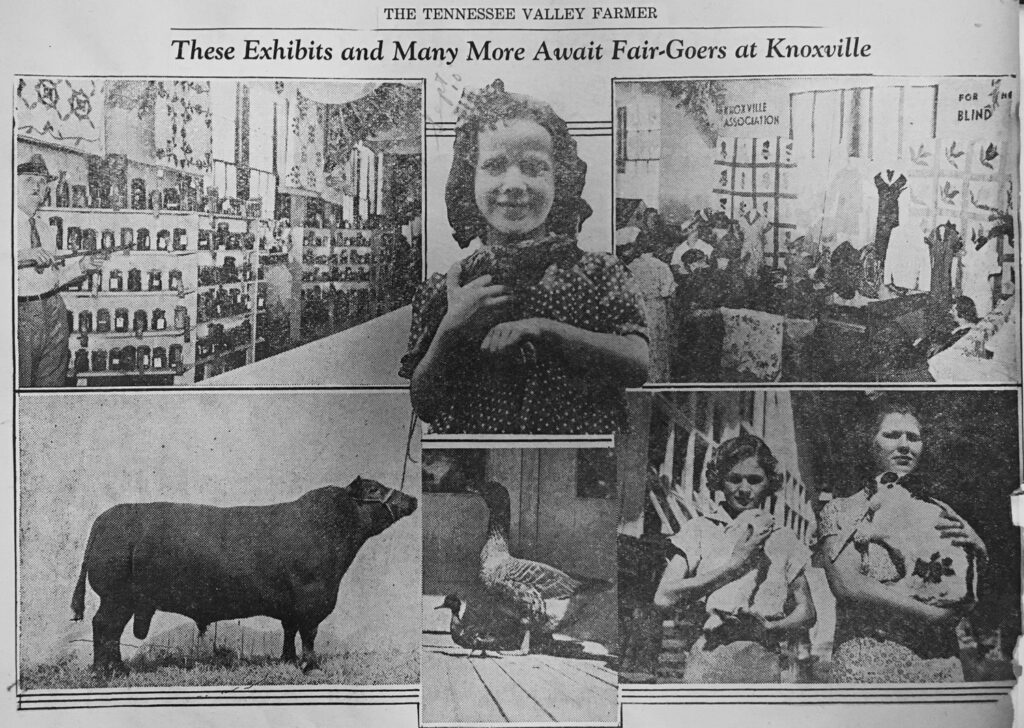

When I got to junior high, we moved to the upper floor of a two-story house (914) Gratz Street, just a block off Broadway, in North Knoxville. In a year or two we swapped with our landlord, Mrs. Vaughn, a widow who had lived in the downstairs apartment. We had a backyard where I was allowed to grow bantam chickens, Rhode Island-Reds, Polish, bantam game chickens, etc. I had lots of neighborhood friends who helped me building pens, and caring for the birds. I had a few rabbits for a short time. I think we ate them. I even showed some of my chickens in the Tennessee Valley Fair, which was held annually in Knoxville at Chilhowee Public Park. The entrance to that park was located just a block away from our former residence on McCalla Avenue during the war; so I was familiar with the neighborhood. The fair grounds were also the scene of circuses and other events. Since we lived so close in those earlier days (up to about age 9) we could simply walk over to concerts, fireworks, etc., in the park.

Chickens, cattle, and agricultural exhibits have been a longstanding activity at the Tennessee Valley Fair and remain so today (McClung Historical Collection)

Getting back to Gratz St., I led the neighborhood kids into building crystal radios – my father provided some assistance: a sketch of the wiring diagram. He told me that he built the first radio he had ever seen from parts bought from a catalog. A crystal radio (see Wikipedia for details) consisted of a coil wrapped on a heavy pasteboard tube (it took one more sturdy than the cardboard cylinder in a toilet roll), a condenser (capacitor), a crystal mounted in a lead base (about the size of a penny, only thicker like a heart burn pill). A little detector that had a sharp tipped wire was used to touch the top of the crystal (it acted like a diode in today’s parlance). Finally a pair of earphones was hooked up, and an antenna had to be strung up outside the house like a clothesline. This latter was at the consternation of my mother and the wonder of our landlady. The pieces were mounted with screws on a small (sanded and polished) block of wood, the ‘chassis’ of the instrument. The coil was adjustable in length so that you could tune the frequency of the (AM) frequency to the desired station. Imagine the excitement of the Huck-Finn-like crowd surrounding the receiver when the first station was detected! Each guy, grasping for the headphones. Of course, lots of trial and error was preliminary to the big event. Sorry for the details, but as an old science teacher, I couldn’t help it.

It was the best time for my dad and me. We lived less than a mile from Knoxville’s minor league baseball park, and he would walk with me to the games often several times a week during the season. Other times, I would walk with neighborhood kids. We were part of a club called the “Knothole Gang,” named after those who watched the game through knotholes in the outfield fence. Club members often got free or discounted tickets. The Knoxville Smokies were a Class B league farm team in the Tri-State League affiliated with the New York Giants at that time. They won the pennant that year. A couple of the players that I remember (Foster Castleman, Ron Samford, and manager Jack Aragon) and that some made it to the big league team for a few games in later years.

Although not very talented and skinny, I worked hard to play baseball and did play on a team for 12-year-olds affiliated with the Boy’s Club of Knoxville – my family could not afford the “Little League,” which required purchasing a uniform and we had no car, The Boy’s Club only required a cap and was walking distance. I was an avid sports fan, and I followed the University of Tennessee football team on the radio, but never attended a game. The newspapers showed portraits of the players, and I drew idolatrous sketches of them.

I became an avid fisherman with my Gratz Street pals. Someone always supplied transportation and we fished in all the man-made lakes in the area, including Norris, Douglas, Cherokee and Fort Loudon. In some cases we fished below the dams in water up to our waists. I can also remember fishing for carp and catfish near the mouth of First Creek into Fort Loudon Reservoir (Tennessee River). The lake was pretty nasty in those days (so was First Creek), and after hauling in one of the bottom feeders we would release them or give them away to hungry spectators. My mother did not approve of fishing there but she gave in. “Just don’t bring one of those things home!” We walked all over inner Knoxville including down Central Street to the River. I can remember smelling the JFG coffee brewing as I walked along Central Street near their building.

At age 12 through high school I worked Saturdays during the school year and full time in the summers as a clerk at one of Louie Joffe’s stores. He eventually owned three stores that catered to the same kind of working (or farming) class clientele. I learned to approach a customer, explain our merchandise, help in fitting, and complete the sale. I also lettered the cardboard signs with a wide tipped pen dipped in India ink. These stood on clip-stands over the counters or tables covered with merchandise. This was a great experience for me since the act of selling a product is a key skill often called upon in science. The pay was low, perhaps $5.00 for working all day Saturday, but my father said, I should do it even for nothing, because the skills learned were so valuable. I think he was right. He thought very highly of the Joffes. Many of the customers were African Americans (colored people, as we said then) and I developed a liking for them. Most of the others were working class whites (overalls, jeans, boots, gloves, etc.), and I was interested and sympathetic to their worlds. I was a cheerful salesman, just as today.

In one of those periods I worked in the Lonsdale store on Tennessee Avenue and (I think) Johnston Street. We stayed open on Friday nights until 9:00. Louie would join us after he closed the downtown store, and he and I would stay until the Lonsdale store closed. Afterward, he would take me out for a steak at one of the better restaurants in Knoxville. I especially liked the iceberg lettuce with Thousand Island dressing. One in particular, that I remember was Regas Restaurant on Gay Street. I recently learned that it closed after nine decades of family ownership in 2010.

One minor price I paid for working for the Joffe’s was that the neighborhood I lived in had lots of boys that I liked, but most were disgustingly anti-Semitic. I was always teased with the nickname ‘Heeby’ or ‘Abie’ throughout my ages 11 to 15. It was always a light-hearted tease, and I tried to ignore it, but it stung. These kids loved me, and vice-versa, but teasing was part of growing up. I always tried to explain what wonderful people my Jewish friends and African American customers were, but they never got it. We all used the N-word, knowing no other way, but my mom would shush me for it, and I gave it up. I never used a pejorative expression for Jewish people. Schools were segregated and my friends never had close up experience with colored people.

Most of the boys I chummed with in my Gratz St. era were children of plumbers. We had all kinds of plumbers. One of my best friends was an Irish Catholic boy, Joe Hannifin, who was an orphan son of a plumber, being raised by two old-maid aunts. He was guaranteed a membership in the plumber’s union as soon as he came of age. He was naturally a Democrat. His next older brother was already a member. The oldest of the three Hannifin brothers went to UT (Knoxville) and graduated as a mechanical engineer. I knew him because in high school he was a soda jerk in the Lawhon’s drug store above which we had lived before we moved to Gratz Street.

Across the street from us on Gratz Street were the Grissoms, also plumbers, but they were strict Methodists and non-union. I remember the radio blaring in their house when the McCarthy hearings were going on and their cheering the monster. Obviously, they were Republicans, and they hated Truman. There was another family named Lee whose dad was a plumber, and the boys –younger than I — probably became union plumbers as well. I was treated well by all of these folks, even invited to their church services, in hopes that I might be recruited, but it never happened.

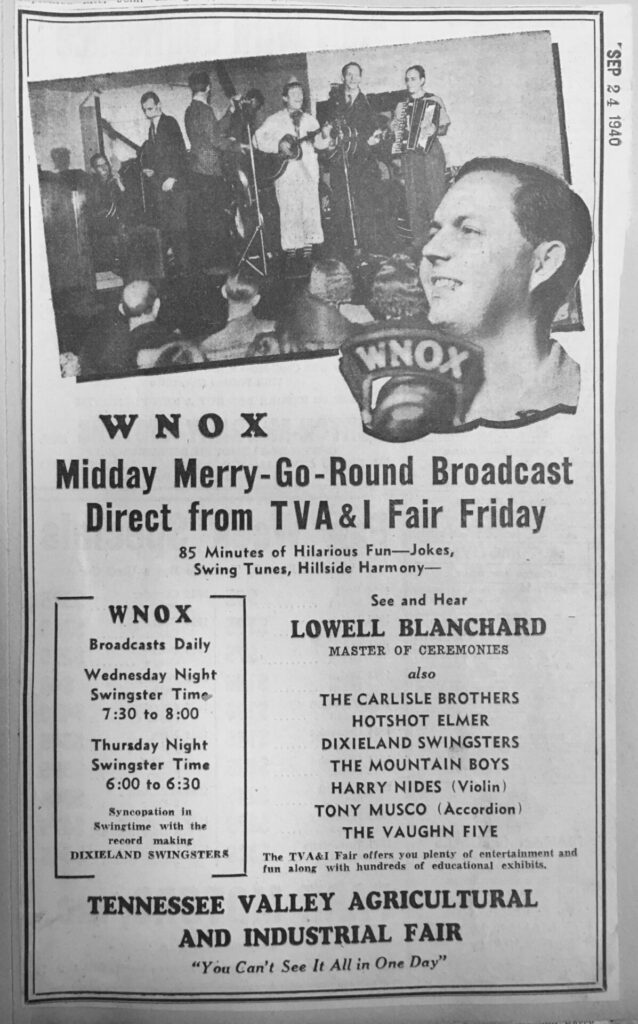

One delightful memory was a family who lived next to the McCallie schoolyard on Gratz St. where we often had pickup softball games. Red Murphy and his wife Bessie Lou, who was pregnant at the time, were performers on the “Midday Merry-Go-Round” daily and the “Tennessee Barn Dance” on Saturday nights, all hosted by a radio personality named Lowell Blanchard, who also became a city councilman. The radio shows were broadcast on WNOX. Our neighborhood friends were professionals who played hillbilly music at the auditorium in downtown Knoxville. In the show Red pulled out a large wooden mat from which he did a high speed tap dance. He usually told a joke or two for good measure and played in the band. I have tried to look them up recently, but I could not find a trace of them except for a reference to their names – I suppose they never made the big time like my baseball minor league idols.

The venue served as a kind of minor league stop for musicians moving up in country music. In my time in Knoxville later stars as the Everly Brothers (“Bye, Bye Love”) and Don Gibson (“Oh Lonesome Me”), to name a few that I saw. They got their starts in Knoxville on their way to stardom. The big league of country music of course was the ‘Grand Ole Opry’ in Nashville. We got to know these performers because Red was a singer and tap dancer, often came out to play ball with us. Bessie Lou was a fine guitarist and a sweet singer. We often got to hear them rehearse. During those years I did get to attend the ‘Grand Ole Opry’ in Nashville once when Joe Hannifin’s cousin drove us over to Nashville for an unforgettable experience. After the Opry we toured some of the record shops where the live music went on until the wee hours. I still remember the sadness from Hank Williams’s death in 1953 that I think occurred near Knoxville. I still love Blue Grass, and I went back stage to greet Flatt and Scruggs when they had a show in Madison, Wisconsin in the 1960s.

Returning to my family, my parents had been reared in Baptist churches. My father grew up on his father Jerome’s farm in Dandridge. Jerome eventually owned a small coal yard. Later, as I was growing up, he was a life-insurance salesman in Knoxville. He died when I was about nine years old of a heart attack in his mid-sixties. Sanford’s side of the family was a solid lower middle class and church-going family.

Based upon her fears of losing my father and her brothers in the war, my mother was overly protective of me. She dressed me and doted on me relentlessly in early childhood. Every shirt, pants, sock and underwear were washed in the tub with a washboard, and all were ironed. She ironed the sheets and pillow cases. In the early days she used a cast-iron iron, heated on the stove. I was considered to be a sweet little boy, but as an only child with dad away I also grew rather manipulative. I was a skinny, picky eater, afraid of heights, snakes, bugs and water. Water was especially worrisome for my mother because of the polio epidemic that was rampant in the Forties. One little boy in my second grade class died from it.

She dressed me up and sent me to Sunday school, and in summers to Vacation Bible School. I participated, and by age 12, she sent me to the huge Broadway Baptist Church a few blocks from our house on Gratz Street. My Sunday-school teacher was always pressuring me to be saved, which meant emersion. The Baptisms took place in a well-lighted indoor tank with a glass wall clearly visible to the congregation, consisting of hundreds if not thousands of live viewers. I was frightened by that ritual and still cannot swim. I went to Methodist, Presbyterian and Catholic services as guests of my friends – those only required sprinkling for admission to Heaven. None seemed to work for me. I never got baptized and even at that age, had begun to think that the whole organized religion thing was not for me. Somehow there was too much argument over the minutiae of the Bible. My mother never pressured me after that. I think she was baptized in the ice-cold Little Tennessee River in Calderwood, Tennessee. I attended a funeral in Calderwood once when I was about eight. The fire and brimstone preacher scared the Hell out of me. But actually my Marjorie never attended church herself until she became a widow. At that time the bonding with church friends was very comforting for her. My father had no interest in churches. For reasons that I never knew, he was estranged from his family, and mocked at the hypocrisies (real or not) of southern church members. He never tried to tell me what to do about religion: “That’s your business”.

High School Days

In about 1952 my parents bought a small two-bedroom house for $6500 at the corner of (433) Columbia Avenue and Harvey Street in North Knoxville a year after I started in tenth grade at Fulton High School (FHS). FHS was only a year old. It was the city’s only combination of trade school and regular liberal arts school. Some kids opted for the trade school curriculum that included auto mechanics, print shop with linotypes, sheet metal, etc. The girls could choose cosmetology, secretarial, etc. My first homeroom was in the sheet metal shop.

My father met one of my (Park) junior high teachers, Mr. Monday, who happened to be a customer at the Sears repair shop. I was in both of Mr. Monday’s machine shop and mathematics classes. My father was not only very smart but also good with his hands in a shop – I still have a bookcase beautifully wrought of heavy oak that he built in his high school shop. Mr. Monday told him I was pretty weak in the shop, but actually very good in math – by then I had overcome some of my arithmetical shortcomings (which I attribute to a wicked fourth grade teacher). My father thought I should be a medical doctor. So I signed up for Latin rather than math in my ninth-grade year. He figured doctors do not need much math, except in the investment choices for their “bloated” incomes, but Latin might be good for writing prescriptions and naming bones. He had also taken Latin, possibly four years of it.

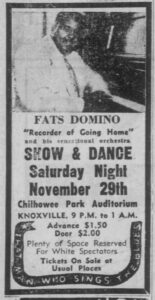

I ran with a marginally rough crowd in high school. I was still too skinny for any high school sport, but I could draw caricatures and act silly – in fact, I developed into a class clown. I also had blond, slicked back, wavy hair, and I wore cool clothes like pegged cuffs on the pant legs – a bit like Elvis, but I hated him. I preferred rhythm & blues or jazz. I was an early fan of the sounds of colored musicians. I even attended R&B concerts where I saw live performances of the likes of Fats Domino at the auditorium at Chilhowee Park. I tasted no alcoholic beverage until perhaps late junior year, when I drank beer with my pals. No descent girl would drink a beer. It was long before the appearance of pot in Tennessee, and sex with nice girls did not happen. I went to proms, social club parties, etc. I did not study very much, accepting the gentleman’s Bs and Cs. In senior year, I buckled down a bit, especially physics and geometry. I cannot remember reading a single book in high school, except maybe a Mickey Spillane hard-boiled detective (Mike Hammer) story that included some racy action.

During the beginning of my senior year our new high school physics teacher was delayed from appearing in town for the first few weeks. I was astonished to learn that the school would ask me to ‘teach’ the physics class until he arrived in a few weeks. I had such a grip on chemistry the year before (even though I was a terrible cut-up and prankster) that they thought I might be able to do it. Frankly, I did only so-so at it. But this and my good performance in the geometry class were probably indicators of my future course.

Of the 300 or so in the graduating class, maybe a quarter started college. I might have been in the top quarter, but barely. This change of education level called for a reset: I cut off the long hair and became a square. I followed the path I learned as a responsible store clerk from my beloved Jewish mentors in the retail clothing business. Later when I worked at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, Louie sent his youngest son Paul to study there as an undergraduate, so I had an opportunity to at least in some sense return the favor. The favor I took from Louie was the self-discipline in work and later in study. When I got sloppy arranging or labeling merchandise, he would come over and say firmly “a job worth doing is a job worth doing right.” The favor his father, Pop, did for me was to enlarge my horizons so that someday I would think on a larger scale, to be at home in Chicago or New York, or wherever I might land someday.

I had a few dates in high school but was pretty shy and hardly attractive. In the spring of my senior year I met Jane on a blind date when a friend, Jim Corcoran, wanted to date a beautiful girl who was friends with Jane Enneis. We went to the Great Smoky Mountains for a Sunday outing, wading creeks, etc.

Jane was a year behind me and from an upper middle-class family across town. She had many friends in the old southern upper class. In fact, I was her date for her “coming out” dance. It occurred on Chattanooga’s Lookout Mountain at a big event called “The Cotton Ball.” We rode to Chattanooga with some of her friends, and I had to wear a white dinner jacket, etc. For me it was a wretched experience, but she was able to overlook it, and keep me around. We were married three years later in 1959 and we took our honeymoon by driving up to Chicago where I took her to all the spots I so enjoyed as a child with Pop. In our second summer we drove to New York, watched some shows — I remember “Gypsy” with Ethel Merman. From there we drove on up into New England, passing through Vermont, New Hampshire, stopping in Boston and the rocky Maine Coast. By that time, I was sampling different places for graduate school.

If you should wonder what happened to me, you can read my book of Memoirs and learn about climate science while you are at it.

The Rise of Climate Science, a Memoir by Gerald R. North

This essay has been modified from a memoir named above and scheduled to be released on October 15, 2020, by Texas A&M University Press. The book tells how the author moves from his childhood home Knoxville to many venues before he settles at Texas A&M University as a Climate Scientist.

This essay has been modified from a memoir named above and scheduled to be released on October 15, 2020, by Texas A&M University Press. The book tells how the author moves from his childhood home Knoxville to many venues before he settles at Texas A&M University as a Climate Scientist.

Contact Gerald North, University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Research Scientist, W. J. Haynes Chair (Inaugural holder) at:

https://atmo.tamu.edu/people/profiles/emeritus-faculty/northgerald.html

I took the snapshot on the cover at a huge glacier in Uzbekistan.

https://www.tamupress.com/book/9781623498672/the-rise-of-climate-science/

or email Gerald at g-north@tamu.edu

Available at:

https://www.bookdepository.com/Rise-Climate-Science-Gerald-R-North/9781623498672

or

https://www.amazon.com/Rise-Climate-Science-ConservationEnvironment/dp/1623498678

###